Embrace the Witch!

Invite these women in, and let their voices pull on you: we pick our favourite witchy quotes from The Verso Book of Feminism.

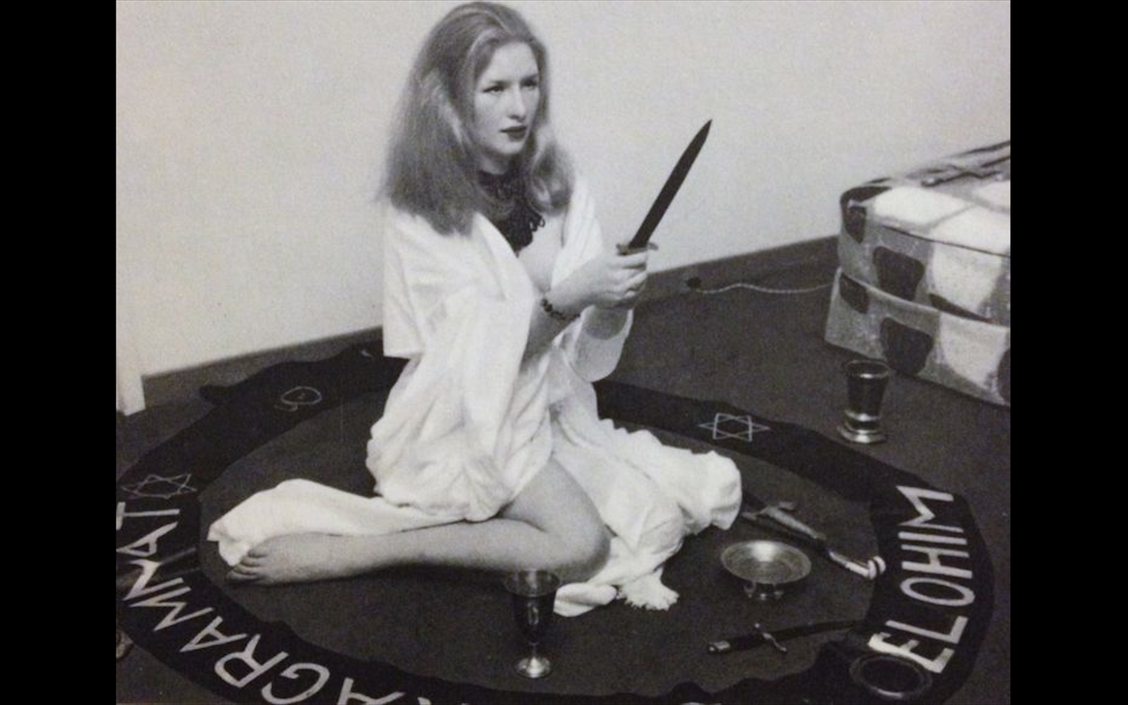

Halloween, also called Samhain the Witch’s New Year, marks the border between the light and the dark, between the bright days and the cold nights, between the dead and the living. Witches are said to traverse this space and find, in the dark, what new things can be born.

We’ve pulled six witchy selections from the Verso Book of Feminism! From the 1st century to the present, women making things and bringing new worlds to birth have been called witches; some have embraced the identity. In this way, the Book of Feminism is possibly also a grimoire. Since the veil is thin right now, invite these women in, and let their voices pull on you.

77 CE

Pliny the Elder

Naturalis Historia, XXV, 10

There was nothing more highly admired than an intimate knowledge of plants, in ancient times. It is long since the means were discovered of calculating before-hand, not only the day or the night, but the very hour even at which an eclipse of the sun or moon is to take place; and yet the greater part of the lower classes still remain firmly persuaded that these phenomena are brought about by compulsion, through the agency of herbs and enchantments, and that the knowledge of this art is confined almost exclusively to females.

The skills of Greek women—like famed second-century BCE astronomer Aglaonike from Thessaly, who was known for her expertise in predicting lunar eclipses—were considered to be magic and witchcraft rather than true scientific knowledge. Due to the circumscribed positions of women in the male-dominated Greek city-states, talented women were often known as sorceresses and priestesses rather than scholars. Aglaonike was called “the Witch of Thessaly” for her supposed talent of “making the moon disappear.” Here, Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder alludes to this history in his multivolume work Naturalis Historia.

1922

Masuda Rahman

Letter to the Newspaper Bijoli

Pack the conservative old men off to the forests with their rosaries, snatch the religious texts from the hands of the hypocrites and lawyers, drive the offenders away from the sacred podium of this temple we call society. Preach the words of our creator for the benefit of mankind… An irreligious and anti-motherhood society has decreed that women must always satisfy desires, cook delicious food, give birth to babies every year like bitches do, must abide by all its selfish dictates with bowed heads and offer their devotion, blindly, at its feet. We are goddesses, women, and vicious witches, all in one. Beware—it is not as if we have lost all sense of self-respect because we play mothers to you… My fellow workers! You are running after wealth, but where will you keep the accumulated treasure? … Our beautiful country now looks like a cremation ground—a place for evil spirits to prowl around, a ground for vultures to keep their eternal vigil. The air is putrid with the poisonous smell of decay! Is this a suitable place to erect a shrine of gold? We have to destroy, burn and erase all that is there to create anew. You cannot cleanse and purify this abhorred land, now full of waste, without our help. You work very hard to bring home the golden harvest every year, but we are the ones who do the threshing, separating the grains from the husk … Let us do the job that is ours. The flames of a hundred Vesuvius are stored in our chests, our hearts are tempestuous with the power of a thousand cyclones, and our eyes contain the unfathomable waters of ten thousand oceans.

Bengali Muslim writer Masuda Rahman was well known for her nationalist anti-British views, as well as her fierce criticism of patriarchal traditions in Islamic and Bengali culture.

1973

Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English

Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers

Women have always been healers. They were the unlicensed doctors and anatomists of Western history. They were abortionists, nurses, and counselors. They were pharmacists, cultivating healing herbs and exchanging secrets of their uses. They were midwives, travelling from home to home and village to village. For centuries women were doctors without degrees, barred from books and lectures, learning from each other, and passing on experience from neighbor to neighbor and mother to daughter. They were called “wise women” by the people, witches or charlatans by the authorities. Medicine is part of our heritage as women, our history, our birthright.

Feminists Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English wrote this pamphlet in “a blaze of anger and indignation,” part of the broader second-wave feminist activism in the United States that critiqued the sexism in medical practice and sought to teach women about their own bodies. Ehrenreich and English argued that historically, witch hunts were part of dismissing and criminalizing women’s knowledge in order to allow state-approved male doctors to take over medical care, an argument later researched and credited by feminist historians. “Our ignorance” of our own bodies, they argued, “is enforced.”

1978

Silvia Bovenschen

“The Contemporary Witch, the Historical Witch, and the Witch Myth”

Up until recently the word witch did not have a pleasant ring to it. It evoked childhood fears—we often called old teachers whom we could not stand and whom we feared by that name. The word “witch” experienced the same transformation as the word “queer” or “proletarian”: it was adopted by the person affected and used against the enemy who had introduced it … The fact that women are dressing up as witches for their demonstrations and festivals also points to this mimetic approach to their own personal history through the medium of mythological suggestion. They are, to a certain extent, practicing witchcraft. The anti-feminist metaphysics of sex kept conjuring up the magical demonic potential of femininity until this potential finally turned against it.

The second-wave women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s reclaimed the figure of the witch as an icon of women’s power, women’s rage, and a target of male fear and misogynist violence—as Bovenschen, German literary critic and feminist, notes here.

2015

Genderchangers Academy

"What Is a Genderchanger?"

A genderchanger figures out how her computer works and she is not afraid of taking it apart. She can also change any card, plugin and unplug any devices without too much hassle. She is the witch and a knitter of modern times. She is a secretary with a ballpoint of steel. She is also kind to penguins and she lets her cat sit on the monitor.

A "gender changer" is an adapter that changes the “sex” of a computer port, here repurposed by the Genderchangers Academy, a women-only organization in Amsterdam dedicated to involving women in technology.

- all of the excerpts above are taken from The Verso Book of Feminism - an unprecedented collection of feminist voices from four millennia of global history. See all our Gothic Feminist reading here.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]Throughout written history and across the world, women have protested the restrictions of gender and the limitations placed on women’s bodies and women’s lives. People—of any and no gender—have protested and theorised, penned manifestos and written poetry and songs, testified and lobbied, gone on strike and fomented revolution, quietly demanded that there is an “I” and loudly proclaimed that there is a “we.” The Verso Book of Feminism chronicles this history of defiance and tracks it around the world as it develops into a multivocal and unabashed force.

Global in scope, The Verso Book of Feminism shows the breadth of feminist protest and of feminist thinking, moving through the female poets of China’s Tang Dynasty to accounts of indigenous women in the Caribbean resisting Columbus’s expedition, British suffragists militating for the vote to the revolutionary pétroleuses of the 1848 Paris Commune, the first-century Trung sisters who fought for the independence of Nam Viet to women in 1980s Botswana fighting for equal protection under the law, from the erotica of the sixth century and the ninteenth century to radical queer politics in the twentieth and twenty-first.