5 Book Plan: Oceans and Capitalism

Liam Campling and Alejandro Colás, authors of the book Capitalism and the Sea, pick 5 books for understanding the politics of the world's oceans.

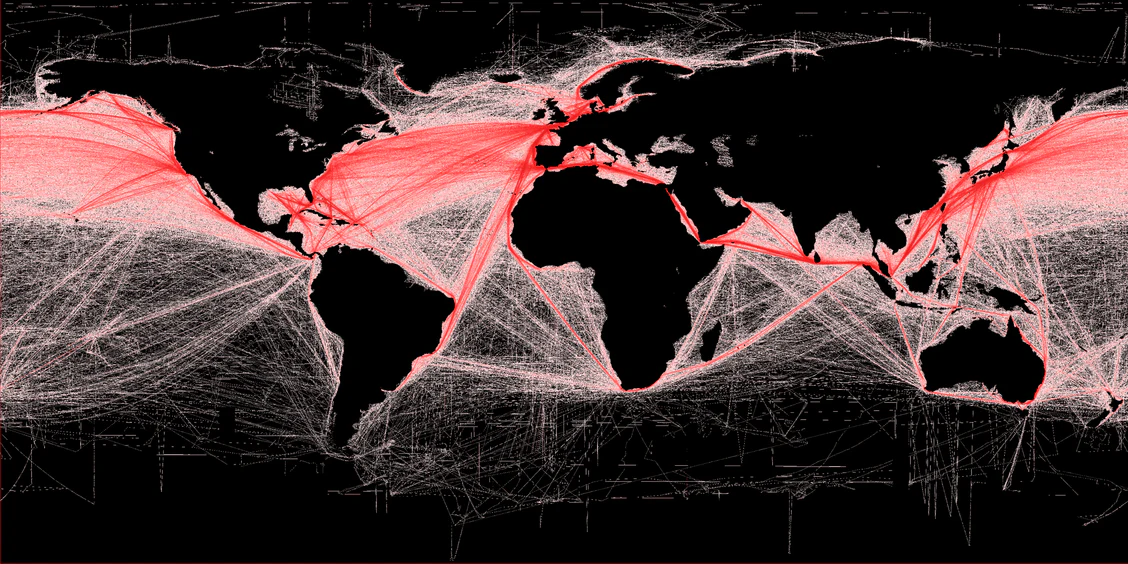

In their book Capitalism and the Sea, authors Liam Campling and Alejandro Colás analyse the ocean that has through the centuries served as a trade route, strategic space, fish bank and supply chain for the modern capitalist economy. In successive chapters dealing with the political economy, ecology and geopolitics of the sea, the authors argue that the earth’s geographical separation into land and sea has significant consequences for capitalist development. The distinctive features of this mode of production continuously seek to transcend the land-sea binary in an incessant quest for profit, engendering new alignments of sovereignty, exploitation and appropriation in the capture and coding of maritime spaces and resources.

Here they give us their 5 book plan for understanding the world's oceans.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]Covering seven tenths of the Earth’s surface, the global ocean has absorbed over 90 percent of the excess heating and around 30 per cent of the surfeit carbon released into the atmosphere since the industrial revolution. As we argue in our book Capitalism and the Sea (Verso, 2021), saving the Earth from global heating and other pathologies of fossil capitalism requires thinking terraqueously about our planet – factoring in the complex interconnections between land and sea. These interactions are certainly environmental, but they are rooted in socio-economic practices and political structures that make the land-sea dialectic central to the reproduction of global capitalism.

Eelco J. Rohling’s The Oceans: A Deep History (Princeton, 2017) introduces the centrality of the global ocean to the Earth system, pulling together an impressive range of scientific research on sea level, climate, and greenhouse gas emissions. Rohling is a paleoceanographer (the study of the ancient and ever-changing oceans over geological time) and in this book turns his hand to providing a general overview of his entire field – a 4.4 billion year history. He uses this deep geological perspective to contextualise the unprecedented speed with which fossil capitalism is warming the oceans and has committed the planet to a process of mass extinction. He makes clear that there is nothing in nature that can realistically ‘offset’ the net carbon emissions of the ‘human supervolcano’; indeed, it will take nature at least tens of thousands of years to absorb. Ocean acidification – climate change’s evil twin – will devastate oceanic ecosystems and human food systems, especially in the global South; and sea-level rise as a result of global warming is ‘virtually impossible to reverse’, and ‘will continue to rise, and will rise ever faster now that the ice sheets have started to respond to climate change’. Even assuming that we can fix atmospheric CO2 values to between 400 and 600ppm, which is optimistic given that in 2020 the level was 412.5ppm, Rohling draws on the paleoceanographic record to estimate 10 to 35 metres of sea-level rise over the coming several centuries, ‘as the full range of slow and inexorable responses and feedbacks that has now been activated plays out’.

Laleh Khalili’s Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula (Verso, 2020) is an engrossing and vivid account of the ways oil deposited under the Earth’s subsoil is – together with other commodities – shipped across the oceans to fuel the global economy. Part political travelogue, part archival history, Khalili’s book masterfully narrates how British, and later American imperial power and their local allies reshaped the political economy as well as the economic geography of the Gulf region by dotting its littoral with new ports, harbours and tank terminals in the course of the 20th century. Khalili is especially attentive to the monumental transport infrastructure and its accompanying labour power that connects inland hydrocarbons to their maritime destinations. A wonderfully evocative example of how land and sea literally meet in the construction of the eponymous sinews of war and trade involves the dredging of coastal sands, often through complex processes of land-reclamation, to be mixed as cement in the construction of roads, quays, buildings and other coastal infrastructure along the Arabian Peninsula. Such illuminating vignettes demonstrate how the seemingly mundane role of sea sand in helping to extract petroleum from under desert sands in fact lies at the heart of the current crisis of our carbon civilization.

Sunil Amrith, Unruly Waters: How Rains, Rivers, Coasts, and Seas Have Shaped Asia's History (Basic Books, 2018). The history of Arabian ports like Jiddah, Aden or Muscat and all the seaborne traffic they have witnessed is unthinkable without the Indian Ocean. Sunil Amrith’s environmental history of water in South Asia over the past two hundred years rightly emphasises the hydrological interaction between the ‘deep time’ of ocean-formation, the currently changing weather patterns around the Indian Ocean resulting from global heating, and a future characterised by the polarisation of wet and dry regions caused by Himalayan ice-melt. The Indian Ocean Monsoon (derived from mawsim, Arabic for ‘season’) has for millions of years defined South Asian weather patterns, as part of a wider planetary El Niño/Southern Oscillation. Amrith underscores the terraqueous character of the phenomenon when reminding us that it is the ‘thermal contrast between the land and the ocean, and the availability of moisture’ that drives monsoons and determines their socio-natural effects. Across ‘Monsoon Asia’ peasants and sailors, rural farmers and urban dwellers have through the centuries learned to read the skies in anticipation of either much-needed wind and rainfall, or catastrophic typhoons and flooding (sometimes all of the above). Clouds don’t lie, and Amrith’s richly-layered chronicle of the centrality of water in all its other forms – salt, fresh, ice – for the lives of billions across Asia is essential reading for those seeking to address the social and political consequences of a planet on fire.

Jatin Dua, Captured at Sea: Piracy and Protection in the Indian Ocean (University of California Press, 2019). Continuing with the focus on the Indian Ocean, Jatin Dua’s multi-sited ethnography of piracy and protection in that part of the world shows that practices of maritime predation and their counter-measures are never just about crime and punishment. In a thickly descriptive yet fast-paced narrative, Dua contextualises the shift from piracy off the coast of Somalia at the start of this century from ‘coast guarding’ of foreign trawlers fishing illegally in Somali waters to ‘private investment’ in ransoming as a reflection of, among other factors, the interplay between inland pastoralism and sea-facing fisheries, and the recharging of mainly land-based traditions of protected escort (abaan) in the shape of contemporary piracy. The peculiar properties of the land-sea relation reappear here in the seasonality of Monsoon weather patterns affecting the scale and rhythm of piratical attacks, but also in the role of distant land-side actors like City of London insurers, or EU counter-piracy taskforces headquartered in English suburbs, in the reproduction of transnational relations of trade, plunder and protection. Of the many rich insights offered by Jatin Dua’s seminal study, one of the most important is the fact that environmental change on a planetary scale always affects lives and livelihoods in different and unequal ways at the local level.

Brian Wood, Garry Brown, et al., The Massive (Dark Horse, 2019). This is a truly terraqueous post-apocalyptic vision of a world underwater. Originally published across 24 comics in 2012-14 and now collected in two ‘omnibus’ graphic novels, The Massive tells a story of marine environmental activists who survive a human-driven ecological collapse and global sea-level rise called The Crash. Living at sea aboard the ship Kapital, the protagonists struggle with their pasts, each other and what’s left of civilisation, while searching the global ocean for their sister ship, The Massive. This broken world provides a tableau for exploring post-Crash social organisation, economies, and ways of being.