Five Book Plan: History of US Political Organizing

For May Day, we present our latest Five Book Plan: L.A. Kauffman, author of Direct Action, selects five essential histories of political organizing in the United States.

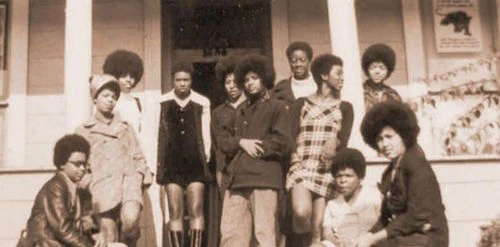

Black Panther women, West Oakland, 1970.

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (ed. David J. Garrow), The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (University of Texas Press, 1987)

Many people know that Rosa Parks was a trained and seasoned political activist before the famous day when she decided to stay in her bus seat. But few are aware of the large, well-organized network of black women in Montgomery that transformed her arrest into a historic campaign of mass noncompliance. This engaging memoir by Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, a key initiator of the Montgomery bus boycott, reveals the behind-the-scenes work of local organizers who had long been waiting and planning for the right opportunity to challenge racial segregation in their city when Parks was arrested. In an era when movements rely heavily on the internet to mobilize participation, there's much to learn from the extraordinary tale of how black women in Montgomery sprang into action the moment Parks was arrested, secretly distributing more than 50,000 leaflets throughout their community in fewer than 24 hours, and thus launching the boycott without tipping off the city's white leadership.

Donna Jean Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (UNC Press, 2010)

Donna Jean Murch's meticulously researched history of the Oakland chapter of the Black Panther Party is really two books in one. She begins with a close study of the postwar mass migration of African Americans from the South to the East Bay, examining the social and cultural underpinnings for the rise of Black Power. But for activist readers, the heart of this book is its second half, where Murch provides a nuanced account of the Panthers' organizing work in Oakland. Most compelling are the sections where she traces how women reshaped the Party's work once many Panther men were jailed or exiled, emphasizing community-based forms of direct action like the famous breakfast program. Through these efforts, which they defined as “survival pending revolution,” Panther women created potent and lasting organizing models that fused service, empowerment, and education.

Francesca Polletta, Freedom Is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements (University of Chicago Press, 2004)

This intriguing work by sociologist Francesca Polletta takes a close look at the evolving ways that American social movements have defined leadership and chosen to structure their organizations and their decision-making processes. Though many grassroots movements of recent decades have embraced radically democratic forms of internal decision-making, there have been striking and important exceptions, as when black organizers within the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee came to view loose and decentralized structures as disempowering and culturally white. Polletta's work carefully tracks debates about internal democracy across decades of movement organizing, considering examples that range from the civil rights and women's liberation movements to the turn-of-the-millennium direct-action-based global justice movement. The sprawling resistance to America's current president can't properly be understood without an appreciation for its distinctive structures and internal practices, giving Polletta's scholarship here great contemporary resonance.

Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (UNC Press, 2003)

This biography of the strategist and organizer Ella Baker remains essential reading 15 years after its publication. Historian Barbara Ransby provides a nuanced account of the life and activism of one of the great political visionaries of the 20th century, whose organizing work and teaching were crucial in nurturing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the black civil rights movement more generally. Baker's powerful, low-key approach emphasized grassroots initiative, collective empowerment, and organic leadership. Like many of the women whose work has profoundly shaped movement history, Baker was neither an orator nor a writer of manifestos. Her influence was at once quieter and deeper than that of the men who formed the movement's visible leadership, and it lives on in the Movement for Black Lives and numerous other organizing contexts today.

Deborah B. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP's Fight Against AIDS (University of Chicago Press, 2009)

No single American grassroots group of the last 40 years has accomplished more than ACT UP, which can take credit for saving millions of lives through its fierce campaigns of direct action and advocacy. Sociologist Deborah B. Gould's compelling 2009 study of ACT UP is well worth revisiting, providing an excellent account of the range of players within the movement and the internal dynamics that helped give rise to their uniquely effective approach. In the grim years before the advent of life-saving HIV medications, death was a constant presence in the AIDS activist world. Organizers within ACT UP famously channeled their grief and fear into anger and action, but often at great personal cost. Gould's perceptive account uses emotion as the lens for viewing and understanding the group's persistence and resilience, as well as the intense debates that divided ACT UP chapters in the group's most difficult years.