A Closed Loop: Sex Work, Violence and Criminalisation

Molly Smith (@pastachips) responds to the tensions between policing and protection of sex workers following the release of video footage of sex workers being escorted from their Belfast home into a police van, while a hate mob jeers at them. She argues that criminalisation and policing, often racialised, create the conditions for violence against sex workers to thrive, which is then used to justify further policing and criminalisation.

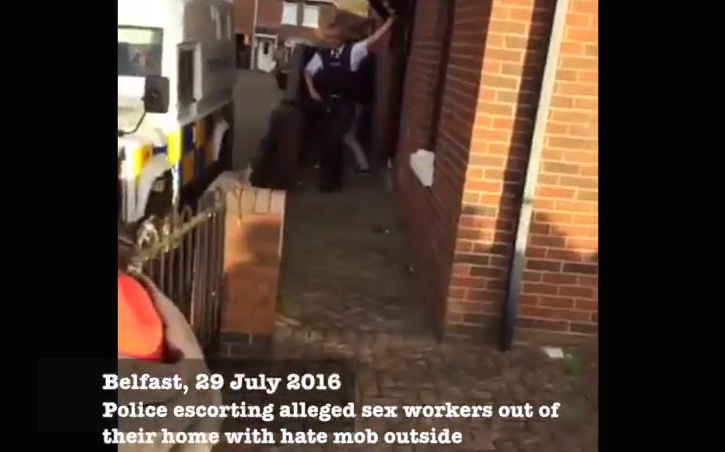

Last Friday, on the afternoon of the 29th July, a large, angry crowd gathered in Belfast outside an unremarkable semi-detached house. In shaky mobile phone footage, since uploaded to YouTube, perhaps a hundred people are visible – men, women, small children. They are shouting and jeering, and the jeers grow markedly louder as women appear from a side door of the house and are hustled by the waiting police into the militarised police van used in Northern Ireland. You can hear people in the crowd shout “nasty fucking whores”. The women are suspected to be sex workers.

There is a lot to unpack in this scene. The footage is hard to watch. Unlike videos where the person capturing the scene is aware that they are documenting something horrifying, this clip seems to have been filmed by a participant: a cheerful memento of a summer day. The presence of small children reinforces the troubling sense that this is both an act of community violence and an event attendees considered a family day out.

In Playing the Whore, Melissa Gira Grant writes about vigilantes who post videos of suspected sex workers online, noting that for those who film and post these videos, “the camera isn’t just a tool for producing evidence: it’s his cover for harassing women he believes are selling sex, pinning a record on them online even when the law will not”. Looking at photos taken during the Soho raids, for example – women dragged into the street in their underwear, a line of women all attempting to shield their faces from the camera – gives the unsettling sense of participating in or re-enacting this violence again, something akin perhaps to viewing ‘revenge porn’. The Belfast video has been posted by a sex worker support organisation, which speaks to a tension here: to ‘prove’, document or discuss this violence, you must share the images – in a small way, you must also take part in it. Visibility can be a mode of violence against sex workers (think of those faux-outraged tabloid front pages: ‘EXPOSED: NANNY HOOKER SHOCK’), which makes rendering this violence visible a double-edged sword – though to be clear, I’m grateful to Ugly Mugs Ireland for their work in documenting this incident and attempting to push it onto the agenda.

Community violence against sex workers is not uncommon, although most often it is directed at street-based workers. In Sex Work and Violence in Britain, Hilary Kinnel details vigilantism throughout the 1980s and 1990s against street-based sex workers, their clients, and anyone assumed to be in any way associated with the sex trade. Racist ideas about “pimps” meant that black people were particular targets. In Balsall Heath, Kinnel records women attacked, followed or threatened by groups of residents: “some sex workers were … still suffering abuse and harassment over three years after the vigilantism started … One woman received anonymous letters threatening to burn her out, had her windows smashed, an airgun fired into her house and lighted fireworks pushed through her letter box”. Despite this, the events on Balsall Heath have been widely understood as non-violent, and Kinnel notes that the 2004 Home Office report Paying the Price praises ‘the Balsall model’ as a successful “community intervention”. David Cameron even credited Balsall Heath as inspiration for his ‘Big Society.’

Northern Ireland, like the rest of the UK, has seen a sharp rise in reports of racist hate crime since the EU referendum. It isn’t yet clear whether the women being jeered out of their house were migrant women, women of colour, or both. But it will be grimly unsurprising if it turns out that they are. Whorephobic attitudes and policies are intimately tied to xenophobia and racism. Norway’s 2009 introduction of the Nordic model (or ‘sex buyer law’) followed a racist moral panic about black street-based sex workers, particularly Nigerian women. Despite the law’s purported humanitarian basis, it was at some level understood by policymakers and the Norwegian public to entail a punitive response to these women of colour, who were presented as ‘threatening’ Norwegian men. As was implicitly promised, the Nordic model in Norway is disproportionately enforced against black and migrant sex workers.

In 2013, the Scottish Parliament’s Cross Party Group on Human Trafficking met with the creator of an app that enabled members of the public to instantly call immigration police on anyone they suspected of being a ‘trafficking victim’. Within the app, the category of “trafficking victim” is constructed as primarily referring to people suspected of selling sex: the meeting notes detail that one of the five signs to identify such victims is if they appear to be “advertising themselves for money”. The listed indicators for trafficking cannot explicitly say “prostitution”, since the app is in part aimed at children – like the Belfast crowd’s inclusion of small children, the app is considered child-appropriate.

An app is more discreet and modern than jeering outside a Belfast house, but it isn’t hard to see how this kind of trafficking “concern”, and the legitimacy with which it is imbued by politicians, is a veneer on something very disquieting. Push the button, call the border police. Last year, amid alarm over trafficking, the Stormont Assembly brought the Nordic model to Belfast in June.

Another element at play here is misogyny, of course. Northern Ireland has some of the most punitive anti-abortion laws in Europe. Watching the Belfast footage, the presence of women in the angry crowd evokes women on “pro-life” demonstrations. Women are habitual enforcers or enactors of patriarchal violence targeted at other women. “Keep abortion illegal – women are safer without it”. “End prostitution now”. Notably, the Nordic model intensifies stigma against sex workers, increasing the belief – particularly among women – that people who sell sex deserve criminalisation:“The Swedes and foremost Swedish women would even like to criminalise the sale of sex.” The sex buyer law has only been in place for fourteen months in Northern Ireland, but it was pushed for years prior to its implementation by the hard-right misogynist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

Ultimately, the women in the patchy video footage from Belfast, hurried into the police vans, their bodies and faces shielded from the hostile crowd both by their coats and by the police officers flanking them, suggest some key tensions between policing and protection. After all, despite repeated claims that the Nordic model ‘decriminalises sellers’, if these women were working collectively from the flat they were chased from, they may well be being protectively, kindly, gently guided into militarized police vans – to be prosecuted.

The Belfast scene is a stark reminder that criminalisation, and the policing that accompanies it, create the conditions for violence against sex workers to thrive, however gentle individual police officers may be. The violence that sex workers suffer then becomes justification for further policing and criminalisation: it becomes the ‘the answer’ to the problem of sex trade violence. Like a video clip from a mobile phone, the pattern repeats in a closed loop.