Tariq Ali on the pattern of Anglo-American attacks on Iraq

"The lesson is not that aggressive territorial expansion is a crime that cannot be allowed to pay. It is that to carry it off a state must act in the interests of the West as well: then it can be astonishingly successful."

Originally published in the New Left Review, in 2000.

On May 23rd of this year the British Defence Minister Geoff Hoon was questioned in the House of Commons about the pattern of Anglo-American attacks on Iraq. He replied:

Between 1 August 1992 and 16 December 1998, UK aircraft released 2.5 tons of ordnance over the southern no-fly zone at an average of 0.025 tons per month. We do not have sufficiently detailed records of coalition activity in this period to estimate what percentage of the coalition total this represents. Between 20 December 1998 and 17 May 2000, UK aircraft released 78 tons of ordnance over the southern no-fly zone, at an average of 5 tons per month. This figure represents approximately 20 per cent of the coalition total for this period.

In other words, over the past eighteen months the United States and United Kingdom have rained down some 400 tons of bombs and missiles on Iraq. Blair has been dropping deadly explosives on the country at a rate twenty times greater than Major. What explains this escalation? Its immediate origins are no mystery. On 16 December 1998 Clinton, on the eve of a vote indicting him for perjury and obstruction of justice in the House of Representatives, unleashed a round-the-clock aerial assault on Iraq, ostensibly to punish the regime in Baghdad for failure to cooperate with UN inspections, in fact to help deflect impeachment. Operation Desert Fox, fittingly named after a Nazi general, ran for seventy hours, blasting a hundred targets.

The fire-storm continued through the following year, unhindered by NATO’s Balkan War. In August 1999 the New York Times reported:

American warplanes have methodically and with virtually no public discussion been attacking Iraq. In the last eight months, American and British pilots have fired more than 1,100 missiles against 359 targets in Iraq. This is triple the number of targets attacked in four furious days of strikes in December … By another measure, pilots have flown about two-thirds as many missions as NATO pilots flew over Yugoslavia in seventy-eight days of around-the-clock war there.

In October American officials were telling the Wall Street Journal they would soon be running out of targets—‘We’re down to the last outhouse’. By the end of the year, the Anglo-American airforces had flown more than 6,000 sorties, and dropped over 1,000 bombs on Iraq. By early 2001, the bombardment of Iraq will have lasted longer than the US invasion of Vietnam.

Yet a decade of assault from the air has been the lesser part of the rack on which Iraq has been put. Blockade by land and sea have inflicted still greater suffering. Economic sanctions have driven a population, whose levels of nutrition, schooling and public services were once well above regional standards, into fathomless misery. Before 1990 the country had a per capita GNP of over $3,000. Today it is under $500, making Iraq one of the poorest societies on earth. A land that once had high levels of literacy and an advanced system of healthcare has been devastated by the West. Its social structure is in ruins, its people are denied the basic necessities of existence, its soil is polluted by uranium-tipped warheads. According to UN figures of last year, some 60 per cent of the population have no regular access to clean water, and over 80 per cent of schools need substantial repairs. In 1997 the FAO reckoned that 27 per cent of Iraqis were suffering from chronic malnutrition. UNICEF reports that in the southern and central regions which contain 85 per cent of the country’s population, infant mortality is twice that of the pre-Gulf War period.

The death toll caused by deliberate strangulation of economic life cannot yet be estimated with full accuracy—that will be a task for historians. According to the most careful authority, Richard Garfield, ‘a conservative estimate of “excess deaths” among under five-year-olds since 1991 would be 300,000’, while UNICEF reporting in 1997 that ‘4,500 children under the age of five are dying each month from hunger and disease’—reckons the number of small children killed by the blockade at 500,000. Other deaths are more difficult to quantify but, as Garfield points out, ‘UNICEF’s mortality rates represent only the tip of the iceberg as to the enormous damage done to the four out of five Iraqis who do survive beyond their fifth birthday’. In late 1998, the UN humanitarian coordinator for Iraq, former assistant secretary-general Denis Halliday, an Irishman, resigned from his post in protest against the blockade, declaring that the total deaths it had caused could be upwards of a million. When his successor Hans von Sponeck had the temerity to include civilian casualties from Anglo-American bombing raids in his brief, the Clinton and Blair regimes demanded his dismissal. In late 1999, he too resigned, explaining that his duty had been to the people of Iraq, and that ‘every month Iraq’s social fabric shows bigger holes’. The so-called Oil-For-Food sanctions, in place since 1996, allow Iraq only $4 billion of petroleum exports a year, when a minimum of $7 billion is needed even for greatly reduced national provision. In a decade, the US and UK have achieved a result without parallel in modern history. Iraq is now, Garfield reports, the only instance in the last two hundred years of a sustained, large-scale increase in mortality in a country with a stable population of over two million.

What justification is offered for exacting this murderous revenge on a whole people? Three arguments recur in the official apologetics, and are relayed through the domesticated media. Firstly, Saddam Hussein is an insatiable aggressor, whose seizure of Kuwait not only violated international law, but threatened the stability of the entire region; no neighbour will be safe till he is overthrown. Secondly, his regime was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction, and was about to acquire a nuclear arsenal, posing an unheard-of danger to the international community. Thirdly, Saddam’s dictatorship at home is of a malignant ferocity beyond compare, an embodiment of political evil whose continued existence no decent government can countenance. For all these reasons, the civilized world can never rest until Saddam is eliminated. Bombardment and blockade are the only means of doing so, without improper risk to the citizens of the West.

Each of these arguments is utterly hollow. The Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, a territory often administered from Basra or Baghdad in pre- colonial times, was no exceptional outrage in either the region or the world at large. The Indonesian seizure of East Timor had been accepted with equanimity by the West for the better part of two decades when the ruling family fled Kuwait. Still more pointedly, in the Middle East itself, Israel—a state founded on an original process of ethnic cleansing—had long defied UN resolutions mandating a relatively equal division of Palestine, repeatedly seized large areas of neighbouring territory, and was in occupation not only of the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and the Golan Heights, but a belt of Southern Lebanon at the time. Far from resisting this expansionism, the United States continues to support, equip and fund it, without a murmur from its European allies, least of all Britain. The final outcome of this process is now in sight, as Washington supervises the reduction of the Palestinians to a few shrivelled bantustans at Israeli pleasure. The lesson is not that aggressive territorial expansion is a crime that cannot be allowed to pay. It is that to carry it off a state must act in the interests of the West as well: then it can be astonishingly successful. Iraq’s seizure of Kuwait was not in the West’s interest. It posed the threat that two-fifths of the world’s oil reserves might be controlled by a modernizing Arab state with an independent foreign policy—unlike the West’s feudal dependencies in Kuwait, the Gulf or Saudi Arabia. Hence Desert Storm.

So much for expansionism. As for the deadly threat from Iraqi weapons programmes, there was little out of the way about these either. So long as the regime in Baghdad was regarded as a friend in Washington and London—for some twenty years, as it crushed Communists at home and fought Iranian mullahs abroad—few apprehensions about its armaments drive were expressed: chemical weapons could be used without complaint, export licences were granted, extraordinary shipments winked at. If nuclear capability was another question, it was not from any special fear of Iraq, but because since the sixties the United States has sought, in the interests of big-power monopoly, to prevent their spread to lesser states. Israel, naturally, has been exempted from the requirements of ‘non-proliferation’—not only stockpiling a large arsenal without the slightest remonstration from the West, but enjoying active support in the concealment of its programme. Once the Iraqi regime had turned against Western interests in the Gulf, of course, the possibility of it acquiring nuclear weapons suddenly moved up a routine US agenda to the status of an apocalyptic danger. Today, there is no stitch left on this scarecrow. On the one hand, the nuclear monopoly of the big powers, always a grotesque pretension, has collapsed—as it was bound to do—with the acquisition of weapons by India and Pakistan, with Iran no doubt soon to follow. On the other hand, Iraq’s own nuclear programme has been so thoroughly eradicated that even the super-hawk Scott Ritter—the UNSCOM inspector who boasted of his collaboration with Israeli intelligence, and set up the raids that triggered Desert Fox—now says there is no chance of its reconstitution, and that the blockade should be dropped.

Lastly, there is the claim that the domestic enormities of Saddam’s regime are so extreme that any measure is warranted to get rid of him. Since the Gulf War ended without a march on Baghdad, Washington and London have not been able to proclaim this officially, but they let it be understood with every informal briefing and insider commentary. No theme is more cherished by left-liberal camp-followers of officialdom, eager to explain that Saddam is an Arab Hitler, and since ‘fascism is worse than imperialism’, all people of good sense should unite behind the Strategic Air Command. This line of argument is, in fact, the ultima ratio of the blockade. In Clinton’s words, ‘sanctions will be there until the end of time, or as long as Saddam lasts’. That the Ba’ath regime is a brutal tyranny no one could doubt—however long Western chancelleries overlooked it while Saddam was an ally. But that it is unique in its cruelties is an abject fiction. The lot of the Kurds in Turkey—where their language is not even allowed in schools and the army’s war against the Kurdish population has displaced countless thousands of people from their homelands—has always been worse than in Iraq, where— whatever Saddam’s other crimes—there has never been any attempt at this kind of cultural annihilation. Yet as a valued member of NATO and candidate for the EU, Ankara suffers not the slightest measure against it, indeed can rely on Western help for its repression. The kidnapping of Öcalan supplies a fitting pendant to that of Vanunu, accompanied by soothing reportage in the Anglo-American media on Turkey’s progress towards responsible modernity. Who has ever suggested an Operation Urgent Rescue around Lake Van, or a no-fly zone over Diyarbakir, any more than a pre-emptive strike on Dimona?

*

For all the devastation it has caused, without hope of durable solution, the upshot of intervention in the Balkans pales besides the balance sheet in Iraq. There, the result has been a veritable Massacre of the Innocents. Let us take the vanity of our leaders at its word. Clinton and Blair are personally responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of small children, callously slaughtered to save their joint ‘credibility’. If we take a low-range figure of 300,000 children under five, and enter a provisional estimate of the premature death toll among adults at another 200,000, we arrive at one of the largest mass killings of the past quarter century. Moderate figures like Dennis Halliday put the total much higher, at a million or more. By comparison, the Gulf War itself was a small affair: not more than 50,000 dead. Saddam’s bloodiest crime—the one that enjoyed Western complicity—was his attack on Iran, which cost his people 200,000 casualties, the Iranians even more. The genocide in Rwanda wiped out some 500,000. It is sufficient to say that the number of infants and adults destroyed by the siege of Iraq appears to be in that league. If we want a more exact political accountability, Clinton—in power since 1992—can be apportioned nine-tenths of the dead, Blair—in office since 1997—a third. Since without America and Britain, the blockade would have been lifted long ago, the role of other Western leaders, craven though it is, need not be reckoned.

In 1964, within a few months of the Wilson government coming to power, Ralph Miliband warned the sixties generation, many elated by the end of thirteen years of Conservative rule, and willing to take any signs of reform at home as the tokens of a progressive administration, that it was a fatal mistake to lose sight of Labour’s foreign policy, already quietly docked into Washington. That, he predicted, would be likely to define the whole experience of the regime. Within a year he was proved right. Wilson’s support for the American war in Vietnam, once Johnson had dispatched the US expeditionary force in 1965, exposed to view the full extent of the political rot within Labourism. The miserable end of Old Labour after a decade of barren office was written in advance, in this futile, servile collusion with a vicious imperial war. In the United States, the struggle against the Vietnam War finished off Johnson and in the end, indirectly, Nixon too; in Britain, it ensured Wilson, Callaghan and their colleagues the complete disdain of anyone of spirit under twenty-five, not to speak of disillusioned elders.

The siege of Iraq is not another war in Vietnam. Its scope, means and target are of a lesser scale. But there is another difference too. This time, Britain is not just lending diplomatic and ideological support to American barbarities; it is actively participating in them as a military confederate. The record of Old Labour, shameful as it was, is little beside this odium. What would Miliband be saying of New Labour, as its jets take off for yet another bombing raid on the shattered and famished remnant of a Third World society, whose children are dying like flies at the behest of Blair’s machine? Prevailing political discussions of the government appear never to have heard of them. They revolve tranquilly round such questions as the value of its ‘New Deal’ jobs programme, Working Families Tax Credit or projected health spending, just as in America, talk turns to the effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit, extra cents on the minimum wage, or notional pension schemes. The issues themselves are not unimportant. But as hang-dog pretexts for tolerance of the Clinton or Blair administrations, they are niceties. Too many children have been dispatched by these Herods, safely beyond the ken of Anglo-American ‘gut instincts’, for them to have any weight. These contemptible regimes need to be fought, not wistfully propitiated.

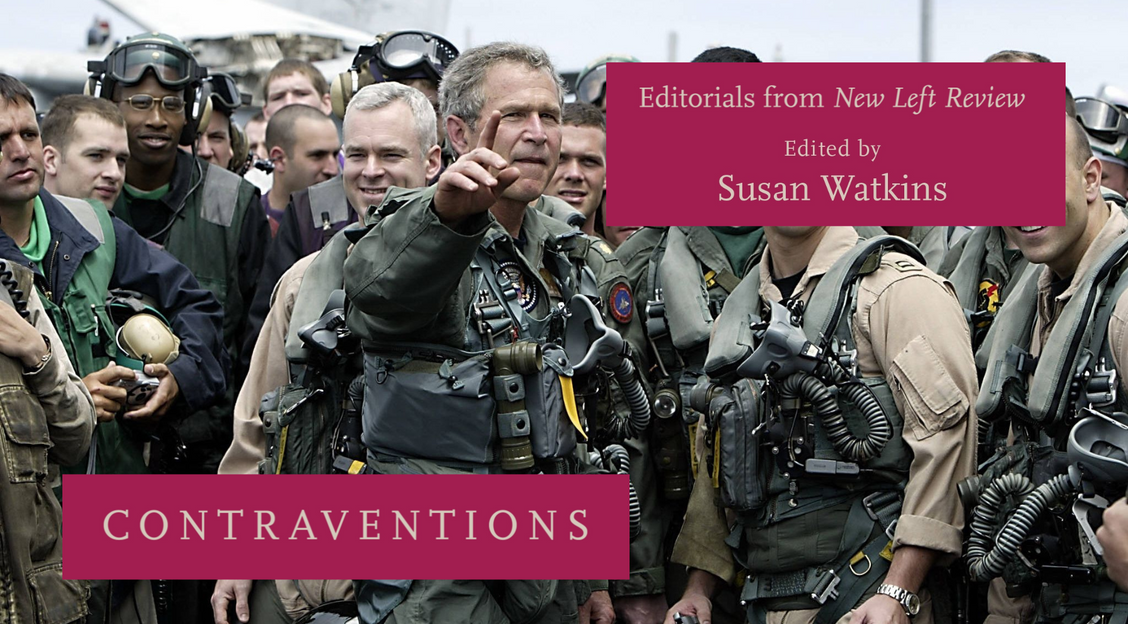

— An adapted excerpt from Contraventions: Editorials from New Left Review, Edited by New Left Review and Susan Watkins.

[book-strip]