The Nightmare and Dream of Autonomous Policing

Despite a wave of criticism, both the NYPD and LAPD have moved forward with plans to implement Quadruped Unmanned Ground Vehicles – more commonly referred to as "Robot Police Dogs" – into their departments' fleets. In this excerpt from After Black Lives Matter, Cedric G. Johnson breaks down the implications of such a move.

Sgt. Henry Lawson is a twenty-three-year veteran of the Wardenville Police Department. He keeps his tie loosened. Drinks coffee continuously. Still takes a smoke whenever he can, and curses e-cigarettes as the devil’s making. He’s chief detective on staff, it is a little after 5 a.m. and he’s just begun a homicide investigation. A shot locator picked up the sound of a single discharge around 4:45 a.m., and a responding officer discovered the deceased after talking to neighbors.

Lawson pulls onto the curb. Not much to see at the crime scene. A single gunshot wound to the chest, likely a small caliber handgun. No signs of struggle. The victim is seated in a peeling vinyl Barcalounger. His television and gaming system are still paused. Half a pepperoni pizza, a translucent green ganja pipe and spent cans of cheap beer sit on the coffee table. The victim is a twenty-three-year-old white male, Chris Lincoln, known to his friends as “Chopper.” He split his time between working the afternoon shift at a local Tim Horton’s, selling prescription meds and occasionally uploading unboxing videos of collectible action figures.

From his car, Detective Lawson uses software that aggregates data from numerous social media sites, records of restricted drug purchases from pharmacies throughout the state, missing persons and open search warrants, the census and other databases. Within a few minutes, he is able to map a network of Lincoln’s friends, illustrated in a web of encircled photos with colored border-shading ranging from green to yellow to red to reflect the intensity of interactions and plausibility of suspects. Lawson also integrates this emerging social map with metropolitan and regional gang databases, as well as arrest and conviction records from the local police department and state and federal agencies. What emerges is not only a visual display of Lincoln’s social world, spanning nearly a thousand or so social contacts, but how and through whom that world is connected to the region’s narcotics economy. His aunt Viola Lincoln shows up as an intense connection, but she has no prior convictions, only unpaid tickets. Lawson momentarily opens a web search of her name, finding mostly articles in the local weekly about Viola’s volunteer work, a Pinterest trove of mid-century modern furniture and décor ideas, and her stray online photos. Some of Lincoln’s more intense social connections are less savory. Lawson focuses on the prime suspects generated by the software’s algorithm—individuals with close ties, prior offenses, especially for violent crimes, and geographic proximity. Three high matches emerge, their photos encircled almost completely in red—Raymont Sandifer, Julia West and Antonio Mathias. Sandifer is immediately ruled out. He has been in the county jail for the last week waiting to post bail. West and Mathias were in town based on voluntary social media location info. West is brought in for questioning and released, but Mathias can’t be located.

Lawson requests a networked surveillance camera search for Mathias’s late model Ford Mustang, pearl white with a black fender panel waiting to be painted. Within minutes Lawson is able to pull up the route of Mathias’s movements over the last twenty-four hours, using public and private surveillance as well as traffic cameras. Two pertinent details emerge. His car was near Chris Lincoln’s house the night of the murder, and its most recent location is 1372 West Lowell Street. Lawson searches the location and the previous suspect mapping—the house is the residence of Mathias’s girlfriend Tangela Neil, though legally belonging to her father according to public records. Mathias’s fingerprints also match those found on beer cans at Lincoln’s place. Lawson contacts the department’s Autonomous Tactical Unit (ATU) specialist, and they consult with the department chief. The three decide to proceed with an arrest at midnight based on the determinations of the prime suspect software, the print matches and the location of Mathias’s car the night of the murder. Closed-circuit security video also recorded Mathias and Lincoln entering a nearby convenience store around 6 p.m. the night before. A warrant is issued before Lawson refills his coffee and fishes out his next cigarette.

The ATU specialist, Crystal Kinsey, is a recent university graduate who is interned with a nationally recognized robotics company. Technically, she’s still subcontracted through that company, lending her expertise in drones and industrial robotics to the local police department. Kinsey and Lawson park their tactical van at the end of the 1300 block of West Lowell Street. Kinsey releases two small aerial drones that circle the perimeter of Tangela Neil’s property. Hypersensitive audio recording equipment as well as thermal cameras detect at least three persons inside the house, one apparently a young child. Lawson gives the ok signal for the arrest process to begin. Three robotic dogs fitted with body armor and non-lethal weapons are dispatched. All three are equipped with multi-directional cameras. Two proceed to the rear of the house, where the residents are located, and one bot approaches the front door. Their movements are smooth and virtually silent against the whir of nearby highway traffic and the occasional burst of laughter and muffled music flowing from the wood-frame houses lining the block. The dogs give an audible warning of the arrest and simultaneously force open the front and back doors—each dog’s “head and neck” is actually a reticulated claw. They release non-toxic smoke grenades into the house to disorient the occupants and reduce visibility. The lead bot locates the child, presents her with a stuffed animal and plays the theme music from the highest-rated children’s show in that market. Softly grasping her hand, the police dog leads her through the haze and out the front entrance. Kinsey wraps her in a Mylar blanket and takes her to the rear of the police van, out of sight. Neil is caught first in the living room. Disoriented, she submits, is cuffed and led outside. Mathias barricades the bedroom door in the chaos and escapes through a window. He sprints towards a nearby patch of pinewoods, but the third bot fires a bolo-like device that wraps his lower legs, causing him to crash shoulder first into a firewood rack in the neighbor’s backyard. Lawson secures his hands with flexible cuffs.

Kinsey and Lawson load the suspects into the van, reading them their Miranda rights. Inside the van’s detention compartment, mounted retinal scans of Mathias and Neil record the arrest and upload the time, address and other pertinent information to the state’s criminal offense cloud archive. A relative of Neil, who lives two blocks over, is already on hand to take the daughter for the night. Lawson savors some menthol while Kinsey inspects the drones and dogs as she stores them for recharging and records any damage.

An arrest that may have taken days if not weeks of legwork, interviews and interrogation, and required a small phalanx of SWAT officers, was executed in less than twenty-four hours, before the coroner could deliver a full autopsy report on Lincoln’s body, and with few warm-blooded workers involved. Wardenville’s police department had shrunk from nearly ninety beat cops and office staff down to forty in less than a decade. After years of budget shortfalls and population loss, city officials had to find other ways to maintain public safety in this rusting midwestern city of 35,000.

Of course, Wardenville is fictional, but all the technology brought to bear here already exists and could easily be implemented to meet the needs of cash-strapped jurisdictions, depopulated regions and cities where police brutality and the public relations and legal morass such incidents created have prompted reductions in waged employees. Scientists, military and law enforcement personnel have debated the ethics of using robotics and artificial intelligence in the field for some time now, but except for fleeting protests over the use of weaponized drones, much of the US public still sees unmanned weaponry as the realm of science fiction. Given the many existing uses of big-data policing, the ongoing legislation to weaponize drones in select states, and the incredibly agile and dexterous robotic police dogs developed and piloted by Boston Dynamics, the world of autonomous policing sketched here is already at hand.

These tools do not stand outside the nexus of capitalist class relations, institutional power and bourgeois ideology; rather, such technologies emerge from that cradle, bearing the interests of their creators. Against hegemonic notions of impartial scientific truth, Andrew Feenberg reminds us that technological development is socially constituted and deeply ideological.1 In every technology—that is, in every solution to a problem, whether a toaster, automated car wash or dating app—we find the condensation of those historically discrete interests, social values and biases that precipitated and shaped their invention.

Technology-intensive policing is not merely a matter of using smarter tools, as politicians, police superintendents and engineering wunderkinds might have us believe, no more than the adoption of robotic spot welders on automotive assembly lines or shipping containers in industrial ports were simply a matter of efficiency. The latter technologies were born in response to barriers to capital accumulation, namely the organized power of autoworkers and longshoremen, respectively. New technology-intensive forms of policing have been precipitated by different historical forces, including the pressures of various publics, victims’ families, civil libertarians, prisoners’ rights advocates and, more recently, Black Lives Matter demonstrations, who have demanded peace, safety, more racial justice and greater transparency from police departments. Intelligence-led policing and automated technologies provide a means of circumventing the kind of genuine reforms demanded by antipolicing forces, reforms that would require social redistribution and substantial changes to the current order. The use of drones either with remote operation, artificial intelligence or some combination of these, replaces human judgment and responsibility with algorithmic decision-making and bureaucratic detachment, potentially evading the legal morass that might stem from shootings committed by flesh-and-blood officers. Such technologies are born out of established modes of policing, inheriting their biases and values, without altering the broader class relations policing exists to manage, and yet producing new problems. Protests that focus on the extremes of police violence without fully contesting the social hegemony of policing, how and why policing retains the consent of vast portions of the public, will only further the adoption of these technologies, especially when robotics engineers and other scientists have also gained the trust of publics and popularized the efficacy and humanity of their design solutions.

The robotic police dogs described in the Wardenville hypothetical are inspired by the actual designs of Boston Dynamics, a firm that has captivated public imagination over the past two decades with viral videos depicting highly mobile, nimble, humorous and multifunctional robots. The rise of Boston Dynamics also reveals the ideological and technical linkages between the American military and domestic policing. With an infusion of DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) funding, the company was called upon to develop a pack robot, the Big Dog, capable of carrying heavy equipment alongside troops into the battlefield. The software and engineering developed in that original Big Dog design have since spawned a few generations of quadruped and biped robots, with numerous potential military and industrial applications. Each generation of Boston Dynamics robots has developed greater traction, improved capacity to navigate uneven terrain, and greater speed and functionality. The Cheetah, for instance, set the land speed record for a quadruped robot, clocking a higher peak speed than 100 meter world-record holder Usain Bolt.

The introduction of the Spot robot and other similar technologies will likely be seen as a boon to law enforcement. The Spot requires routine maintenance but not a living wage, medical leave or recreation time. Like all consumer goods, the Spot will have a lifespan, either because of attrition or planned obsolescence, but it will not require a retirement banquet, commemorative plaque or set of golf clubs, nor, to the delight of fiscal conservatives, will it need a pension. While the videos of the Spot are charming, once such technology is integrated into the entrenched modes of policing it will become no different from a taser, Monadnock PR-24, Dodge Enforcer, Glock 9mm, body camera, Mossberg riot shotgun or any other technology used by police to enforce state power.

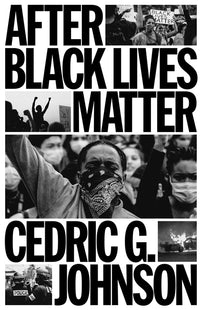

The above is a slightly edited excerpt from After Black Lives Matter by Cedric G. Johnson.