Myths of the October Revolution: An Interview with Alexander Rabinowitch

"We have an awful lot more to learn about the Russian Revolution."

This is the transcript of an interview conducted on Nov. 7, 2017 by Alex Steinberg with Dr. Alexander Rabinowitch. The interview aired on WBAI radio in New York on Nov 16, 2017 as part of a two-hour special broadcast devoted to the October Revolution. It was first published at Permanent Revolution.

Alex Steinberg: In our next segment we go to an interview I conducted with Dr. Alexander Rabinowitch, Professor Emeritus from Indiana University where he taught from 1968 to 1999. Since 2013 Dr. Rabinowitch has been affiliated research scholar with the St. Petersburg Institute of History, Russian Academy of Sciences. He is recognized internationally as the leading expert on the Russian revolution. His three books on the subject, Prelude to Revolution, The Bolsheviks Come to Power, and The Bolsheviks in Power, are considered by many to be the definitive historical account of the Russian Revolution as it emerged in the key city of Petrograd. Dr. Rabinowitch remains very active, traveling to conferences all over the world and is currently working on another book chronicling the civil war years in Petrograd.

Dr. Rabinowitch it is great to have you with us. To start off before getting to our main topic I would just like to ask you how you became interested in the Russian Revolution and what motivated you to devote your entire professional career to its study.

Alexander Rabinowitch: Sure. My mother and father were Russian. My mother was from Ukraine which was part of Russia when she was born. My dad was from St. Petersburg. They both fled Russia in 1918 during the Red Terror. My dad was then a second-year student at St. Petersburg University, second or third year student. He was Eugene Rabinowitch, quite a famous biochemist but also co-founding editor of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. He had been on the Manhattan Project, was very disturbed by the building of the bomb and the implications of the bomb and founded that journal which is still going strong today. He was also a co-founder with Bertrand Russell of the Pugwash conferences of Soviet and American scientists and scientists from other countries also concerned with problems related to the implications of science in the modern world and the potential of science. My dad got his PhD in Berlin and ended up in London where I was born and we moved before the war. My dad got a job at MIT in Boston Massachusetts and I grew up in a Russian immigrant community surrounded by people who had fled the revolution. There people like Alexander Kerensky who I knew, who was the Prime Minister of Russia for much of the Provisional Government period. Vladimir Nabokov, the writer, several leading Mensheviks etc.

You knew them personally?

Yes. I was fairly young then, but people like Boris Nikolaevsky, who was sort of the archivist of the Social Democrats, was a kind of grandfather to me. He lived in our barn in our summer home in Vermont for years and wrote many of his works there. Irakli Tsereteli, the leading Georgian Menshevik, I remember well. I interviewed Kerensky a couple of times after I got serious about the Revolution. But anyway, I grew up hostile to everything about the revolution. But what sort of transformed me — didn't make me a Marxist, but changed my views on the revolution — was work with Leopold Haimson at the University of Chicago. He was a wonderful teacher and I became seriously interested in the Russian Revolution and as soon as I started working in the sources — and in the newspaper — I very, very quickly changed my views. It was clear to me that the people I had known as a kid and my parents had been forced to leave Russia — understandably, they had been the losers in the struggle for power in 1917 — but what came out in the sources was that what had happened in 1917 in Petrograd was a fundamental social and political revolution that fascinated me. That's how I became interested in the subject professionally. Haimson certainly was a very thoughtful social historian, probably on the left but not — I don't think — a Marxist. In any case he was an inspirational teacher and with his help I became fascinated by the subject. And then I was hooked by the material I was finding in libraries and archives and I went to the Soviet Union in 1963-64 and spent the year there working on the July uprising of 1917, mostly in libraries because the archives were closed to Western scholars. More and more I got fascinated by the subject and turned on by putting together bits and pieces and realizing that I couldn't do a photographic picture — that any picture that I did or any historian does is shaped by his background and his or her own views — but I loved trying to come as close as I possibly could to what actually happened.

Well you have pretty much devoted your entire professional career to the study of the Russian Revolution and kind of in a microcosm you focus on what happened in Petrograd and there basically only for a period of about a year and a half or so from the July days which was July 1917 on the old calendar till about November 1918 when the first anniversary of the revolution occurred. You broke some new ground by going through original documents to trace in detail the real dynamics of the relationship between the Bolsheviks led by Lenin and the working class and soldiers of Petrograd. In the course of your work you definitively debunked a number of myths about the October Revolution and I'd like to ask you to explain what some of those myths are and how your book debunks them. For instance, there's the myth that the October Revolution was a coup engineered by a tiny group of zealots unconnected to the masses and the associated myth that the masses in turn genuinely wanted the "democratic liberal" regime that was supposedly represented by the Provisional Government. Just this weekend The Wall Street Journal had an article with more or less this theme about the coup of 1917 and the zealots that led it and so on. Can you explain how your books debunk that myth and what you actually found to be the case?

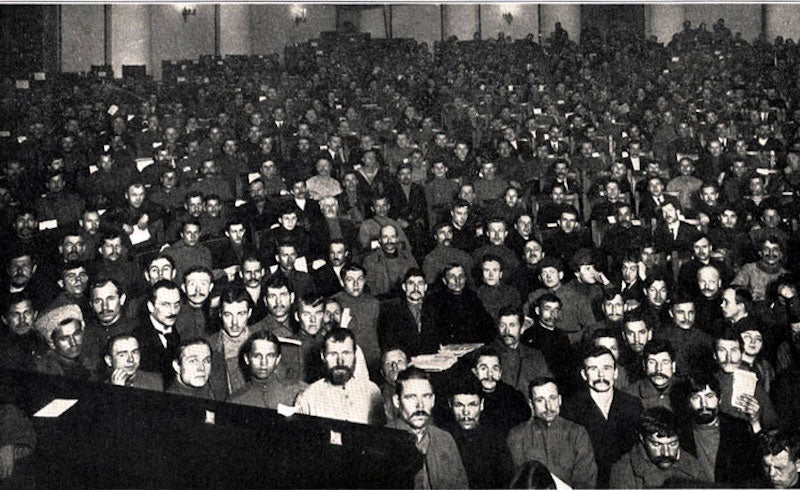

Well first of all I found that what was taking place was from February on was a major social and political upheaval that was very difficult to stop in midstream. I found that far from being the small band of “conspiratorial followers by the numbers” of Lenin in seizing power, from February on the Bolsheviks tried to develop a mass party. They grew enormously among workers and soldiers. They made a great effort to build connections with factory committees in factories and in trade unions getting strength and among garrison troops. More than any other party they were concerned with building roots among the masses and they helped shape mass views but they also were shaped by mass views. The party and in 1917 — far from being a centralized troop movement that — I think it's Applebaum — describes in the Wall Street Journal, they became a mass party and a decentralized party with relatively democratic decision-making and this was terribly important in their success. It almost was catastrophic in July 1917 during the abortive July uprising when the left-wing of the party tried to overthrow the Provisional Government and transfer power to the Soviets too early. My sense was that Lenin was opposed to that and that was part of the price of having a decentralized party. But in the long run that internal democracy and that decentralization was critical to the party's success. On two or three occasions in July, in September and October, Lenin issued orders to overthrow the Provisional Government which leaders on the spot turned down because they could see that it was very risky and probably doomed to failure with Trotsky helping lead and Lenin giving general directions from his hiding place in Finland they developed a strategy that ultimately led to their coming to power, their successful seizure of power. All the moves against the Provisional government were made in the name of "All power to the Soviets," in the name of "Immediate peace" in the name of transferring power to the Constituent Assembly. When they came to power they got widespread support precisely because the masses were concerned that there would be another counter revolutionary attempt. There had been one attempt in August — the abortive Kornilov coup — they were afraid of another and they looked at the Bolsheviks not as "All power to the Bolsheviks" — that was never said — but "All power to the Soviets," multi-party Soviets. What enabled the Bolsheviks to take power by themselves was that the Mensheviks and the SRS and the Menshevik Internationalists all walked out of the second Congress of Soviets that proclaimed the new government. The Left SR’s refused to get into the government with the Bolsheviks and so the Bolsheviks were able to form a government of their own. More and more historians are looking at the revolution — and I got there very early in my work — as a process starting with the February revolution and ending with the Civil War. On the declaration of NEP [New Economic Policy] as one process with the February revolution being a stage of, the July uprising quite likely a stage, with the October Revolution another stage, with the end of the Constituent Assembly another stage et cetera et cetera. And the civil war is part of it. Lenin’s seizure power was predicated, as you know well Alex, on the assumption that the revolution in Russia would help trigger worldwide socialist revolution starting in Germany. That didn't occur. One of the things I'm finding — I haven't finished my work — you're right that I have focused very narrowly on a couple of years in my work — but I'm finishing up the third, really a fourth volume on Petrograd during the Civil War and the Bolshevik survival in the Civil War. And more and more looking at it from that perspective it looks like one major process which takes that long to sort of complete itself. When Lenin saw that his hopes for early socialist revolutions abroad were not happening he declared NEP, the New Economic Policy, which was sort of a partial reversion on an economic plane to sort of state capitalism. "Socialism in one country" is not Lenin as you know Alex. That was Stalin.

"Socialism in one country" was never dreamed of by any Marxist prior to Stalin. It was kind of this thing where certain measures that were adopted as a result of necessity were turned into a kind of virtue once we get to the Stalin period.

I happen to be firmly on the side of the Bukharin camp led by Steven Cohen, who you may know and who is a New York historian and who is Bukharin’s biographer. He had a much less drastic, slower plan for development which, in my view, would have avoided the great tragedy of the Stalin era.

Well we can certainly debate all those issues but there's no question that external circumstances forced the Bolsheviks to adopt measures that they originally had no intention of adopting.

And I can personally document that for the period October 1917 to 1921. And I do it step by step in the same way that I tried to document what happened in 1917 and 1918. The significant difference is that now I'm able to work in Russian archives. I work in Russian archives two months every year. I live in St. Petersburg and work in the archives. On this next volume — maybe the last volume, I'm not getting any younger — but I'm able to document processes and developments at a lower level that I never could do without access to archives. And one of the things I found is that in every archive file there is a register of who has used those files going back to when the files were first opened, some of them going back to the 1950s or before, and what I find is that most of them haven't been used or a very high percentage of them haven't been looked at and so what that leads me to believe is we have an awful, awful lot more to learn about the Russian Revolution that we still don't know.

Let me just get back to a couple of other myths, for instance the myth that the Bolsheviks spoke in one voice and that basically that was the voice of Lenin. I think your books pretty much destroyed that conception — I mean you're not the only one who's destroyed it — but I think coming from someone of your background with all the scholarship you have available it's very impressive.

Well I thank you. Actually, I came to both conclusions initially in the 1960s when both in the West and in the Soviet Union the Communist Party was looked at as a monolith.

That myth is a myth that's common to both right-wing opponents of the Russian Revolution and Stalinist apologetics for the regime that came later in the 1930s.

Right, and the only point I'm trying to make is that I think I made it fairly early when those things were alive everywhere. And then it was clear just by looking at the April conference. The April conference, Bolshevik conference, was the first conference after the revolution of the party and Lenin was able to participate. It was sharply divided into a Leninist, a center group and moderate Bolsheviks, right wing Bolsheviks — people like Kamenev and Zinoviev. They fought it out and while Lenin sort of won the main fight regarding the direction of the revolution and the continuation of the revolution and transfer of power to the Soviets, the voice of the moderates was very strong and almost half of the Central Committee were made up of moderates. And when some people on the Left said "Well wait a minute we don't want all those moderates," Lenin said, "No we need them. They have ties to the masses and Kamenev’s voice is important." You'll find that in the April conference protocols. So that Lenin tolerated that lively debate and that lively debate was essential in September when Lenin called for the immediate seizure of power in mid-September. It was way too early — it's clear to all historians now that would have been too early — and a majority of the Central Committee and there was a National Conference in Petrograd at the time — a majority of it voted to ignore Lenin's directives and that was to the good of the party. After the Revolution Lenin more or less conceded it. And Stalin conceded that Trotsky had been the main leader to voice the tactics that grew out of the situation on the ground.

Why do you think that after your definitive historical account and others this myth of the Bolshevik seizure of power by a fanatical sect and the authoritarian nature of the Bolsheviks and their “inflexibility”, why do these myths still persist?

They persist for different reasons in different places. In the West they persist partly — say in the United States — because of hostility to Russia that’s still a product of the Cold War and it's now complicated by these charges of Russian intervention in our electoral system and sort of a gut anti-communism, so that several years ago I remember people like Leo Haimson saying that this was a thing of the past, that mythology. But I always didn't feel that way and it's come back stronger than ever as was reflected in all of the New York Times' pieces on the revolution in their series and most recently in the Wall Street Journal. In Russia it's somewhat different. I've been in Moscow and Petersburg several times in the last few months at "1917" conferences, three in Moscow and two in Petersburg and it’s quite clear that at the professional level, among professional historians, serious work is going on and no serious historian is a prisoner of that mythology. But the government, the Putin government, is motivated by a desire for stability and they use nationalism and religious orthodoxy etc., traditional Russian values, implicitly and explicitly, trying to — as we see today — ignore the Revolution and the revolutionary date. They don't want a revolution, understandably — they are another authoritarian regime — and they, that's not in Putin's interest, and so they're helping — sort of encourage — new mythologies. But I want to emphasize that I'm struck by the way a very politicized topic for the whole hundred years since the revolution among serious Russian historians now has become de-politicized and seriously studied.

I note that the Putin regime not only ignored the anniversary of the revolution but they tried to replace it by something called "National Unity Day," which is, I believe, some invention of the Czarist regime that celebrates some uprising against the Poles in the 17th century.

Yes, in any case it's not the same day but what you say is true. The Communist Party has tried to organize a few things the last few days but it's very feeble or everything you say is true.

To end off, could you say a few words about why it's important for us today to remember the Russian Revolution and are there any lessons for us today about what happened in 1917?

Well different people a look at the lessons of 1917 differently. To many Marxists the 1917 revolution, which was the most important event of the 20th century, in the largest country in the world, is an important case study for understanding revolution and making revolution. I just came from a large conference in Brussels day before yesterday. I was there for four days in a workers’ hall in which Lenin spoke in 1914, which was largely populated by devoted communists. and remained communists. And they listen to me very carefully and I know what was in their minds. You know, what can we learn that might be helpful for me. It's very different for me. The Russian Revolution is a terribly important example of why it's important to solve political social and economic problem before they reached a point where a significant percent of the population sees revolution as the only solution to their problems. But then also, I should add, one needs to have an accurate, sensible view of the revolution. If you look at it as a coup the lesson is very different than if it's a major revolution. The two points of view that I described relate to people who see it as a revolution, one side positively the other negatively.

Well I guess on that last question we have to differ a bit because in my view revolutions are unavoidable. But that's a conversation for another time.

But let me just hasten to add that I respect that. My job is to present the most accurate picture I can. I think I have support on the left and in the middle precisely because I am NOT ideological and I don't have a cause except one cause, and that's to try to come as close as I can to delivering a sense of what happened and leave it to people like you and friends of mine who are moderates to decide how best to confront it and deal with it.

I appreciate that and I respect your views. Thank you, Dr. Rabinowitz.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]