Five Book Plan: Radical Poetry

It's painful to choose only five books for a topic that feels like what made your life your life. Even bracketing my own comrades and contemporaries, and recognizing my own limits regarding translation and other national traditions, there are six dozen I would want to name, Audre Lorde, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Roque Dalton, Sonia Sanchez, Bertolt Brecht, Cesar Vallejo, Xu Lizhi, Robert Desnos, Adrienne Rich, so many more, even Saint-Just for saying "Happiness is a new idea in Europe." It would be echoed in my favorite piece of graffiti from the Sorbonne occupation: "ten days of happiness already." It's a start.

Diane DiPrima, Revolutionary Letters (City Lights 1971, Last Gasp 2007)

The georgic, a poem explaining practical matters such as agriculture and beekeeping, is more or less lost to history. This lends the series of poems a deep uncanniness. First composed between 1968-71 and extended over following years increasingly including eco-feminist concerns, they comprise the great modern georgic. The practical matters include insurgent fighting, from the local (“store water; make a point of filling your bathtub / at the first news of trouble: they turned off the water / in the 4th ward for a whole day during the Newark riots”) to the more general: “when you seize a town, a campus, get hold of the power / stations, the water, the transportation, / forget to negotiate, forget how / to negotiate, don’t wait for De Gaulle or Kirk / to abdicate, they won’t, you are not / ‘demonstrating’ you are fighting / a war, fight to win.” The entire book is rifted with moments that in their directness cut through a lot of bullshit. As to whether 1968 was a revolutionary situation, or is a toad crouching on the struggles of the present, I will let others fight it out. That poems like this could be written out of that moment feels important to me. Against the often modernist, often liberal values of complexity, uncertainty, opacity, I don’t mind a good, simple lesson every now and then: “take what you need, ‘it’s free / because it’s yours’.

Amiri Baraka, Transbluesency: The Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones (1961-1995) (Marsilio Publishers 1995)

Baraka moved through many positions in his life: downtown denizen, Black Arts founder, cultural and later black nationalist, Marxist internationalist, poet laureate of New Jersey, and much more. There is a way one could tell the history of the postwar United States through him and his poetry and his plays and essays. But it would be an oppositional history, a black history, a history lacking the compromises that are the oxygen of power. Baraka had moments of deeply problematic writing that it would be odious to ignore. But in the same moments and many others he composed some of the most vital and brilliant and relentlessly revolutionary poetry on offer, none of it better remembered than the passage from “Black People!” which anticipates the DiPrima passage above: “...you cant steal nothin from a white man, he’s already stole it he owes you anything you want, even his life. All the stores will open if you will say the magic words. The magic words are: Up against the wall motherfucker this is a stick up!” I believe this is what the theorists call a speech act.

Michael Demson, Masks of Anarchy: The Story of a Radical Poem, from Percy Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire (Verso 2013)

Here is an easily available source for Shelley’s great allegorical declaration of war on things as they are — along with some accompanying graphic history. One remarkable thing about Shelley’s poem, composed for “a little volume of popular songs wholly political,” is how it stays political: how it runs like a red thread through successive histories and movements, in ways that track and underscore the transformations in the repertoire of collective action. Its closing refrain is everywhere: “Rise, like lions after slumber, / In unvanquishable number, / Shake your chains to earth like dew / Which in sleep had fallen on you— / Ye are many—they are few— “. It begins as a response to the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, a mass gathering in London to demand reforms that was treated as a riot and bloodily set upon by the military. By the start of the twentieth century, the industrial age in full swing, it anchors the speechs of Pauline Newman as she organizes the International Ladies’ Garment Worker’s Union. The rough beast comes back in Phil Levine’s “They Feed They Lion,” which winds from the Second Great Migration to the auto workers of Detroit to the Great Rebellion of 1967. In 2010, Shelley’s poem is repatriated when students and others fighting fatal cuts to the social wage storm and occupy 30 Millbank, the Conservative Party headquarters in London. Shelley’s final stanza is cited repeatedly in the following days, returning in the long season that includes the movement of the squares, the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring—the new era of riots.

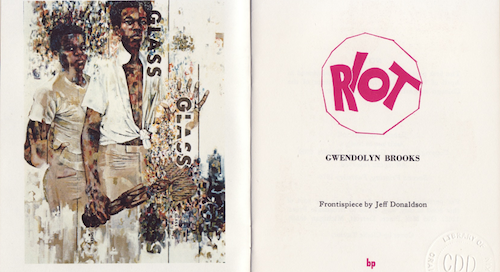

Gwendolyn Brooks, Riot (Broadside Press 1969)

This is a poem in three parts, a small books that contains worlds — written by the Pulitzer Prize winner after deciding she wanted to work with a black-run press, Dudley Randall’s incomparable Broadside. The opening title section, set in Chicago shortly after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, captures the encounter between John Cabot — conspicuous consumer, high-mannered gentleman, so white he is almost French — and the black underclass. “Because the Negroes were coming down the street,” pointedly not the black bourgeoisie whom he once encountered, they appear as blackness itself, “not detainable” and “not discreet.” It is a version of what is sometimes called these days “social death.” Unable to be granted humanity, they are figures for a massive immiseration, for a population pushed out of the economy that no longer has use for them, consigned to desperate life in the busted agora. In this regard the poem is not about the Chicago riots, exactly, but about how blackness coming down the street is, from the perspective of bourgeois whiteness, always a riot, or the moment after, or the moment before. “Don’t let It touch me! the blackness! Lord!” cries Cabot. It does not work out for him. The Lord — justice, necessity, the dialectic — has something else in mind.

Aimé Cesaire, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land (Wesleyan 2001)

This begins as every notebook should begin: “Beat it, I said to him, you cop, you lousy pig, beat it, I detest the flunkies of order and the cockchafers of hope. Beat it, evil grigri, you bedbug of a petty monk. Then I turned toward paradises lost for him and his kin….” Cesaire, Martiniquan theorist of négritude, friend of Senghor, teacher of Fanon, offers an anticolonial poetics which routes around the ideological oppositions of mid-century, offering a surrealism and a militancy against rather than in thrall to cosmopolitan modes. Unlike so many of his European peers, he broke with the Communist Party after the Soviet invasion of Hungary; in 2006 he refused to take a meeting with Nicolas Sarkozy because of his party’s support for a law requiring the teaching of colonialism’s benefits. We might take this in useful distinction to our poets content, even anxious to play the White House. Cesaire’s influence is everywhere. I can’t help but hear him, to choose only one example, in the Venezuelan poet Miguel James’ “Against the Police,” which begins (in Guillermo Parra’s translation), “My entire Oeuvre is against the police / If I write a Love poem it’s against the police.” Same.