Debord and Marquez at Fifty

This year sees the Golden Jubilee of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Both are darkly pessimistic texts that speak to our times. They pinpoint the shortcomings of the 1960s generation as much as embody its utopian desires. They transmit a strange optimism, a backdoor sense of hope, and offer another take on what our lives might be.

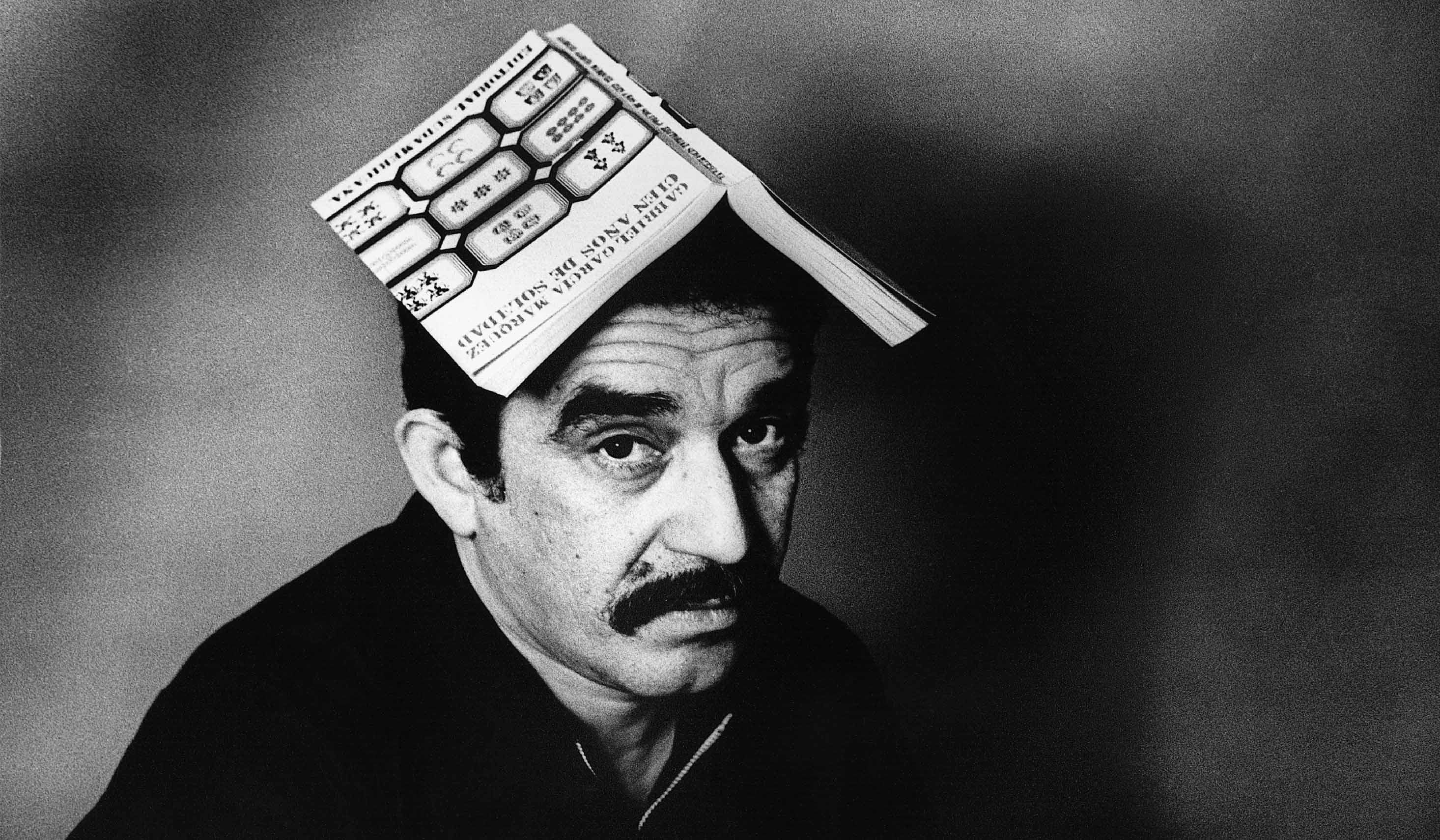

In this essay Andy Merrifield, author of The Amateur, looks at the importance of these texts on their 50th Anniversary.

This year sees the Golden Jubilee of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. With spellbinding brilliance both books continue to fascinate readers. Few think of Debord, the prophet of spectacular capitalism, as a magical realist, just as fewer still would see Garcia Marquez, the prophet of magical realism, as a theorist of the spectacle. Yet it’s possible to conceive both men in this guise and posit their respective masterpieces as works of art that push reality beyond realism.

The Society of the Spectacle and One Hundred Years of Solitude open up different doors of perception, so maybe it’s no coincidence that they appeared the same year Jimi Hendrix wondered Are You Experienced? and The Doors demanded “the world and we want it now!”; when the psychedelic “Summer of Love” raved and the Pentagon levitated in a giant carnival protesting the Vietnam War.

Both are darkly pessimistic texts that speak to our times. In a way, they pinpoint the shortcomings of the 1960s generation as much as embody its utopian desires. They transmit a strange optimism, a backdoor sense of hope, and offer another take on what our lives might be. Each book shows us how reality can be represented differently, how more acute and astute forms of subjectivity can create a more advanced sense of realism, and a different type of objectivity.

*

Legend has it that Garcia Marquez was driving to Acapulco for a family vacation when his Latin American Don Quixote came to him in a flash. Turning his car around, he returned to Mexico City, and for the next eighteen months tapped away on his Olivetti electric typewriter a story that had been in his head for eighteen years. “All I wanted to do,” he said, “was to leave a literary picture of the world of my childhood which was spent in a large, very sad house with a sister who ate earth, a grandmother who prophesized the future, and countless relatives of the same name who never made much distinction between happiness and insanity.”

On sale fifty years ago this month, in Buenos Aires, a few weeks before Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released, One Hundred Years of Solitude opened with Marquez’s re-imagined childhood memory:

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

But the bizarre saga of the Buendias in the town of Macondo, hacked out of the middle of damp Colombian jungle, not far from a barnacle-encrusted Spanish galleon, takes on a reality way beyond a quaint family romance. It’s a paradise found and lost, a saga of a magnificent and miserable humanity, a mad dream of damaged characters whose only goal in life is to live out a wonderful human adventure.

For Marquez writing could, and should, be a poetic transformation of reality. The source of creation is always reality, yet a reality in which imagination is an instrument in its production and re-creation. “Things have a life of their own,” Melquiades, the gypsy magician reminded José Arcadio Buendia. “It’s simply a matter of waking up their souls.”

*

Hitting Parisian bookstores in November 1967, The Society of the Spectacle would get daubed on walls across France six months later, waking up the souls of a generation caught between Marx and Coca-Cola:

“DOWN WITH THE SPECTACULAR COMMODITY ECONOMY,” “TAKE YOUR DESIRES FOR REALITY.”

With its 221 short, intriguing theses, aphoristic in style and peppered with irony, The Society of the Spectacle remains our greatest political prose poem. Throughout are compelling evocations of a topsy-turvy world. Everything and everybody partakes in a perverse paradox; “the true,” says Debord, “is a moment of the false.”

Inventive Marxist tools describe and analyze a new phase of capitalist reality, one that seems to have decoupled itself from its material thing-base, and rematerialized as an image, as a spectacle. “Everything that was once directly lived,” Debord says, “has moved away into a representation.”

Debord’s insights in The Society of the Spectacle are brutally realistic descriptions and inversions of what is, and projections of what might be. Sometimes he conjures up the realm of dream, releasing unconscious yearnings, sublimating deep political desires. And yet to dream one needs to sleep.

*

Nobody sleeps in Macondo when it succumbs to an insomnia plague. At first, no one was concerned about not sleeping because there’s always so much work to do and so little time to do it. But after a while a fearsome illness takes hold. Soon “the recollection of their childhood began to be erased from their memory, then the name and notion of things, and finally the identity of people and even the awareness of their own being, until the person sank into a kind of idiocy that had no past.” The expert insomniac eventually forgets about dreams, and about dreaming. And even though nobody sleeps a minute, the following day people feel so rested that they forget about the bad night they’d had.

What’s fascinating about Marquez’s notion of the insomnia plague is how it captures the equally bizarre reality of Debord’s “society of the spectacle,” where “the sun never sets on the Empire of modern passivity.” Debord says this society is founded on “the production of isolation,” a condition that reinforces the idea of a “lonely crowd,” of people bound by a common economic and political system yet forged together in a “unity of separation.” The spectacle is the “nightmare of imprisoned modern society which ultimately expresses nothing more than its desire to sleep.” But it can’t sleep, because the spectacle “is the guardian of sleep.”

Marquez’s portrayal of the insomnia plague pinpoints how the reality of real truth and the reality of illusion are one and the same. There’s no real way to tell either apart. The reality of an insomniac turned amnesiac. Fact and fiction mutually conspire to negate each other. The blurring of opposites speaks bundles about Debord’s society of the spectacle, about how it possesses us body and mind, and how it now begets a different political agenda.

*

Yet not everyone is smitten by the spectacle. We’ve always had people hell bent on staving off the insomnia plague. People like Colonel Aureliano Buendias, inspired by strange gypsies who’ve tried to uphold the power of dreams, dreams of a future for Macondos arising out of wild swampland. In this sense, Colonel Aureliano Buendia, the introverted soul spurred into militant direct action, might be something of a twenty-first-century radical role model, inspiring us to fight against our slipping away of reality.

The Colonel creates another reality out of his own subversive will. He doesn’t reveal or discover anything through theory. Instead, he creates, pioneers a new trail for a reinvigorated, less defensive kind of political practice. Even as the insomnia plague raged, young Aureliano conceives a formula to resist, to help protect against memory loss. He invents a system of marking things with their respective names, using little pieces of paper pasted on every object. This feels like preparation for later revolutionary actions.

And so they are. One Sunday morning, drinking his habitual mug of black coffee, Aureliano tells his friend Gerineldo Marquez in a voice the latter had never heard before, “Get the boys ready. We’re going to war.”

“With what weapons?” Gerineldo wonders.

“With theirs,” Aureliano rejoins.

From that moment on, dressed in black high boots with spurs, an ordinary denim uniform without insignia, Colonel Aureliano Buendia, the commander-in-chief of the revolutionary forces, the anarchist warrior and man most feared by the government, is born. He’d reinvented his own radical self through engaging with the world. “On his waist he wore a holster with the flap open and his hand, which was always on the butt of the pistol, revealed the same watchful and resolute tension as his look.” When Ursula, Aureliano’s mother, Macondo’s great matriarch, sees him then, she says: “Good Lord, now he looks like a man capable of anything…I always thought and now I have proof that he’s a renegade.”

*

One is struck by the strange affinity between Colonel Aureliano and the Situationist Guy Debord, the thirty-six-year-old author of The Society of the Spectacle. After all, both have a penchant for militant action and muckraking; are elusive and charismatic presences; have melancholic dispositions, demonstrating occasional ruthlessness toward friend and foe alike.

And both fervently believe that politics is another form of war, an art-form of resistance, a game of strategy, one that should be studied as well as practiced. Furthermore, their penchant for battle arises out of a marked distrust of professional career politicians. “We’re wasting time,” the Colonel says, “while the bastards in the party are begging for seats in congress.” Debord similarly believes that active engagement is the only viable alternative to representative democracy, to the alienation of the spectator.

Their resistance is non-negotiable, moodily romantic and innately poetic. Perhaps the line in One Hundred Years of Solitude that so magnificently captures the spirit of each man’s radicalism is when Marquez describes the Colonel as “sneaking about through narrow trails of permanent subversion.” It’s a memorable phrase we should now chalk up on a wall somewhere.

Debord says reality emerges by converting negative practice into an affirmative living ideal. It means, maybe more than anything else, opposing “spectacular time” with “lived time,” recreating a real, imaginative life where one is true to oneself in a world of true others. The old Catalan bookseller near the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude is instructive because his customary good cheer was sustained, Marquez says, by “his marvelous sense of unreality.” Yet once this wise old man started to get too serious, too analytical and nostalgic for a paradise lost, his marvelous state began to crumble, began to turn cynical and bitter, poisoning his joy of life.

*

And what will we find within the life lived in this way? Remedios the Beauty, Macondo’s most dazzlingly attractive daughter, arguably embodies the qualities of what this marvellous society might entail. Marquez says that Remedios the Beauty “symbolizes subversion,” that her startling “simplifying instinct” frustrates authority. She wanders about the Buendia’s house stark naked, in total liberty, and with her exceptional purity was able “to see the reality of things beyond any formalism.” Even the Colonel “kept on believing and repeating that Remedios the Beauty was in reality the most lucid being that he had ever known.” She exists in a world of simple unmediated realities and is immune from the insomnia plague when it struck. Therein, perhaps, resides the real solution for reclaiming the lived from represented.

This was also what Macondo’s two last remaining Buendias—Amaranta Ursula and Aureliano, the Colonel’s great-grandson—created in the stunningly moving finale of One Hundred Years of Solitude. “Don’t let it get away,” they’re reminded. “Life is shorter than you think.” They don’t let it slip away. A hurricane sweeps through them, and, as a couple, they discover the sensuality of Being, and the power of the right to love.

Maybe, then, in the rubble of our crisis-ridden culture, the 50th anniversary of Debord and Marquez’s masterworks isn’t so much a wake-up call to get “real” as a invitation to dream big, to open our canvas out onto an epic, romantic stage, to fight for the right to love.

For what we have here are two tragic love stories. Both books ask us to imagine that love can negate the politics of hate, that it can be the nemesis of the ugliness of global power. One Hundred Years of Solitude and The Society of the Spectacle are hopes against hope that it’s not too late to create a utopia of peace, that good will might prevail come what may, and that people do have a second opportunity on earth. If nothing else, they force us now to rethink what realism really means.

Andy Merrifield is the author of The Amateur, a passionate manifesto for the liberated life, one that questions authority and reclaims the iconoclast as a radical hero of our times.