What Slaves Decided

As part of a series of posts related to Black History Month, we present an excerpt from David Roediger's Seizing Freedom: Slave Emancipation and Liberty for All below.

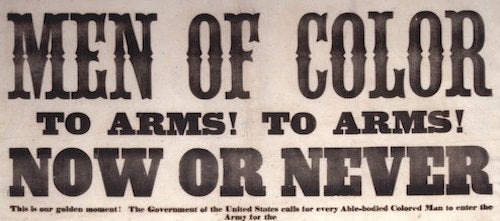

(from an 1863 broadside with text by Frederick Douglass)

Before major battles [of the Civil War] had even been fought, slaves left slavery — just three at first, fleeing into the Virginia camp of Union general Benjamin Butler. The general could see slaves being used to construct Rebel military fortifications across the lines dividing the two forces. A local Confederate commander owned the slaves who fled to the Union side. Butler, needing “able-bodied” men, could not bring himself to return the fugitives. Instead he sent the master a receipt for the slaves, nominating them as “contraband of war.” Frederick Douglass skewered the new language as morally opaque in the extreme, finding “contraband” to be “a name that will apply better to a pistol than a human being.” Lewis Lockwood, a missionary to refugees at Fortress Monroe, similarly denounced “contrabandism” as “government slavery.” Later approved by the secretary of war, the policy preserved the norms of slave property even as it opened new possibilities to resist bondage. Slaves were putatively to be returned or the disloyal owner compensated after an armistice. As did commanders in South Carolina, Butler’s subordinates recorded hours of labor by contrabands, with the convoluted rationale that masters were entitled to compensation for labor done to put down the rebellion they pursued. The North’s military necessities governed the process, which was avowedly not emancipatory, though Harriet Tubman’s assistance of General Butler illustrated the ways that African Americans struggled to use the contraband policy to expand freedom. Such policy did not apply everywhere or consistently protect those who had left slavery. The nurse Cornelia Hancock wrote to her sister on the day the Emancipation Proclamation took effect that she had recently encountered slave catchers operating in the northern Virginia camp in which she worked. They prowled about protected by a pass given by the general in charge. Douglass complained that even Butler was complicit in the slave-catching and in suppressing slave revolts. Tubman, equally skeptical of Lincoln’s slowgoing policies on emancipation, nonetheless went to the Sea Islands of South Carolina long before freedom was announced, possessed of a spiritual vision that the war would end slavery. She functioned as a nurse armed with a rifle, as a spy for Union forces, and as an organizer and strategist abetting mass escapes by slaves.

Had flight from slavery been rare, decisions to seize contraband might have been bureaucratic procedures following captures of slaves in Union victories. But slaves came by the thousands and, ultimately, the hundreds of thousands. Their uneven, protracted, and thoughtful motion—what W.E.B. Du Bois called “the general strike of the slaves”—placed slaves’ humanity and ability at history’s center. In May 1862, the South Carolina slave Robert Smalls commandeered a Confederate military transport named the Planter, delivering it, artillery, an important Rebel code book, and himself to the Union side. The skill of piloting, an ingenious disguise, and the fascinating defection of a slave presumed to be privileged and loyal fueled newspaper interest in the sensational story. Other dramas were witnessed within a smaller circle, but knowledge of them likewise diffused. The commander in Memphis in the early war began with hopes of keeping slavery from being an issue in a war for union, but the desires for labor, and for depriving the South of labor, soon transformed Memphis into a center of contrabands and then of Black troops.

The passing of the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act in July 1862 committed Lincoln to more or less the John Brown strategy of permanently liberating and arming slaves. But the long delay by Lincoln ensured that the public’s debates over whether emancipation was impossible and/or imperative matured. Freedom followed from the slave’s own heroism. Emancipation contributed to the national interest, to victory, and to making meaning of a protracted bloodbath that had come to seem more disabling than ennobling. The idiosyncratic but influential intellectual Orestes Brownson so appreciated the popular need for such meaning that he welcomed the Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure even though he insisted that he did not support emancipation.

Because of the motion of slaves — even in the face of highly public executions such as those following slave rebellions—the war had become something different. After the Second Confiscation Act, Karl Marx predicted, “So far we have witnessed the first act of the Civil War—the constitutional waging of war. The second act, the revolutionary waging of war is now at hand.” The Pennsylvania Republican Thaddeus Stevens urged just before the Emancipation Proclamation, “Free every slave — slay every traitor — burn every rebel mansion” in a conflict that he now saw as a “radical revolution” destined to “remodel our institutions.” That revolution would ultimately confiscate more property—the freed slaves had been just that—than any revolution in all history prior to the twentieth century. Douglass became a military recruiter of Black troops.

Nearly 200,000 African Americans joined the army or navy in the cause of the Union, 81 percent of whom were from the slaveholding states, many newly emancipated and armed. Douglass maintained that January 1, when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, was “incomparably greater” than July 4.

The impossibility of the slave’s motion from bondage to soldiering had seemed clear well into the war. As late as 1862, Lieutenant Charles Francis Adams, whose family represented the intersecting power of high culture and politics in the United States, registered how little sense the idea of Black soldiers still made to even some Yankee elites. He thought that with great and wasteful expense “a soldiery equal to the native Hindoo regiments” could be created in about five years. He added, “It won’t pay.” But, by July 1864, the same Adams had begun to admire Black troops whom he saw in action. He wrote, “They seem to have behaved just as well and as badly as the rest and to have suffered far more severely.” Others, seeing the brutal wage discrimination such troops faced and their courage both in confronting the Rebel enemy and in their direct attempts to emancipate slaves, had a still higher opinion of African-American soldiers. Among freedpeople, such soldiers enjoyed prestige reflecting their valor in battle and their roles in defending civil rights at home. The great historian of African-American troops, Dudley Taylor Cornish, wrote, “The Negro soldier proved that a slave could become a man.” Douglass’s own 1863 broadside “Men of Color to Arms” insisted that African-Americans would emancipate themselves.

The self-emancipatory acts of slaves during wartime powerfully affected masters’ psyches. Douglass’s pleas to end the Union’s policy of fighting “with one hand” and turn the war into a revolution of course emphasized the benefits of labor lost to the Confederacy and gained for the Union war effort, but more was at stake psychologically. As Douglass once phrased it, any “proclamation of emancipation” would “act on the masters” as well as the slaves. A sense of how brittle and apt to turn into hysteria the slave-owning class’s claims to mastery proved in the face of resistance suffused his autobiographical writings. During the war, such deep vulnerabilities characterized the reactions of masters and mistresses whose slaves ran away or stayed and disobeyed. The flight of trusted household slaves particularly drained confidence. When the washerwoman Dolly, whose owners categorized her as an “invalid” in plantation records, ran away, one of the leading families in Georgia lost not only their laundress but also their faith in the future and some of their confidence that they had ever mastered slaves. “The Negro women marched off,” Louisiana plantation mistress Kate Stone lamented, “in their mistresses’ dresses.” Stone was on the losing end of “the war within” plantation households, a contest shaking Confederate morale.

The magnificent drama of slaves’ movement toward a freedom by no means guaranteed by federal policy played out before and even after Lincoln’s proclamation. Many slaves suffered in Border States loyal to the Union but with significant pro-Confederate sympathies, especially among slaveholders. Well after accepting Butler’s contraband policy in Virginia, Lincoln still attempted to placate masters in the border regions and beyond, rejecting General John C. Frémont’s order emancipating Missouri slaves of disloyal masters, removing Frémont from his command, and floating ideas regarding exceedingly gradual, compensated emancipation. Defiant protests such as those directed at the War Department from border regions by General O.M. Mitchel in May 1862 helped shape debates over emancipation. Mitchel reported that continuing the policy of returning fugitives to masters had become impossible: “My River front [the Tennessee] is 120 miles long and if the Government disapprove of what I have done I must receive heavy re-enforcements or abandon my position. With the assistance of the Negroes in watching the River I feel myself sufficiently strong to defy the enemy.” But, well into 1863, the policy of returning slaves to “loyal” owners applied in the Border States. St. Louis used its city jail to hold recalcitrant slaves. A short distance away was Benton Barracks, where Blacks joined the Union army.

The processes that Butler began and that Frémont sought to broaden repeated themselves in many places, with those in the field staking out a variety of positions and Lincoln responding vigorously or not. The proposals and responses shifted as military fortunes ebbed and flowed and as laws changed. The current emphasis on Lincoln’s status as a moral exemplar and political genius makes for a flattened history, one that supposes that drama adheres to great men and too readily reads itself backward from its results. Thus, we get a Lincoln biding his time for the opportune moment to decisively strike blows at a slave system he detested. In the case of Frémont’s order, Lincoln is seen as shrewdly resisting an adventurist, politically driven general in the interest of the rule of law and of keeping Missouri and Kentucky slaveholders loyal to the Union. However, in 1862, when the “abolitionist general” David Hunter implemented a South Carolina emancipation and draft of freedmen after great preparation within the channels of government, Lincoln countermanded that order as well. Part of the context was a simultaneous debate over compensated emancipation in the Border States, which caused Lincoln to regard emancipationist appeals as “embarrassing.” Frémont’s successor was likewise removed for being too pro-emancipation. When Lincoln called the major general and railway engineer Grenville Dodge to Washington to discuss building the Transcontinental Railroad, Dodge feared he was to be the subject of disciplinary action for arming ex-slaves. The point here is not to deny that Lincoln faced enormous political problems and confronted longstanding habits of federal government respect for slave property. But it is necessary to insist that the drama of Lincoln slowly and gloriously changing be taken in the round, with slaves acting to teach commanders that their labor and loyalty could be decisive for the war effort. As the editors at the Freedmen and Southern Society Project remind us, “While Lincoln and his subordinates courted slaveholders, slaves demonstrated their readiness to risk all for freedom and to do whatever they could to aid their owner’s enemy.”