"Le Corbusier’s Ideal is a Barracks"

While the Pompidou Centre is paying homage to Le Corbusier, a group of historians and writers reminds us that his works were coloured throughout by his totalitarian and fascist views. First published in Le Monde. Translated by David Broder.

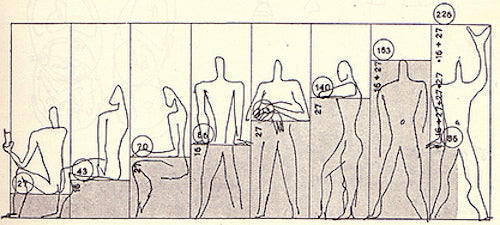

From Corbusier's Le Modulor 1.

At the same moment that the Pompidou Centre inaugurated its exhibition on Le Corbusier in April 2015, there appeared three books looking back to the architect’s fascist propensities. Startled as reality suddenly broke through, the organisers decided to refer the question to a conference that would be held in late 2016, as did indeed take place on 23-24 November of this year. However, certain authors very critical of Le Corbusier were not allowed to participate. And anyway, why organise a conference when we need only read the numerous writings of the author of La Ville radieuse to be struck by the constancy of his totalitarian intentions? The conference amounted to nothing more than a sham.

Le Corbusier was an immense, brilliant ideologue. A militant of the fascistic or fascist far Right for over twenty years, and a Vichyite, he also admired and looked eagerly towards Mussolini, Salazar and Primo de Rivera — not to forget Hitler. The starting point of his worldview was above all "order." Indeed, Le Corbusier spoke of a "fatal order" as part of a worldview that was itself sustained by a deep biological mysticism: the eugenicist project of fabricating an athletic, healthy body; a radical purifying hygienism (Le Corbusier founded the artistic current "Purism"); the fear of the degeneration or rotting of bodies linked to the development of the modern city, made ill by its uncontrolled machinism ("Trying to cure the ills of the present-day social body? This is exhausting labour — an ineffective toil. There is decrepitude, old age, twilight, the end of an expired civilisation. We must fit out the new machinist civilisation"). This went together with an organicist conception of society ("this means not changing the décor, but a biological revolution. The [architectural] new being must be whole, one") and of the city, identified with a giant body ("Society resembles man, the built domain of the nation must resemble the human body"). The city was composed not of individuals but of cells, often deemed dangerous and a threat to the race ("a city is a biology").

Anti-Semitism

Le Corbusier advanced anti-Semitic arguments — not very many times, but repeatedly and without any equivocation — up to and during the Second World War. He was fascinated by hierarchy, developing a certain aversion to the poor and workers as well as holding women in contempt, wanting to send them back into the home. He was fundamentally anti-republican. For him human rights did not exist, and he considered democratic life worthless and ineffective. In its place he wanted to establish a technobiological realm, with a view to fabricating a new race. The physical constraint exercised by the urban plan would replace the laws deliberated in parliament. As he put it, this was "the dictator plan."

In Le Corbusier we find themes like the great end goal underpinned by a tabula rasa of history and all its physical and material traces; the destruction of the old city, followed by an implacable, brutal, cold urban reconstruction; the wild-eyed phobia of illnesses transmitted by strangers; his admiration for the authoritarian state; identification with the leader… Such themes together made up a social project in which his architecture (with its five points: the free plan, concrete stilts [pilotis], the free façade, long wide windows, the roof-terrace) and urbanism (its four functions: inhabitation, work, recreation in free time, circulation) also made up a system. Their implementation relied on the generalised standardisation of objects and of construction; the rigid mathematisation and geometrisation of space and its corollary in the fabrication an ideal "proportioned" body — the famous Modulor. This invariant, partly reified psychophysiological entity was an instrument of calculation incarnate, allowing the "proportioned" body to be rendered consistent with the dimensions of the spaces of constraint and subjection, from the habitation-cell to the functionalist space by way of the "standard-size habitation unit." A priori this meant the tough, white, virile male in the image of the Modulor, whose bodily archetype stands side by side with the sculptures of Arno Breker and Joseph Thorak, the Third Reich’s two official sculptors and themselves fervent Nazis. A rather impressive and always-dominating body. The Modulor is slender, has a strong stature, narrow hips, a head with no face — though sometimes a single eye instead — and no sexual organs; conversely, it has an enormous hand. It is naked — across the ages the symbol of strength combined with beauty — and an image close to the Third Reich aesthetic that itself emerged from a totalitarian interpretation of the canons of Greek beauty.

Le Corbusier wrote in autumn 1939 of "a ray of good news: Hitler demands simple materials, seeking thereby to return to tradition to rediscover the robust health that can be discovered in any race. For Berlin had brought into the world the troubling architecture of an avowed 'modernism,' so troubling that it can sometimes entail hateful thoughts." The modernism that so troubled the architect was that of the expressionist painters ("of truly nauseating stench," "morbid, disreputable") and probably that of the housing blocks conceived by Martin Wagner, Walter Gropius and Bruno Taut under the Weimar Republic. Better Hitler and Mussolini ("Italy has brought into the world a living and seductive fascist style") than social democracy.

"Human anthill"

Neither did Le Corbusier ever have any sympathy with — or still less empathy toward — workers and the poor. "The people? Like bees or ants it comes and goes, leaves and returns: it nestles in tiny alveoli and busies itself in narrow and complex corridors." He saw the pooling of individuals in present-day cities as a "human anthill," and the future man of the radiant city as "constructed being, cemented biologies"; he went as far to speak of "man, the bloke with two feet, a head and a heart, an ant or a bee enslaved to the law of living in a box, a compartment behind a window." Le Corbusier’s ideal of habitation corresponded to ideas of shutting, occlusion, confinement: the barracks model, endowed with a certain degree of comfort but a barracks all the same. Le Corbusier was explicit about those recalcitrant toward his project: "Our cities are engorged with a parasite population. Our cities will purify themselves." Plastic purism, political purges…

The sculpted corpse of the massive Modulor was associated with the reduced dimensions of the cramped living space divided up among the mass: that of the existenzminimum (the ceiling just 2.26 metres from the floor, and the child’s partitioned room, 1.5 metres across). The body is held or contained in the different spaces of the cell by compression, constraint and ultimately submission. The body is compressed by its surroundings. The objective is to hold the body cloistered in a habitation cell, "the square box," and the habitation unit surrounding these cells. The body is almost gripped by the built environment. Even when the inhabitant wants to extract herself from it, she immediately comes across the sporting terrain situated at "the foot of the blocks." Beyond that, bodies become anonymous particles projected into the flux of incessant circulation, captured and integrated into the incessant urban flow, with its multiple gears.

For Le Corbusier, from the 1920s onward, architecture and urbanism belonged to one same political order. His 3 million inhabitant Contemporary City or his Plan Voisin — with an architecture limited to sky scrapers and blocks alone, entirely in glass and concrete, were its direct material projections. "Dwellings, the city," Le Corbusier wrote, "are a single whole, one same manifestation of unity": "Urbanism enters into architecture and architecture into urbanism." "So I bring architecture and urbanism into a single notion, a single solidarity. Architecture in everything, urbanism in everything."

With Le Corbusier the city loses all its organic and plastic quality. It becomes urbanism, meaning the anxiety-inducing organisation of life, the difficult arrangement of the flows of an uninterrupted flows of traffic. "Dominated by a sky spreading everywhere," Le Corbusier worried, "I was very anxious that the immense voids I created in our imaginary city would be 'dead,' that ennui would reign and panic would grip its inhabitants." This means a strict and orthonormal spatial order imposed by an overhanging architecture of skyscrapers lost in the clouds and blocks stacked out to infinity, all of them perfectly identical. The city disappears in favour of a uni-dimensional uniformity.

Le Corbusier’s leitmotiv is the abolition of the "street-corridor." He compares the traditional street to a "channel," a "fissure," making up part of the "residue of the centuries." The radiant city must remain circulating, without any obstacles, and is pierced or perforated from end to end by motorways for cars. The sky itself is summoned to play the role of a space for the circulation of airplanes: an airport is established right in the heart of the radiant city. This abolition of streets corresponds to the fierce will to efface the history for which streets constitute the material basis and physical imprint. As a site of passage, of encounters, of possible meetings and sometimes extensive time spent in the squares, the street makes up part of the city’s living character: it is part of its primary substance. And Le Corbusier wanted to destroy that, too.

Simone Brott, historian, Australia; Xavier de Jarcy, journalist and writer, France; Daniel de Roulet, writer, Switzerland; Marc Perelman, architect, France; Zeev Sternhell, historian, Israel.