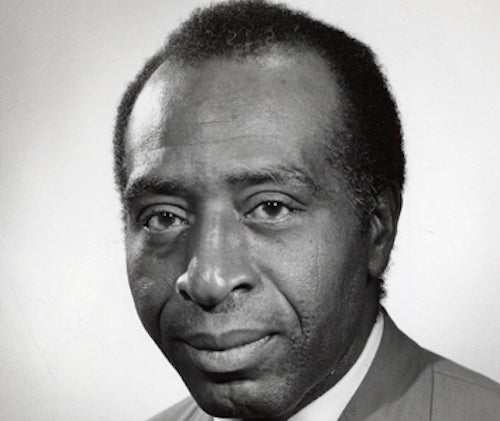

Harold Cruse and the Limits of The Old Left

This post is excerpted from Cedric Johnson's "Between Revolution and the Racial Ghetto: Harold Cruse and Harry Haywood Debate Class Struggle and the 'Negro Question', 1962-8", which will appear in the next issue of Historical Materialism.

The full article examines the series of exchanges between Cruse and Haywood that followed the 1962 appearance of Cruse's "Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American" in Studies on the Left. The first section, reprinted here, offers an intellectual biography of Cruse in the years preceding The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. Johnson goes on to describe Harry Haywood's intellectual formation and his development of the "Black Belt thesis" within the Communist Party before analyzing the debate between the two that commenced with a series of essays Haywood published in Soulbook.

"Revisiting this forgotten exchange between Cruse and Haywood is important on its own terms, for what it says about the character of black political thinking during the sixties," Johnson writes. "Each offered an influential revolutionary-left answer to the problematic of American racial relations, and although much of the vocabulary and conceptual framework they employed — that is, ‘the Negro question’ and the ‘black colony’ — seem antiquated now, their preoccupations and disagreements are relevant to contemporary thinking about black public life, within academe and society more generally."

As direct-action campaigns against Jim Crow grew increasingly frequent and defiant in Wichita, Birmingham, and Greensboro, Harold Cruse enjoyed the cosmopolitan lifestyle of a New York intellectual. By day, he worked at Macy’s department store, and at various odd jobs. And at night, he scribbled and entertained his diverse circle of friends, which included the impressionist painter Norman Lewis and Abram Hill, author of the famed play Striver’s Row. He adored café culture, spending hours conversing, playing chess, and reading in coffee shops like Pandora’s Box, one of his favourite haunts. After the death of the Japanese painter and printmaker Yasuo Kuniyoushi, Cruse inherited his top-floor apartment at 14th Street and Seventh Avenue, making him one of the few blacks living in the Village at that time. At the start of the sixties, Cruse was a man with a growing reputation as an essayist, but the path to his newfound intellectual influence had been a long and twisting one to say the least.

Cruse’s journey into the Communist Party begins before the Second World War. As an adolescent, Cruse was already immersed in the vibrant political culture of Harlem where on most days at the YMCA, he later recalled, “there were Communists debating, black nationalists debating, anti-Communists debating, pro-Communists debating, NAACPers, the whole spectrum of critical opinion was being aired.” A public discussion of Richard Wright’s recently-published Native Son, however, would prove to be a crucial turning point in Cruse’s political and intellectual development. The discussion took place at the Schomburg Collection. Although he later confessed that he “didn’t like the guy much then,” Cruse was curious. The panel discussion featured the leading poet of the Harlem Renaissance Countee Cullen, the famed Jamaican-born writer and Communist partisan Claude McKay, and Christopher Morely, a Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, and author of the 1925 novel Thunder on the Left. The three men set about criticising the book in Wright’s absence. When he finally arrived, Wright made a grand entrance, placed his books and notes on the table and proceeded to silence his critics in a lengthy, skilful rebuttal that astonished the young Cruse. “That night,” Cruse later noted, was “the beginning of my leanings toward the communists . . .” His sympathies were deepening, but it would be his experiences during the Second World War that would propel him into the party’s ranks.

Less than a year after his encounter with Wright, Cruse was drafted into the “citizen’s army,” serving tours in the British Isles, Northern Africa and Italy. He claimed that he “had been indoctrinated in Italy” and was “steadfastly pro-Russian in the war.” Because his regiment was charged with managing supply lines, it was often engaged with the local underground economy. In Italy, however, the situation was volatile as criminal syndicates regularly ambushed US army trucks. In one harrowing episode, Cruse was accosted near the resort town of Terracina. He was held at gunpoint and questioned, but ultimately let go since the truck was not yet loaded with precious cargo. Cruse later confessed that he would not have survived the war had it not been for the Italian communists who provided American troops with information and protection from the local mafia. His time spent among partisans in Italy cemented his commitment to communist politics.

After the war, Cruse settled back into life in Harlem. He joined the Communist Party in 1947 and would remain a member for the next 6 years. During this time, Cruse took a course in Marxist philosophy with Howard Selsam at the George Washington Carver School, an adult-education centre in Harlem that was run by Gwendolyn Bennett, a New Negro poet, and former Howard University art professor. Historian Lawrence P. Jackson writes that “Bennett emitted a personal charm and charisma that had a profound impact in making Communist Party life attractive to Cruse.” Cruse served as librarian for the Daily Worker, often penning theatre and film reviews.

Although he would later claim that repeated visits from the FBI prompted his exit from the party, Cruse’s discontent with the party officialdom, particularly around the matter of black cultural autonomy, had been simmering for some time. He later wrote about the party’s stifling atmosphere, “I could not function in the Left as a creative writer and critic with my own convictions concerning the ‘black experience’.” Inspired by the work of Irish-native and Fabian socialist George Bernard Shaw, the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen and the black vaudeville shows he adored so much as a youth, Cruse wrote four plays during his time in the Communist Party and the years after, but none were ever staged. He also worked on a novel, “The Education of a Rebel," a roman à clef of his party experiences. His breakthrough did not come through fiction, however, but through political essays that conveyed the spirit of the early sixties’ new nationalist militancy, a precursor to black power which drew inspiration from the anti-colonial movements sweeping across the Third World.

The “new nationalism,” or “new Afro-American nationalism” as it was called in some period publications, offered a searing critique of the civil-rights movement. In contrast to the Southern movement with its Christian undertones, and focus on constitutional rights, the new nationalism was defined by its emphasis on economic self-determination, a sharp critique of the civil-rights establishment, and rhetorical posturing toward revolutionary violence. Most black nationalists were sceptical that Southern segregation could be defeated, and the weekly incidences of violence, arrests and sabotage meted out against peaceful demonstrators only steeled their cynicism regarding the prospects of an integrated society. With some exceptions, the new nationalism’s adherents were mostly urban, Northern and west-coast based. Their approach was also anti-colonial in its inspiration and, in many respects, more inter-racialist in practice than black-power militancy later in the decade would become. Cruse describes manifestations of this political and cultural tendency in Harlem in his 1962 New Leader essay, “Negro Nationalism’s New Wave.” “[T]he Afro Americans are here to stay,” Cruse declared, “they will undoubtedly make a lot of noise in militant demonstrations, cultivate beards and sport their Negroid hair in various degrees of la mode au naturel, and tend to be cultish with African- and Arab-style dress. . . . Today it is not uncommon to see Albert Camus’ The Rebel protruding from the hip pocket of a well-worn pair of jeans among the Afro American set.” Cruse captured the sartorial aesthetics of this nascent counterculture that would gain widespread acceptance among African-Americans by the late sixties. In his typical fashion, he distanced himself from this tendency perhaps due to his sense of generational disconnect from the younger radicals he encountered on the streets of Harlem, but Cruse was an active participant in the growing nationalist political tendency. In 1960, Cruse travelled to Cuba with a delegation of black writers organised by Richard Gibson through the Fair Play for Cuba Committee..

Others in the delegation included the Beat poet and playwright LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka); the abstract expressionist painter Ed Clark; historian John Henrik Clarke; the writer Julian Mayfield and his wife Dr. Ana Cordero, a Puerto Rican-born physician; the novelist Sarah Wright and her husband, the radical Jewish composer Joseph Kaye; as well as Robert F. Williams, the famed NAACP leader of Monroe County, North Carolina, who took up arms to defend black lives. Cruse would describe his two weeks in Cuba as “one of the most inspiring experiences I have ever had.” Upon returning to the states, Cruse joined the Organization of Young Men, a small collective of black Manhattan-based artists that included Jones, jazz-saxophonist Archie Shepp, music critic A.B. Spellman, photographer Leroy McLucas, and journalist Calvin Hicks. He also joined the short-lived Freedom Now Party, an all-black organisation, during this period. These experiences, good and bad, would shape his thinking about the limitations of the Old Left and the need for a more assertive black politics, themes that would echo loudly within the emerging nationalist circles and reverberate throughout the decade.

Cruse’s writings during the early sixties constitute a neglected contribution to the development of the New Left. Although Cruse does not identify as part of the New Left, casting himself in a more advisory role at times and openly chastising the “black New Left” at others, his critique of Old Left officialdom, his emphasis on racial-identity politics over notions of class struggle, and his preoccupation with the mass-culture industry and the possibilities of “cultural democracy” all situate him as an important contributor to American New Leftist thinking. Like the left-sociologist C. Wright Mills, Detroit activists Grace Lee Boggs and James Boggs, Frankfurt School political theorist Herbert Marcuse and his other contemporaries, Cruse’s writings represented an attempt to rethink American left-radicalism in light of the taming of mass worker insurgency through bureaucratic trade unionism, McCarthyism, and the consumer society. It is not surprising that his breakout essay would appear in an organ of the emerging New Left. Studies on the Left provided Cruse with a platform to address multiple audiences, the communist partisans he longed to correct, the black radicals whom he hoped to inspire, the slumbering black elite who needed his alarm, as well as those who formed the budding New Left, students, artists and others who might well repeat the mistakes of their predecessors.

Cruse opens the essay “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American” by assailing the failures of “Western Marxists” — his euphemism for the Communist Party leadership — charging that they had not to come to terms with the growing conservatism of white industrial workers, nor did they fully appreciate the implications of the emergence of colonised nations as a revolutionary force. He sees the emergence of the Cuban revolution, and the inability of orthodox Marxists to foresee it, as symptomatic of their intellectual myopia. They expected industrial workers in the advanced capitalist nations to lead the struggle for socialism, but Cruse contends that the colonised world has taken the lead, “The revolutionary initiative has passed to the colonial world,” he argued, “and in the United States is passing to the Negro,” whose relation to the dominant culture is comparable to that of colonial subjects. For Cruse, the Negro is “the American problem of underdevelopment” and the “failure of American Marxists to understand the bond between the Negro and the colonial peoples of the world has led to their failure to develop theories that would be of value to Negroes in the United States.”

Cruse was not alone in his view that “the Negro is the leading revolutionary force, independent and ahead of the Marxists,” as others such as Marcuse and the Trinidadian Pan-Africanist and Trotskyist C.L.R. James asserted the revolutionary potential of the black movement, departing from the orthodox formula of class struggle which viewed the Northern mass worker as central protagonist of socialist revolution. As Cruse more sharply asserted in a subsequent essay, “every social revolution that has taken place since the Russian Revolution has also developed out of industrially backward, agrarian, semi-colonial or colonial conditions while the working classes of the advanced white nations became more and more conservative, pro-capitalist and pro-imperialist [emphasis in original].” Cruse overstates the bankruptcy of organised labour and white workers here and elsewhere in his writings. After all, in the twenty years after 1947, strikes were ten times more prevalent than they would be after 1980. His comments, however exaggerated, point to a set of political problems posed by the institutionalisation of capital-labour conflicts under social democracy. “If the white working class is ever to move in the direction of demanding structural changes in society,” Cruse held, “it will be the Negro who will furnish the initial force.” His articulation of the colonial analogy bore some truth, but the notion coincided with “end of ideology” arguments of the age, most notably authored by Daniel Bell, which viewed the conflict between capital and labour as a settled matter, and working-class, socialist politics as an anachronism.

Cruse saw the potential for solidarity among the colonised around the globe more readily than among those Americans, black and white, who lived and worked side by side to varying degrees from one region of the country to another. The root problem in this all, however, is the extent to which Cruse abandons the critique of political economy and the project of socialist revolution undertaken in places like Cuba, for a form of ethnic-identity politics that was radical in its aspirations, but conservative in practice. In describing the Negro’s colonial status, Cruse minimised the matter of labour exploitation, which along with the extraction of mineral wealth and other natural resources is in fact the driving impetus of most colonial projects. Instead, he emphasised the social effects of proletarianisation, secondary forms of exploitation, and the putative psychological and cultural dimensions of black oppression in the US. “Like the peoples of the underdeveloped countries,” Cruse wrote, “the Negro suffers in varying degrees from hunger, illiteracy, disease, ties to the land, urban and semi-urban slums, cultural starvation, and the psychological reactions to being ruled over by others not of his kind.” Further, he contends that these problems are widely felt among blacks regardless of class: “As a wage labourer or tenant farmer, the Negro is discriminated against and exploited. Those in the educated, professional and intellectual classes suffer a similar fate.” Cruse balks at the possibility of broad-based solidarity among black and white workers. In part, this is understandable given the social and economic conditions of the early sixties. In the South, segregationists were fighting doggedly to keep Jim Crow alive and blacks subservient and disenfranchised. And throughout the rest of the country, even in the most prosperous cities, few blacks enjoyed the full benefits of postwar investment, and most were relegated to inner-city slums and public-housing tower blocks isolated from the middle-class jobs and consumer lifestyles of suburbia. Not all of his contemporaries, however, shared his cynical view of left-politics, and the possibility of working-class solidarity.*Even though he appreciates the notion of working-class interests in a sociological sense, Cruse rejects the viability of a political project built on this basis. In one of his most divisive passages, Cruse boldly asserted that “Negroes have never been equal to whites of any class in economic, social, cultural or political status, and very few whites of any class have ever regarded them as such.” This claim could be easily contested on historical grounds, as it is more of a polemical statement than an empirical one. Here Cruse diminishes the material and ideological differences operating within the black world, in order to raise a call for more effective leadership, a nationalist bourgeoisie along the lines of a colonial territory. The core problem then for Cruse was not primarily one of racial discrimination, but rather “a problem of political-economic, cultural, and administrative underdevelopment.” This brings us to an important contradiction within Cruse’s thinking about black life.

On one hand, he readily acknowledges the class structure of the black population, and notes the different political interests that emerge therein, and yet, on the other hand, he calls for a black-nationalist politics, led by the urban merchant and professional classes, that focuses on economic independence and self-help. Cruse chastises Marxist historians such as Herbert Aptheker for failing to appreciate the class structure of blacks. Although class analysis remains as a vestige, the capitalist political economy is no longer the central object of critical analysis for Cruse, or the target of revolutionary politics. Moreover, while he emphasises the different class interests within the black population, he views black elites as the natural arbiters of the race. The agency and interests of the working classes disappear in his analysis. His thinking onthese matters is in part influenced by E. Franklin Frazier, the Howard University sociologist best known for his 1957 book, The Black Bourgeoisie.† Following Frazier’s analysis, Cruse argues that the black middle class lacks nationalist consciousness and responsibility because of its desire for assimilation. As a result, the black bourgeoisie, unlike that of other ethnic groups we are to assume, has become a “social millstone around the necks of the Negro working class.”Against the paternalism of white absentee landlords, party bosses, and Communist Party officials, Cruse called for a new political focus for black struggles: economic and political control of the racial ghetto. “The Negro nationalist ideology,” Cruse wrote, “regards all the social ills from which the Negroes suffer as being caused by the lack of economic control over the segregated Negro community.” Undoubtedly, Cruse’s ire on these matters of the black elite’s self-interest and their potential connection to blacks overall was sparked by his experiences in the Communist Party ranks where he witnessed other white ethnics who saw no contradiction between their partisan commitments and the maintenance of religious observances, ethnic entrepreneurship, neighbourhood organisations and distinct social life. In fact, he would go on to elaborate on these matters at length in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual.‡

When it came to the matter of territorial sovereignty, however, Cruse’s black-nationalist arguments ran aground, and revealed theoretical limitations that would plague black-power radicals throughout the sixties and seventies. Cruse asked, “Is it not just as valid for Negro nationalists to want to separate from American whites as it is for Cuban nationalists to want to separate economically and politically from the United States?” He asserts that the matter of black national sovereignty should not be viewed in terms of “pragmatic practicalities,” but rather as a political question that “involves the inherent right accruing to individuals, groups, nations and national minorities, i.e., the right of political separation from another political entity when joint existence is incompatible, coercive, unequal, or otherwise injurious to the rights of one or both.” Despite his allusions to political secession, he ultimately demurs, concluding the article by arguing in favour of economic control in more modest terms. This practice of gesturing towards classical national sovereignty, and then settling on a more conservative notion of self-determination — economic and political control of the racial ghetto within the parameters of Cold War America — would become a defining aspect of black-power politics. In 1968, the Republic of New Africa, an organisation formed by two Detroit-born brothers, Richard and Milton Henry, called for the formation of a black nation-state through the combination of five Southern states. And the most iconic black-power organisation, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, demanded as part of their 10-point platform a United Nations-supervised plebiscite for the “Black colony in which only black colonial subjects will be allowed to participate for the purpose of determining the will of the black people as to their national destiny.” Like Cruse, these pronouncements were symbolic, a way for adherents to express their lack of faith in the ability of American liberal democracy to resolve the plight of blacks, and strategic, inasmuch as they shifted public debate away from assimilationist aims towards questions of power and economic development, particularly within inner-city ghettos where investment, jobs and infrastructure were declining.

In the decade after his 1962 essay was published, Cruse’s ideas regarding the purpose and means of black political life would attain widespread acceptance among black radicals who aligned themselves with Third World national-liberation struggles, and eventually, among those blacks who sought out opportunities created by civil-rights reforms, governmental anti-poverty initiatives, and cultural change in corporate America. The essay found devotees among the new nationalist crowd. It was widely read and debatedamong members of the Afro-American Association, a San Francisco Bay area study-group led by Donald Warden whose membership at one time or another embraced a host of influential black-power activists and intellectuals, including Ernest Allen, Leslie and Jim Lacy, Richard Thorne, Cedric Robinson, Ron Everett (later Maulana Karenga, creator of Kwanzaa), and the founders of the Black Panther Party, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) founder Max Stanford claimed the text as a significant influence on his thinking. By the early seventies, the colonial analogy formed the central line of radical black political thinking, and made an impact on Chicano intellectuals such as Rudolfo Acuña and Tomas Almaguer, and academic social scientists like Robert Blauner, William Tabb and Ira Katznelson as well.

In many ways, Cruse’s 1962 essay is descended from the “oppressed nationality” position of the interwar Communist Party. Because of their shared appreciation of Garveyism and its renunciation of “Negro bourgeois reformism,” Cruse speaks highly of Harry Haywood, viewing him in a more favourable light than James E. Jackson whom Cruse dismissed as “the Marxist-Negro Integrationist par excellence.” Still, Cruse offered some sharp criticisms of the “self-determination for the black belt” thesis that Haywood helped to develop as the party’s official line at the Sixth Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1928. The Communists wanted “a national question without nationalism” according to Cruse, and they posed the question too “mechanically because they did not really understand it.” He criticised the policy’s focus on self-determination for the South’s black belt, that region stretching from the alluvial soils of the Mississippi Delta eastward through the cotton-rich counties of Alabama towards the Carolinas, all densely populated by the black peasantry. This regional focus was misguided, according to Cruse, because it neglected the national scope of the Garveyite movement that was largely urban-centred. The “Negro question” was not merely a Southern problem; rather Cruse argued that “the national character of the Negro has little to do with what part of the country he lives in . . . His national boundaries are the color of his skin, his racial characteristics, and the social conditions within his subcultural world.” Haywood had been the sole black advocate ofthe black-belt line at the Sixth Comintern, and for years he had dedicated most of his energies to implementing the policy. It is no wonder that Haywood felt the need to set the younger Cruse straight.

Notes:

* Some like James Boggs offered a nuanced view of the challenges that bureaucratic unionism and automation posed for shop-floor organising. Although Boggs is clear about the racial and ethnic divisions that threaten solidarity, his 1963 book The American Revolution is suffused with a high sense of political optimism. Perhaps the distance between Boggs and Cruse regarding the prospects of interracial working-class solidarity can be explained by their different positions within the left. As an autoworker and union man, Boggs proceeds from the concrete conditions experienced by workers throughout his Chrysler plant and others in the Detroit area. His was a leftist politics that begins with the task of organising workers. Cruse’s leftist politics, however, developed within the world of the New York Communist Party elites, an endeavour that begins with abstract commitment to socialism and moves towards the task of building support for a Communist Party programme. He and Boggs viewed the class war from very different vantage points, as distinct as the general’s command post from the barbed-wired trenches of the battlefront. Cruse’s frustrations with party officialdom no-doubt led away from any faith that working-class solidarity could be anything other than an abstraction, even though there was evidence to the contrary all around him. "Except for a very small percentage of the Negro intelligentsia," Cruse concluded, "the Negro functions in a subcultural world made up, usual of necessity, of his own race only."

† Cruse writes approvingly: "Frazier shows that the failure of the Negro to establish an economic base in American society served to sever the Negro bourgeoisie, in its 'slow and difficult occupational differentiation' from economic, and therefore cultural and organizational ties with the Negro working class. Since the Negro bourgeoisie does not, in the main, control the Negro 'market' in the United States economy, and since it derives its income from whatever 'integrated' occupational advantages it has achieved, it has neither developed a sense of association of its status with that of the Negro working class, nor a 'community' of economic, political, or cultural interests conducive to cultivating “nationalistic sentiments."

‡ Two chapters from Cruse’s most well-known work stand out on this matter of competing ethnic allegiances and class solidarity, "1920’s–1930’s – West Indian Influence" and "Jews and Negroes in the Communist Party." Aside from his attacks on artists like playwright Lorraine Hansberry, these are the most detested and controversial chapters in the book. So much so that lengthy rebuttals have been penned decades after the book’s publication by those who contest the accuracy of his historical analysis and who view Cruse’s arguments as ethnocentric and unfair to particular groups.

Read more in Historical Materialism.