Marxism’s Living Soul?: A Reply to Paul Saba

The main reason to look back at the history of the New Communist Movement is to glean any lessons that can be useful for rebuilding a revolutionary left under today’s dramatically changed conditions.

First published in Viewpoint Magazine.

I appreciate Paul Saba’s serious treatment of Revolution in the Air. We share the view that the main reason to look back at the history of the New Communist Movement (NCM) is to glean any lessons that can be useful for rebuilding a revolutionary left under today’s dramatically changed conditions.

Saba and I agree on some of those lessons but disagree on others. Our differences are related to differing interpretations of the history of the NCM; more specifically, different views of the what role the polemics between the Chinese and Soviet Communist Parties and the Sino-Soviet split played in the movement’s evolution (and U.S. and global politics in general). Those differences have theoretical and political implications that remain relevant even though the historical era in which the Sino-Soviet dispute shaped much of the left is behind us. In this response to Saba’s in-depth review I would like to sharpen the debate between us over NCM history and, on that basis, argue that Saba’s insistence on using the Chinese Party’s “anti-revisionism” framework points the left toward overly-rigid notions of Marxist theory, and, in turn, a view of the relationship between theory and politics that favors schematic formulas over concrete analysis of concrete conditions.

Third World Marxism

Saba begins his critique of what he considers the theoretical and historical weaknesses of Revolution in the Air. His opening contention is that “Third World Marxism” — a framework I use to bind together the varying ideological coordinates of the New Communist Movement — is an unhelpful concept for understanding the New Communist Movement. The centerpiece of his argument is that Third World Marxism was not “a distinct independent form of Marxism.”

That last point is accurate. In fact, Saba admits that my book discloses as much itself. But that does not make it inappropriate — much less misleading or wrong — as a framework for understanding a movement that was as fragmented, diverse, youthful and theoretically underdeveloped as the NCM. Saba does not challenge (or even discuss) the theoretical as well as the political and organizational views Revolution in the Air identifies as characterizing the Third World Marxist current and the party building component within it:

In tune with the central axes of 1960s protests, Third World Marxism put opposition to racism and military interventionism front and center. It riveted attention on the intersection of economic exploitation and racial oppression, pointing young activists toward the most disadvantaged sectors of the working class. It embraced the revolutionary nationalist impulses in communities of color, where Marxism, socialism and nationalism intermingled and overlapped. It linked aspiring US revolutionaries to the parties and leaders who were proving that “the power of the people is greater than the man’s technology”: the Vietnamese and Chinese Communist Parties; Amilcar Cabral and the Marxist-led liberation movements in Africa; Che, Fidel and the Cuban Revolution.

In spirit as well as focus all this fit the 1968 generation’s mood much better than did the variants of Marxism offered by the 1930s-descended “Old Left.” These had been shaped by the Soviet experience and were oriented mainly toward the trade union movement.

Third World Marxism promised a break with Eurocentric models of social change, and also with the political caution that characterized Old Left groups, communist and social democratic alike. It pointed a way toward building a multiracial movement out of a badly segregated US left…

Within the Third World Marxist ranks, a determined contingent set out to build tight-knit cadre organizations. These activists recognized that a slacking off in mass protests could be on the short-term horizon. But they believed any such lull would be short-lived and followed by upsurges even more powerful than 1968’s. And they believed that it was urgent to prepare a united and militant vanguard so the revolutionary potential glimpsed in the 1960s could be realized next time around. 1

This approach to understanding the New Communist Movement captures its particular historical moment and what separated it from the rest of the left, yet allows room for the incredible diversity within it.

Saba suggests it would be better to restrict analyzing the NCM through the ideological frames of Maoism and anti-revisionism. But his own writing contains examples of how limiting this would be in capturing the breadth of the movement and the obstacles that this would pose for identifying its underlying impulses.

Saba writes that it would have been better if my book had been able to give more attention to some of the “less well-known, out of the way groups.” I agree. But more attention to the militantly anti-Stalinist Sojourner Truth Organization, or to the numerous collectives that were led by activists whose main ideological formation came via Cuba and the Venceremos Brigades, would only have reinforced the reasons to utilize the ideologically broader “Third World Marxism” framework. Likewise it is a “Third World Marxist” frame that better explains how an NCM group that Saba cites favorably in a previous article in Viewpoint would choose the name Amilcar Cabral/Paul Robeson Collective when neither Cabral nor Robeson were in any way “anti-revisionist”; and why the Guardian newspaper — more influential in the party-building movement’s early years than any other NCM formation — insisted that Cuba’s intervention in Africa was a shining example of proletarian internationalism when Maoist China and its US supporters were bashing Cuba as a “puppet of Soviet social-imperialism.” The interesting discussion of League of Revolutionary Struggle in Saba’s review also is evidence that, whatever the ideological pronouncements of a self-defined pro-China anti-revisionist organization, an underlying commitment to the liberation of peoples of color was a more powerful force in determining a group’s actual strategy and practice.

The CPC-CPSU Polemics and “Anti-Revisionism”

If a broader frame than Maoist “anti-revisionism” is needed to capture both the breadth and the actual political dynamics of the NCM’s development, does that require downplaying the impact of Maoism? Not at all. And Revolution in the Air does not do so. But it offers a different assessment of the role Maoism in general and the theoretical framework of “anti-revisionism” in particular played in the NCM and the global left.

Saba’s review argues that the Chinese Communist Party under Mao played an overwhelmingly positive role with its launching of polemics against the CPSU in the early 1960s. He concedes that the CPC’s viewpoint ultimately led to a “theoretical dead-end” and agrees that China over time backed “reactionary regimes and movements” as long as they were anti-Soviet and moved toward a “de facto alliance with the U.S.” But he claims the initial polemics had “an enormous positive impact… helped inaugurate a new period, creating a breach in the monolith…and demanded a debate on a whole series of fundamental problems” including “the problem of modern revisionism.” He criticizes Revolution in the Air for not being hard enough on the CPSU and simply reducing the split to “little more than a tragedy” despite my writing that “the Sino-Soviet split was a disaster for the entire global alignment against Western imperialism." 2

I think this is a misreading of both history and my book.

This “new period” was a time when crisis of the Soviet-led communist movement was exposed, and debate came to the surface both within and outside of Communist Parties. It began in 1956, several years before the Chinese polemics. That watershed year included the CPSU’s 20th Congress, Khrushchev’s secret speech, and the Soviet military intervention in Hungary, as well as politically diverse responses by communists around the globe. In some countries like the United States, this auditing of the communist past and the future course of the left were public, even reaching proportions that threw the party into crisis. Elsewhere it was more muted, while leading still to breakaways and new initiatives. Britain would count among the latter camp, where the new crisis would provide ground for the formation of new movements, journals, organizations and clubs, whose vibrant ecosystem was so brilliantly described in Stuart Hall’s “Life and Times of the First New Left.” Whatever pre-1956 consensus (“artificial” or otherwise) existed among parties as vastly different as the Italian, Vietnamese, Iraqi, Cuban, Japanese or Korean, after the death of Stalin, these parties began to make strategic decisions for themselves, regardless of the orders from Moscow.

This crisis in Marxism was coeval with the explosive revolutionary activity in the global south; the 1955 Bandung Conference, the rise of the Non-Aligned Movement, the Cuban Revolution, and the acceleration of anti-colonial liberation struggles in the Third World suggested for many young radicals that revolutionary elan was no longer the exclusive province of the Soviets. New organizations for revolutionary struggle were not just a theoretical option but, increasingly, a political reality.

The Chinese polemics described by Saba were part of this broader process. But their main impact was not merely to “demand a debate” on the orientation of the international communist movement. Rather, it was to argue that a particular assessment of communist history, theoretical framework, political strategy, and organizational approach provided the solution to this crisis, which they interpreted as an alleged betrayal of Marxist-Leninist principles by the CPSU. The CPC asserted that the policies and outlook of the CPSU had been revolutionary under Stalin, and framed the wide-ranging debate as a manichean conflict between Stalin’s genuine Marxism-Leninism and “revisionism.”; The CPC’s political strategy was merely reheated older Comintern positions, insisting that the advent of nuclear weapons didn’t change much — if anything — about how class and political struggle would unfold; the organizational perspective that flowed from this was to reaffirm a proposition entrenched in the Stalin period: that there could be one and only one genuine revolutionary party in each country, and so the task was to form such parties in all countries on an anti-revisionist basis. Bottom line, the polemics simply argued that one form of communist orthodoxy should be replaced by another.

Saba is right that the polemics which laid out these propositions in the early 1960s were “carefully reasoned.” But what is missing from his review is the penetrating critique of what that reasoning came up with that he himself offered in another Viewpoint article:

the Maoist leadership chose to present their critique of the Soviet line as one of defending orthodoxy in communist politics and theory against revisionism. This was a fatal mistake. As the French communist G. Madjarian correctly noted: “The fight against ’revisionism’ cannot be waged by conserving, or rather, by merely re-appropriating, Marxism as it existed historically in the previous period. Far from being the signal for a return to the supposed orthodoxy of the preceding epoch, the appearance of a ’revisionism’ is a symptom of the need for Marxism to criticize itself.

Indeed, the entire history of Marxism was frequently recast in Chinese polemics as a “two-line” struggle between orthodoxy and its opponents. Since the Soviet line being criticized was said to have emerged after Stalin’s death, Maoism divided the history of the Soviet Union and the world communist movement into two distinct periods. First, the correct and revolutionary era that began with Lenin and came to an end with Stalin’s death and the triumph of Khrushchev, followed by a second period of revisionism and betrayal.

Many young activists during the 1960s, in the U.S. and elsewhere, were indeed inspired by the militancy of the Chinese polemics and by the grassroots mobilization exhibited at the onset of the Cultural Revolution. Maoism in the forms that it was popularized within the U.S. by magazines like Monthly Review, books like William Hinton’s Fanshen, and the Black Panther Party’s distribution of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse Tung (the “Little Red Book”), were among the influences that raised our revolutionary hopes, but so were the Cuban Revolution, the Vietnamese resistance to U.S. imperialism, and the overall surge of national liberation movements across Asia, Africa the Middle East and Latin America.

It would incorrect to tell a declensionist story of anti-revisionist politics; it was not the case that their polemics were initially theoretically sound and on target, before later-day interpreters took them off-track. To be sure, the views and practices of the CPSU deserved forthright criticism (for instance, its conflation of Soviet state interests with the interests of the international working class, its shallow and self-serving evaluation of the Stalin era, its attempts to dictate policy to other parts, and much more). But the Chinese view was flawed from the outset, hobbled by its defense of orthodox formulas from the Stalin period under the rubric of “anti-revisionism.” The full negative consequences of this flaw took several years to make themselves felt, especially when the CPC declared that the USSR had restored capitalism and become the more dangerous of the “two superpowers.” But the problem was there from the beginning.

Was the NCM founded on false premises?

The answer to that question is yes only if one thinks that unless the CPSU and CPUSA were “revisionist” it was illegitimate to form a different revolutionary organization. I don’t agree with that criterion, so my answer is no. The NCM was based on a set of political and theoretical ideas different from the CPUSA, Social Democracy, Trotskyism and anarchism, and its perspective was a field of force attracting thousands of dedicated 1960s radicals. There were serious flaws in what united all strands of the NCM, and it was foolish for us to think no other tendency on the left was “genuinely” socialist or Marxist. But it made complete sense to take the many strengths of the Third World Marxist current and try to turn them into a politically and organizationally coherent force.

On a more general level (and a point well worth stressing today) freeing ourselves from the anti-revisionist straitjacket of “one exclusive vanguard/only one genuine Marxist tradition” makes it far more possible to build organizations that are appropriate for changed conditions and able to explore new theoretical ground. It allows for healthier modes of debate and cooperation with others on the left — and within one’s own movement — than the NCM practiced. Strivings for a “franchise” from one or another prestigious party, or for a theoretical holy grail that gives one the keys to the kingdom of truth, can be dispensed with in favor of a focus on politics and strategy under the “conditions directly encountered.” Groups can struggle over differences with a sense of proportion; no longer are the stakes determining which one (and only one) is truly revolutionary. Likewise, the potential for left forces who have different ideological histories converging via a process of practical cooperation and comradely debate becomes a desirable scenario rather than a heresy. Precisely that happened in El Salvador, where five different revolutionary groups converged to form the FMLN including the “traditional’ Communist Party, which dramatically shifted its views concerning strategy and the role of armed struggle in the process.

The specifically Maoist framework bears only some of the responsibility for the NCM’s failure to evolve in that healthier direction. As Revolution in the Air argues, despite considerable dynamism in its early years, every one of the larger components of the NCM (including the organization I was among the leaders of) either embraced the “return to orthodoxy” model from the beginning or fell back into it as they attempted to explain why the promise of the early 1970s was not being realized. Some of the smaller groups (including Theoretical Review, of which Saba was editor) were less afflicted with this problem. But they were unable to develop the political traction required to set the movement in a different direction.

Our respective differences in analyzing the Sino-Soviet split are related to this issue of “premises.” If one believes that anti-revisionism is the only legitimate basis for building a revolutionary party that doesn’t follow the line of the CPSU, then it makes sense to stress the positive side of the Chinese stance. Even if China eventually fell into a de facto alliance with U.S. imperialism (as Saba concedes it did), credit is given to the split for getting anything other than a Soviet-tailing global left off the ground in the 1960s.

The problem with this view is that across the globe many Communist Parties went their own way without accepting China’s “anti-revisionist” framework. New revolutionary formations did the same throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The Vietnamese rebuffed both Soviet and Chinese “advice” and determined their own (winning) strategy. Cuba criticized both the USSR and China for not “following genuine Marxism-Leninism.” The PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau led by Amilcar Cabral, the MPLA in Angola, FRELIMO in Mozambique and numerous new forces throughout Latin America pursued armed struggle strategies without utilizing the framework of anti-revisionism. The Marxist groups that spearheaded the Palestinian left, especially the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, openly disagreed with both the Soviet and Chinese lines (and reserved their harshest criticism for the latter). In Italy new Marxist formations to the left of the PCI (and much more influential in their country than the NCM was in the U.S.) were sympathetic to China without embracing “anti-revisionism.” These and other organizations,especially in the Third World, were on the frontlines of the global struggle against imperialism in the 1960s and ‘70s. For these groups, the split between the two largest socialist powers — which was translated for on-the-ground politics as a practical policy of “no united action with revisionism” for Chinese-aligned militants — badly weakened their struggles. I see no reason, therefore, to retreat from this assessment made in Revolution in the Air: “The Sino-Soviet split was a disaster for the entire global alignment against Western imperialism and the result of realpolitik maneuvering, nationalism, and factional interests on both sides." 3

Defending Marxism: Focus on its Tradition or its Living Soul?

Last, Saba suggests that he and I have a “basic ideological disagreement” because we have different ways of formulating our views of Marxism and how best to revitalize the quality of Marxist analysis and Marxism’s overall influence. I don’t think our difference here is “basic.” But we do approach this issue in different ways.

The point of departure for Saba’s critique here is a passage in Revolution in the Air that criticizes the NCM for "belief in a single and true Marxist doctrine with an unbroken revolutionary pedigree from 1848 to the present." 4 He goes on to suggest that this passage combined with the book’s critique of the “anti-revisionism” framework, abandons any serious defense of Marxism. His recommendation regarding what is most needed today is this: “Given the ideological eclecticism of much of the growing new American left, now more than ever it is necessary to stress the critical importance of this [Marxist] tradition and the political necessity of defending it from the numerous ideological currents hostile to it.”

I’m all for defense of Marxism and a revolutionary outlook: the last section of Revolution in the Air is sub-headed "Re-legitimizing Revolutionary Politics." 5 But I see the best road to accomplish that in a different way. For reasons already stated I think pinning the argument for Marxism on defense of “anti-revisionism” will lead to a dead end. And it seems to me that arguing we will make headway by putting priority on defending Marxism from “hostile currents” is simply a different way of phrasing this same backward-looking approach.

The road to expanding Marxism’s influence is by understanding its past weaknesses in order to renew and enrich it. Part of this is winning the battle of ideas — offering analyses of both current events and underlying trends that illuminate what is taking place more sharply and accurately than assessments coming from other quarters. But even more than that, Marxism’s influence will grow when organizations and movements informed by Marxism gain large-scale influence in the working class and communities of color and begin to affect the direction of the country.

Today’s left is indeed ideologically eclectic. That has been true of virtually every new surge of radicalism, in any country, over the last hundred years. That reality will not change mainly by arguing that there is a valuable Marxist tradition to be defended, but by drawing on that tradition — as well as on the most advanced ideas in bourgeois thought, as Marx did in his time — and producing analyses and strategies that reach people intellectually and move them politically. Moreover, it is vital to establish a different relationship between Marxists and partisans of other radical and revolutionary frameworks than the NCM or any orthodox Communist Party of the pre-1989 period advocated. Theoretical debate of course; but for rebuilding a relevant U.S. left the more pressing challenge is to struggle for as much common ground as possible on the level of political program and strategy.

And this is where there is one more crucial point to be made in looking at the history of the NCM. What is most striking about Saba’s review of Revolution in the Air is that it never engages with what that book argues was the most basic and costly error of the whole project, namely the failure for NCM organizations to historically situate their political analysis and adapt their strategies to unforeseen developments.

Revolution in the Air argues the point this way:

The essential failure of the new communist movement…is that the movement was unable to accurately assess the conditions it faced – either initially or after a few years of inevitable mistakes and misjudgments – and instead pursued strategies and tactics that squandered rather than developed its initial energy, dedication and potential…the cadre who built the new communist movement adopted a one-sided and over-optimistic sense of the possibilities at hand. They were hardly the first to make this mistake: Marx, Lenin, and the communists of the 1930s all thought in their turn that capitalism was on the verge of decisive defeats. But though the revolutionaries of 1968 followed in honorable footsteps, their misjudgment was nonetheless costly. It led to unrealistic projections about the balance of class forces, a serious misassessment of the main direction of 1970s politics, ultra-left tactics in mass movements and sectarian policies toward progressive reformers and other tendencies on the left. It fostered hyper-inflated rhetoric, organizational structures and an overall style of work that was out of touch with the sentiments of the social base the revolutionaries were trying to reach.

Further, misassessment of the historical moment pushed the new communist movement toward ideological frameworks that reinforced rather than tempered their voluntarist bent. The grip of those frameworks, in turn, made it harder rather than easier to readjust as the 1970s unfolded differently than these young revolutionaries had anticipated. 6

Utilizing a rigorous Marxist framework to analyze the world is an excellent place to start. But there is no framework, no formula, no method, that directly yields — much less guarantees — an accurate assessment of objective conditions, the balance of class and social forces or what the next phase of battle will look like. Without that kind of assessment, one cannot succeed in politics, that is, in changing the world. That’s why Lenin wrote that “concrete analysis of concrete conditions” was the “living soul” of Marxism.

Today’s resurgent left can ill-afford to repeat the mistakes of the NCM in this regard. We are all encouraged by the surge of radical activism in this country since Occupy, #BlackLivesMatter, Bernie Sanders’ campaign, and the election of Donald Trump. The explosion of expressed support for socialism by young people is a source of great hope. But what is the actual level of influence of the left in a situation where, as Saba accurately notes, “the international balance of forces still favors the right”?

How deep are the reserves, the roots, and the international ties of the white nationalist-driven authoritarian current that has captured one of the two major parties and now controls all three branches of the federal government and more than half the states? What is the relative strength of the different wings of a “resistance” that stretches from corporate Democrats through a dynamic grassroots upsurge rooted in communities of color and among young people? What differences within the ruling class are deepest and can be best taken advantage of by progressive and revolutionary actors? What are the main ideological currents within the social sectors that could constitute the base of a durable socialist politics? Do we think democratic and working class movements in the US and globally will be facing a relatively lengthy period of defensive struggles and rebuilding, or do we foresee a turn to the offensive just around the corner?

In my view, it is answers to questions on this level, and the strategies derived from them, that will determine how much progress those trying to revitalize the U.S. left today will make. In this exchange Saba and I have offered our views on what the left current we were part of did right, what we got wrong, and what might be learned from the overall NCM experience. Take anything you find useful from our conclusions and our debate and leave the rest.

Notes

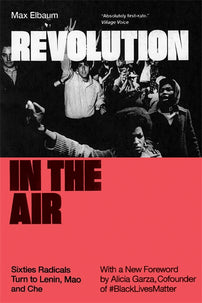

1. Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che (London: Verso, 2018), 3.

2. Ibid., 89.

3. Ibid., 89.

4. Ibid., 324.

5. Ibid., 336.

6. Ibid., 320-321.

Max Elbaum was a member of Students for a Democratic Society and a leader of Line of March, one of the main new communist movement organizations. His writings have appeared in the Nation, the US Guardian, CrossRoads, and the Encyclopedia of the American Left, and his book, Revolution in the Air was published by Verso Books. He lives in Oakland.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]