Toni Negri was a reader and continuer of Karl Marx, in an astonishing combination of literality and freedom

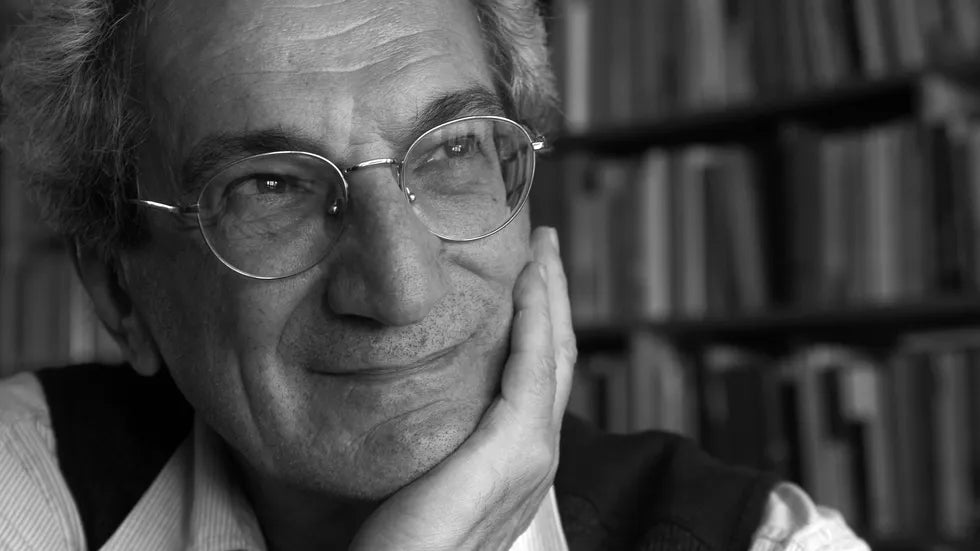

Étienne Balibar praises the work of his friend the Italian thinker Antonio Negri, who died on 16 December. Negri theorised creative resistance and new forms of revolt in the face of globalised capitalism.

This obituary was originally published by Le Monde on December 2023.

The first thing that struck one about him, in addition to his incredibly youthful figure at any age, was his unique smile – sometimes carnivorous, sometimes ironic or full of affection. It grabbed me the first time we met, outside a seminar at the Collège International de Philosophie. He had escaped from Italy thanks to an election that temporarily released him from prison. We were devastated by the rise of Reaganism and Thatcherism, which shattered the illusions born of the Socialist victory of 1981. What could we do in this debacle? ‘But revolution!’ explained Toni, beaming with optimism. It was advancing through countless social movements, each more inventive than the last. I wasn’t sure that I really believed him, but I came away freed from my dark mood and won over by him for good.

I hadn’t taken Negri’s famous seminar on Karl Marx’s Grundrisse, organised in 1978 at the École Normale Supérieure by Yann Moulier-Boutang, which I was told was both fascinating and esoteric. And I was almost completely unaware of the operaismo of which he was among the leading spirits.

For me, Negri was the theorist and practitioner of ‘workers’ autonomy’, whom the Italian state, gangrened by the collusion between its army and the American secret services, had tried to make the mastermind of far-left terrorism; an accusation that collapsed like a house of cards, but which sent him behind bars for years. Before and after his imprisonment, surrounded by comrades whose lives had quietened down yet whose passions remained intact, he was the pillar of this French Italy, the mirror image of the Italian France we had dreamed of establishing before 1968. Taken together, around a few journals and seminars, they were to launch a new philosophical and political season. Through his provocations and his studies, Negri would be its inspiration.

[book-strip index="1"]

Freedom and the emancipation of labour

I will just give a few elliptical reference points, chosen according to my own affinities. Spinoza, of course. After the thunderclap of The Savage Anomaly in 1982 came yet more essays, inspired by the words ‘the rest is missing’, written by the publisher on the blank page of Spinoza’s Political Treatise, which had been interrupted by the death of the Hague recluse in 1677.

Unlike many others, Negri did not seek to reconstitute this missing ‘rest’, but to invent it, following the thread of a theory of the power of the multitude, which combines the metaphysics of desire and democratic politics against any transcendental conception of power resulting from the collusion between law and the state. Spinoza, the anti-Hobbes, the anti-Rousseau, the anti-Hegel. The brother of the Neapolitan insurgents whose figure he had once borrowed. Discussion for and against this ‘subversive Spinoza’ has been constant, and marked the great ‘Spinoza renaissance’ of our time.

We can move on to the problem of freedom and the emancipation of labour, which starts with Spinoza and converges with Foucault, but also with Deleuze, because of the profound vitalism at work in the opposition between the ‘biopolitics’ of individuals and the ‘biopower’ of institutions. It reinstates within the very idea of power the opposition formerly established between power and might, and allows us to take up, as the very essence of the revolutionary process, the old Leninist theme of ‘dual power’, but shifting it from an opposition between state and party to an opposition between state and movement.

The foundations for this are already to be found in Negri’s 1992 book Insurgencies. For me, this is one of the great essays in political philosophy of the last half-century, in dialogue with Schmitt, Arendt and the republican jurists, on the basis of a genealogy that goes back to Machiavelli and Harrington. All ‘constituted power’ stems from an insurrection that it seeks to bring to an end in order to tame the multitude, and correlatively finds itself up against the excess of constituting power over the very revolutionary forms of organisation that it gives itself.

A communism of love

Let us return to Marx to conclude. From beginning to end, Negri was his reader and his continuer, in an astonishing combination of literality and freedom. Marx Beyond Marx (1979) meant taking Marx beyond himself, not ‘refuting’ him. This was already the sense of his analyses of the ‘state-form’ in the days of militant operaismo. It is the meaning of his ingenious extrapolation of the Grundrisse’s analyses of industrial machinism (the ‘general intellect’), which take on their full significance in the age of the computer revolution and ‘cognitive capitalism’, whose ambivalence they allow us to grasp from the point of view of the mutations of social labour. An endless combat between ‘dead labour’ and ‘living labour’.

[book-strip index="2"]

And this, of course, is the meaning of the great trilogy co-written with Michael Hardt: Empire (2000), Multitude (2004), and Commonwealth (2012), later followed by Assembly (2017), in which, against the tradition of ‘scientific’ socialism and its problematic of transition, he develops the thesis of a communism of love, with Franciscan and Lucretian accents. This is already here, not in the ‘pores’ of capitalist society, as Marx wrote and Althusser took up, but in the creative resistance to exclusive ownership and the generalised state of war in globalised capitalism. It is embodied in revolts and experiments that are constantly reborn, with the new ‘commons’ that they bring into existence.

So, there is always this famous optimism of intelligence, which we now understand has nothing to do with the illusion of a guaranteed sense of history, but conditions the productive articulation between knowledge and imagination, the ‘two sources’ of politics. Toni Negri leaves us today with the strength of his desire and his concepts.

Translated by David Fernbach