Reconceptualizing Family History

"Frustrated by the fact that most texts on women treated 'the man's world' as the given and then simply asked where and how women fitted in," Stephanie Coontz writes, "I decided to undertake a survey of American gender roles: that was the starting point of the present book" — The Social Origins of Private Life: A History of American Families 1600–1900, published by Verso in 1988.

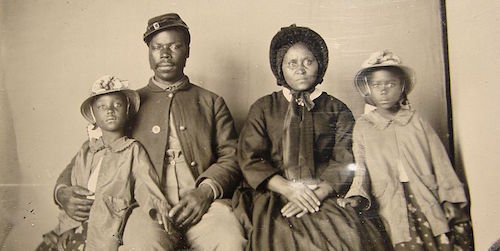

Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters, c. 1863-65. via Wikimedia Commons.

As the focus of her research shifted from "woman's private sphere" to the family as a larger arena in which the public and private intersect, Coontz became more attentive to the diversity of household arrangements across time and space. "Stimulated by the burgeoning research into family history," she writes, "I began to look at the family as a culture's way of coordinating personal reproduction with social reproduction — as the socially sanctioned place where male and female reproductive activities condition and are conditioned by the other activities into which human beings enter as they perpetuate a particular kind of society, or try to construct a new one."

From this conception, the book traces the evolution of American family structures through the nineteenth century, from pre-colonial Native American kinship and gender systems to the consolidation of working class and middle class family forms in the 1870s-90s.

Below, in two parts, is the book's first chapter, in which Coontz surveys Western debates about family history over three centuries and situates her distinct approach in the literature.

This book is a historical and analytical account of the evolution of American families from the seventeenth century to the 1890s. Before attempting to synthesize the ways in which “the family” has changed, however, it is worth noting the difficulty of identifying a single family unit that permits cross-cultural and historical comparison. In seventeenth and eighteenth century England and America, family was generally defined as all those living under the authority of a household head. “I lived in Axe Yard, having my wife, and servant Jane, and no more in family than us three,” wrote Samuel Pepys in his diary. Such was still the definition of Everard Peck, of Rochester, New York, in 1820, who wrote home shortly after his marriage: “We collected our family together which consists of seven persons and we think ourselves pleasantly situated.” Yet by this period many members of the middle class had begun to emphasize the exclusiveness of the parent-child unit, rejecting colonial traditions wherein household heads had made little distinction between children and servants of about the same age. At the same time, European aristocrats continued to define family in terms of those having claim to land and title, regardless of distance in time, geography, or genetic relatedness.1

Native Americans had still different conceptions of family: some groups stressed lineal descent, either through the paternal or maternal line; others paid more attention to horizontal ties of kinship than to vertical ones. In all cases, however, Native American family definitions extended well beyond the household and occasionally cut across it, with spouses identified as members of different families. Nineteenth-century white women also defined family as extending beyond the household, but they usually referred to predominantly female networks whose concerns were explicitly opposed to the work and political relations organized by Indian kin ties.

Even the biological facts about families are sometimes ambiguous. In many African and traditional Native American societies, a woman could become a female husband and be counted the parent of the children her wife brought to the marriage or afterwards bore by various anonymous lovers. A woman among the Nayar of India could take a tali husband whom she might see only at the wedding ceremony; he nevertheless legitimated her future children. Fictive kinship ties were important among Native Americans and Afro-American slaves, while “going for sisters” or brothers has been an important element of survival among poverty-stricken ghetto residents.2

Cross-culturally, families vary so greatly in their gender, marital, and child-rearing arrangements that it is not possible to argue that they are based on universal psychological or biological relations. We are accustomed to thinking of the mother-child relationship as critical to the family, but among the Lakher of Southeast Asia a mother is linked to her child only by virtue of her relationship to the father. If the parents divorce, the mother is considered to have no relationship to her children: she could, theoretically, even marry her son, since the group's incest taboos would no longer be considered applicable. (The widespread practice of brother-sister marriage among ancient Egyptians even throws into doubt the universality of such incest taboos.) Nor is the nuclear family the central reference point for many societies. Among exogamous unilineal kin groups such as the Basoga of East Africa, “nuclear families tend to be split by the conflicting loyalties of the spouses,” so that children orient to parental lineages rather than to the nuclear family in which they are reared. Among nineteenth-century Cheyenne Indians, the most significant economic and emotional exchanges occurred between children and their uncles or aunts rather than their fathers or mothers.3

Following G. P. Murdock, many authors have defined the family as a social unit that shares common residence, economic cooperation, and reproduction. But in groups as diverse as eighteenth-century Austrian peasants and the modern Yoruba, the legally or socially sanctioned family often did not share the same residence, engage in child-rearing, or cooperate economically in either production or consumption. In some tribal societies husbands and wives live apart, while in other societies the basic unit of economic cooperation may be the band, the age group, or the gender group rather than the family. And the history of sexuality surely demonstrates that reproduction often takes place outside the family, a fact which sometimes achieves legal recognition in institutions of concubinage, adoption, and so on.4

Sociologists and psychologists have emphasized the family's role as an agent of socialization: Mark Poster suggests that the family is a “system of love objects” in which psychic structure is decisively formed; more modestly, Ira Reiss claims that the family is the site of nurturant socialization for the newborn. Yet in preindustrial Europe and colonial America, people frequently turned over at least some of their children to non-relatives for socialization, while in many band-level groups socialization has traditionally taken place within the group as a whole. In many Native American societies infants might be fed by any lactating woman, rather than exclusively by the mother, while European noblewomen often hired wet nurses for their infants. We also know that many families do not nurture their newborns, witness the high rates of infanticide or abandonment in many historical periods; abandonment was often, however, a socially acceptable way of finding nurture for a newborn, and the family of procreation did not give up its claims or ties to the child.5

Donald Bender believes that we can salvage a universal definition of the family from this jumble of conflicting practices by simply studying the facts of kinship, regardless of the function or meaning of kinship to the people involved. Since people in all societies recognize kinship relationships and use these relationships as a basis for forming social groups, and because these relationships can be organized in only a certain number of logically possible ways, it is extremely useful to classify kinship groups in terms of structural types. Bender argues, for example, that the Yoruba of Ondo can be analyzed in terms of “de facto” families, even though they do not have “de jure” families and even though there are no social groups organized primarily around kinship relations. As Sylvia Yanagisako points out, however, this is analytically absurd. All societies recognize a whole series of categories — by age, height, weight, biological relationships, and so on — but if those categories do not organize or legitimize their social relationships in some way, they do not have much explanatory value for observers of the society. Where families are not legitimized, differentiated, and functional units, they can hardly be said to exist.6

But where families are legitimized, differentiated units fulfilling certain functions, they cannot be equated with other groups that may perform the same functions on different bases. This is the problem with the opposite approach to finding a universal definition of the family. The Journal of Home Economics has dropped kin relations altogether, defining the family “as a unit of intimate, transacting, and interdependent persons who share some values and goals, resources, responsibility for decisions, and have some commitment to one another over time.”7 Such a definition, however, makes the word meaningless as a unit of historical or sociological analysis. It excludes the element that has given the family, where it does have legal or moral meaning, such a powerful impact in ordering people's lives — the fact that it is both socially sanctioned and biologically explained.

In modern America, the “bounded” family is “a sphere of human relationships shaped by a state that recognizes Families as units that hold property, provide for care and welfare, and attend particularly to the young. …”8 A definition of family that goes beyond kinship or marital relationships is hence attractive to those who wish to extend welfare services and legal rights to units currently denied them by the modern state. But the attempt to extend those rights has generated enormous controversy, which will not be resolved by blithely defining the dispute out of existence. Moreover, it is worth noting that while the move to make, for example, gay households eligible for family assistance is understandable in the current economic climate, it also represents a capitulation to the view that families are, universally, the only legitimate units for emotional commitments, long-term obligations, and social support.

The delineation of a unique place and idea as “the family,” and the assignment of exclusive emotional, legal, or spatial rights to that unit, is not a universal phenomenon. The Zinacantecos of southern Mexico lack a word differentiating parents and children from other social groupings; instead, they identify the basic social unit as a “house.” The Yoruba of Ondo fail to define any social groupings purely in terms of kinship. Many band-level Societies disperse into small groups organized around a conjugal pair for one season of the year but spend the rest of the year in larger camps or compounds. The small units disappear into the larger at this time, and may be reconstituted with different members in the next season. Lila Leibowitz suggests that these “minimal dispersal units,” the pairs that ensure the physical reproduction of a group and constitute the smallest unit into which the group can divide and still survive, should not be confused with families. Such units may merely be personal arrangements for biological survival and reproduction, carrying no social sanctions and not functioning as an ideological symbol system. Indeed, a case can be made that some forms of kinship societies are not family systems, since everyone is considered as kin or treated as such and no smaller aggregation of individuals claims exclusive rights, activities, or emotions that demarcate its members from other groups.9

Yet if the family is not universal, and if its definition and functions vary widely, the fact remains that the concept of family is extremely widespread. Most societies have used this concept to establish certain kinds of interactions among people, and to prohibit others, on the basis of criteria that are defined as presocial, biologically natural, and therefore less susceptible of voluntary compliance or personal negotiation than other forms of interaction. This is what is fundamentally misleading about Carl Degler's assertion that the family “is at bottom nothing more than a relation between a man and a woman and their offspring.”10 Only some relations are accepted by society as families, and the constitution of a family involves the individuals within it in particular interactions with society at large and with other persons in society. An adequate concept of the family must take account of its central role in social as well as personal relationships, in societal as well as biological reproduction.

I argue that though most groups recognize marital and reproductive units, they develop a coherent definition of family only when distinctions other than those of gender, age, individual personality, and propinquity begin to be required to organize different kinds of duties and rights in the maintenance and reproduction of society. A family system represents a subdivision of relationships set up by kinship or location. It is a way of generating priorities or hierarchies in people's loyalties, obligations, and rights to labor or resources. As such, it is not surprising that the definitions and functions of the family vary as widely as do the obligations, rights, types of labor mobilization, and distribution of resources in different cultures.

Sylvia Yanagisako warns that it is impossible to “construct a precise, reduced definition for what are inherently complex, multifunctional institutions imbued with a diverse array of cultural principles and meanings.”11 However, we may be able to identify the kinds of issues and problems that are being addressed when a society does define the family. Despite wide variety in the organization and even the definition of families, all known societies of any significant size or complexity seem to use the concept to institutionalize and legitimize certain special, socially sanctioned relationships among various members of the group. And whatever unit a society or a subgroup within society defines as a family is the unit that determines the rights and obligations of its members in terms of inheritance, use of the prevailing set of resources, and initial “social placement” into the social configuration of labor and rewards.12 The determination of rights and obligations may be direct, as when production and distribution are organized through kin networks, or it may be indirect, as when birth into a particular family determines whether one will work for a living or control the labor of others, but in either case it seems to be one of a number of common patterns, rights, obligations, and associations that swirl around families in all societies.

In most non-state family systems, kinship connections to particular families or lineages involve people in sharply defined work and redistribution relationships, giving each individual definite obligations toward other members of society. Sex taboos, gender definitions, and marriage rules create interdependence and exchange, ensuring that all individuals are members of overlapping groups, with mutual and interpenetrating responsibilities and rights. Where classes arise, however, property ownership rather than blood ties increasingly becomes the primary determinant of social rights and obligations to labor, although many societies have gone through a prolonged period of conflict between the two competing systems of labor organization. As the state or the market establishes interactions in work, distribution, and consumption, the role of kinship becomes more constricted, a process that can be traced in the switch from exogamy to endogamy and the narrowing of sex and marriage taboos that once helped to organize social relationships into wider networks of exchange.

But even when property exchange and civil rule have almost totally replaced kinship as the organizational principle in economics and politics, families remain important in at least one key economic sense. If they do not organize or deploy labor directly, they still determine whether or not an individual belongs to a class that has access to labor through its control of political power or its ownership of property. Even today, despite the supposed usurpation of family functions by the market and the state, the family continues to play a critical role in determining one's place in the labor structure. Christopher Jencks, for example, has concluded that family background accounts for from 55 to 85 per cent of the earnings advantage of those who succeed economically in America, while the 1966 Coleman Report found that the family resources children brought to school affected their rates of learning more than the resources at the school itself. Family relations also continue to affect the distribution of work and its rewards; the high divorce rate in contemporary America simply provides one new basis for doing so. Divorce is the greatest single predictor of poverty for children and their mothers, channeling women and youth into the new areas of low-paid, part-time work that comprise the fastest growing sector of the American economy.13

Conceptualizing the Family

As one way of negotiating these analytical difficulties, I suggest that we see the family as the concrete expression of a socially sanctioned relationship between social and biological reproduction. It is a social institution that embodies a particular pattern of relationships among individuals as biological and social beings. But it is also an ideological concept through which people express their ideals about how biological and social reproduction ought to be coordinated. The family organizes and legitimizes the differential rights and duties associated with those resources and tasks, as well as providing an arena in which people try to cope with their different positions (gender along with class) in the larger social structure.

For most societies, the term “family” is not just a description but an explanation and a prescription. The concept of family seems to be a way of organizing or symbolizing certain kinds of group interactions in terms of personal relations, while at the same time it explains and enforces an individual's place in group interactions: “These things happen between unit A and unit B because a member of unit A is from a certain family”; “Because she occupies a certain position in a certain family, a member of unit A must behave toward unit B in a particular way.” Families create a group of people who are connected in particular ways to other groups, at the same time and as part of the same process as drawing boundaries between groups. The boundaries may be residential, economic, social, political, or psychological, but they always have to do with defining the rights and obligations of their members, not just toward each other within the family, but toward the larger social network. A family system is a tool for channeling people into the prevailing structure of obligations and rights, then attaching the tasks and rewards associated with that structure to a definition of self. The family is the physical and the mental place where we link our personal relationships to our social relationships, our reproductive relations to our productive ones.

Both as an institution and as a conception, the family mediates between people's definitions of themselves as individuals and as members of society. It is one of the main tools we use to understand and define ourselves in relation to the overarching social structure. The family regulates and limits the personal activities of its members while its members simultaneously shape, redirect, even dissolve and reconstruct the family to affect their role in the larger social network. The family is thus “a terrain of struggle,” both as a social unit, working with or against other groups in society, and as a changing set of personal interactions and conflicts over roles. Since the family is an explanatory and legitimizing device, a symbol system that functions as ideology, as well as a concrete constellation of relationships in the larger socioeconomic universe, its very definition is part of that struggle. That is why the family is always as much a political institution as a personal one.14

The family provides people with a way of assigning priorities to interpersonal interactions in the process of producing, consuming, and reproducing the necessities of life. As such, it is the key intermediary unit between the obligations and rights of its individual members and those of other social constructs. “As a social (and not a natural) construction,” Rapp remarks, “the family's boundaries are always decomposing and recomposing in continuous interaction with larger domains.”15 Yet people conceive of the family as a natural phenomenon, even where the fiction is blatantly obvious. It is thus a socially sanctioned relationship that explicitly rejects its social origins: a relationship whose legitimacy is attributed to biological and/or supernatural “facts.”

These “facts” are used to foster conformity to the roles defined by the relationship: families are presented as somehow prior to any social contract, as biologically natural or supernaturally ordained — a point powerfully reinforced by the prohibition of some sexual interactions within the family and the enforcement or strong support of others. All this works to link one's most intimate personal definitions — indeed, one's very sexuality — to social obligations and expectations. (This is not to say that the link is always harmonious or functional: a person's psychological identity or sexuality may become a victim of those rights or obligations, or a way of rejecting them.) The family is thus the place where we conceptualize ourselves in relation to the social structure, where we link a personal identity to our social identity, even if the family is not always the place where our personal identity is actually forged, and even if the link involves ambivalence or outright conflict.

The family is both a place and an idea. It is above all an idea, a “socially necessary illusion” about why the social division of obligations and rights is natural or just. This idea recruits or channels people into the places where social reproduction takes place. In modern America for example, Rapp argues, families recruit people into households.16 But the idea of “Family” is also used to share resources beyond households, to deny resources within households, and to label some households illegitimate agents of social reproduction. And the idea has some material base, for the family is also a place, distinct from household, from which people derive particular connections to rights, resources, and duties. It assigns individuals their initial position in the network of social reproduction on the basis of their imputed position in the scheme of biological reproduction, while it simultaneously offers an arena in which people can use changes in their social position to renegotiate their personal relations and biological definition.

The family's biological or supernatural legitimation is always loose enough to admit some personal flexibility into the construction or dissolution of families; thus the link between personal and social relations constitutes a feedback loop. As families assign people their initial place in the social order, so changes in people's place in the social order help them to reconstruct their families, while new family relationships help them to further affect their place in the social order. In some kin corporate societies the emergence of quite small differences in surpluses allowed certain patrilocal lineages to accumulate wives and children, whose labor enabled household heads to do the feasting and gift-giving that made them “big men.” The ability of “big men” to call in more labor and bride wealth eventually produced sharper socioeconomic stratification and new family arrangements. In modern America, the sons of men who succeeded in their careers partly through the unpaid work of their wives have discovered that the ability to avoid or shed a wife can sometimes greatly increase their financial solvency.

If these considerations have any merit, several conclusions must be drawn by family historians. First, the study of families must always be linked to a study of the whole mode of production of any given society. We should start “by identifying the important productive, ritual, political, and exchange transactions in a society and only then ... ask what kinds of kinship or locality-based units engage in these activities.” We must link family changes to transformations in the mode of production and “social reproduction,” including struggles over political ideologies and religious values. Michael Anderson suggests that “the student of family history must spend as much time exploring the wider culture and economy of a society as he or she spends investigating its familial behavior.”17

Second, we must understand there is no such thing as “the” family in any given society. Different subgroups, with different positions in the larger network of social relations, will construct and sanction different kinds of families. Families must be studied, then, in their historical, sociological, cultural, and psychological specificity. Yet because families are socially sanctioned, we cannot dissolve family history into the histories of multitudinous separate families. There is an ideal family type, generally codified in law and religion, and a normative prescription for how individuals should relate within the family. We need to study the interaction between the ideal and the reality, between the pressures of the dominant social institutions or classes and the needs of different subgroups in society. The slave family was not a simple imitation of the slave owner's family nor a helpless victim of the traffic in human beings. Neither, however, was it a self-actuated creation free from the constraints of white owners. Working-class families have preserved special class and ethnic heritages, yet they have also been greatly affected by the economic decisions and ideological pressures of their employers.

The correction to “history from the top down” is not to deny the impact of the top on the bottom but to admit the two-way nature of the penetration. Slave-owners' families also derived from the dialectic of slavery and cannot be understood without reference to the impact of slaves on white relations. Likewise, the organization of bourgeois families in the northern manufacturing centers, the cult of domesticity, and the contradictory tasks assigned to women took shape under the constraints of a society where entrepreneurs and upwardly mobile middle-class families were outnumbered by workers whom they wished to socialize and control yet from whom they also needed to insulate themselves.18

Third, defining the family as a socially sanctioned relationship between social and biological reproduction suggests that the key to understanding any family lies not in its size or structure, but in its articulation and interaction with both the larger social network and the changing roles or demands of its individual members. Household structure, family composition, and demography are useful pieces of data but on their own allow us to draw few significant conclusions about family life. More potentially productive is the study of the life cycle or life course, as proposed by Glen Elder, Tamara Hareven and others, which examines the “intersection” between individual life histories, family needs, and historical forces. Even this approach, however, tends to conceptualize family needs and historical forces as essentially separate phenomena. The concept of intersecting trajectories or “linkages” between parts of society reflects a functionalist model of society in which separate things arise independently and then get selected to “fit” in ways that make the system work. What we really need to do is approach families as organic parts of a total yet ever-changing network of social interactions in which equilibrium is never achieved.19

Our analytical tolerance of disequilibrium must also be extended to the internal life of the family. Since the family is a social construct through which individuals are assigned to — or resist assignment to — their position in the larger social network, we need to examine the struggle within families over roles, resources, power and autonomy.20 Because the family's assignments are made on the basis of imputed biological and sexual criteria, we need to pay greater attention to the link between the organization of production and consumption in society at large and the struggles within families over sexuality, reproduction, and gender roles. In Western history the ideology of family has long included a special association of women with domestic affairs. But because this association obscures a wide range of actual behavior, we need to pay particular attention to the impact of different family arrangements on women in their various familial and nonfamilial roles.

Fourth, we should avoid the temptation to label the family as a dependent or independent variable, as a malleable object acted upon by grand historical forces or an amazingly resilient institution that organizes itself to deflect the impact of social change, allowing its members to carve out their own culture. The family cannot be separated from the total network of social relations: when one changes the other changes, and the seeds of change may derive either from the larger structure or from the dynamics of family life within it.

We can recognize the family's impact on the larger structure, however, without elevating the family into a primary historical force. If the family is a socially sanctioned institution that coordinates biological and social reproduction, it follows that the family plays a fundamentally conservative social role, reproducing differences in the position of various groups vis-a-vis the system of production and distribution. This is not to say that the family cannot conserve values that challenge the dominant ones in society. Joseph Demartini has found that student activists of the early 1960s were not rebelling against their parents so much as extending or acting on shared values passed down to them by their parents.21 Ironically, the importance of family values in shaping student activism in this period may well have stemmed from the family's conservative role, for families were probably the one place of refuge for traditions of liberalism and resistance stifled in the 1950s.

To stress the conservative nature of families is also not to say that any individual family does not try to change or resist its position in the system. In order to do so effectively, however, the family normally mobilizes its members to take maximum advantage of their particular relationship to the means of production, which means perpetuating the system even while attempting to change its own place in it. A working-class family trying to earn enough money to buy a farm is not undermining the system of wage labor from which it is trying to escape: quite the contrary. The ghetto kin networks that pool and circulate resources are adapting rationally and effectively to the necessities of a poverty that stems from social rather than family pathologies, but they also hold back any particular individual who might threaten social solidarity for such “selfish” ends as going on in school. The same family that is an effective locus of resistance to ethnic or class oppression may achieve this by the ruthless suppression of the desires of its individual members, as so many immigrant girls, pulled out of school to work for the family, could testify. Indeed, the role of the family in “taking up the slack” during hard times, by increasing unpaid work at home to save money, suggests that the very strength of the family for working-class survival is its ability to fall back on the self-exploitation of its members.22

In focusing attention on the different ways that families are embedded in the specific social relations of society, we may be able to avoid grand historical pronouncements about the relationship of family history to industrialization or “modernization.” Thus we can examine how the social relations of an emerging market economy interacted with the ideology of the American Revolution and the demography of the middle class to produce the domestic family, without concluding that the private family with the woman at its domestic center is an inevitable component of any industrialization process. Nor need we postulate unilinear theories of social change whereby some grand historical family transformation begins in one sector of society and trickles down or seeps up to the rest. For the “modernization” of one sector, at least in a competitive economy or polity, often involves the devolution of another (as with the expansion of non-industrial work for women and the rise of illiteracy during the Industrial Revolution), while the same forces that impel one class to restrict its household size and family interactions may stimulate another to expand its household or extend contacts with kin.23

Bearing these considerations in mind, let us turn to a brief examination of some recent studies in Western family history. In tracing the historical evolution of Western families, historians have traditionally focused on two aspects of family life — structures and values — that entail different sources and different questions and, not surprisingly, often yield different answers. Discussing their findings, I will focus on the English case, since it is the evolution of English family forms that provides the most direct backdrop to the institutions and ideas brought to America by the dominant group of colonizers.

Western Family Structures

From the relative silence of traditional European literary sources about the nuclear family, historians and sociologists once posited a shift from extended to nuclear families in American and European history. Their writing produced a widespread impression that the nuclear family was a modern development, a product of industrialization, and that preindustrial populations lived in large extended families. During the 1960s, however, the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, under the leadership of Peter Laslett, carefully quantified all available parish records in England since the sixteenth century. They found that, from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries, mean household size remained fairly constant at about 4.75, and that even the larger households contained relatively few kin, servants being the main variable in size differences. After examining other European and Asian countries as well, the researchers concluded: It is simply untrue, as far as we can yet tell, that there was ever a time or place when the complex family was the universal background to the ordinary lives of ordinary people.” Even more devastating to the idea that the nuclear family was a result of industrialization was the finding that the proportion of extended families actually increased in industrial towns during the mid nineteenth century.24

The belief that there has been a historical evolution from an extended to a nuclear family would seem false, but one should not infer from this that family structure is historically invariant. Lutz Berkner, for example, has pointed out that the statistical predominance of nuclear families in any given census, or group of censuses, may conceal a developmental cycle such as that of the patrilocal stem family, common in many peasant societies, in which a young couple marry and spend their early life together in an extended family, living with the man's parents. When the man's parents die, the couple succeed to the house and spend their middle years in a nuclear family, but when one of their sons marries and brings his wife into the household the family becomes extended again. A substantial majority of households may be nuclear at any given time, but nearly all of them will nonetheless pass through an extended stage. Although Berkner did not claim that preindustrial England had a stem family system, he certainly threw doubt on the universality of the nuclear family in European history.25

Other authors have pointed to the frequency of patrilocal joint families — involving co-residence of married brothers and their families — in parts of Western Europe prior to 1550 and in Eastern Europe into the nineteenth century. Nuclear families accounted for only about 50 percent of the households in Southern France during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, though they were overwhelmingly preponderant in Northern France at the same time. In some serf settlements in Great Russia, extended and multiple families predominated during the late 1800s and early 1900s. David Herlihy argues that in the ancient Mediterranean world households and families “differed so widely from each other that they could not be encompassed in a single system of social analysis, or utilized as a useful unit of social measurement.” In light of these facts — to say nothing of evidence that many prehistoric Europeans lived in extended families — Laslett has modified his early contention that the human family, if not necessarily the household, must always have been small and almost always nuclear. He now merely calls attention to “the extent to which the single family household prevails in England, the Low Countries, and northern France, and has since the sixteenth century.”26

We should not, however, exaggerate the early “modernity” of these families. As Jean-Louis Flandrin has commented, averaging households obscures the specific preindustrial pattern of “dominant large households and dependent small ones.” Laslett's original essay admitted that “a majority of all persons lived in the larger households in traditional England, those above six persons in size, in spite of the fact that only a third of all households were in this category and that the overall MHS mean household size was less than five.” We should also note that Laslett excluded lodgers from the computation of household size, while conceding that their numbers certainly exceeded those of resident kinfolk “and may have been of the same order as servants.” In light of these considerations we must conclude that seventeenth-century English families were far from modern, despite some quantitative similarities: The poor lived in truncated families, often without even their very young children; the richer elements — and many of the younger lower classes who worked as servants — lived in large households where few distinctions were made between the biological family and the rest of the residents.27

From 1650 to 1749 there was a decline in the number of servants in the average English household but a rise in the number of kin, especially offspring. From 1749 to 1821 this trend continued, with a sharper fall in the number of servants. By 1851, however, the incidence of lodging had increased (though the increase was entirely accounted for by the urban areas rather than a change in rural areas). After the 1850s there was a sharp drop-off in both lodgers and number of offspring, resulting in substantially smaller households. In 1947 (an atypical year, however, due to the postwar housing shortage), the co-resident kin group, beyond the nuclear unit, was actually larger than in any of the earlier periods.28

These trends impeach the view that England moved from an extended to a nuclear family system. Looked at in one way, however, they do testify to an increased emphasis on the nuclear family. The move from servants to lodgers, who were less likely to be involved in daily family activities, can be combined with data about changes in morality, architecture, and etiquette to suggest a tendency for the nuclear family to close ranks and seek more privacy. And it is worth noting that by 1947, even though the number of co-resident kin was greater, the range of kin represented in households had narrowed to immediate relatives, from the previous situation in which the wider kin group was more proportionally represented when kin were present.29

It is difficult to tell whether changes in family structure over time represent a change in family forms among all classes, a change in the distribution of classes (giving greater statistical prominence to groups that might have displayed the same family characteristics in the earlier period), or a switching around of family strategies within a shifting class and regional configuration. In their most recent work, the Cambridge Group identify four general family patterns, which they associate with different regions of Europe: the West, West/central or middle, Mediterranean, and East. The Western pattern involves neolocalism (establishment of a new household upon marriage), households centered on a single family (with extra labor needs met by adding servants or apprentices rather than kin), and a marriage pattern first described by Hajnal in 1965; late marriage and a high proportion of the population never marrying at all. This Western form is closely associated with a high degree of independence in the way that a household head can dispose of land, labor, or other resources and, especially in England, with the relatively weak “concept of a family plot or even a family house.”30

Yet Laslett reports that households of laborers, in all the regions surveyed by the Cambridge Group, “have to be placed under the heading ‘west’ in most relevant particulars,” while in “every reproductive demographic particular ... they were inclined to conform to the English model.” This suggests the possibility that some changes in a society's “family system” may actually be changes in its class system — or in the class origins of the sources we have available. Renate Bridenthal points out that our sources for family life in places such as preindustrial Europe are those left by the literate upper classes, about themselves, whereas in twentieth-century America we have almost no information on the very rich but reams of statistics kept by the middle class on sections of the working class and the poor. Alternatively, however, the same class may employ different family strategies as its relation with other classes, the ecology, or the state changes. Thus R.M. Smith has found that in the thirteenth century, middling villagers had more interdependent and frequent relations with kin and neighbors than did the richest and poorest members of the village, whereas in the twentieth century the middle class has tended to have fewer such relations than the rich or the poor.31

It is also difficult to make unilinear statements about the direction of change. David Herlihy has found, for example, that among the upper classes of Italy a more extended family evolved in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a time when some other families were contracting to a supposedly more “modern” form. A recent study of French wine growers found that the number of extended households in Cruzy increased between 1836 and 1866. After the 1880s there was a “renuclearization” of the household among the lower classes but this allowed the landowning classes to sustain a further increase in complex households, as they were then better able to mobilize the labor of their lower-class neighbors. Household composition in industrial English and American towns also grew more complex at the very time that socially dominant views of the ideal family stressed its increasingly nuclear character.32

Western Family Structures and Productive Relations

Changes in family and household forms are the result of an extremely complex commingling of class dynamics, ecological imperatives, cultural heritage, economic factors, and political relations. Certain broad generalizations can be made about some associations between socioeconomic conditions and family structure. As we shall see below, however, similar structures may have very different meanings for both the individual and the social network, depending upon a host of other factors.

In general, large, stable, co-residential extended families tend to be found where the supply of labor is inelastic and where collective work groups and mutual aid are required in diversified production and distribution. These families may take matrilocal or patrilocal forms, depending upon the sexual division of labor and the advantages of concentrating related males or females in the organization of production.

The forces of production and distribution, the supply of resources, and the concept of territory must be developed enough to support the exploitation of a given area by a relatively large and immobile group that holds a special association with the place or the resources due to descent from a common ancestor. Yet these factors must not be so developed as to offer opportunities and incentive for the conjugal family to exploit them independently or in competition with the rest of the group, or for the family head to alienate the property. Under such circumstances there is every reason for each smaller unit within the extended family to contribute labor or goods to the common store. Such families, then, are most likely to occur as a dominant social type among pre-state and non-market societies where there is corporate control of land or other resources, where land or resources are relatively plentiful, and where there are few pressures to increase productivity. A number of authors have documented an association of co-residential extended families with widely scattered resources or tasks, when the corporate group requires simultaneous labor in many different places or at a variety of tasks. So long as such labor cannot be mobilized through slavery or wage-work, extended family households are the most effective way of allowing the group to engage in complex, simultaneous tasks.33

Extended family households may, however, also be found in certain classes or regions of societies with more developed market and state systems where self-generation of labor or capital allows a group to carve out a specialized niche in the mode of production. Elites may be able to protect themselves from rivals connected to a state apparatus by using extended family ties to make political and military alliances; hence the protracted conflict between aristocratic kin groups and monarchs in medieval Europe. Where institutional sources of security and finance are not available, emerging economic groups, such as the medieval merchants of Genoa, can use complex households as a base for developing early forms of diversified trade and manufactures. When income opportunities are irregular but frequent, or uniformly if only occasionally distributed, multiple-family households seem to maximize the possibilities for achieving income and redistributing resources. Such households are frequently found in areas where people exist by a combination of wage-earning and household production. The availability of waged work for some household members combines with the benefits of pooling labor for domestic production to make such arrangements possible; the instability and low wages of the work make them necessary. Thus there seems to be a pattern in which multiple-family households appear in periods of transition from subsistence production to wage-labor, helping people to cope with the uneven and combined development of market and household production. Multiple-family households also seem to have represented an effective form of survival for eighteenth-century Eastern European serfs after the reimposition of servile restrictions in response to agricultural demand from Western Europe. When household production is not a possibility, extended families among the poor may not have the resources for co-residence but may nevertheless rely on pooling networks outside the household.34

Joint patrilocal families, with several brothers and their spouses residing together, were common in parts of Italy and France before 1550, as well as in many Eastern European communities up to the nineteenth century. Where output could be increased considerably by adding land, animals, and other investments to an already existing productive unit, the joint family served to concentrate and mobilize the labor of male members. Joint families have been found frequently along frontiers, either internal or external, in areas of extensive plow cultivation where land is more available then labor, and in newly developed commercial sectors where no institutional means of drawing on new capital and labor supplies yet exist.35

But the same possibilities of expanding output that call this form into existence also introduce constant strains into the relationship and put an upper limit on the number of conjugal families that will reside together. Robert Wheaton has pointed out that unless there is “a general equality between the resources of the individual nuclear components” of this family, the wealthier unit or units will have an incentive to secede. In other words, this family type normally thrives only as long as there is a relatively predictable economic situation in which rapid changes in fortune are unlikely for the separate conjugal units involved in the joint family.36

Given an abundance of non-family labor or capital, but only a fixed amount of land, the joint family appears less frequently. The same classes that utilize the joint family in the situation described above may in these circumstances prefer the stem family, to prevent the dispersal of land. “Arranged in order to select and establish a favored heir,” the stem family serves “the interests of the rather narrow vertical lineage formed by attaching one younger couple to the patriarch's household, while discarding or disfavoring the other offspring.”37

The nuclear family has tended to emerge as the residential norm whenever economic or political conditions have encouraged or necessitated production and distribution by relatively smaller groups. “Small households,” comment Wilk and Rathje, “have the advantage of mobility, and are well adapted to make intensive use of limited resources through linear scheduling of labor.” Stephen Weinberger has found that in medieval Provence, as peasants gained more control over their land so that individual activity yielded more variable returns, they tended to dissociate themselves from the extended family, which had a high degree of solidarity but lacked flexibility in responding to rapid changes in economic opportunities. The nuclear family is linked to individualistic economic pursuits, especially where accumulation and investment are necessary for economic advancement but the productive process does not require large amounts of capital. It is also found where relatively stable employment consistently favors one category of household member, such as men.38 States have tended to favor nuclear family households, both for economic reasons (taxation and labor mobilization) and political ones (the greater ease of controlling an individual family unit as opposed to a united extended family).

In Western Europe, the nuclear-family household was historically associated with a high degree of independence for the household head and the connected possibility of rapid economic mobility, either upward or downward. Laslett's figures show that a household head in the West could often be described as a pauper, whereas this was “never” true in the Mediterranean and Eastern cases, where households were property-owning corporations: “The family plot in England was to a surprising extent disposable by the man who had control of it.” Alan Macfarlane comments that “one of the peculiarities of England from at least the thirteenth century was that parents could . . . disinherit their children.” The weakness of corporate control, of course, both contributed to and was accelerated by the early development of commerce and wage-labor in England.39

It will be noted that these generalizations are hedged with qualifications and restrictions, for bald statements about the necessary association between any mode of production and a particular family structure are suspect. This is true, first, because “a particular productive enterprise can be accomplished by a variety of productive units,” depending on the technical organization of production, the social and economic relations under which it is conducted, and the political, legal, and ideological systems that have evolved in a culture.40 Second, any particular mode of production, especially one based on class differences, will produce a number of different household structures, whose necessary relationship to the mode of production derives not from their internal forms but from their articulation with each other. Thus the extended households of wealthy families, from sixteenth-century English estates to nineteenth-century Cheyenne Indians and Languedoc winegrowers, could not exist without the small households of poor families.

Used cautiously, however, studies of the relation between productive activities and household structure are certainly a starting point. Recent work on fertility rates reveals the value of such investigation. Traditionally, preindustrial populations were thought to have maintained themselves by balancing high, though fluctuating, death rates with high and fairly constant birth rates. Population growth, in this analysis, occurred when death rates fell and birth rates continued at the previous high level. This was said to explain the population explosion associated with the initial stages of the Industrial Revolution, while the drop in family size in the nineteenth century was thought to result when modern contraception finally allowed birth rates to adjust to low mortality rates.

It now appears, however, that preindustrial birth rates were extraordinarily flexible, ranging from a high of 55 to 60 per 1,000 in eighteenth-century America to a low of 15 per 1,000 in Iceland in the first decade of that century. A fall in the death rate often led to exceedingly rapid homeostatic adjustments in the birth rate, as happened in eighteenth-century France. Where population growth did occur elsewhere in Western Europe, it was achieved by an increase in the birth rate as well as a decline in the death rate. In some areas the death rate actually rose, so that population growth was wholly attributable to a rising birth rate. Furthermore, the nineteenth-century fall in the birth rate began before the spread of modern contraceptive techniques. It therefore seems more logical to connect changes in the rate of population growth to social conditions rather than to death rates or birth control alone.41

In England, according to the most recent reconstruction of national demographic trends, population grew from the mid sixteenth to the mid seventeenth century, and then fell off, not regaining its mid-seventeenth century peak until the early eighteenth century. The primary factor affecting population growth was variation in patterns of marriage formation. The authors argue that marriage formation rates were in turn responsive to changes in the real wage, though only after a significant delay and only prior to the mid-nineteenth century. Their data are valuable in showing the mutual impact of economic trends and family strategies in the preindustrial world, but it may well understate the responsiveness of personal reproduction to changes in social production. Wrigley and Schofield reject the theory that demand for labor affects population rates, except in the very long run, because they define that demand as the aggregate need for labor in society as a whole and fail to find any harmonious regulation between the aggregate demand for labor and marriage or fertility rates. 42

But the impact of changes in the social demand for labor on personal reproduction rates has to be considered in light of the family's mediating role between them. Under some circumstances the family may experience a national decrease in demand for labor as an increase in its own demand, lower wages for the individual worker making it necessary to have more workers per family. Thus there is no necessary contradiction in the fact that the fall in real wages in the late sixteenth century, and possibly in the eighteenth century too, was accompanied by a fall in the age of marriage and a rise in fertility. Much depends on the qualitative demand for labor, which determines what it will cost the family to produce new workers, as well as the quantitative demand. If a fall in aggregate demand for labor is accompanied by a fall in the cost of producing labor, early marriage and high fertility are an understandable response. Conversely, the rise in the age of marriage in the nineteenth century may have been associated with the shift into occupations requiring longer and more expensive periods of training.43

David Levine's detailed study of four English villages in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries demonstrates that different fertility rates among villages, and occupational variations in fertility within villages, can be explained by changes in both the type and the total amount of labor required within different occupations. As eighteenth-century economic developments increased the number of families dependent upon commodity production (both in the industrializing areas and in the centers of rural protoindustrialization), the relationship between people's work and their demography changed. Traditional incentives to delay marriage disappeared, while at the same time children increasingly became an economic asset to their families: in the protoindustrial economy they were a main source of labor for the family enterprise and in the wage economy they could be put out to work early, often reaching their peak earning capacity by the end of their teens. During the Industrial Revolution fertility increased rapidly in industrial centers where there was a high demand for unskilled labor, and even more rapidly in agricultural sectors producing for the urban market or areas of handicraft production supplying industrial centers. These non-mechanized sectors of the economy could respond to the increased demand (and the increased competition) only by increasing labor inputs at the family level.44

A high-fertility demographic strategy, of course, involved tremendous risks for protoindustrial and early industrial households, as an economic slump could catch them with more dependants than workers. A rational population strategy for one family, moreover, might exacerbate unemployment in the class as a whole: having numerous children was nevertheless the surest way to maximize the family's productive capacity. Mahmood Mamdani has reported a similar dynamic in population growth in twentieth-century India, and other studies confirm the basic rationality of dependent classes or countries adopting a high-fertility strategy, despite its long-range ecological effects. Only with growing complexity in the job market, a rising wage rate for the household head, and the increasing cost of producing labor as openings occur in more skilled occupations does it make sense for lower-class families to curtail their fertility.45

In America, rapid population growth in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was clearly connected to demand for labor. Growth rates were greatest in those areas just behind the frontier — still so sparsely settled that land was available, undeveloped enough that the primary labor requirements were for labor that did not entail a long period of nonproductive training, but developed enough to be able to market any surplus resulting from more labor inputs. In the nineteenth century, massive immigration filled US labor needs and native fertility declined, following a substitution effect also evident in the eighteenth-century South, where the smallest white families were found in those regions with the largest number of slaves per household. But Richard Easterlin has demonstrated that variations in immigration rates were themselves dependent on changes in the demand for labor.46