Capital and Culture: Musil's Politics

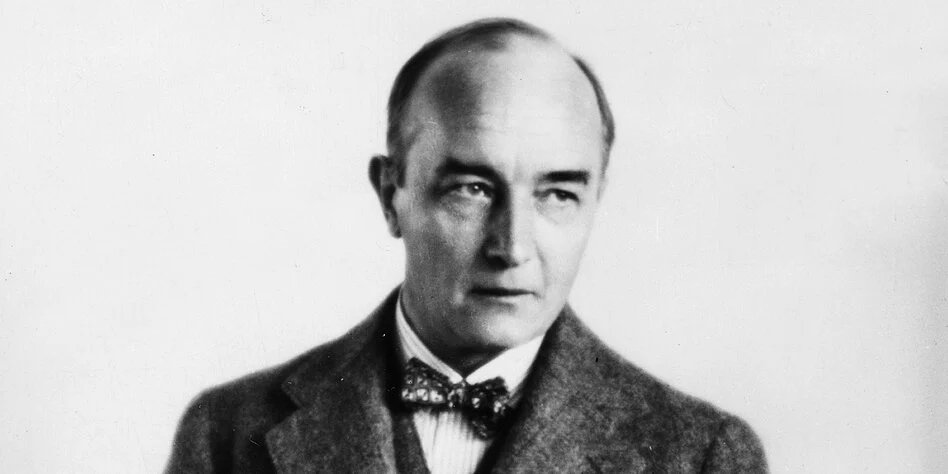

Robert Musil was one of the great novelists of twentieth-century Europe. A recently translated collection of his essays, Literature and Politics, Drew Dickerson argues, can help us see more clearly the historical and political context of his masterpiece, The Man without Qualities.

At the age of fifty-six, Robert Musil was already writing of his career in valedictory terms. That year he published the short prose collection Posthumous Papers of a Living Author in Zurich. It was that same year that Musil suffered his first stroke. If the author felt he was scrambling to publish against borrowed time, this was more than presumption. Historical circumstances, too, had conspired to wrongfoot his literary reputation and livelihood. The extant volumes of Musil’s masterpiece, The Man without Qualities, appeared in 1930 and 1932 – hardly time for the reading public to absorb their impact before he and his wife Martha were forced to flee first Berlin and then Austria, following the Anschluß. In 1942, he died destitute in Swiss exile, working until his last day to bring one of the twentieth century’s most mysterious novels to a satisfactory conclusion.

In doing so, Musil was always aware that he wrote for a posthumous reception. Corresponding with his patron Robert Lejeune, Musil wrote that “having to wait until one’s death to be allowed to live is really quite an ontological feat.” As a gnomic expression, it’s one worthy of Musil’s fiction. At its most speculative, The Man without Qualities often reaches a similar, existentially inflected pitch. Here ontological specimens abound: a man without qualities consists just as easily of qualities without a man; a racehorse is said to be in possession of genius; das Seinesgleichen – that state of monotonous simulation which Sophie Wilkins and Burton Pike translate as “pseudoreality” – holds sway. Musil’s drafts and withdrawn galleys for the book’s ultimately incomplete third volume hew towards an especially numinous register, reading at points like a mystic’s visionary wisdom: “moonbeams by sunlight” representing fragile thoughts to be sure, the fruit of a long novel of ideas. Here late style emerges at the end of a literary project to exist without qualities, Musil’s decades-long program of rigorous abstraction, by means of which he aimed to construct that untimely aesthetic dimension in which he could wait until death to be allowed to live.

***

The narrative occasion for even The Man without Qualities’ more episodic chapters is beset by equally thorny conceptual arrangements – and the motor of the novel itself often lies in devising technical workarounds for contents that are not particularly given to novelistic treatment. In a chapter that the reader is wryly invited to skip, the book’s narrator invokes the difficulty of writing about thought, before proceeding to do exactly that for the remainder of the thousand some-odd pages that were published in Musil’s lifetime. Ulrich (the eponymous main character, his last name suppressed out of consideration for his jurist father’s respectable social standing), finds himself – after an early adulthood of fruitless attempts to derive significance from one career after another – more or less accidentally attached to preparations for a jubilee honoring the seventieth anniversary of Emperor Franz Josef I’s ascension to the throne of Austria-Hungary, called the Parallel Campaign, due to the fact that celebrations of Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm are to take place in the same year.

The setting is Kakania, a country entirely coincident with the geographic borders of the Habsburg Empire, different only for being fictional. The name is Musil’s own coinage, its puerile kaka connoting the label kaiserlich-königlich (Imperial-Royal) of the Dual Monarchy which united the capital cities of Vienna and Budapest until the state’s dissolution after the First World War. Ulrich’s role is attaché for the campaign’s originator Count Leinsdorf, a noble functionary whose old-fashioned orientation allows him an uncritical faith in the spontaneous accord of “capital and culture,” watchwords to which he finds nearly constant recourse. In salon conversations and calls for proposals, the committee entertains alternately insipid and extreme ideas for the celebration, in search of an inspiring symbol that would serve for the nations of Europe “both as a warning and as a sign to return to the fold… and all of this connected with the possession of an eighty-eight-year-old Emperor of Peace.”

Just as the Parallel Campaign affords Musil opportunity to detail the many ideologies vying for dominance in his prewar Kakania – among them pacifism, bellicose nationalism, the aesthetics of personal cultivation, and vegetarianism – so too does it allow him to stage the problem of ideology as such. The principal action of The Man without Qualities’ first volume is taken up with Ulrich’s compatriots trying and failing to hit upon an integrative idea adequate to comprehend and express the contradictions of an empire containing 52 million subjects, fourteen officially recognized languages, an unsettled antagonism between industrial and semi-feudal elements, and no common model of citizenship between its nationalities.

It is campaign member General Stumm von Bordwehr, a bumbling career soldier and butt of much of the novel’s comedy, who is most concerned to make sense of the cultural situation’s disarray. He compiles a report of contemporary thought for his superiors, ending with a document of several dozen pages written in strategic terms: battalions of ideas, intellectual matériel, shifting positions, circles, squares, crosshatched areas.

“The better we understand things in detail, the less we understand the whole, as it were,” Ulrich quips, “so what we get is a great many systems of order and much less order over all”. Indeed, if the ethic of systematizing order which becomes self-conscious in Stumm’s battle map can be said to have advanced European understanding of many particulars, the dispersal and departmentalization which is this understanding’s condition disqualifies it from any comprehension of the whole. In the face of this problem, Vienna’s elite seem content to trade merely verbal solutions. Musil’s artistry is to make reason misfire in its attempt to give account of itself.

As Stumm von Bordwehr’s responds, “But don’t you think all this confusion seems to justify the military position – though I’d be mortified to have to believe it even for a minute!”

***

In The Man without Qualities, the First World War features as a vanishing point. Never arriving, it nevertheless informs the choice and placement of every least detail. As one of Musil’s working documents for the novel’s unrealized conclusion has it, the answer to the question of what will develop from this setup is simply “… nothing or the beginning of the World War.”

Musil’s own war was spent first at the front (diary entries include a literary sketch of being under bombardment) before his promotion and transfer to Austria’s Supreme Army Command in Bolzano. With his protagonist Ulrich, the author of The Man without Qualities then shared an officer’s career of some distinction. The experience of mass mobilization would be decisive for Musil too who, with his 1908 doctoral thesis on the positivist psychology of Ernst Mach, had already come to understand the psychic substance as essentially malleable. Add to this the historical disappearance of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a territorial entity and form of life following the war, and it’s easy to understand why, by his 1923 essay “The German as Symptom,” Musil had come to characterize his philosophical anthropology in terms of a “theorem of human formlessness” by which the mass of humanity is understood as something irreducibly liquid, lent form only through adherence to this or that chance code. Society, discipline, and the plasticity of the individual ego would accordingly number among Musil’s themes.

Deciding in the summer of 1913 to take a leave of absence from his life, Ulrich occupies himself by examining every available reality and possibility with an empiricist’s detachment. Value systems are considered and abandoned. Questions of utopia are entertained, as are penetrating characterizations of the everyday. In Ulrich, we see an attempt to make of formlessness a positive artistic affordance – as he seeks through means of precision and soul to devise for himself the right life, and this from the middle of all the Parallel Campaign’s noisy make-work.

By a trick of historical forced perspective, the reader knows that both of these personal and political efforts will shortly come to ruin in the malfunction of Europe’s precarious balance of international powers. For the novel, the war is an absent cause.

***

A great deal of the pleasure of Musil’s fiction comes from his representation of Habsburg Austrian society – a clamorous order rendered with deftness and humor in the moment just before the state’s disappearance. Yet, it remains a source of generative tension that this specific, periodizing interest of The Man Without Qualities should share so much space with Musil’s unbounded conceptual leaps into a more lyrical, sempiternal dimension. Indeed, Ulrich’s leisured contemplation of right living is undertaken from the artificial safety of the thinly fictive Kakania, a country from which the real-world menace of the First World War remains constantly deferred. There is a contradiction here between the sturdy facts of history and Musil’s faith in a timeless utopian element which would be something like this conjunctural past’s meaning. In this lies the significance of Ulrich’s “scheme for living the history of ideas instead of the history of the world.”

The elaboration of these two terms is central to the development of Musil’s thought: reality and possibility, precision and soul, determination and indeterminacy are all submitted to the appraisal of his formal intelligence. Throughout his published output as well as the Nachlass, Musil remains first of all interested in a clear-sighted account of present circumstances (he was “monsieur le vivisectuer” as early as his schoolboy journals) alongside a rigorous attendance to these same circumstance’s progressive potential. The project of mystical transfiguration, pursued in such a fashion, is made to satisfy the requirements of an absolute objectivity.

***

Literature and Politics: Selected Writings, a new collection of Musil’s work published in March by Contra Mundum Press and the final book in a four-volume Musil translation project from Genese Grill, reproduces a number of drafts and public speeches from the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 onwards. Faced with world historical catastrophe for the second time in his adulthood, these years would be ones in which reality and the role of the writer in shaping it ceased to be abstract. The rightwing seizure of German-language literary society left Musil penurious and reliant on intermittent patronage, and they all but forced him from his home country.

The problems of the period throw his literary work into high relief. Before the thirties, Musil’s politics were something like that of a committed leftist, even if he consistently refused identification, concerned always to maintain his stance as a non-conscripted intellectual. In 1918 he was a signatory to the manifesto of the Political Council for Cultural Workers (the group’s demands included the socialization of land and transformation of capitalist firms into worker cooperatives), and in correspondence with a Moscow literary journal he expressed admiration for the Bolshevik revolution and he wrote of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party in favorable terms throughout the interwar years.

Literature and Politics is a testament to how totally the instrumentalization of intellectual and artistic life would come to inform Musil’s circumstances. A sketch on “the culture of political culture” bemoans the doctrinaire espousal of Catholic and Fatherland Front affiliation into which Austrian artistic production had descended; Musil’s intransigence would win him little favor with the state’s official cultural bureaucracy. Nor did his 1935 address at the USSR-sponsored International Writers’ Congress for the Defense of Culture in Paris proceed exactly as members of the audience expect. Asked to respond to the conference’s organizing theme, Musil instead offered a stubbornly precise definition of terms, beginning from the fact that “culture is not bound to any political form. Each form provides culture with its own particular sorts of patronage and obstacles.” Of the 250 writers present, André Breton was the only to join in this attitude of principled non-alignment.

None of which is to say that Musil was politically indifferent. Throughout his life he kept well-informed of current events (often reworking it brilliantly into material for his fiction), and he consistently expressed the view that capitalism was incompatible with any spiritual or intellectual development worthy of the name.

What the writing collected in Literature and Politics represents above all then is Musil’s attempt to live out the acute conflict he felt between his times’ necessity and the timelessness he accorded to the supra-national project of world culture. As an aphorism composed just before he fled Germany runs: “Ethics. My ethics has – although I like to overlook this – a ‘highest good.’ It is spirit. But how is this different from the philosophers’ idea, which is less pleasing to me, that reason is the highest good?” Clarifying the question, Musil betrays his radical aestheticism; it takes an artist to confer seriousness on the idea that a highest good should be pleasing. Meanwhile, in consideration of spirit (Geist) as this highest good, the sense of Musil’s concern to distinguish culture from any determinate political form becomes apparent: for his purposes, it is the role of politics to secure better or worse conditions for culture’s survival. Are a society’s modes of patronage and obstacles more or less propitious for spiritual development? In the case of the writer, the decisive question becomes one of which milieu is most favorable to literature – and its sometimes-subversive ends.

Everything in the collection has the effect of making The Man without Qualities’ blank spots feel all the more obdurate. If the legibility of real historical interruption is enhanced by Musil’s conjunctural writing, the novel’s conceptual aporias are underscored equally. The Man Without Qualities is unique in its solicitation and then refusal of synthesis. No denouement is forthcoming for these adventures in thought. So fastidious are Musil’s reworkings of drafts that it’s not at all clear his project could be realized on its own terms. Among literary modernists, Musil most craftily retains the prerogative to be stubborn, and questions of his work’s ultimate optimism or pessimism are left in suspense. The Man Without Qualities is then continually provocative. Massively unmanageable, its technical accomplishment is to tarry forever with questions of insoluble difficulty – this, along with the book’s fragmentation and final irresolution, testify to the fact that the success of any utopian project is far from assured in advance.