Staff Picks: Books of the Year 2015—Chosen by Verso

FICTION

The Story of the Lost Child by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein (Europa Editions, 2015); My Brilliant Friend (2012); The Story of a New Name (2013); Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014).

Several of us in the Verso team received our diagnosis this summer from a certified medical doctor who scrutinized our exhausted faces, distracted eyes and dramatic swings of emotion: “I’m sorry. You have come down with a severe case of Ferrante fever. The worst will pass but the hunger will never fade.” This fever of addiction stole sleep, stoked obsession and caused dangerous and foolish behaviour, such as crossing the road whilst reading—but it also brought new and old friends together in a happy haze of intoxication. Thus, here are some snippets from my brilliant friends that illustrate our year of reading Ferrante:

Elena Ferrante gave an interview to Vanity Fair about feminism and literature illuminating the experiences of Lila, Lenù, and us:“Are Elena Ferrante’s four Neapolitan novels even books? I began to doubt it when I talked about them with other people – mostly women. We returned to life too quickly as we spoke: who was your Lila, the childhood friend who effortlessly dazzled everyone? […] The usual distance between fiction and life collapses when you read Ferrante. She knows it too: writing the Neapolitan quartet, she has said, was like ‘having the chance to live my life over again’.

“It would be enough to have books in which we recognise the truth of women’s lives in all its darkness, but the Neapolitan quartet also has an almost deranging narrative pleasure, delivered in a style that’s more of an admission that the author cares too much about the truth to bother with style. The publication of the fourth and final volume is a terrible moment.”—Joanna Biggs

“I grew up with the idea that if I didn’t let myself be absorbed as much as possible into the world of eminently capable men, if I did not learn from their cultural excellence, if I did not pass brilliantly all the exams that world required of me, it would have been tantamount to not existing at all. Then I read books that exalted the female difference and my thinking was turned upside down. I realized that I had to do exactly the opposite: I had to start with myself and with my relationships with other women—this is another essential formula—if I really wanted to give myself a shape. Today I read everything that emerges out of so-called postfeminist thought. It helps me look critically at the world, at us, our bodies, our subjectivity. But it also fires my imagination, it pushes me to reflect on the use of literature. I’ll name some women to whom I owe a great deal: Firestone, Lonzi, Irigaray, Muraro, Caverero, Gagliasso, Haraway, Butler, Braidotti.

“I hold that male colonization of our imaginations—a calamity while ever we were unable to give shape to our difference—is, today, a strength. We know everything about the male symbol system; they, for the most part, know nothing about ours, above all about how it has been restructured by the blows the world has dealt us. What’s more, they are not even curious, indeed they recognize us only from within their system.”

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2015)

Claire-Louise Bennett’s debut collection of short stories explores the territory where a woman’s solitude meets the external in a startingly distinctive, original voice. The physical world is turned inside out to reveal the unfamiliar in fragmentary, modernist prose; in Chris Kraus’ words, “wielding a wry but implacable logic, Claire-Louse Bennett dives under the surface of “ordinary” experiences and things to reveal their supreme and giddy illogic.” Witty and beautiful, Pond is published in a handsome edition by ambitious new publisher Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera, translated by Lisa Dillman (And Other Stories, 2015)

And Other Stories have brought some brilliant translated writing to English-speaking readers this year, and Signs Preceding the End of the World is no exception. This book is a beautifully written tale of a young Mexican migrant woman journeying to the US. Lyrical, poetic, haunting: the writing is exceptional, somehow managing to be simple and complex at the same time.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith, (Portobello Books, 2015)

This small and tightly wound novel about housewife Yeonge-Hye’s dramatically escalating relationship with nature begins innocently, with her vow not to eat meat. What proceeds from this minor act of non-conformity is a vivid and startling metamorphosis, of which the experience to read is both deeply unsettling and profoundly compelling.

Yeonge-Hye’s journey could have easily been presented as a flight to a virtuous ‘natural’ order, away from a corrupt and contrived modern world that exploits and oppresses her. However, rather than simply absconding to the woods, The Vegetarian is far more interesting, burrowing down into the fissures of society and jolting the structures of what we too-often accept to be the most unshakably ‘natural’—the body, gender, and the family. Han Kang reminds us that when these sacred cows are under threat, violence by the state and civil society is never far away. A heartbreakingly beautiful work.

Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi (Zed Books, 2015)

Reissued by Zed Books this year as part of a gorgeous set of three new editions, this classic feminist work is still as powerful, relevant, and compelling as ever. Described as a “blood-curdling indictment of patriarchal society” by the Guardian, is it easy to see within just a couple of pages why Nawal El Saadawi is one of the most influential feminist thinkers in the Arab world. What’s harder to understand is why she has been left out of the western feminist literary canon for so long (although we all know why). Woman at Point Zero fictionalises a true account of a woman in a Cairo prison awaiting execution, and will leave you eager to read more by the author.

Another Country by James Baldwin (Penguin, 1962; 2001)

A novel of tormented love, intertwined with the subjectivities of race, gender, and sexuality in the desolation of 50s Harlem. Baldwin at his best, and as relevant today as it was when it first came out.

The Bees by Laline Paull (Ecco, 2014)

The Handmaid’s Tale but with bees. Quirky, dystopic eco-feminist sci fi — worker bees resisting a matriarchal caste system, a bourgeois class of drones feasting on the hive’s riches and contributing nothing, and a benumbing, opiate-of-the-masses priestess religion in service to the queen bee. Campy, sure, but Marxism dressed up lush and pretty and exploring ecological devastation.

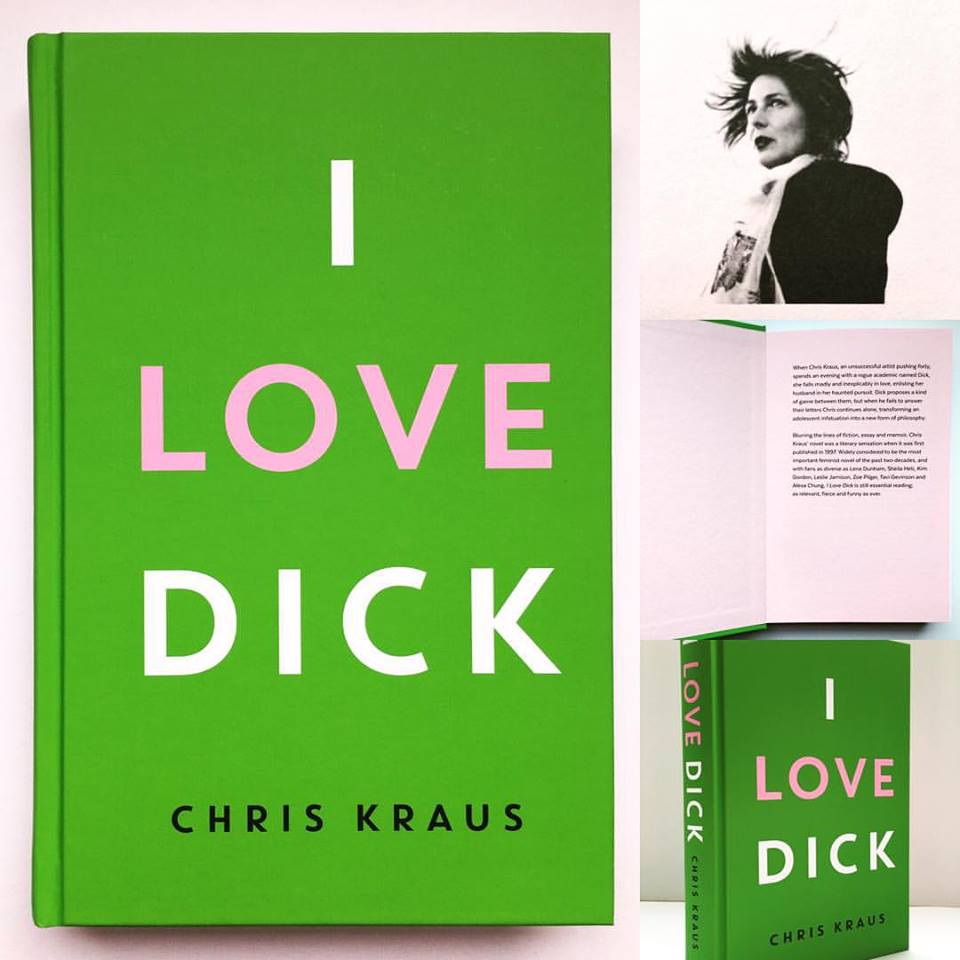

I Love Dick by Chris Kraus (Tuskar Rock, 2015)

First published in 1997, Kraus’ feminist experiment with genre has become a feminist cult classic and has now been republished in a gorgeous new hardback edition by Tuskar Rock, an imprint of the UK-based Serpent’s Tail. Blending autofiction with theory, criticism, memoir and love letters, the heroine of the novel, also called Chris Kraus, charts the terrain of women’s desire, art and consciousness.

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein (Europa, 2005)

Visceral, dizzying, terrifying—this slim book does more in 192 pages than most in double that. The opening paragraph says it all:

One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me. He did it while we were clearing the table; the children were quarrelling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator. He told me that he was confused, that he was having terrible moments of weariness, of dissatisfaction, perhaps of cowardice. He talked for a long time about our fifteen years of marriage, about the children, and admitted that he had nothing to reproach us with, neither them nor me. He was composed, as always. … Then he assumed the blame for everything that was happening and closed the front door carefully behind him, leaving me turned to stone beside the sink.

Chelsea Girls: A Novel by Eileen Myles (Ecco, 2015)

I finally got round to reading this cult, coming-of-age novel and was not disappointed. Chelsea Girls is a book of prose that reads like memoir, with exhilaratingprose, even at its most bleak. “A modern chronicle of how a young female writer shrugged off the chains of a rigid cultural identity meant to define her.”

Carol by Patricia Highsmith (Bloomsbury, 2010)

Patricia Highsmith was in love many times and with many women – “more times than rats have orgasms”, to quote her directly. First published as The Price of Salt in 1952, and written under a pseudonym (for fear of a backlash for writing so openly about a lesbian relationship), Carol is currently gracing our screens in a new film with Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. But don’t let that put you off reading the book. The compelling, haunting and exhilarating narrative will have you racing through it in one sitting.

Early Levy: Beautiful Mutants/Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy (Penguin, 2014)

Amazing collection of two short early works from Deborah Levy. Rough and unpolished in the best way, with lines that will leave you spinning for days.

The Weight of Things by Marianne Fritz, translated by Adrian Nathan West (Dorothy Project, 2015)

The first of the late Marianne Fritz’s works to be translated into English. This odd gem swerves from uneasy pantomime comedy to sheer domestic horror. Fritz has a clammy handle on all that makes humans miserable: roll up for the horrors of jealousy, war, confinement, mental illness, regret and unhappy motherhood.

The Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers (Mariner, 2005)

Uncouth romance and lonely longing shine out from McCullers’s “dreary” small Southern town, resulting in a strange and brilliant novella.

The People’s Act of Love by James Meek (Canongate, 2013)

Ignore the lazy reviews comparing this to classic Russian fiction. Meek’s novel is set in Russia and has a period setting, but the similarities pretty much end there. This is a fast-paced contemporary novel, dense with themes and characters, and fascinated with the graphic intricacies to be found at the extremes of human experience: imagine David Mitchell if he got his weirdness from history instead of sci-fi and wasn’t afraid of the mid-period in a story. Herein you will find the lost Czech army of World War I, a Siberian commune of religious castrates, and anthropophagi wandering the frozen steppe—all in a past recreated with such care and solidity it rings like a bell.

The Spectator Bird, All the Little Live Things, by Wallace Stegner (Penguin, 2013).

My shameful pursuit of stately fiction in which miserable bourgeois Americans grow old and remember things that happened years ago (while taking the occasional long walk) continues… Despite that categorisation this is a fine pair of novels. Stegner wrote charmingly about death.

MEMOIR AND BIOGRAPHY

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates (Spiegel & Grau, 2015)

A letter written by the Atlantic contributing editor to his son becomes the clearest statement of the emergency faced by black bodies in America today.

Toni Morrison’s blurb speaks louder than I could: 'I've been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin died. Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates. The language of Between the World and Me, like Coates' journey, is visceral, eloquent and beautifully redemptive. And its examination of the hazards and hopes of black male life is as profound as it is revelatory. This is required reading.'

King Kong Theory by Virginie Despentes (Serpent’s Tail, 2009)

Charting Despentes' journey through poverty, rape, sex work, pornography and then fame as the director of Baise-Moi, it’s a furious, polemic-come-memoir as provocative and contentious as it is illuminating. Feminist fire for the soul.

Hunger Makes Me A Modern Girl by Carrie Brownstein (Virago, 2015)

Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl is engaging and illuminating, deftly telling the story of how the Sleater-Kinney guitarist found her way to music. Performance was her means of escape from a turbulent family life into a world where music—and now writing—was a means of embodiment and expression. Brownstein narrates the rise of Sleater-Kinney and their musical milieu, but the book is more in dialogue with first-person writing by women than music memoirs. In interview with Lidija Haas, Brownstein says: "There is a lot in my book about personhood and persona and about a sense of belonging, and whether you sort of deserve to be at the forefront. Always calling into question the right to really be at the center of your own narrative. Having to really carve that space out, and then sort of resenting the fact that you had to carve that space out. And so it is a book that is in dialogue with itself."

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson (Graywolf Press, 2015)

Maggie Nelson wraps this long, roving personal essay with ribbons of poetry and theory in such a fashion as to remind me of why I fell in love with both as a much younger person.

“If The Argonauts can be said to have a primary concern, this is it: how to resist a concept of queerness that shoehorns complex lives into a neat dichotomy of normative versus not, and how to resist the unhelpful demonization of motherhood, domesticity , and the other supposedly reactionary forms love can take.” N+1

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert Caro (Bodley Head, 2015)

Finally released in the UK, this extraordinary biography of Robert Moses, the master planner who utterly reshaped New York, is an exemplary exploration of the corruption of idealism, and the dangers of power. Possibly one of the best biographies of the last few decades.

Drawing Blood by Molly Crabapple (HarperCollins, 2015)

The stunning and long-awaited autobiography from the artist and journalist Molly Crabapple. From the glowing New York Times review: “Crabapple draws like a madwoman. Drawings spool out of her. When she was in pain, she 'unrolled a three-foot piece of paper.' When inspired, she drew 'in ecstasy,' propping the drawing up so she 'could stare at it as I fell asleep.' In a jail cell after a protest, penless, she scratched 'a self-portrait into my Styrofoam cup.' No matter what happens, she draws anyway. She loads the paper until it’s cramped and bursting, until it 'swarmed like an ant colony.' 'I wanted to pack each page so full of life that it resembled a Bosch fantasia or a Persian miniature or Where’s Waldo,' and it does.”

JOURNALS

LIES II: A Journal of Materialist Feminism (2015)

Three years after setting fire to our minds and hearts with the first issue, LIES is back with a volume of intersectional, materialist feminist discussion around gender, race and class, spanning sex work, colonial gender violence, racism, rape culture, reproductive labour, poetry, stories and artwork. A central essay, ‘Many Lines, Many Bonds’, written by several individuals in the LIES collective, an autonomous feminist project composed of only non-cis-men, states:

We’ve sought to make our feminism antagonistic toward the racism and transphobia of historically hegemonic feminisms, as well as the racism and transphobia in our current political milieus and in society at large […] As a collective of heterogenous composition, we have tried to name and confront the tensions we’ve encountered around our differences in identity, power, and class, which are together fundamental to the reproduction of capitalist social relations – and so we seek to build a praxis that encompasses all of these parts of the whole. To engage in such a project is to continuously struggle with each other, and with ourselves.

ENDNOTES 4: Unity in Separation (2015)

The Endnotes collective go from strength to strength with their latest issue, extending their rigorous analysis of surplus populations and a long essay 'A History of Separation', developing their examination of Theorie Communiste's history of the workers' movement of the twentieth century which is sure to become a touchstone for discussions of political and economic periodisation on the left for years to come. Their brilliant and nuanced approach to the #BlackLivesMatter movement, much like the essay on the London Riots in #3, is another highlight.

POLITICS AND THEORY

All Day Long: A Portrait of Britain at Work by Joanna Biggs (Serpent’s Tail, 2015)

A fascinating book detailing the (often very strange) world of employment in Britain today. Unlike many books on this subject, Biggs puts workers (rather than endless theory) at the forefront of her writing: she travels around the UK to interview a sex worker, call centre worker, former Pret A Manger employee, an unemployed man on compulsory government work placements, and lots more. Biggs is insightful and writes beautifully: underneath it all simmers razor-sharp social & political awareness, and a brilliantly executed critique of emotional labour, zero hours, unemployment, and everything in between.

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde (Ten Speed Press, 2014)

Sister Outsider is an absolutely essential collection of fifteen essays and speeches from 1976 to 1984. Audre Lorde, both the ‘sister’ and ‘outsider’ of the title, explores the complexities of intersectional identity, drawing from her personal experiences with oppression, including sexism, heterosexism, racism, homophobia, classism, and ageism. In response to the tendency of mainstream feminism to deny difference between women, thus replicating hierarchies where the most privileged dominate, Lorde argues that difference—and the anger of the oppressed—can be productive for liberation. Sister Outsider presents groundbreaking work that is strikingly relevant today, and is all the more valuable for challenging its readers to question and scrutinize their own complicity in structures of oppression and the privilege that blinds them.

PostCapitalism: A Guide to Our Future by Paul Mason (Penguin, 2015)

Developing his argument in Why It's Still Kicking Off Everywhere, and a companion to Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams Inventing the Future, Paul Mason's new book first examines the crises of capitalism from the 19th to the 21st century, while providing an excellent (and surprisingly accessible) guide to the debates on their understanding in Marxist theory, and then goes on to speculate on a future of zero marginal cost, automation, and a global public sphere. Very provocative.

Campus Sex, Campus Security by Jennifer Doyle (Semiotexte, 2015)

“The management of sexuality has been sewn into the campus. Sex has its own administrative unit. It is a bureaucratic progression.” – Doyle, Campus Sex, Campus Security

On campus, the criminal and civil converge, usually in the form of a hearing that mimics the rituals of a military court, with its secret committees and secret reports, and its sanctions and appeals. In this short book, Doyle looks at the dark world of campus sexual assault, rape discourse, litigation, and more; in the wider context of campus (over) policing, hyper-corporatization, and bizarre crisis management.

Transit States: Labour, Migration, and Ctizenship, and Labour in the Gulf ed. by Omar AlShehabi, Adam Hanieh and Abdulhadi Khalaf (Pluto Press, 2014)

In the wake of increasing turmoil in the Middle East, this brilliant and accessible collection of essays explores the pivotal role in the global economy played by the six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Bahrain. Bringing together experts on the Gulf, Transit States tackles this regional bloc’s reliance on temporary, migrant workers with no citizenship rights and the construction of class, gender, city and state. Combining rich historical analysis with a timely assessment of contemporary politics, this book is an indispensable tool for approaching the precarious working conditions faced by global migrants today.

How the West Came to Rule: The Geopolitical Origins of Capitalism by Alex Anievas and Kerem Nisancioglu (Pluto Press, 2015)

Excellent survey of non-Eurocentric factors in the development of Capitalism. Taking in everything from the Ottoman-Hapsburg rivalry, Mongolian nomads of the steppe and the Eurasian trading routes and the Atlantic slave trade, this is a brilliant and very readable study. Perhaps suffers slightly from having such a vast scope, but still a must-read.

The Portable Hannah Arendt by Hannah Arendt (Penguin, 2003)

Probably the book that I have spent the most time this year getting to grips with. A worthy introduction to an important thinker.

Lacanian Psychotherapy by Michael Miller (Routledge 2011)

A brilliant and engaging entry-point to Lacan, particularly for Lacan-sceptics. It carries a blurb from Bruce Fink: “lucid, beautifully written discussion of the use of Lacan's work in clinical practice. Targeting topics of concern to the widest range of practitioners – including insight, opening up of 'potential space,' transference, countertransference, gender, and power dynamics – he provides word-for-word transcripts of interactions with his clients that beautifully illustrate a Lacanian approach to listening and interpreting that can be applied in a great many therapeutic settings, using theory to illuminate – but never overshadow – the case material. The level of detail provided in his case studies is unrivaled. A fabulous achievement!”

The Brenner Debate ed. by TH Ashton and Charles HE Philpin (CUP, 1985)

This selection of essays, originally published in Past and Present, details the reaction from a range of historians to Robert Brenner’s provocative essay on late medieval agrarian class structure and the transition to capitalism. Perhaps the ur-text of Political Marxism, this collection, even 30 years after its original publication, is stimulating and rewarding.

Parliamentary Socialism: A Study in the Politics of Labour by Ralph Miliband (Merlin, 1961)

While not the most sophisticated book theoretically, Parliamentary Socialism is still one of the best critiques of the ideology of 'labourism' around. I picked the book up during Jeremy Corbyn's election campaign, and was stunned by the frequency with which I read whole passages that could have been written today – literally word-for-word. It helped to crystallise two things in my mind very clearly: first, the extent to which Corbyn's tendency to embrace extra-parliamentary political agency breaks not only with 'New Labour', but with the venerated 'Old'; and secondly, the need for autonomous radical organisation not bound to his own fate within the party machinery.

POETRY

Jane: A Murder by Maggie Nelson (Soft Skull Press, 2005)

Jane traces the life of Maggie Nelson’s aunt Jane and the emptiness left by her murder in 1969 through ‘docu-poetry’: a collage of poetry, prose, and documentary sources, including newspapers, related "true crime" books, and fragments from Jane’s own diaries. At once a haunting investigation into the unknowability of another’s life and death, Jane is also a powerful treatment of gendered violence and a moving elegy.

It’s No Good by Kirill Medvedev, translated by Keith Gessen (Fitzcarraldo, 2015)

It’s No Good is the first book in English by Russian poet and activist Kirill Medvedev and it’s actually very good. Collecting poetry and polemics, Medvedev’s sharp irreverence targets the post-Soviet liberal intelligentsia and observes life in Putin-era Russia in wry free verse. This book is published by Fitzcarraldo without the permission of the author, who gave up copyright on his work in 2004 as a “gesture of yearning for the international progressive intellectual, artistic and political movement that seeks a way out of neoliberal capitalism.” Experimenting with the production and dissemination of culture in this way, Medvedev since found that “publishers who want to put out my book are forced to take on a certain responsibility that forces them out of the realm of professional publishing and into the realm of political and even ethical choices.” (Guardian)

Letters to the Firmament by Sean Bonney

The new collection from Sean Bonney is a thrilling, honest and angry series of poems. The rage is always precise, the connections to 17th century mysticism stir a connection that goes beyond the glibly psychogeographic, and the melancholy is never comfortable. Highlights are the eerily prescient Letters on Riots and Doubt written on the eve of the 2011 riots, and the tumbling The Commons.

The Penguin Book of Renaissance Verse: 1509-1659 (Penguin, 1992)

Brilliant collection of early modern English verse compiling everything from Marvell, Shakespeare and Milton to a couple of (pretty terrible) poems from Elizabeth I.

MUSIC

Turn the Beat Around by Peter Shapiro (Faber, 2009)

A cultural and political history of disco, from its antecedents in the Swing Kids scene in 1930s Germany to the last few sad sequinned sputters in the ’80s. Shapiro reads Fire Island fun and frolics through Guattari, and thoughtfully includes an exhaustive discography <3

CRITICISM, ESSAYS, CLASSICS

The Age of the Crisis of Man: Thought and Fiction in American 1933-1973 by Mark Greif (Princeton, 2015)

A brilliant, unexpected exploration of mid-century American thought. Despite the States being at their most confident as a superpower, the nation's intellectual landscape was riven with doubt over the the disappointments of the 'age of man'. Shimmering in insights, Greif makes us think again about the victories of the 20th century.

Paideia: The Ideals of Greek culture (3 volumes) by Werner Jaeger (OUP, 1985)

Werner Jaeger was possibly the greatest German philologist of the 20th century. He managed to combine excellence in classical philology with militant anti-Bazism and a strong sense of the necessity to innovate the culture of his own time. His magnum opus in three volumes, Paideia, can be considered as the peculiar manifesto of what he called ‘a third humanism’. Aside from the agenda behind the text, this is an astonishingly comprehensive and erudite exploration of the development of ancient Greek culture. Highly recommended.

Wordsworth: A Life by Juliet Barker (Harper Perennial, 2006)

Wordsworth has gone down in history as another writer to pursue that tedious trajectory from radical youth to reactionary old age. Even Keats, a big fan, bewailed the moment when his hero demeaned himself by taking a government post. Poets aren’t meant to have such sordid things as jobs, are they? So what if they do have an enormous family to feed and a healthy suspicion of patronage. In truth, Wordsworth was a complex mix of opinions and stances, capable of rallying support for Tory candidates in the North while applauding the People’s Charter. His changing attitude to the French Revolution is an insight into radical British thought of the time. But despite later revisions, The Prelude remains a paean to a revolutionary time when ‘to be young was very heaven’. This is great social history, detailing that delightful romantic period when anyone could drop stone dead anywhere at the least provocation.