Clinton’s Historical Tragedy and the International Women’s Strike: In Support of a Feminism for the 99%

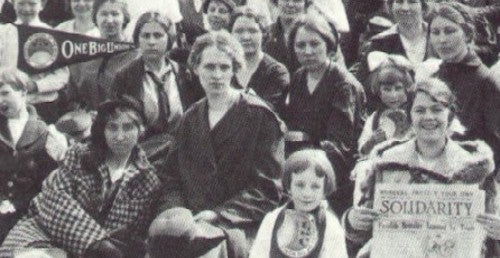

1912 Lawrence Textile Strike

Mired in the recurrent nightmare that is Trump, it is hard to look back and take stock of what happened last week, let alone three months ago. Yet, looking back at Hillary Clinton’s defeat, one may not only see the rising tide of Trump’s hordes, but also the tragic fate of a liberal era. Nowhere is this clearer than in the contradictions embodied by Clinton’s deeply personal but nonetheless strained relation to feminism. Not surprisingly, a broad group of radical and internationalist women are showing the way forward with a call for a feminism of the 99% and coordinating in the U.S. on March 8th with the International Women’s Strike.

Even viewed from a radical perspective, responding on one hand to Clinton’s loss and on the other to Trump’s continuous appalling attacks, we can see Hillary Clinton defeat as having the features of a contemporary tragedy.

The tragedy lies in the precise, if hopelessly ironic, relation of Clinton’s political trajectory, especially her brand of feminism, to the historical path traversed by the society she was trying to lead. Tragically, her candidacy was both conditioned by an obsolete past and out of joint with the current times.

The kind of feminism Clinton took up was intensely individual: one could never stop hearing a silent “it’s my turn” in every public speech. Not only was it individualistic and neoliberal, but it was also hopelessly attached to a political world that recedes ever more into the past: the America of Ronald Reagan and after, of New Democrats and the ascendance of Third Wayism.

All political environments develop and change through time, making positions like corporate feminism entirely capable of mass success at one moment, while deeply alienating at others. Clinton’s third-way, corporate feminism grew out of the Democratic Party’s struggle to reform itself into a winning coalition after the collective disaster of Reagan. But this kind of feminism didn’t so much fail to achieve broad support, as succeed in its designed aim as a rear-guard action at a time when capitalist enterprise was increasing its pull on an already failing Democratic Party. As the feminism of the Democrats became increasingly hollowed by their corporate sponsors, it tended to rely more and more on the faces and language of former struggles, while actually offering far less to both oppressed people of color and the alienated “white working class.”

In short, Clinton was committed to a kind of liberal feminism that could only permit her ascendance when it was already too late. In its tragic lateness, we can now see the limits of a feminism that fully embraced neoliberal common sense and even made it its trademark, nearly corporatizing itself beyond recognition as any kind of feminism.

After Obama and particularly Trump, the transition away from the form of neoliberal politics we have grown accustomed to will be complete. Clinton’s role in it will have been to prove its limits and the necessity of leaving behind a world and a feminism that even at its most progressive and advanced, leaves so many promises unfulfilled. In this sense, Clinton and Trump are not contemporaries.

This is confusing because Clinton and Trump share so much else, especially in class terms, yet Trump recognized the need to offer an alternative. Trump broke with the post-Reagan Republican Party; while Clinton, waiting for her turn, could not mobilize the enthusiasm inherent in promising that a different world is possible. Trump himself was savvy enough to take advantage of the shift that boxed Clinton in: the fundamental misogyny he embodied was emboldened by the increasingly empty or moralistic feminism which insisted on “going high” rather than mounting forceful challenges. Even though Clinton won the popular contest by 2.7 million votes, a different candidate with a more robust strategy would likely have won by a true landside.

No one seriously contends with the fact that if she had been a man, Clinton’s career would have been much different. Perhaps, her candidacy for president would have come much earlier and she would not have had to live in the terrible shadow of Bill Clinton. For this reason, the tragedy is so attached to her person: by all accounts, her campaign ought to have known the strategic risks it was taking. Perhaps it should have known better than to tie Clinton-the-perpetual-candidate to a form of feminism that came out of a very different context, which for all intents and purposes may be called obsolete.

Instead of offering a practical intersection of the issues that democratic politics nominally stands for, Clinton adopted some of the rhetorical strategies of intersectionality while actually adopting a highly constrained version of feminism at odds with it. Socially, the strand of feminism represented by Clinton’s candidacy is characterized by its embrace of neoliberalism, individualism and corporate culture. This feminism may be rightly called “corporate feminism.” There was, however, an alternative feminist banner to take up. In the short term, it could have unified both socialist and left-liberal but militant feminisms insofar as both can view women’s struggle as a path of liberation.

The strand of liberal feminism adopted by Clinton, however, offered a distinctly conservative, corporate mentality made popular by contemporary “lean-in,” you-can-have-it-all, ability-, race-, and class-blind feminism. This approach appealed to the presumed aspirations of middle-class women and the pocket-books of the wealthy, while increasingly alienating the working class. To forestall its downward spiral into double-speak, it had to attempt some semblance of consistency with prior, deeper commitments to women’s liberation.

Within such a framework individual choice become the center of Clinton’s feminism. This was evident in the campaign’s slogan, linking gender with deeply personal avowals of support, rather than with clear commitments on progressive social policy goals. Such a feminism, however, in no way meaningfully addressed the needs of most women today, trans and cis. Even though doing so was politically limiting, this feminism became the centerpiece of Clinton’s campaign. Worse, it took an odd pride in disparaging any concern for the economic and broader social side of things as class reductionism and in its myopia it conjured fanatical Bernie saboteurs around every corner.

What was a side-feature for prior candidates became, for Clinton, a dominant sign that she could not break with the conservative tendencies of the Democratic Party’s rightward turn after Reagan. It thus tied her down when she needed the most flexibility to negotiate rapidly shifting social grounds. Even though it relied on an individualistic conception of choice, it is important to note that Clinton’s public defense of abortion rights, which contrasts to Barack Obama’s timid approach to the subject, was one of the most positive aspects of her campaign.

Yet, when individualism becomes the guiding force for feminism, abstract notions of choice supplant more robust commitments to women’s freedom from social domination. The result is that women wait for their turn, which all too often never comes or, when it does, comes when social conditions make “choice” all but moot. Thus, the tragedy of Clinton’s candidacy: her turn came when it was too late for what she chose to put on stage.

Indeed, the line on which she was standing was closed or, tragically, never really meant to be open in the first place. An individualist perspective on women’s problems will always come too late when it is rooted in a society in which men’s choices dominate. Without confronting the non-egalitarian social structures at its roots, an individualistic, corporate feminism can never transform society. It can only offer a select few the entirely insufficient hope of catching up; of taking their turn; of being represented. The patience of the oppressed is rapidly transformed into a strategy of their oppressor.

It may well have been Clinton’s turn, but the false virtue of patience is rarely justly rewarded, and in the meantime the game was already up. The arrival of Hillary Clinton as a president-in-waiting, who merely had to avoid tarnishing the glory of her inevitable coronation, was only possible once the energies and possibilities of the liberal order, and the liberal feminism it produced, had exhausted their popular appeal. As much was clear to all those millions who even if only in inchoate, quiet, or perverted forms, rejected the liberal order by staying home, voting for Sanders and later Stein, or even, in some instances, supporting Trump as an “outsider”.

There is no possible sympathy with Hillary as a figure, but in the tragedy of her failure we can come to a new knowledge. We can be aware of the historical limits we have reached, as well as the social and theoretical limits of the “feminism” that Clinton embodied and which got us here.

In addition to producing refined self-knowledge, the Clinton tragedy also produced a pathos which should not be underestimated. The senses of loss, devastation, melancholia, and the palpable injustices of the present, in which so much harm is threatened upon so many, must be taken very seriously. The energy produced by the dreaded electoral loss can go into clawing one’s eyes out and refusing to see reality for what it is, as so much of the Democratic Party establishment has been doing since its defeat. Or these energies can be oriented towards an alternative, more radical feminism: one that is congruent with the contemporary conjuncture.

This different path would acknowledge failed strategies and identify with those who have long been searching for alternative feminisms. It is time to rearticulate and fight for a feminism committed to the 99% because only such a feminism can resist without compromise an increasingly chauvinistic social order. In the meantime, more immediate problems impose themselves, literally, through the hand of Donald Trump. How long before an outright attack on women will have to be confronted? Fortunately, every prior attack seems to be energizing more resistance, galvanizing diverse movements and establishing lines of communication and solidarity where there were none before.

On the other side of Clinton’s tragedy, the nature and limits of the constraints imposed by corporate ideology upon feminism are now not only being openly recognized for what they are, but are also being transcended. The upcoming International Women’s Strike, called for by a large contingent of prominent left-wing and black feminists, will be crucial for getting beyond those limits.

We are living an upsurge in women’s activism: events such as the Women’s March in the U.S., and women-lead resistances in South Korea, Italy, Poland, and throughout Latin America are making this clearer every day. Within this renewed movement there is a clear path towards a feminism defined by human liberation, rather than corporate profit. The paths of socialism and feminism are not only converging: it is clearer every day that within both, internal developments lead to the other. Socialism finds itself empty without integrating within it the concerns and problematics of the feminism of the 99%. Feminism, in becoming more and more intersectional, emerges as a strong theoretical and social force against individualism, capitalism, environmental destruction, racism, homophobia, transphobia, and imperialism.

In the end, it will be women themselves who show the world what form their struggle will take, what theories will ground their claims to equality, justice, and emancipation. We can not afford to again ignore the millions of women organizing for such a future.

Francisco Fortuño Bernier, doctoral student in political theory at the Graduate Center, CUNY, and Aaron Jaffe, assistant professor of liberal arts and philosophy at The Juilliard School, are New York based socialists organizing for the March 8th International Women’s Strike.