Mao on the relationship between politics and art in the context of revolution

On the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, Christian Sorace explores Mao's argument for combining political and aesthetic criteria when judging a work of art.

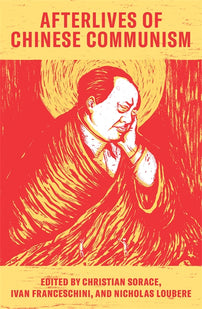

Afterlives of Chinese Communism, edited by Ivan Franceschini, Nicholas Loubere, and Christian Sorace, comprises essays from over fifty world-renowned scholars in the China field, from various disciplines and continents. It provides an indispensable guide for understanding how the Mao era continues to shape Chinese politics today.

Today, on the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, we present an excerpt from Afterlives of Chinese Communism, on aesthetics.

Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi is on sale now for 30% off.

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the north and south,

Turning a deep chasm into a thoroughfare;

Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west

To hold back Wushan’s clouds and rains

Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow gorges.

The mountain goddess if she is still there

Will marvel at a world so changed.

Excerpt from Mao’s poem ‘Swimming,’ June 1956

Mao’s poem ‘Swimming’ is a poetic evocation of the glorious changes that were intended to transform the Chinese nation through the collectivization of agriculture and accelerated industrial production. Written before the suppression of the Hundred Flowers Campaign (1957) and the launch of the Great Leap Forward (1958–62), the poem signals the way ahead with a sublime utopian vision. ‘Great plans are afoot’—natural chasms will be transformed into human thoroughfares. These scenes of industrious beauty obscure all traces of the destruction, rubble, displacement, and violence of transformation.

In Chinese, the word for ‘aesthetics’ (meixue ) is, literally, the ‘study of beauty.’ Still, as Haun Saussy points out, this term is misleading for many reasons. First, it was imported into China only in the nineteenth century by way of Japanese readings of German aesthetic philosophy. Further, in the vast skein of traditional Chinese thought, there was scant consideration of an aesthetic realm outside of the sovereign jurisdiction of the state. In this sense, Mao Zedong’s famous 1942 ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,’ in which he subordinates the aesthetic to the political, represents another faithful iteration of this tradition, with a Marxist gloss.

In this speech, Mao outlines the relationship between politics and art in the context of revolution, arguing that there are no absolute criteria for judging the value of art, only contextual and pragmatic ones. For Mao, art transforms reality in the process of reflecting it:

Although man’s social life is the only source of literature and art and is incomparably livelier and richer in content, the people are not satisfied with life alone and demand literature and art as well. Why? Because, while both are beautiful, life as reflected in works of literature and art can and ought to be on a higher plane, more intense, more concentrated, more typical, nearer the ideal, and therefore more universal than actual everyday life.

Although everyday life is ‘incomparably livelier’ than art, it is also more chaotic and complex. Art, so conceived, projects a better version of the everyday present, by which the masses can see a likeness of their future. The cultural sphere consists of models of behaviour, narratives, colours, sounds, and scenes which awaken revolutionary feelings. For Mao, the masses do not need art to remind them of their daily experience of ‘hunger, cold, and oppression.’ They need art to visualise the possibility of transcending their suffering.

On these grounds, Mao advocates combining political and aesthetic criteria when judging a work of art. Revolutionary content with lacklustre form does not stir the heart; conversely, an enchanting work of art can be a siren song of reactionary politics. For Mao, exemplary art fuses revolutionary content with high artistic quality. In addition to touching their souls, revolutionary works of art provide the people with representations of their own collective power and future. In this configuration, the fate of art and politics are inextricably bound together.

What falls out of the picture is what Fredric Jameson describes as the ‘implacable and sometimes even intolerable negativity’ of modern art, which is a necessary antidote to the pragmatism, empiricism, and common sense of daily life, not to mention the aesthetic rituals of state legitimation. This logic is absent from Mao’s Yan’an Talks. In 1942, revolutionary energies were too new and vulnerable to dissipation. They needed to be safeguarded by the correct ‘standpoint’ (lichang ) and ‘attitude’ (taidu ) of the artist:

From one’s standpoint there follow specific attitudes towards specific matters. For instance, is one to extol or expose? This is a question of attitude … . Many petty-bourgeois writers have never discovered the bright side. Their works only expose the dark and are known as the ‘literature of exposure.’ Some of their works simply specialise in preaching pessimism and world-weariness.

It is a slippery slope from aesthetic ‘exposure’ to nihilism to counterrevolution. To prevent this slippage, Mao limits art to a positive incarnation of political categories. Exposure is permissible, and encouraged, only when it is directed at enemies: ‘With regard to the [enemies] … the task of revolutionary writers and artists is to expose their duplicity and their cruelty and at the same time to point out the inevitability of their defeat.’ Toward allies, ‘our attitude should be one of both alliance and criticism,’ encouraging their achievements and chastising their apathy. ‘As for the masses … we should certainly praise them’ and patiently educate them to overcome their shortcomings.

After the victory of the revolution, art will continue to be a source of political intensity and inspiration for the masses, but similar to the victims of Pompeii, will also fossilize them in the representational forms of state power.

Antonioni’s China

In 1972, Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni was invited to China to film the sublime achievements of the Cultural Revolution. When it was released in 1974, Antonioni’s three-hour-and-forty-minute documentary film Chung Kuo triggered a virulent campaign of denunciation in China. Party leaders viewed the documentary as a ‘reactionary’ (fandong ), ‘anti-Chinese’ (fanhua ) attempt to humiliate China and denigrate the Chinese Revolution. People were encouraged to pen letters denouncing the film, even though it was banned from public circulation and only a handful of leaders had actually seen it. Discussion of this anti-Antonioni campaign has since been seldom raised. When it is mentioned, it is typically dismissed as a time-capsule of Maoera fanaticism. However, I suggest that the discursive rationality and affective energies of this campaign offer an interpretive key to official attitudes toward representations of China today.

CCP leaders at the time accused Antonioni of ‘making China ugly’ (chouhua ) by filming what they regarded to be the embarrassing blemishes of everyday life. For them, Antonioni’s film was anything but a beautiful contemplation of the ordinary—it was a form of national humiliation. In an editorial published in the People’s Daily on 30 January 1974, the authors argue that Antonioni’s purpose was ‘not to understand China’ but to ‘humiliate it. In response to Antonioni’s defence that he only intended to provide an ‘objective recording’ without judgement, the People’s Daily retorted that ‘each scene itself is a judgment.'

The main indictment against Antonioni’s documentary was not what it filmed, but what it did not film. Despite China’s revolutionary victory and massive transformations, in Antonioni’s film, China seemed to have changed very little, if at all. The lives of workers and peasants appeared to have barely improved since the prerevolutionary era; they toiled in similar conditions under different masters. According to the People’s Daily editorial, in Antonioni’s portrayal, ‘it seems as if China’s revolution has not changed the status of Chinese people and has not liberated them spiritually’—a direct challenge to the CCP’s legitimating narrative that it freed China from its feudal past. During the Mao era, campaigns were organised in which people would ‘speak bitterly’ (suku ) about the past, and ‘recall past bitterness in order to savour the sweetness of the present’ (yi ku si tian ) (see Javed’s essay in the present volume). People were enjoined to remember and be thankful for their new lives provided to them by the Party. Antonioni’s scenes of China’s past haunting its present challenged this logic of legitimation.

According to an editorial that appeared in the Guangming Daily on 13 February 1974: ‘In this way, in the movie, the Chinese Revolution is missing (bu jian ), the extraordinary changes brought about by the Revolution are missing, the radiant glory of new China is missing; instead, all that people can see is only the old China of last century.’ I have rendered bu jian in English as missing to make the translation smooth; however, in Chinese bu jian literally means to disappear from sight, implying that Antonioni’s camera intentionally did not record the positive aspects of China that were directly in front of his camera. The author accused Antonioni of shi’erbujian, which means to not see what is plainly there.

Framed in the unflattering light of Antonioni’s camera, rural China appeared full of people for whom the passage of revolutionary teleological time had stopped. In the words of the People’s Daily editorial, instead of filming revolutionary advances, Antonioni ‘spares no effort to find a withered farmland, lonely old man, weary beast of burden, and shabby building.’ What in reality is a ‘poor village,’ in the voice-over narration is labelled ‘a desolate and abandoned place.’ In the Guangming Daily editorial, the writer is baffled over Antonioni’s scene selections: ‘Instead of displaying industrial prosperity, [Antonioni’s camera] is transfixed on the backdrop of an elderly women sitting on the ground eating a popsicle.’ Why would he want to film a scene that is entirely foreign to Mao’s injunction that art must distil idealised forms of life?

From the CCP’s perspective, the only possible answer was that Antonioni’s aesthetic decisions were politically motivated technical manipulations to humiliate China. What could not be imagined was an aesthetic appreciation of the beauty of ordinary life. As Mao put it in his 1942 Yan’an Talks: ‘There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes, art that is detached from or independent of politics.’ It was impossible for the CCP to consider Antonioni as engaged in anything other than aesthetic sabotage. From the CCP’s perspective, Antonioni’s aesthetics were an ‘imperialist way of seeing’ (diguozhuyi de yanguang ). Ironically enough, after the ban on publicly screening Antonioni’s film in China was lifted in 2004, the movie has received praise by Chinese audiences, especially of that generation, for its depictions of a simpler and more beautiful life.

Reactionary Formalism

What is perhaps most interesting about these denunciations is their political critique of Antonioni’s formal techniques. ‘Anything good, new, or progressive, he did not film, filmed very little, or at the time pretended to film and then later edited out; any inferior, old, or backward scenes, he would film without turning the camera away.’ Even when Antonioni filmed what the CCP would have regarded as positive aspects of China, the editorial accused him of doing so from an unflattering angle. For instance, the footage he filmed of the bridge over the Yangtze River in Nanjing was said to have undermined this ‘magnificent’ and ‘modern’ structure. This was because the camera was ‘unsteady and swayed back and forth’ and even strayed to film someone’s ‘pants drying underneath the bridge.’ These intrusions of everyday life disrupted the monumental, revolutionary, and romantic longings of the Maoist aesthetic.

The CCP was enraged by more than just the ‘erratic’ style of camera-work. In their eyes, Antonioni meticulously edited scenes in a way that obliterated China’s revolutionary transformation. In the Imperial Palace’s Exhibition Hall, after filming sculptures of ‘oppressed workers rebelling’ during the Ming era (1368–1644) and describing their ‘miserable’ living conditions, the ‘camera shot cuts to a scene of young students sent down to the countryside to participate in labour’ insinuating that not much has changed between then and now. The voice-over narration concluded that there was no ‘paradise’ in the Chinese countryside. This statement probably struck a nerve, as it was quoted in several of the essays denouncing Antonioni. However, it is also worth considering the European context in which Antonioni’s film was made and received. Across Europe at the time groups of young self-styled Maoists fetishised the Cultural Revolution as an answer to their political desires (see Lanza’s essay in the present volume). As Jacques Ranci.re reflected: ‘There can be no doubt that we were bending the manifestations of the Maoist revolution a bit too quickly to our own desires for a communism radically different from the Stalinist one.’7 For the Chinese Communists, however, Antonioni’s statement could only be understood as a negation of revolution.

For the CCP, each aspect of Antonioni’s documentary was reactionary. The People’s Daily editorial complained about the ‘drab lighting and gloomy and cold tone.’ The film lacked the bright colours of revolutionary passion, and instead gave off a ‘gloomy, depressing, and unfeeling impression.’ On top of that, the musical score was also found to be offensive. Rather than highlighting China’s revolutionary model operas, Antonioni used Chinese music to ‘wantonly mock’ the revolution. In one a scene, a pig shakes its head in sync with lines from a revolutionary opera that said ‘lift up one’s head and stick out one’s chest’ (tai qi tou, ting koutang ). Scenes such as this one are marshalled as evidence of Antonioni’s malicious political intentions.

Antonioni’s camera recorded China in a way that challenged the official discursive and aesthetic frame of representation. The CCP’s response was to denounce the film as evidence of Antonioni’s imperialist gaze: you can’t see China because you only see what you want to see. He had failed the People’s Republic.

Ridiculing the Sublime

On 15 October 2014, in an unmistakable emulation of Mao’s 1942 Yan’an Talks, China’s leader Xi Jinping gave a ‘Speech at the Forum on Literature and Art.’8 Despite China’s rapid transformations over the last several decades, the CCP continues to vigilantly guard over—and censor—representations of China that challenge its idealised version of itself. Without the larger-than-life figures of revolution and communism as their horizon, Xi’s guidelines reduce art to the celebration of Party-sanctioned morality, cultural heritage, and nationalist sentiment.

In Xi’s version, the main purpose of art is to infuse reality with optimism for the future:

If literary and artistic creations merely write an account of the current situation, reveal an unmediated display of the repulsive side of things, and do not extol their bright side, if they do not express ideals and guide morality, then they cannot inspire the people to advance.

For Xi, art must marry ‘a spirit of realism’ and a ‘mood of romanticism,’ ‘use light to disperse darkness,’ ‘use the beautiful and good to defeat the repulsive,’ with the ultimate aim of ‘allowing people to glimpse the beauty, hope, and dreams that are in front of them.’

This definition of art prefigured Xi Jinping’s speech at the Party’s Nineteenth Congress, held in October 2017, during which he announced the arrival of a ‘New Era’ (xin shidai ) shaped by a new ‘principal contradiction’ (zhuyao maodun ) facing Chinese society. This contradiction results from the nation’s ‘unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life.’9 Xi used the term meihao when referring to a ‘better life,’ thus evoking the idea of an aesthetically pleasing and morally ordered life. For Xi, the duty of the artist is to produce visions of the good life, and the responsibility of the CCP is to create the socioeconomic conditions for its realisation. What his account cannot accommodate are representations that might diminish people’s optimism or call into question the CCP’s ability to engineer the future.

Xi’s speech continues the Party tradition of using political criteria to judge the value of works of art, and criticises alternative modes of valuing artistic creation. Like Mao, Xi argues against formal aesthetic criteria and the mentality of ‘art for art’s sake’ (see also Chan’s essay in the present volume). In his words, ‘the ultimate goal of all creative techniques and methods is to serve content … . To depart from this principle, technique and method are utterly lacking in value, to the extent of producing negative effects.’ Unlike Mao, however, Xi must also contend with the art market as a source of value for art as a cultural commodity. Unsurprisingly, Xi saves his harshest remarks for market driven sensationalist works of art that ‘ridicule the sublime’ and ‘exaggerate society’s dark side’ in the pursuit of profit. He described these works as ‘cultural garbage.’ Without formal aesthetic and market criteria to judge the value of a work of art, Xi submits that an artwork’s significance must derive from its ability to contribute to the ‘rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation’ (zhonghua minzu de weida fuxing ). Here, the negative —or critical function of art—is conflated with the anti-social, and often interpreted as being anti-Chinese.

Politics of Sight

The politics and contradictions surrounding Antonioni’s documentary film are still relevant today. Where is the truth in this melee of representations and mutual recriminations of misrecognition? Does one see the material successes of China’s economic miracle, its skyscrapers and high-speed rails, or its concentration camps in Xinjiang and environmental devastation? In an age of globalisation, the CCP asserts its ‘discursive rights’ (huayu quan ) to ‘tell China’s story well’ (jianghao zhongguo gushi ). It dismisses negative representations of China as the invidious attempts of China’s enemies to ‘damage the nation’s image’ and the ‘Party’s image.’ To be sure, there are negative representations of China that arguably harbour lingering colonialist desires and cold war animosities. However, what the Chinese Party-state is increasingly demanding is that the world defer to its control over how China is represented, thought about, and discussed as the price of doing business with it. What the CCP offers is a future in which the spark of Maoism, which has always been the power of the masses, is reduced to the cinders of history.