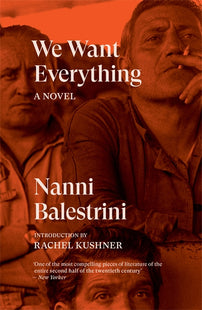

May Day reading: We Want Everything

"It’s not fair, living this shitty life, the workers said in meetings, in groups at the gates. All the stuff, all the wealth that we make is ours. Enough. We can’t stand it any more, we can’t just be stuff too, goods to be sold. Vogliamo tutto — We want everything."

Nanni Balestrini’s classic 1971 novel, We Want Everything, is narrated by a frustrated, aimless, and nameless man. He drifts from southern Italy to the north, in search of work that will allow him to live “the good life.” Instead he arrives at Italy’s largest automobile factory, Fiat’s Mirafiori plant, where he finds the situation similar to everything he’s seen before: hard work, shit pay, and miserable workers. Our narrator doesn’t dwell long in his frustration, as he’s soon swept up in collective struggle, part of the Italy’s Hot Autumn.

As part of our May Day reading we present this excerpt from We Want Everything.

To celebrate May Day, all books are 40% off until May 16, 2022 at 11:59PM EST. See our May Day reading!

I’d had all kinds of work in my life. Construction worker, porter, dishwasher in a restaurant, I’d been a labourer and a student, which is also a job. I’d worked at Alemagna, at Magneti Marelli, at Ideal Standard. And now I’d been at Fiat, at this Fiat that was a myth, because of all the money that they said you made there. And I had really understood something. That with work you could only live, and live poorly, as a worker, as someone who is exploited. The free time in your day is taken away, and all of your energy. You eat poorly. You are forced to get up at an impossible hour, depending on which section you’re in or what work you do. I understood that work is exploitation and nothing more.

Now this myth of Fiat was ending. I’d seen that a job at Fiat was the same as a construction job, the same as washing dishes. And I’d discovered that there was no difference between a construction worker and a metalworker, between a metalworker and a porter, between a porter and a student. The rules the teachers applied in those technical schools and the rules the bosses applied in all the factories where I had been were the same. So this posed a great problem for me. That is, I thought, what do I do now? What do I do, what do I have to do?

I hadn’t stolen yet, I’d never had a gun. I’d never been friendly with the so-called low-life. At least I would have had an outlet, whether for feeling pissed-off, for my dissatisfaction, or for my needs, my material life. I wasn’t a doctor or a lawyer, a professional. So it wasn’t as if I could say, OK, I’ll become a thief or a freelancer. I was really nothing; I couldn’t do a thing.

Yet I had this desire to live, to do something. Because I was young and blood was coursing through my veins. The pressure was pretty high, in other words. I wanted to do something. I was ready for anything. But it was clear that for me anything no longer meant worker. This was already a dirty word. It meant almost nothing to me. It meant to keep living the shitty life I had lived up to that moment. What did I care about work, which I had never liked and had never cared about? And what was I supposed to make of work if it didn’t even bring me enough money to get by comfortably? Now I understood everything, I had experimented with all the possible ways of living. First I wanted to be inside, then I understood that inside the system I would always have to pay. For whatever kind of life, there was always a price to pay.

Whatever you want to do, if you want to buy a car or a suit, you have to work extra, you have to do overtime. You can’t have a coffee or go to the movies. In a system, a world where the scope is only to work and produce goods. Anything you want to get from this system you have to put back. But really, physically, from yourself. I’d understood this. So the only way to get everything, to satisfy your needs and desires without destroying yourself, was to destroy this system of work for the bosses as it functioned. And above all to destroy it here at Fiat, in this huge factory, with so many workers. This is capital’s weak link, because if Fiat stops, everything else goes into crisis, everything blows up.

I got to the bar and found lots of comrades waiting for me. We all embraced, celebrating what we’d done. All Mirafiori had stopped, even the 500 lines. Production had stopped completely on the second shift. Even though the union had shut down the struggle in Maintenance, with laughable results. One by one the others arrived, the students arrived, other workers I had never seen who had been in the struggle arrived. Everyone spoke and it was decided that the strike should continue tomorrow.

Even the workers from the big automatic lathes wanted to try to strike the next day. They decide that workers from the second shift would wait in the factory for workers from the third shift, and the third shift would wait for the first. They say they want to march in the factory to shut down other workshops. Workers from the Mechanical lines want to strike for the whole shift. There is a long discussion. It’s decided to let the strike go ahead for the first shift tomorrow, from 7.30 until 11. The demands: refusal of the schedules, refusal of categories, large wage increases, the same for everyone. We want less work and more money, we write in large print on the leaflet that is made to hand out tomorrow at the gates.

And I finally had the satisfaction of discovering that the things I had thought for years, the whole time I’d worked, the things that I believed only I thought, everyone thought, and that we were really all the same. What difference was there between me and another worker? What difference could there be? Maybe he was heavier, taller or shorter, wore a different coloured suit, or I don’t know what.

But the thing that wasn’t different was our will, our logic, our discovery that work is the only enemy, the only sickness. It was the hate that we all felt for work and the bosses who made us do it. That’s why we were all so pissed off, that’s why when we weren’t on strike we were all on sick leave, to escape that prison where they took away our freedom and our strength, day after day. I finally saw that what I had thought on my own for a long time was what everyone thought and said. And I saw that my own struggle against work was a struggle we could all have together and win.

Sometimes you don’t understand each other and you don’t agree because one person is used to thinking one way and someone else in a different way. One person like a Christian, another like a lumpenproletarian, another like a bourgeois. But in the end, in the fact of having been in a struggle together, we were able to speak the same language, to find that we all had the same needs. And these needs made us all equal in the struggle, because we all had to struggle for the same things. The meeting was fantastic, it stirred us up. Everyone recounted what had happened on the line. Because nobody could know everything that happened in that factory, where there are twenty thousand workers just in the body plant.