Ominous Developments Surround Lumumba | Andrée Blouin

“On the eve of independence, this great country had to undergo such things—to write its history in letters of tears and blood. Poor Congo!”

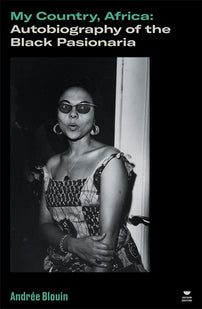

![[Photo: Andrée speaking to the crowds at a rally. Idiofa, Belgian Congo, 1960]](http://www.versobooks.com/cdn/shop/articles/Verso_Southern_Questions_blog_copy.png?v=1736161822&width=1128)

[Photo: Andrée speaking to the crowds at a rally. Idiofa, Belgian Congo, 1960]

The following is an excerpt taken from My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria by Andrée Blouin.

I had met many political personalities since my arrival in the Congo, but never Patrice Lumumba. This revolutionary was already a hero that mad year in the Congo—1959—and his name was written in letters of gold in the Congo skies.

Lumumba had attentively followed Gizenga’s work and supported his platform of Congo unity. During Gizenga’s electoral campaign he had sent Gizenga several telegrams of congratulations. A collaboration between the MNC and the PSA was logical, and the two leaders were working toward this.

One day, Gizenga said to me, “Tonight I’m going to meet Lumumba and I’d like you to be with me. I want your impression of him. You women sometimes have more intuition than we men.”

At that time Lumumba had just returned from the Round Table in Brussels. There he had participated with the Belgians in discussions on independence, his wrists still scarred from the manacles he wore during his three months in prison.

Patrice was his characteristically natural self at our meeting with him. It was he who came to the door of his residence to receive us. Laughing, his white teeth shining, he shook our hands warmly. He wore black trousers and a white shirt. With a feline step he led us into his receiving room. I felt a great deal of joy in his easy manner.

After he had made us welcome, he turned to me. Constantly moving his fine, long, nervous hands, he said, “It’s good of you to come to the Congo and help us, Madame Blouin. We’re sincerely grateful. Until now our country has been a chasse gardée for the Belgians. But soon it will belong to us. We’re willing to fight hard for it. You’ll see.”

He said this firmly, but with a smile. He went on.

“We’re facing serious problems in forming the government. The Belgians are trying to divide us, turn us against one another. They’re putting spies everywhere. On the very eve of our independence, they’re still intent on destroying our unity.”

Smiling, full of good spirits, he continued to talk, his hands moving restlessly as he expounded on the obstacles to be overcome to prepare a viable new system. I listened intently, my admiration for him growing. Before the evening was over, I felt sure I was in the presence of a great man. I said so to Gizenga, later, as we were separating.

“I’m glad I met Lumumba. He’s brave and he’s sincere. Above all, he is committed. That’s the important thing. He is passionately committed.”

Gizenga, silent as usual, was listening. “He will be your friend,” I predicted, happy that I felt this to be true. “One of your best friends, politically. He won’t disappoint Africa,” I added, in words that now seem prophetic.

The next day, the historic agreement uniting the two largest parties, the PSA and the MNC, was signed by Lumumba and Gizenga. This was an important step forward for the nationalists.

But there was much work to be done as the intrigues multiplied around us. Each evening Pierre, Antoine, and I returned to Lumumba’s home, late, when he would not be disturbed, to report on our work of the day and confer with one another. As there was a curfew in Leopoldville, Lumumba arranged a laissez-passer for each of us. He always laughed as if he were neither tired nor worried, although we knew how hard he was working and how many problems he faced as he tried to bring together reliable elements to form a nationalist government.

A constant line of candidates for positions presented themselves at his home. As we discussed the merits of these aspiring officials, our friendship developed. It was the special friendship that is to be found only among those who are working heart and soul for the same cause.

One evening he had something special to show us. He took a dossier out of his briefcase. “Look!” he said, triumphantly. “Here’s a document from the Leo secret police. One of our friends managed to get hold of it for us. Reports on the three of us.” (Pierre was not there that evening.)

The first report concerned Lumumba. It complained at length about how he was no longer as grateful and docile seeming as he had been at the Round Table when he thanked the Belgian authorities for agreeing to hold the Round Table, and to let him take part in it. “He has changed his tune,” the report said. “His work is now damaging the Belgian government program.”

……………

The Congo crisis was upon us. New political groups were being formed every minute on the basis of fresh news about the possibilities of their leaders’ positions. Riots broke out in many places, taking numerous victims. Nerves were stretched to the breaking point. The atmosphere crackled with hostility.

The Belgians were a depressing sight. Pitying themselves, trembling with fear, rage lurking in their eyes, they saw an enemy in every Congolese, who in turn saw them as their declared foe.

It would be unfair to say that all the whites in the Congo were detestable. But the sum of misery inflicted on the blacks by the many far eclipsed the deeds of kindness of a few. Rare and precious indeed was a friendship with a white.

The imperialists, who called themselves “the moderates,” organized one plot after another against the nationalists, who wanted to make a common front with Lumumba. No trick was too petty, no treachery too heartless for the imperialists’ purposes. There was nothing they would not stoop to in order to achieve their purposes. They even resorted to cultivating the tribal chiefs. For years these chiefs had been only figureheads among their people, serving mainly to collect taxes for the Belgians. Now these chiefs were decked out in a pretended new prestige and authority, for one reason only: to open old tribal wounds and set the people against one another.

It was pitiable and disgusting beyond words to see the dreadful farce enacted: the Belgians cozying up to these old chiefs whose significance had been in tatters for so long. These chiefs, displayed as objects of curiosity in a Brussels exhibit of second-rate folklore … these chiefs, so amusing in their exotic ornaments except that their dark skins frightened the blond babies of noble Belgium … these chiefs, charmingly illiterate, whose signature was a thumbprint, that thumbprint agreeably affixed to a document depriving them of the right to manage their own affairs … these chiefs who had been dishonored and discarded and who sometimes did not understand when their race was being insulted … these were the same chiefs, forgotten in the night of time, who now became the new instruments for the Belgians’ intransigence and greed.

And they let it happen, the chiefs. They let themselves be used for the white trusts’ iniquitous purposes. For decades they had worn only the poorest cotton cloths and had known cold in their simple straw huts. Now in the pride of their new pagnes they rose in arms against their racial and ethnic brothers, to tear their land asunder.

On the eve of independence, this great country had to undergo such things—to write its history in letters of tears and blood. Poor Congo!

My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria by Andrée Blouin is out now. It is part of the Verso Southern Questions series: books focusing on decolonisation and its aftermath.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]