Haymarket and Its Context (Part 2)

Read Part 1 of this May Day excerpt from Philip S. Foner and David R. Roediger's Our Own Time: A History of American Labor and the Working Day here.

Set in this context of continuing struggle over the working day, the FOTLU’s decision to press on with its bold 1884 plan to enforce the eight-hour system with a mass strike on May 1, 1886, was not extravagant. The demand was well timed — raised during a depression which made unemployment an issue and maturing during a recovery which made workers readier to strike without fear for their jobs. Of the seventy-eight FOTLU unions polled in 1885, sixty-nine supported the May 1 plan. Working-class militancy meanwhile grew in early 1886 as the Knights of Labor led the Southwest strike against Jay Gould’s railroad empire and attracted hundreds of thousands of new members.

The FOTLU, realizing that cooperation by the larger Knights of Labor would go far toward building the mass strike, bid again for Powderly’s support. Gabriel Edmonston, FOTLU secretary, wrote the Knights during the summer of 1885 to ask their aid, but received no reply. At the September 1885 Knights convention, an FOTLU request was read, but, after Powderly denounced the date of the action as “not…suitable” and the use of a strike as “not…proper” the delegates passed a vague resolution in favor of the eight-hour system. Still, the press frequently linked the Knights to the May 1 movement and, to Powderly’s consternation, Knights’ organizers used eight-hour promises to enroll members, who passed local resolutions in support of the mass strike. On March 13, 1886 Powderly promulgated a “secret circular” which rebuked organizers for invoking the Knights’ support for the May 1 strike and insisted that the time was ripe for education and not action. The lack of official Knights’ support seriously hurt the movement, both by lessening its numbers and by sowing confusion, but in many locales, Knights of Labor did participate in the eight-hour strikes.

If the FOTLU’s plan got mixed support from the Knights, it eventually received enthusiastic backing from the trade union wing of the anarchist movement. Within the International Working People’s Association (IWPA), an anarchist body of several thousand, two tendencies coexisted. The first, led by the German expatriate Johann Most and based around the Freiheit newspaper in New York City, advocated “propaganda by the deed” and saw individual terror as leading to a society without authority. The second wing, propounding the “Chicago Idea” of anarchism, was more an anarcho-syndicalist movement. Developing mainly in Midwestern cities with a rich heritage of police and Pinkerton violence against the labor movement, the syndicalist wing drew many radicalized immigrant and American-born trade unionists in the IWPA. At the 1883 Pittsburgh IWPA convention, the two leading syndicalists, Albert Parsons and August Spies, joined Most on the platform committee and secured his acquiescence to a platform accepting trade union work as an arena for anarchist agitation. The “Pittsburgh Manifesto” also outlined the anarchist society of the future and promised “that nobody need work more than a few hours a day.”

The syndicalist wing of the anarchist movement produced only a loose body of theory. Its syndicalism, its belief in a future society organized around working-class organizations, was not fully developed. Leaders could, for example, enthuse about a utopia vaguely based on consent and freedom, or could pinpoint “the Granges, trade unions [and] Knights of Labor assemblies” as the “embryonic groups of the ideal anarchist society.” Similar imprecision marked the group’s ideas of force. At various times the “Chicago Idea” appeared to mean advocacy of individual terror, of mass insurrection, and of working-class self-defense. Most commonly, the last mentioned function of violence was stressed, although leaders engaged in a good deal of loose “bomb-talking,” as the socialist writer Floyd Dell termed it. Such countenancing of violence gave the press the chance to attack the eight-hour movement through its most radical IWPA wing, but the positive aspects of syndicalist participation outweighed such bad publicity.

The syndicalists brought a class analysis, energy, and an appeal to the unskilled and immigrant worker to the eight-hour campaign. A persistent myth regarding the syndicalists is that they entered the eight-hour movement late and as opportunists. Such a charge, raised by the prosecution during the trial, and by historians, is an oversimplification. Albert Parsons, for example, had acted as the chief English-language spokesperson in Chicago for the Workingmen’s party when the group demanded an eight-hour day during the 1877 railroad strike. He led in the building of the July 4 eight-hour demonstrations of 1878 and 1879 — demonstrations that brought Ira Steward and George McNeill to Chicago — and held office in the Eight-Hour League. During 1879 he publicly differed with his Socialist Labor party comrades, Thomas Morgan and George Schilling. Parsons argued that eight hours was a revolutionary demand. In 1880 he joined four other labor leaders as a member of the eight-hour lobby in Washington, D.C. That same year he withdrew from active electoral activity in part because of his conviction “that the number of hours per day that wage-workers are compelled to work…amounted to their practical disenfranchisement.” Throughout the early 1880s, Parsons attempted to build revolutionary unionism by consistent activity in favor of basic class demands — including shorter hours — both as a member of the International Typographical Union and as a founding leader of the Central Labor Union. Others of the Haymarket martyrs similarly noted that the length of the working day abetted their radicalization and pointed with pride to their record as activists in the shorter-hours and trade union movements.

The confusion that provided slim justification for the view that the IWPA syndicalists had no sincere concern for the eight-hour day stemmed primarily from two articles that appeared in the English-language anarchist newspaper Alarm in 1885. The first article, an August reply to a FOTLU circular asking cooperation in the May 1 campaign, branded the FOTLU plan a “waste of precious time and effort.” A month later the Alarm pledged not to “antagonize the eight-hour movement” but argued that eight hours meant nothing if capital still ruled. This posturing, which termed the eight-hour day, “more than a compromise…a virtual concession that the wage system is right,” came in part from a desire to placate the Most faction of the IWPA which barely countenanced revolutionary unionism and regarded all reform as anathema. It also gained credence because IWPA organizers, influenced by a literal application of Marx’s ideas on surplus value, had generally ceased to preach eight hours but had instead argued that justice would be served if the capitalist received just the two, three, or four hours of work that it took for labor to produce the value of its wages. But the anti-May 1 position, arrived at with Parsons traveling away from Chicago, was speedily overturned. The syndicalists came to endorse the struggle as “a class movement” from which they did not want “to stand aloof,” and from January until May of 1886, threw their energies into the May 1 campaign.

The syndicalists provided skilled organizers and added a sense of the dramatic to the movement. Particularly in Chicago, IWPA women such as Lucy Parsons, Lizzie Swank-Holmes, and Sarah E. Ames did vital organization in the needle trades while Albert Parsons, Samuel Felden, Michael Schwab, and Oscar Neebe enrolled cloakmakers, packinghouse workers, clerks, and painters into the eight-hour effort. The Chicago IWPA members had familiarity with a flair for the theatrical. In the 1879 eight-hour parade Albert Parsons’ union local sent a float bearing a working press churning out shorter-hours materials, and in 1885 the IWPA captured huge publicity by protesting the opening of the Chicago Board of Trade with leaflets headed “Workmen, Bow to Your Gods!” As May 1 approached, the IWPA publicity machine again cranked up when the Central Labor Union sponsored a festival April 25 rally on the Chicago lakefront.

The IWPA also made a contribution by organizing armed workers’ militias ostensibly capable of defending strikes. Since the 1877 railroad strike, various socialist rifle clubs had sprung up as a response to police violence. The growth of these “Study and Defense Clubs” in Detroit, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Saint Louis, and Chicago during the 1884 and 1885 derived mainly from IWPA influence. From October 1885 until the strike, the syndicalists emphasized that strikers would have to defend themselves. While these calls to arms must be described as shows of bravado by a still-tiny group, they represented an attempt to show how a mass strike might be defended. Moreover, they were the lone attempts by a labor organization to speak to what was a prime concern of prospective strikers — the possibility of attacks by private and public police.

Finally, the IWPA broached what was the main issue of the strike for the unskilled workers. At the time the FOTLU did not state that no wage cut should accompany the transition to the eight-hour system. Publications of the craft unionist Trades and Labor Assembly of Chicago openly offered to take wage cuts to win less hours, but the IWPA raised banners reading “Eight Hours Work for Ten Hours Pay.” The formulation was crucial in enlisting the support of the lowly paid unskilled laborers who could not afford to lose wages.

As May 1 drew near, it became clear that the FOTLU did not have sufficient forces to coordinate a national campaign. Instead of a centralized effort of craft unions, strike propaganda went out under the auspices of various local coalitions. In New York City the craft unions did most of the work. In Chicago Knights of Labor leader George Schilling, a socialist, joined the IWPA at the head of organizing efforts. Knights and the craft-oriented Trades and Labor Assembly predominated in Cincinnati, while an Eight-Hour League unified the forces of the Knights and others in Milwaukee.

But localism did not mean weakness. By March the campaign forced city councils in Chicago and Milwaukee to grant the eight-hour day to municipal laborers. The cigarworkers successfully demanded a nine-hour shift in January as preparation for later events. By mid-April John Swinton’s Paper, a labor weekly, reported “eight-hour agitation everywhere.” The Wisconsin commissioner of labor and industrial statistics later wrote that hours “was the topic of conversation in the shop, on the street, at the family table, at the bar, in the counting room, and the subject of numerous able sermons from the pulpit.” Newspapers speculated on the size of the coming strike and bewailed the influence of “Communism, lurid and rampant” in the eight-hour ranks.

Meanwhile, workers smoked “Eight-Hour Tobacco” and wore “Eight-hour Shoes” — products already produced in shops working the shorter day — and sang hymns of the movement including:

We want to feel the sunshine;

we want to smell the flowers;

We’re sure that God has willed it.

And we mean to have eight hours.

We’re summoning our forces from

shipyard, shop and mill;

Eight hours for work, eight hours

for rest, eight hours for what we will.

In the warm weather of late April many workers must have followed the logic of the young immigrant Cincinnati furniture worker Oscar Ameringer and, with “buds and blue hills” beckoning, resolved to fight for more leisure. Thousands jumped the gun by striking before May 1.

When May 1 arrived, a massive strike wave accompanied it. Its exact proportions remain unclear, but the number of strikers certainly far exceed the 100,000 which some observers had predicted in April, although it fell short of the million participants predicted by Albert Parsons. The traditional estimates made by the Commons group put the number of workers involved at 340,000. Of these, 190,000 are said to have struck and 150,000 to have demonstrated or won a voluntary reduction in hours: 45,000 in New York, 32,000 in Cincinnati, 4,700 in Boston, 4,250 in Pittsburgh, 3,000 in Detroit, 2,000 in Saint Louis, 1,500 in Washington, and 13,000 in other cities. These guesses err on the low side. For example, a thorough study of Milwaukee suggests between 14,000 and 20,000 strikers, and federal statistics indicate that in the strike center of Minneapolis-Saint Paul about 2,500 walked out. Government data on Saint Louis, which fail to mention several of the local strikes, nonetheless number over 4,5000 participants in hours strikes in late April and May. For the District of Columbia the figures should be corrected to upwards of 2,200. Probably 400,000 and perhaps half a million workers joined in the agitation. They did so not only in urban centers, but in smaller cities and rural towns — in Montclair, New York; Duluth, Minnesota; Argentine, Kansas; South Gardiner, Maine; Mobile, Alabama; Lynchburg, Virginia; Galveston, Texas; Cedarburg, Wisconsin; and a score of other localities.

With perhaps 90,000 demonstrators on the streets, with 30,000 to 40,000 on strike, with 45,000 having already benefited from decreases in hours, with “every railroad in the city…crippled [and] most of the industries…paralyzed,” Chicago had the most eventful May 1. In New York City Samuel Gompers addressed a crowd of 10,000 in Union Square after a torchlight parade. Ameringer, carrying a piece of wood shaped into a dagger, found the May 1 demonstration in Cincinnati to be a fitting beginning to a “jolly strike” and note the presence of “a workers battalion of four hundred Springfield rifles.” In Milwaukee, where 7,000 struck on May 1, there were picnics and parades the following day. Eleven thousand Detroiters marched and 5,000 struck in Troy, New York, where Italian railroad laborers improvised red flags by tying their handkerchiefs to pickaxes.

The May 1 strike featured processions of roving pickets who spread the strike. This meant that the already large number of strikers would swell further as the strike went on. In Milwaukee, for example, the second two days of the strike yielded at least 7,000 more participants. A like pattern developed in Chicago, Saint Louis, and Cincinnati. Two events, both involving police action, intervened to stem the strike’s momentum. The celebrated events at Haymarket occurred three days after the strike’s start, while the equally blood Milwaukee tragedy followed one day later.

The prelude to Haymarket was a chance May 3 confrontation at the McCormick Harvester plant. Labor relations at the reaper plant had long been grim. After armed Pinkertons attacked strikers there in April 1885, the Metal Workers’ Federation Union at the factory organized an armed section. Trouble flared again the following February when the company violated an agreement not to discipline union activists and locked out workers for protesting. The lockout generated a bitter strike which continued in May. The strike did not concern hours, but the factory was located near the Black Road site at which the Lumber Shovers’ Union, 10,000 of whose largely immigrant members had struck for eight hours, held a rally.

Six thousand lumber workers turned out for the afternoon rally at which IWPA member August Spies was scheduled to speak. As Spies’s brief, tepid address neared its end, the McCormick factory bell sounded day’s end for the strikebreakers manning the plant. Members of the crowd left the rally to taunt those leaving work. When the stick-and-stone-throwing protesters caused the strikebreakers to retreat toward the factory and Harvester’s windows were menaced, police fired into the crowd. One demonstrator died immediately from wounds, and probably three more died later.

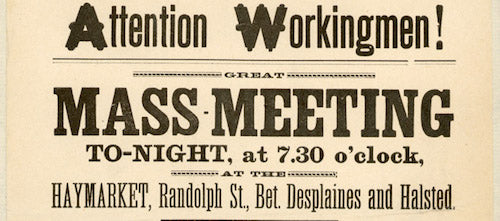

Spies, who saw the massacre, dashed off a circular at the office of Arbeiter-Zeitung, the paper he edited. Printed in English and German, the circular called on workers to “rise…and destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you,” in the former language and advised “avenge this horrible murder” in the latter. Spies later testified that the heading “Revenge! Workingmen! To Arms!” was added without his knowledge and that he insisted on the excision “Arm yourselves and appear in full force” from a circular issued the following day. Nonetheless, the protest meeting set for 7:30 on May 4 promised to be tense because of the circulars, the inflammatory accounts in the newspapers, and the saber-rattling of police captain John Bonfield.

Throughout the day of May 4 strikers and police clashed, but the night’s meeting proved surprisingly small. With a spring storm looming and other protest meetings slated in the neighborhoods, the demonstration did not draw more than 3,000. The crowd filled only one end of the huge Haymarket area and left ample room for police informants and Mayor Carter Harrison to observe. Spies led off with a short address directed against the press. Parsons, who had just returned from Cincinnati and knew little of the Chicago events, followed with an impressive oration that argued for socialism and urged workers to arm themselves, but cautioned against individual terror. A thunderstorm interrupted Samuel Felden’s speech, the last of the evening, and sent home two-thirds of the listeners, including Harrison. Felden was about to finish when the police issued an order to disperse. As he protested that the meeting was peaceful, 180 police waded into the crowd on Bonfield’s order. Seconds later a sputtering, flickering bomb flew through the air and exploded in front of the police, killing one and wounding fifty. The police then fired at the protesters and inflicted perhaps seventy wounds, at least one of them fatal. Seven police died later, mostly from wounds received in the gunfire. “NOW,” headlined the Chicago Inter-Ocean, “IT IS BLOOD.”

The wheels of injustice turned swiftly. Massive police dragnets began immediately after the bombing. Police arrested hundreds and searched scores of homes and labor organizations, usually without warrants. Arrests of IWPA members, at first with no charge and then on the charge of conspiracy, mounted. In all, thirty-one indictments came down in connection with the murder but, when informers and the wildly improbable were weeded out, eight were selected for trial. Captain Michael Schaack supervised the dragnet with, as Henry David observes, “an immoderate appetite for fame.” Schaack produced a steady stream of uncovered “plots” complete with planted bombs. The press raged against anarchist “vipers” and “serpents.” The New York Tribune and the Chicago Inter-Ocean editorially convicted IWPA leaders of murder on May 5; the New York Times waited until May 6; Harper’s Weekly delayed conviction until May 8.”

Police raids and journalistic vituperation hurt more than the IWPA. The hysteria spilled over to brand socialists, eight-hour advocates, and immigrants as threats to order. No fine distinctions applied. The Chicago Furniture Manufacturers’ Association listed society’s enemies as “any communist, anarchist, nihilist, or socialist or any other person denying the right of private property.” In Chicago, center of the May 1 movement, labor was put on the defensive. Elsewhere, outlandish rumors enjoyed credence and the “anarchist threat” legitimized repressions. In Cincinnati, Ameringer recalled, the strikers heard newsboys shout “Anarchist bomb-throwers kill one hundred policemen…in Chicago” — news which descended “like a very cold blanket.” On the day the news came, the city’s mayor deputized 1,000 special police. Two days later he called out the state militia.

Reaction to Haymarket in Milwaukee followed a bloodier scenario than in Cincinnati. A large contingent of Polish strikers, mostly unskilled workers, led strike processions which emanated each morning from Saint Stanislaus Church. The processions succeeding in closing a large brewery, the West Milwaukee railroad shop, a stove works employing 2,500, and Reliance Works of Allis farm machine company. On May 4 three companies of militia prevented the closing of the North Chicago Rolling Mill in Bay View without violence. The next day, after Haymarket, the mayor banned “crowds upon the streets or other public places.” Wisconsin’s governor called in additional troops.

Still the marchers went forth, but assured Milwaukee Journal reporters that they “had no intention of making an attack on the militia or company property, and simply wished to show that they had not been intimidated.” As they neared the North Chicago Rolling Mill, the militia’s commander issued a single and, according to the Journal, inaudible, order to stop. Then, apparently acting on orders from the governor, the troops fired directly into the crowd. Nine men, eight Poles and a German, died from their wounds. In the post-Haymarket atmosphere a coroner’s jury praised the militia for “ordering the firing to cease” and returned no murder indictments. Meanwhile, nearly fifty workers were indicted, and some served six-to-nine month terms for “riot and conspiracy.” The local press reported, “From all parts of the state messages have come commending Governor Rusk for the promptitude with which he acted.” There were only mild objections when the employers made cash gifts to the militia companies involved.

Such an atmosphere devastated the eight-hour movement, and by mid-May the campaign lost its impetus. Still, it was far from a total failure. In Cincinnati strikers continued to argue that the law, a recent eight-hour statue, was on their side. According to a recent study, over 70 percent won some positive settlement of hours and/or wages, and nearly an eighth secured hours reductions with no pay cuts. Nationally, nearly 200,000 workers shortened their days, some by as many as five hours. As many as 87,000 may have one the eight- or nine-hour day in New York City alone, and some trades, such as the fur workers and cigarmakers, enjoyed success in many cities. Gompers later estimated that the net effect of the 1886 action cut the working day by an hour. Federal statistics show the average working week of all those who struck over time in 1886 as going down from just less than sixty-two to less than fifty-nine hours per week.

The most direct effect of the Haymarket bombing was to decimate the leadership of anarcho-syndicalist movement in the United States. That movement, personified by the Haymarket defendants, received a speedy trial and death sentence in Chicago. The trial, which began on June 21, was openly an inquisition against the IWPA rather than a murder investigation. Its judge, Joseph E. Gary, cooperated with the prosecutors to assure that the defense would have to use its preemptory challenges in jury selection against candidates whose state biases, and even relationship to the victims, merited disqualification for cause. The result was a twelve-man jury which included no industrial workers, but was composed of managers, salesmen, contractors, and businessmen.

The prosecution, led by State’s Attorney Julius S. Grinnell, made some attempt to marshal evidence that the defendants had met in a “Monday night conspiracy” to plan the bombing as part of a general insurrection, but it could place only two of those on trial at the alleged planning session — an open public meeting. On the opening day of the trail, Grinnell found a more promising line of argument to which he would return throughout the proceedings. Defending “our institutions” from “Anarchy,” Grinnell argued that “these defendants hourly and daily for years, have been sapping [those] institutions, and that where they have cried murder, bloodshed, Anarchy and dynamite they have meant what they said.” The words of the syndicalists, wrenched from context or reported by a hostile press, would convict them when evidence of their actions could not. Seven years later, in discussing the case, Gary commented that the identity of the bomb-thrower was “not an important question.”

Albert Parsons grasped a serious problem of the defense when he wrote in his notebook during the trial, “It can and must be shown that all this arming was for resistance and not for attack.” But because of Gary’s rulings, and because of past “bomb-talking” in the IWPA, such a point could not be made. On August 20 the jury recommended death for all those charged save Neebe, whose sentence was set at fifteen years. The Chicago Tribune suggested raising a fund to reward the jurors. Headlines read, “Chicago, the Nation and the Civilized World Rejoice.”

Not all rejoiced. As the executions approached, a strong, international defense movement developed. After the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the verdict while acknowledging faults in the trail and after the U.S. Supreme Court denied appeals, the unions entered the defense effort in force. The newly organized American Federation of Labor, heir to the FOTLU, pled for clemency and both the United Trades of New York and the Central Labor Union of New York City called for protest meetings. Gompers and McGuire spoke and wrote on the behalf of the condemned men. Despite Powderly’s continued refusal to defend the anarchists, to whom he said the labor movement owed nothing but a “debt of hatred,” local assemblies of the Knights acted. The Chicago Knights of Labor, after following Powderly for a time, switched to a position of support for the accused. In England the many protest meetings featured speeches by George Bernard Shaw, William Morris, and Eleanor Marx-Aveling, and in France members of the Chamber of Deputies petitioned against the executions. Distinguished Americans, including Congressmen Robert Ingersoll, Governor Benjamin Butler, Senator Lyman Trumball, entrepreneur George Francis Train, future Socialist Labor party leader Daniel DeLeon, writers William Dean Howells, John Swinton, and Henry Demarest Lloyd, and former abolitionists Moncure D. Conway and John Brown Jr., all participated.

The most outstanding figures of the defense campaign were the defendants themselves. Spies, who spoke first to the court, addressed the judge: “Now these are my ideas. They constitute a part of myself. I cannot divest myself of them, nor would I, if I could. And if you think you can crush them out…by sending us to the gallows…I will proudly and defiantly pay the costly price. Call your hangman.” Neebe asked to be killed with his comrades and Parsons refused to plead for a pardon. Even on the gallows where Parsons, Engel, Spies, and Fischer died on November 11, 1887, the condemned men remained unawed. Parsons demanded, “Let the voice of the people be heard!” as his own voice was stilled. Spies’s last words were simply, “There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!”

The long term effects of the Haymarket affair unfolded slowly. Certainly the labor and eight-hour movements suffered, both from repression and from the rapid decline of the Knights of Labor, a decline related to that organization’s division over whether or not to back the Haymarket defendants. When the leadership of the Knights ordered Chicago packinghouse workers, on strike in October 1886 in defense of the eight-hour day they had gained in May, to return to work, the prestige of the order further plummeted. On the other hand the AFL grew steadily throughout the post-Haymarket years, and the United Labor Party (ULD), an independent political group calling for the eight-hour day among other demands, grew spectacularly in 1886. The ULP took nearly a third of the votes in the New York City mayoral election, where its candidate was Henry George, the celebrated land reformer who also had a record of shorter-house advocacy. And the ULP took more than a quarter of the votes in embattled Chicago.

That the anarchists should have stimulated a brief renaissance of political action by labor is not merely supreme irony. In the wake of Haymarket, the mass strike to secure the shorter day had suffered the same fate as had the efforts at legislative reform of the late 1860s. It had been tried and found no panacea. In the space of two decades had come graphic illustrations that the state could neither be relied upon to grant eight hours, nor ignored in mounting an eight-hour struggle against employers.