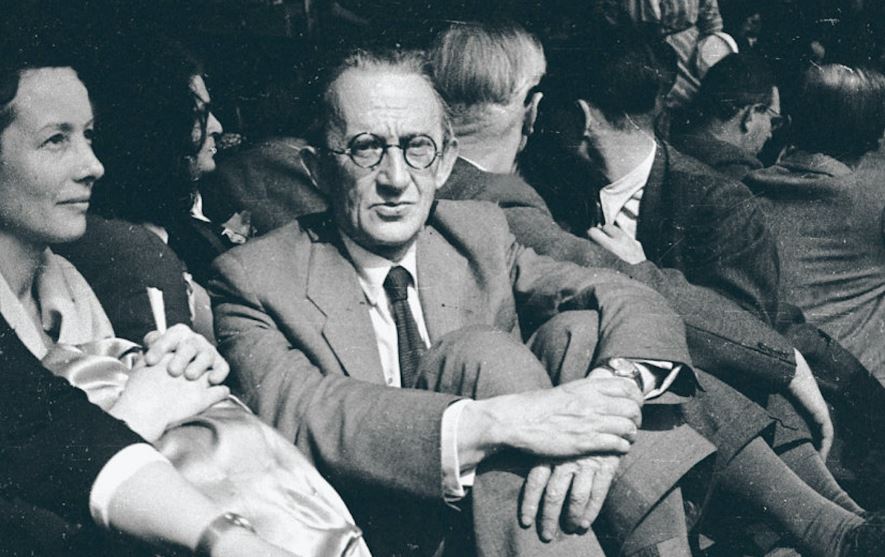

Georg Lukács: the final interview

We publish here the text of one of the last interviews with Georges Lukács, given to Hungarian television. The interview was prepared and conducted by András Kovács. Lukács talks about his youth and the influence Lenin had on his own development as a revolutionary activist. His aim is to convey the sense of Lenin’s grasp on the richness and complexity of historical reality. The interview was recorded in October 1969. We are publishing here the first part, which is mainly about Lukács’s relationship with Lenin’s thought and action.

Originally published in La Nouvelle Critique 65, June-July 1973, pp. 57-64.

I had only one personal contact with Lenin, on the occasion of the Third Congress of the Comintern,[1] where I was a delegate of the Hungarian party and introduced to Lenin as such. It should not be forgotten that 1921 was the year of Lenin’s first struggle against the sectarian currents developing in the Comintern. And as I belonged to the sectarian fraction – you can’t really call it a fraction, let’s say ‘group’ – Lenin had a rejectionist attitude towards me, as he generally had towards all sectarians. It does not even occur to me to compare my personality with that of a Bordiga,[2] who represented sectarianism in the big Italian party, or with the Fischer-Maslow group,[3] who represented the German party. Lenin obviously did not give so much importance to an official of the illegal Hungarian party.

Only in one case, when I took a stand against the participation of the Communists in parliament, in the Vienna journal Kommunismus, did Lenin refer in an article – which, please note, was directed mainly against Béla Kun[4] – to the fact that I had written a very radical and anti-Marxist article on this subject. This opinion of Lenin was very instructive for me. At about the same time, he published his book Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder, in which he dealt with the question of parliamentarianism and put forward the idea that parliamentarianism, seen from the point of view of world history, is a past stage. This does not mean, however, that the backwardness of historical development makes it possible to ignore the tactic of parliamentarism. This was a great lesson for me, which erased from my memory, or rather fully justified those lines – how can I put it? – of disparagement that Lenin wrote about me.

In addition to this episode, I was introduced to Lenin once, and we exchanged a few pleasantries during an interval of the congress.

It should not be forgotten that this congress was attended by a few hundred people, of whom only twenty or thirty really interested Lenin. He therefore showed the greater part of the delegates official courtesy and nothing more. My personal contacts with Lenin were limited to that. More important is the fact that, as a delegate, I had plenty of time to observe Lenin.

I will take the liberty of reporting a small but significant episode. At that time, the congress presidium had nothing like the importance that it does today. There was no protocol and no big podium for the members of the presidium, just a kind of small stage, like in lecture halls in university or schools. Four or five people sat around a table and constituted the presidency for this meeting. When Lenin entered, the members of the presidium rose to make room for him at the table. Lenin then waved his hand to say ‘remain seated’. He himself sat down on a step of the platform, took his notebook from his pocket and began to take notes on the presentations of the rapporteurs. He stayed seated on this platform until the end of the meeting. This episode, if we compare it with the way things turned out afterwards, I remember it as extraordinarily typical of Lenin.

When did you first hear about Lenin?

Very late. You mustn’t forget that, before the Hungarian Soviet Republic, I was not part of the workers’ movement, I had never been a member of the Social Democratic Party. It was in December 1918 that I joined the Communist Party, the first party I had ever joined.

So you were a founding member of the party?

No, no, no. I joined the party about four weeks after the meeting where it was founded. Things are like that; although I was not a socialist, I naturally knew the French and English ideologues in broad outline. I had read Kautsky, Mehring and above all the Frenchman Sorel,[5] to whom Ervin Szabó[6] had drawn my attention. But we knew nothing of the Russian workers’ movement, at most some of Plekhanov’s works.[7]

Lenin’s name began to mean something to me when I read about the role he had played in the 1917 revolution. But the real importance of Lenin I was able to assess only during my emigration in Vienna.[8]

Let me repeat that I consider it a legend that our soldiers returning from Russia in 1918 had the opportunity to get to know Lenin well. Béla Kun himself, the best-prepared ideologue, with whom in the early years I had a really good personal relationship, spoke to me much more about Bukharin[9] in our private conversations, as an ideologue, than Lenin. It was only during my studies in Vienna that I realised the significance of Lenin as a guide and inspirer of the workers’ movement.

What was it about Lenin’s behaviour that made the strongest impression on you, his contemporary?

The fact that he was a revolutionary of a completely new type. During the transformation, of course, a lot of people in the workers’ movement moved from right to left, carrying with them all those right-wing characteristics with which they had previously adapted to bourgeois society. I was not interested in this type of people. What interested me was a certain type of ascetic revolutionary to whom I felt intellectually close, and that had already developed in the French Revolution in the Jacobinism of Robespierre’s circle.[10] This type of revolutionary found its exemplary representative in Eugen Leviné,[11] executed in Munich after the fall of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, who said: ‘We Communists are dead men on leave.’

Even in Hungary, this type of revolutionary had illustrious representatives. I don’t want to list them, I’ll just mention Ottó Corvin[12] who was the typical representative of such ascetic revolutionism.

Lenin, on the other hand, represented a completely new type: one could say that he threw himself wholeheartedly into revolution and lived only in revolution, but without asceticism. Lenin was a man who knew how to accept all his contradictions, and one can even say that he knew how to enjoy life. He was a man who carried out his own actions as objectively as if he had been an ascetic, without bearing the slightest trace of asceticism. Thus, no sooner had I formed this idea of Lenin than, observing the peculiarities of his behaviour, I realised how, at bottom, this is the great human type of the socialist revolutionary. This is, of course, deeply correlated with ideological questions, whereas, in the older workers’ movement, an abstract separation between life and ideology prevailed.

On the one hand, social democracy turned Marxism into a kind of sociology, asserting the priority of economic life over the classes that derive from it, and seeing in classes an inextricable, entirely objective and sociologically general reality. Lenin rejected both hypotheses at the same time. It was he who, starting from Marx, for the first time seriously considered the subjective factor of revolution.

Lenin’s definition is well known, according to which a revolutionary situation is characterised by the fact that the ruling classes can no longer govern in the old way, while the oppressed classes are no longer willing to live in the old way. Lenin’s successors took up the concept with a certain difference, interpreting ‘no longer willing’ to mean that economic development transforms the oppressed into revolutionaries almost automatically. Lenin was aware that this problem is very dialectical, in other words a social tendency with many possible directions.

Let me clarify this attitude of Lenin through a very significant example. In the midst of the discussions surrounding the revolution of 7 November 1917, Zinoviev[13] wrote, among other things, that there was no real revolutionary situation because there were very strong reactionary currents among the oppressed masses, some of them even adhering to the Black Hundreds,[14] i.e., the Russian far right. Lenin, with his usual acuity, rejected this view of Zinoviev.

According to Lenin, when a great social crisis arises, that is, whenever people are no longer willing to live in the same way, this ‘unwillingness’ can arise, and even cannot fail to arise, in both a revolutionary and a reactionary way. Moreover, he argued against Zinoviev, a revolutionary situation would not even be possible if there were not masses who turned in a reactionary direction and thus put the subjective factor on the agenda. The task of our party was precisely to bring out the possibilities of the subjective factor in such circumstances.

It was not by chance that Lenin saw as completely erroneous the anarchist conception that the movement of individuals from capitalist egoism to socialist socialisation is the condition for revolution. Lenin always said that the socialist revolution must be made with the people that capitalism has produced and who have been damaged in various ways by capitalism. That is to say, Lenin had a type of realism that brought the various individual actions into harmony with social necessities. From this real harmonisation, Lenin sought to make the tasks of the revolution ever more tangible, so that, taking as a basis the Leninist definition that one must do is to analyse the concrete situation concretely, this concrete analysis also includes the analysis of individuals.

All this also concerns isolated individuals; therefore...

Here we can see a clear difference between Lenin’s time and his successors, for it was after his death that this difference became apparent, finally emerging in the so-called ‘great trials’ of the years 1936-38. According to such a praxis, anyone who was against the line of the central committee could be shown to have been already in their youth an element of most violent reaction.

In this way, monolithically reactionary personalities were created. Lenin had a diametrically opposed attitude. For him, objectivity of judgement was absolutely independent of personal sympathies. For example, he was very sympathetic to Bukharin personally, and emphasised his legitimate popularity in the party. But, in his so-called testament, he added that Bukharin had never been a true Marxist.

At another point, during a conversation with Gorky,[15] he emphasised Trotsky’s enormous merits in 1917 and during the civil war, and said that the party could legitimately be proud of Trotsky’s abilities and actions; however, he added (as Gorky put it: ‘a little superciliously’) that despite this, negative phenomena were also manifesting themselves here. In Lenin’s words, ‘Trotsky walks with us, but is really not part of us. In Trotsky there are certain deplorable characteristics that make him resemble Lassalle.’[16]

These two examples show very well that Lenin knew how to view fairly all the people who belonged to the close circle of his direct collaborators, that he knew how to grasp their merits and their errors concretely, considering them as they were, without the sympathy or antipathy that he himself keenly experienced being allowed to influence his political actions.

Lenin had this methodologically complex way of acting towards every person with whom he had intense contact (true at the most, of course, for some hundred or two hundred people, since it would have been inconceivable to have personal contact with every citizen of the Soviet Union or with every member of the Communist movement), and at the same time he saw the contradiction involved. For example, Lenin saw clearly how, in a civil war, it is impossible in extreme situations to behave always according to justice and law.

Once, with his characteristic sharpness, he said to Gorky, who was complaining to him about a brawl in a tavern: ‘Who could say what slap is necessary and what slap is superfluous to bring about a brawl?’ But he added: ‘It is very important that the head of the organisation fighting the counter-revolution, Dzerzhinsky,[17] should be very sensitive to the facts and to justice’; that is to say, every problem always presents itself in a complicated way, in a dialectical multilaterality, both when it is a question of a major political decision and when it is a judgement to be made of individuals.

What was the relationship between Lenin and Gorky?

Here, too, we can see that Lenin highly esteemed Gorky’s abilities, as is apparent from his letters; but we can also see that he blamed Gorky harshly when the writer took a wrong turn. Once again, we see that Lenin was very far from the concept that there are individuals who are completely devoid of error and, vice versa, individuals who are error incarnate.

In his book on Left-Wing Communism,[18] when talking about mistakes, Lenin made it very clear that people without faults do not exist. Lenin says that an intelligent person is one who does not make fundamental mistakes and corrects those they do make as quickly as possible. We can also see here that, when Lenin demanded a concrete analysis of the concrete situation, he always included also human and political contacts with important people.

Lenin’s relationship with Martov[19] is very interesting. When two opponents...

This is very interesting because it existed from the very beginning of the century, when both were still in the illegal movement and in continual discussion; in spite of everything Lenin liked Martov very much, and in spite of all the differences he held him to be good and honest. Lenin demonstrated this clearly when, after the peace of Brest-Litovsk[20] and the civil war, class struggles became more acute. Rather than taking action against Martov, but did everything possible to get Martov to leave the Soviet Union and deploy his activity abroad.

Lenin wanted to remove Martov from the Russian labour movement, but did not want to eliminate him physically. This attitude is clearly different from what happened in the years to come.

I think this was part of Lenin’s realism. As he said: ‘Better an émigré enemy than a martyr in one’s own country.’

That is also Lenin. How to put it... It has its origin in his anti-ascetic realism. As I mentioned earlier, Lenin did not reject the idea that in civil war innocent people also die. However, he sought to minimise these consequences, when this was compatible with the interests of the revolution, and when the slightest possibility existed he did not use extreme means against people.

I think that his relationship with Gorky, apart from what can be drawn from it from a human point of view, is also interesting as a relationship between a politician and a writer, and – beyond that – a relationship between politics and literature.

That is absolutely right. In this sense, and that is very interesting, there is a certain analogy with Marx, who loved and esteemed Heine[21] very much, even though he was clearly aware of his negative moral behaviour on several counts. It was exactly the same with Lenin, who rightly considered Gorky the greatest living Russian writer. This was reflected above all in a very personal sympathy. It must be said, however, that Gorky was not the only writer for whom Lenin felt sympathy. Indeed, if you refer to notes written during the period of the civil war, Lenin speaks with great irony, but with recognition of his talent, of a writer who was clearly counter-revolutionary. Excuse me, but his name does not come to my mind, as he was not an important writer. But let me add – and this is far more important – that Krupskaya[22] was quite right when she said that in the article written in 1905,[23] which later became the touchstone of ‘how to do literature’ in the Stalin period, Lenin did not think in the least that the positions he set out there were applicable to literature: they were only applicable to the new direction that the press and party publications had to take after emerging from illegality.

Of course, Lenin was quite right when he said that the party press should have a certain line and that a political article should be written along a certain line. But this has absolutely nothing to do with literature. Lenin never thought that the literature should become the official organ of socialism. This can be explained on two grounds. On the one hand, Lenin had no regard for so-called official literature, which he did not consider to be real literature at all; on the other hand, he was strongly opposed to the so-called literary revolution.

It is well known that Lenin regarded even Mayakovsky[24] with a certain scepticism. Once, speaking at a Komsomol meeting, he said that he remained with Pushkin, whom he regarded as a true poet. But this does not only concern recognition of the freedom necessary for literature (of course, as long as this freedom does not mean counter-revolutionary propaganda, which Lenin would obviously have fought, literary or not); it also meant condemnation of the conception which had developed in the Soviet Union with Proletkult,[25] represented here by Kassak and his group around 1919. And it was also rejection of the tendency, part of Italian Futurism, according to which revolutionary literature should be radically new and condemn works of old literature to the museum or to destruction.

About Proletkult, Lenin said that the strength of Marxism lay precisely in the fact that it succeeds in making its own every authentic value that manifests itself in the millennial development of humanity. In saying this, he was simply following the line of Marx: we know that Marx referred to Homer as the greatest poet of ‘the childhood of humanity’.

If we analyse Lenin’s relationship with Tolstoy,[26] we realise – in contrast to Plekhanov and the others who had a thousand criticisms of Tolstoy – that Lenin knew how to grasp what was substantial in him – his profound democratic sense. I would like to quote a passage Lenin wrote to Gorky, where he says, among other things, that before the birth of Tolstoy there was not a single true peasant in Russian literature.

Did this tolerance concern only art, literature, or also ideological action in general – not of course that which is in permanent contact with politics, like the press?

Lenin had a double point of view, which again expresses a real dialectic. For example, he always recognised every result of the natural sciences, rejecting the idea that Marxism could correct the natural sciences by seeing itself as their successor. However, he was well aware that science is an important ideological factor, so he fought against the idealism that was resurfacing in the modern natural sciences, but he did so in such a way as not to undermine the valid claims of natural science.

In the period that he was writing Materialism and Empirio-Criticism[27] the new discoveries of modern physics had come to light, which according to Lenin must be fully accepted when they are correct (for example the formulae of the atom). But what really matters is to establish whether the conception of the atom exists independently of human consciousness – as Marxist philosophy asserts – or whether it is the product of this. This second hypothesis, which is no longer a hypothesis of the natural sciences, but arises from a philosophical development or orientation of the natural sciences, was rejected by Lenin in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism as an idealist conception. He reaffirmed such a rejection later on. But, for Lenin, this never meant directing the discoveries of the natural sciences in the name of Marxism.

Does all this concern the social sciences as well?

In my opinion, it does not concern the social sciences. Marx carried out a revolution in the social sciences which cannot be repeated. It should not be forgotten that similar revolutions have also occurred in the natural sciences. One thinks of the epoch of Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo. Indeed, one cannot call freedom of the natural sciences such statements as: ‘It depends on how I see it whether the earth revolves around the sun or the sun revolves around the earth’. The fact is that Galileo confirmed without any doubt that it is the earth that revolves around the sun.

Lenin rightly regarded Marxism as a discovery of this type, which one cannot fail to take into account if one wants to be taken seriously in scientific terms. That is why – quite naturally – it would never have occurred to him to allow Böhm-Bawerk[28] or other anti-Marxist economic theories to be taught in a socialist university. But this does not concern the culture of society in a broader sense.

Lenin did indeed recognise the validity of philosophers, writers and ‘men of letters’ who were not Marxists at all. Once again, we can see in Lenin this concrete dialectic of what is correct and what is not, in terms of which there is no general rule from which we can deduce, for example, that such and such a professor has or does not have the right to occupy their chair.

That is true. But I believe that in ideological research, and therefore also in research in the social sciences, one must have the possibility of making assumptions that may turn out to be inaccurate later on.

Lenin never regarded Marxism as a collection of dogmas valid once and for all, but as the first accurate theory of society, developed in close connection with social development, for which, as there has been development, there can also be regression. In all development there is this double character, recognised by Marx, by Engels and by Lenin. He only demanded that the correctness of the theory be verified in the ideological struggle. It is indeed natural that Lenin’s dual view does not mean admitting that two hypotheses are both equally right or equally wrong.

Lenin gave a great deal of space to discussion because he knew that, around a given concrete question, there can only be one truth, whereas what the so-called reformists maintain today, based on a pluralist hypothesis, is naturally ridiculous, and shows a confusion on their part between two completely different things. The fact that there may be a situation in which research and discussion may even last twenty years, does not mean that the truth can be double or triple: the truth is one.

So, one could say that the road to truth is not unique...

It is neither unique nor unitary. Lenin himself, on an important question, accepted a completely new situation in relation to Marx. It should not be forgotten that Marx had conceived the transition from capitalism to socialism in a very rigorous sense: this change would occur first in the most developed countries. On this point, Lenin put forward his own conception. The question of socialism arose in an underdeveloped country, and Lenin opted for the socialist situation, i.e. – and let me give my own interpretation here – Lenin decided according to the necessity of this given historical situation.

I mean that, in 1917 in Russia, there were two huge mass revolutionary movements. One was the protest of the whole people against the imperialist war, the other represented the age-old demand of the peasants to share the large landholdings and work their own land. If we analyse these two situations abstractly, neither of these demands is socialist in the narrow sense of the word. Even a bourgeois state can make peace. It can also redistribute the land.

However, at that time, not only the bourgeois parties, but also popular parties such as the Socialist-Revolutionary Party,[29] and the Mensheviks among the workers’ parties, were both against an immediate peace that would put an end to the imperialist war, and at the same time rejected by all means the full redistribution of land. For Lenin, it was clear at that point that only a socialist revolution could satisfy the aspirations of hundreds of millions of people. This is why, in an underdeveloped Russia, Lenin was not concerned with making the October Revolution on the basis of abstract tactics, but on the basis of a concrete analysis of the concrete situation that existed in Russia in 1917.

Lenin’s patience with the diversity of individuals and aspirations has often been recalled. Do you think that patience is an important element in the revolutionary attitude, even though at first sight patience seems to contradict the concept of revolution?

That is also a question of dialectics. In Lenin there was this dialectical unity of patience and impatience, thanks to which he decided on the direction to take according to the concrete analysis of the concrete situation.

I would like to show this characteristic of his through two examples. After 1905, it was quite clear to Lenin that the revolution had been defeated and that a period of counter-revolution was beginning. This fact is connected with the question of elections and the conflict with the Bogdanov-Lunacharsky faction. That did not just concern minor issues but also the events of 1917.

When, during the summer of 1917, the Petrograd workers were very agitated and wanted to hold a big demonstration, Lenin declared himself against the demonstration, because he knew that, with the existing balance of power, it would have meant a direct and catastrophic confrontation between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie with its supporting strata. It is well known that this demonstration took place against Lenin’s will and that it acquired the character of a civil war, but it is also well known that the proletariat was then defeated and that Lenin was forced to retreat to illegality. However, after the failure of Kornilov’s coup d’état,[30] the revolutionary upsurge was extraordinary.

This phenomenon was expressed by Lenin in two ways. On the one hand, if I remember correctly, he wrote an article in September in which he invited the majority of Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks in the soviets to take power, promising them that, insofar as they proceeded to socialist reforms, the Communist Party would be a loyal opposition. A few days later, he wrote another article, in which he said that this situation had lasted only a few days, but was now over.

Then came October, and Lenin, with the same violence and impatience with which he had opposed the July demonstration, demanded the immediate assumption of power. For a long time, he broke off relations with his oldest and most intimate comrades such as Kamenev[31] and Zinoviev because they did not share his point of view. This means that Lenin was patient in July but not in October, taking into account the objective and subjective factors of the revolution. So, here again, we find the second point: it is always the concrete analysis of the concrete situation that decides.

I am thinking of what was said about Lájos Nagy,[32] this impatience...

In 1934 a writers’ congress[33] was held in Moscow, in which Lájos Nagy also participated. I was on good terms with him, and he came to me and asked me how long I thought Hitler’s rule would last. I told him I was not a prophet, but that as far as I could predict, it would last ten to fifteen years. Then Nagy was overcome with rage; he went red and struck his fist on the table, shouting that since he had a different idea, because revolution would have broken out long before, he was not a good Communist like me. That is also impatience.

Let me illustrate the question of impatience with another example. In Moscow, the big demonstrations were very badly organised, so, if the workers of a factory or an institute were to march on Red Square at one o’clock in the afternoon, the order to assemble somewhere was given for six o’clock in the morning. That also happened to me during a demonstration. I happened to be walking next to a very good woman who had emigrated to Russia in 1919. As we were walking, the Kremlin towers suddenly appeared. The woman was very enthusiastic and exclaimed: ‘You see, it was worth assembling at six in the morning to see all this!’ I answered her in exactly the opposite way from what I had told Lájos Nagy: ‘If Lenin had had your patience, the Bolsheviks would never have moved into the Kremlin.’

I don’t know whether these two anecdotes show that patience and impatience are not two mutually exclusive metaphysical opposites, but that the same person must be – and again I would like to remind you of Lenin’s concrete analysis of the concrete situation – patient and impatient at the same time.

In recent years, the question arises as to what revolutionary behaviour actually is in relation to some very different events. Let us say, to speak generally, in a certain way with the Western student movements, and at the same time in the socialist countries: how is it possible to be revolutionary in a country where the revolutionary forces are in power and where they therefore have very different tasks? As someone who has seen yourself as a revolutionary for over fifty years, what can you say about this?

Let’s look at the student movements. I study and observe these movements with great sympathy because, if I compare the situation in 1945 with today, it really seemed then that the ‘American way of life’, that is, manipulated capitalism, was completely victorious even on the ideological level. Now at least one layer is beginning to move, even if not quite consciously, and it is unimportant if it does not use the right means.

Allow me a paradox: when modern capitalism was born after primitive accumulation, workers instinctively felt they were being degraded by the machine. This feeling was at the origin of ‘Luddism’, i.e. the destruction of machines. The destruction of machines cannot be considered a correct tactic. However, this was undoubtedly a necessary step, which later led the workers to organise themselves in trade unions. Today, I see the students not as models of revolutionary action, but as initiators of a movement in world history. And I don’t care whether the leaders of the student movements see it that way or not: objectively, behind all this, is the fact, as they say, that they ‘don’t want to become manipulated professional idiots’, and that is why they are looking for another way. They haven’t found it yet, and they won’t find it as long as wider layers of people are not able to revolt against this manipulated capitalism.

We see the beginnings of this revolt in very primitive forms in America and elsewhere in the anti-war movements. We can see it in the Black question and in the discussion that has arisen around it. So, we can say that we are at the initial stage of a revolutionary revolt against manipulated capitalism which corresponds, for example – but we have to be careful here because in history things don’t repeat themselves – to the emergence of the workers’ movement between the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century. At that time, Marxism was not yet spoken of, but without it Marxism would never have been born.

If we come back to our situation today, I would say that socialism finds itself facing a great new problem. Lenin was the last great figure of a possible new development, which then became more and more impossible. Let us not forget that at the beginning of the workers’ movement, if we think only of the great figures of Marx, Engels and Lenin, we see how the great ideologue and the great political leader were united in one person. They coexisted in each of these three figures. And the same should have been true of Lenin’s successor, Stalin. I believe that Stalin was a convinced revolutionary, if one applies an objective historical judgment to him. He was a highly intelligent man of great talent, an extraordinary tactician, but I would say devoid of any ideological sensitivity.

In numerous essays, which I cannot go into here, I have written that in the period of Marx and Lenin the whole worldwide movement had a strongly defined ideological conception, from which the workers’ movements of the different countries derived their strategy, and tactical decisions were made within this framework. In the Stalinist period, the party leader was at the same time the competent ideologue of the party, and – as we know – competent in everything: this is how a Rakosi, a Novotny[34] and so on were born.

We must be aware that there is little chance that the workers’ movement will have a new Marx, a new Engels or a new Lenin. Hence, the new problem of what the relationship between ideological training and party political tactics should be. In my opinion, this problem has not been solved.

What possibilities do you think there are for someone who wants to act today?

Of course, there are no great possibilities for someone who wants to act. However, there is no period in which one cannot do something. For example, there is no obstacle whatsoever to those who are inclined to theoretical and ideological studies devoting themselves to ideological research and exerting their influence through it, always bearing in mind all the difficulties and dangers of deviation. In this respect, it is only necessary to recognise in the West that manipulated capitalism does not represent a new era that is neither capitalist nor socialist, but that there is simply a phenomenon to be analysed.

On the other hand – and I attach great importance to this point, as I always have – it is necessary to be clearly aware that in a great number of essential questions Stalin was not the successor of Lenin, but his opposite. In this sense, from the human point of view, one of the most important problems is to return to Lenin’s revolutionary type. That is why I consider it so important to see Lenin as a real man and not a legendary figure. Today this has above all a great current political significance.

Translated by David Fernbach

[1] The Third Congress of the Communist International was held in Moscow from 22 June to 12 July 1921 with the participation of 605 delegates, representing 103 organisations and 52 countries. Its context was marked, among other things, by the introduction of the NEP in Soviet Russia, the world economic crisis and Lenin’s struggle against ‘leftism’, in the context of the debates on the formation, organisation and orientation of the young Communist parties.

[2] Amadeo Bordiga (1899-1970), a member of the left wing of the Italian Socialist Party, participated in the foundation of the Italian Communist Party in 1921 and became one of its leaders. Opposed to the united front tactics developed by the Comintern, he was excluded from the PCI leadership in 1926. Critical of Stalin, he was then excluded from the party in 1930. Leader and main theoretician of the Internationalist Communist Party (1944-66).

[3] Ruth Fischer, née Elfriede Eisler (1895-1961). Joined Austrian Social-Democratic Party in 1914, then participated in the foundation of the Austrian Communist Party in 1918. Left Austria for Berlin in 1919 and joined the left wing of the KPD. Member of the KPD leadership with Maslow from 1924 to 1925, she was expelled in 1927 and founded the oppositional communist group Leninbund. Emigrated to France when the Nazis came to power in 1933. Arkadi Maslow, pseudonym of Isaak Yefimowich Chemerinsky (1891-1941), born in Germany of Russian parents. Joined the KPD on its foundation in 1919, later led its left wing with Ruth Fischer. Member of the KPD leadership (1924-25), he was expelled from the party in 1927 for his closeness to the anti-Stalinist Left Opposition. Emigrated to France in 1933 and then to Cuba.

[4] Béla Kun (1886-1939), Hungarian journalist and Communist leader. Joined the Social-Democratic Party in Hungary at a very young age (1903). Mobilised in 1914, he was taken prisoner by the Russian army and joined the Bolsheviks during his captivity. Back in his country, he founded the Hungarian Communist Party in December 1918 and became president of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After its fall (August 1919), he took refuge in Vienna and then in the USSR where he took part in the civil war. From 1921 onwards, he played an important role in the Communist International: a member of its executive committee (1921), then of its presidium (1926). He supported Stalin against the Left and Right Oppositions, but later opposed the Popular Front orientation. Arrested in 1938 and probably executed in 1939.

[5] Karl Kautsky (1854-1938), reformist-centrist leader and theoretician of German Social Democracy and the Second International. Editor-in-chief of the theoretical journal Neue Zeit (1883-1917). Franz Mehring (1846-1919) journalist, historian and Marxist philosopher. Member of the SPD since 1891, one of the theoreticians of its left wing. He opposed the social-patriotism of the SPD majority in August 1914. In 1916, together with Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Karl Liebknecht, he founded the radical, anti-war left wing of the SPD later known as the Spartakus group. At the end of 1918, one of the founders of the German Communist Party. Georges Eugène Sorel (1847-1922), French socialist theorist with contradictory intellectual influences, he was initially a supporter of revolutionary syndicalism and opposed social-democratic opportunism. After 1909, he broke with syndicalism and joined a Catholic-Monarchist movement. This did not prevent him from supporting the October Revolution in 1917.

[6] Ervin Szabó, pseudonym of Samuel Armin Schlesinger (1877-1918), Hungarian libertarian-Marxist theorist, librarian and library director, translator of Marx and active in the anarcho-syndicalist movement.

[7] Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (1856-1918). After being a populist from 1876 to 1880, helped introduce Marxism in Russia. Founded the Liberation of Labour group (1883). Member of the bureau of the Second International in 1889. Participated in the foundation of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Russia (1898) and collaborated with Lenin in the editing of its newspaper, Iskra. Initially supported the Bolsheviks, then the Mensheviks. In 1914, called for the defeat of Germany. Returned to Russia in March 1917, supported the provisional government and opposed the Bolsheviks.

[8] After the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in August 1919, Lukács took refuge in Vienna, where he lived for most of the 1920s and wrote his major philosophical work, History and Class Consciousness.

[9] Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (1888-1938), journalist and Marxist theoretician. Bolshevik since 1906. Arrested and deported in 1910, he escaped and emigrated to Austria-Hungary, then to Switzerland, Sweden and the United States. Left-wing Communist, opposed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918, and later moved to the right. Member of the of CPSU central committee (1917-34) and of its political bureau (1924-29), member of the presidium of the executive committee of the Third International (1919-29) and its president (1926-29). Editor-in-Chief of Pravda (1917-29) and of Izvestia (1934-37). Allied with Stalin against the Left Opposition (1923), then led the Right Opposition with Rykov and Tomsky (1928-29) before capitulating. Arrested in 1937 and executed in 1938.

[10] Maximilian Robespierre (1758-1794), historical figure of the French Revolution, leader of the left-wing Jacobins and head of government (1793-94). Deposed by a counter-revolutionary coup d’état on 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794) and beheaded.

[11] Eugen Leviné (1881-1919), Russian Jew, studied in Berlin where he joined the SPD, then the Spartakusbund in 1916 and the German Communist Party on its foundation. During the German Revolution of November 1918, he headed the Neukölln workers’ council. He participated in the creation of a red army in the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic (April-May 1919) and, after its fall, was condemned for high treason and shot.

[12] Ottó Korvin, pseudonym of Ottó Klein (1894-1919), bank employee and poet, he became a Marxist in 1917 and participated in the foundation of the Hungarian Communist Party (end of 1918), of which he became a member of its central committee and its treasurer. During the Hungarian Soviet Republic, he was in charge of the political department of the people’s commissariat for internal affairs and a member of its central executive committee. After the fall of the Soviet Republic, he remained in Hungary to organise the Communist Party underground, but was arrested and executed.

[13] Grigory Zinoviev, pseudonym of Hirsh Apfelbaum (1883-1936); Bolshevik leader, friend of Lenin. Joined the Russian Social-Democratic Party in 1901 and its Bolshevik fraction in 1903. Participated in the 1905 revolution in St Petersburg, then lived in exile with Lenin until the February Revolution of 1917. After the October Revolution, main party leader in Petrograd, member of the political bureau (1921-26) and president of the Third International (1919-26). After Lenin’s death (1924), he allied himself with Stalin and Kamenev against Trotsky, then with the latter against Stalin and Bukharin (1926-27). Excluded from the party, he capitulated in 1928 and was partially rehabilitated before being excluded again in 1932. After the assassination of Kirov (1934), he was imprisoned, condemned and executed (1936).

[14] The ‘Black Hundreds’ were an ultra-reactionary far-right terrorist group in tsarist Russia responsible for anti-Semitic pogroms and attacks against revolutionaries with the complicity of the authorities.

[15] Maxim Gorky, pen name of Alexis Maximovich Peshkov (1868-1936), realist writer, editor and playwright. Had a wretched childhood and worked in many jobs before becoming a journalist and writer in the early 1890s. Initially close to the populists, he later supported the Russian Social-Democratic Party (RSDLP) and its Bolshevik faction. Actively participated in the 1905 revolution. Arrested and then released by an international campaign, he went into exile, first in the United States, then in Italy until his return to Russia in 1913 under an amnesty. Participated in the 5th Congress of the RSDLP in London (1907) where he met Lenin. Organised a school for workers’ cadres in Capri with Bogdanov and Lunacharsky (1909). After the October Revolution, at first fiercely opposed the Bolsheviks before supporting them critically following the assassination attempt on Lenin in the summer of 1918. Suffering from illness, he left Russia in 1921 and settled again in a semi-exile in Italy (1923). He returned periodically to the USSR from 1927 and settled there permanently in 1932, showered with honours by Stalin. He sang the praises of the regime and played a central role in the creation of Soviet literature and ‘socialist realism’. He officially died of pneumonia in June 1936, though some historians suggest the possibility of poisoning.

[16] In the original version of this text by Gorky, published in 1924, Lenin makes no criticism of Trotsky or any reference to his ‘Lassalle’ side. On the contrary, it is full of praise: ‘“Many false things are said about my relations with him. Yes, many false things are said, especially about me and Trotsky.” Banging on the table, he declared:

“Let me be shown another man capable of organising an almost exemplary army in one year and of winning the esteem of military specialists. We have this man. We have everything. And we will also do wonders”’: Maxim Gorky, Lénine et le paysan russe (Paris: Éditions du Sagittaire, 1924), pp. 95-6. It was only in later versions, from 1930 onwards, after Stalin’s victory in the struggle for the party leadership, Trotsky’s expulsion from the country and the writer’s return to the USSR with great pomp and circumstance, that these critical additions suddenly appeared.

[17] Felix Dzerzhinsky (1877-1926). One of the founders of the Polish Social-Democratic Party in 1900. Spent eleven years in tsarist prisons and jails. Member of the Bolshevik Party from March 1917. Nicknamed ‘Iron Felix’ because of his inflexible and incorruptible character, he founded and chaired the Cheka (Pan-Russian Extraordinary Commission for the Repression of Counter-Revolution and Sabotage), then the GPU and finally the OGPU from 1917 to 1926. People’s commissar for internal affairs (1921-24), then for railways (1922-26). Chairman of the Supreme Economic Council (1924-26), he died of a heart attack.

[18] The book Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder was written by Lenin in April-May 1920, on the eve of the Second Congress of the Communist International. It was published in Russian in June, then in July in German, French and English for distribution to the Comintern delegates.

[19] Julius Martov (1873-1923), pseudonym of Yully Osipovich Tsederbaum; Social-Democratic activist, first close to Lenin in the group around the newspaper Iskra; after the split of 1903 leader of the Mensheviks and of their pacifist and internationalist left wing during the First World War. In exile in Switzerland when the revolution broke out, he returned to Russia in May 1917. A determined opponent of the Bolsheviks, he was allowed to emigrate to Germany in 1920.

[20] This was the peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 in the city of Brest-Litovsk (today in Belarus) between Russia and the powers of the Quadruple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Turkey), ending Russian participation in the First World War.

[21] Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), nineteenth-century German romantic writer and poet, friend of Marx and Engels.

[22] Nadezhda Konstantinova Krupskaya (1869-1939), Marxist activist since 1891, arrested and deported in 1896. Married Lenin in 1898 and was his main collaborator. Secretary of the editorial staff of Iskra, she organised its clandestine distribution network as well as the liaison of the Bolshevik leaders abroad with the sections of the party in Russia. On the eve of the First World War, together with Inessa Armand, she directed the first party journal for working women, Rabotnitsa. After the October Revolution, she devoted herself to educational issues and the management of libraries as deputy to the people’s commissar for public education, Lunacharsky. A member of the central control commission of the Bolshevik Party, she was also a member of the United Opposition until her capitulation to Stalin-Bukharin in 1927.

[23] V. I. Lenin, ‘Party Organisation and Party Literature’, 13 November 1905.

[24] Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930), futurist poet and playwright. Born in Georgia, he collaborated in 1905 with the local Social Democrats. Bolshevik from 1908. Imprisoned three times in 1908-09, he left the RSDLP after his release and became a central figure of the artistic avant-garde with the ‘Futurist’ movement that he led. Published his first poems in the early 1910s. Welcomed the October Revolution enthusiastically and put himself at the service of the new government’s agitprop through his poetry, slogans, posters and plays; actively collaborated with the soviet newspaper Izvestia. In 1923, he founded the review and communist/futurist artistic movement LEF (= left art front). Committed suicide in 1930.

[25] Proletkult (= proletarian culture) was a mass organisation for cultural education. It was founded in September 1917 as a workers’ association independent of parties, soviets or trade unions. It was led by, among others, Alexander Bogdanov, a Marxist theorist and former dissident Bolshevik leader, who believed that the working class should autonomously build its own culture, the hegemony of which would guarantee the construction of socialism. After the October Revolution, Proletkult maintained its independence from the state, but in 1920, following Lenin’s intervention, the Communist Party central committee decided to subordinate Proletkult to the people’s commissariat for public education. From then on, it began to decline and disappeared in 1932.

[26] Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828-1910), major Russian realist essayist and writer, author of War and Peace and exponent of a doctrine of non-violent social progress (‘Tolstoyism’).

[27] Materialism and Emprio-Criticism was written by Lenin in 1908 in Geneva, after extensive philosophical studies, including at the British Museum in London, and published in Russian in May 1909. It was primarily intended to counter the philosophical conceptions of his political opponents within the Bolshevik faction, first and foremost their main theoretician, Alexander Bogdanov, and his ‘empirio-critical’ theory of overcoming the conflict between idealism and materialism.

[28] Eugen Böhm-Bawerk (1851-1914), an Austrian economist, opposed the spread of Marxist ideas in his discipline by developing a subjectivist and idealist interpretation of economic laws. Founder of the Austrian ‘marginal utility’ school.

[29] Socialist-Revolutionaries, a party founded in late 1901 or early 1902 by a combination of populist groups. The Socialist-Revolutionaries considered the peasant class, without internal social distinctions, as the driving force of the revolution and the construction of socialism in a Russia where capitalism could not develop as in the West. They therefore denied the proletariat any leading role. After the February 1917 revolution, the Socialist-Revolutionaries were, with the Mensheviks and the Cadets, the main force of the bourgeois provisional government, several of its leaders becoming ministers (Kerensky, Avksentiev, Chernov). In July 1917 they split into separate Left and Right parties, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries forming a coalition with the Bolsheviks in the first soviet government from November 1917 to March 1918. The Right Socialist-Revolutionaries supported the White forces in the civil war; when the Left Socialist-Revolutionary party was banned in July 1918, many of its members joined the Communist Party.

[30] Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov (1870-1918), tsarist general. During the First World War he commanded the south-western front, appointed supreme commander-in-chief in July 1917. Attempted a military coup against the bourgeois provisional government at the end of August, and was arrested in September. Escaped in November and became commander-in-chief of the anti-Bolshevik ‘Volunteer Army’. Died in February 1918 during the assault on Ekaterinodar.

[31] Lev Borisovich Kamenev, pseudonym of Lev Rozenfeld (1883-1936). Member of the RSDLP from 1901 and Bolshevik from 1903. Member of the central committee (1917-18 and 1919-27) and of the political bureau (1919-25). Chairman of the Moscow Soviet (1918-26), Director of the Lenin Institute (1923-26). Plenipotentiary representative in Austria (1918) and Italy (1926-1927). People’s commissar for internal and external trade (1926). Member of the ‘troika’ with Stalin and Zinoviev against Trotsky, then Trotsky’s ally against Stalin and Bukharin. Excluded from the party in 1927, capitulated and reinstated in 1928 and appointed head of a publishing house before being excluded again in 1932. Director of the Gorky Institute of World Literature (1934). After the murder of Kirov (1934), arrested and executed (1936).

[32] Lajos Nagy (1883-1954), writer and journalist, joined the Hungarian Communist Party in 1945.

[33] At this congress (August-September 1934) the Union of Writers of the USSR was founded by order of Stalin’s central committee of the Communist Party, after the dissolution of all previously existing literary associations and groups. The Congress was chaired by Gorky. The Union institutionalised party control over writers and the application of ‘socialist realism’ in literature.

[34] Mátyás Rakosi, pseudonym of Mátyás Rosenfeld (1892-1971), Stalinist general secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party (renamed Hungarian Workers’ Party in 1948). Prime minister (1952-53), but removed from power in 1956, expelled from the HCP in 1962 and died in the USSR. Antonín Novotny (1904-75), member of the Czech Communist Party in 1921, general secretary in 1956 and president of Czechoslovakia from 1957 to 1968.