To be real: On trans aesthetics and authenticity

Responding to Juliet Jacques' Trans, journalist Shon Faye examines the play between notions of authenticity and gender in fashion, social media and IRL.

“We may take advantage of this pause in the narrative to make certain statements. Orlando had become a woman — there is no denying it. But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been. The change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatever to alter their identity. Their faces remained, as their portraits prove, practically the same.”

“The change seemed to have been accomplished painlessly and completely and in such a way that Orlando herself showed no surprise at it. Many people, taking this into account, and holding that such a change of sex is against nature, have been at great pains to prove (1) that Orlando had always been a woman, (2) that Orlando is at this moment a man. Let biologists and psychologists determine. It is enough for us to state the simple fact; Orlando was a man till the age of thirty; when he became a woman and has remained so ever since.” — Virginia Woolf, Orlando (1928)

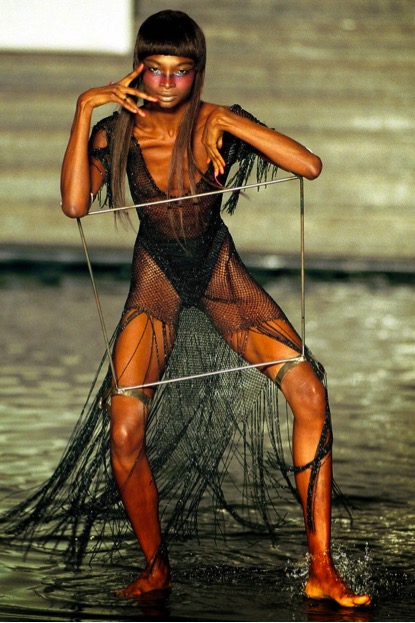

Reviewing the early collections of Alexander McQueen, as I did recently, it’s not hard to imagine the general outrage they would have caused had they been contemporaneous with social media. In his 1995 show ‘Highland Rape’, the models walked the catwalk battered and bloodied, the tailored tartans and frequently ripped garments hanging near their breasts. In his 1997 show ‘La Poupee’ (‘The Doll’), black model Debra Shaw walked the catwalk in a shackle. In 1999, Shalom Harlow struggled to maintain her poise in heels, wearing a white gown whilst robotic and sinister mechanised spray guns surrounded her, hitting her with pelts of colour.

- Debra Shaw, Alexander McQueen's ‘La Poupee’, 1997

What McQueen’s aesthetics show again and again is a duality to both fashion and femininity. Within the structure and finesse of his construction, the women who wore his garments could revel in the power lent to them by his silhouettes. However, McQueen understood that violence was never far behind either fashion or femininity. Indeed, he understood that fashion is a form of violence.

This idea comes as no surprise to trans people. Reading Juliet Jacques’ Trans: A Memoir, it struck me that in narrating much of her life in Manchester and Brighton as a student, Jacques conscientiously describes not only what she experienced and where, but also, almost always, she recalls what she wore, sometimes in scenes taking place well over ten years ago. Indeed, before reaching an awareness of the word ‘transgender’ as “a term that opened space between male and female,” Jacques frequently attempts to articulate her identity though clothes. Previously, she tried on the terms “cross-dresser” or “transvestite,” before, perhaps, recognising these terms, referring to exteriority only, did not fit.

- Tom and Julia. Photograph: Sophia Spring for the 'Transgender Children', Guardian, 12 September 2015

That’s not to say the issue of attire is not important. In the British media there is increasing interest in the issue of children who express that they are transgender or gender-questioning: the Guardian reports that referrals for transgender children rose from 97 new cases in 2009 to 697 in 2014. And, lacking agency, these transgendered children are at risk of depression, self-harm and other harmful effects of gender dysphoria caused by the mundane gendered assumptions of hair length, school uniforms and social interaction. Further, statistics of violence against trans people—the number of transgender people murdered in the U.S. this year is at a historic high—offer a sobering picture of what can happen to a trans person who does not ‘pass’. A 2013 report from the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found that anti-LGBT homicides are composed of 72 percent women, and 67 percent of these victims are trans women. A 2014 AVP analysis found that transgender survivors were 3.7 times more likely to experience police violence compared to non-transgender survivors—and further, transgender people of colour are 6 times more likely to experience physical violence from the police compared to white cisgender survivors. In Britain, police records from 2014 suggest transphobic hate crime in London alone may have risen by 44 per cent in 2014, most going unreported or investigated.

Yet away from the daily school run and the streets, the worlds of celebrity and fashion are repurposing this question of gender aesthetics within its enclaves of privilege and flamboyance. Beautiful trans fashion models like Hari Nef or Andreja Pejic (the latter’s beauty so impressive, it seems, that she won both the Homecoming King and Queen titles at her high school) are being widely acclaimed and exposed. The actor Ruby Rose, star of Netflix drama Orange Is The New Black, discussed her ‘gender fluidity’ earlier this year – leading to exclamations from heterosexual women and gay men that they would go gay/straight “for” her, respectively. London’s Selfridges store is now home to the high-end brand Agender, which claims to celebrate “fashion without boundaries” and to provide a “glimpse” into a world without gendered fashion.

‘Androgyny’ has never been more fashionable. A quick Google image search will show the general parameters of the fashion industry’s expressions of the word: a sea of monochrome faces. Young, boyishly feminine faces and bodies, all of them white—a reminder that while gender ambiguity may be fashionable, other hierarchies remain in place. That trans aesthetics (for want of a better term) and fashion are natural bedfellows is not surprising: both at once subvert and assert notions of ‘authenticity’.

‘Authenticity’ is a bind for transgender people. We expose the lack of rigidity in gender, but in a society so fixed on gender ‘authenticity’, we have to re-assert new forms of realness. Gender 'authenticity' is very much in the eye of the beholder, yet we must negotiate this gaze to live our lives and be taken seriously. In the case of nonbinary trans identities, this can be particularly difficult. I do not see myself as male or female but at times must settle for inhabiting parts of either or both identities to create my own. Nonbinary people may have no visible process of single transition, yet I’m constantly in transition. I am interminably transitioning – away from cisgender manhood but not “towards” anything, which is a difficult notion to exteriorise or authenticate in a binary gendered world.

‘Authenticity’ presumes a kind of stable truth – in the world of art history, for example, authenticity – that is, verifiable origins and histories – is both a form of praise but also a practical means to assign value to the art object as commodity by art historians and dealers. A work can lose all its monetary value overnight if its authenticity is discredited. Similarly, high-end fashion has embraced some trans models, but this has to be ratified by a multi billion dollar industry and magisterium that sets the terms for its acceptance of trans figures. An interview with Vogue reveals that Andreja Pejic faced warnings and criticism from industry insiders after deciding to undergo sex reassignment surgery, because “there are loads of pretty girls out there.” One agent even said, “It’s better to be androgynous than a tranny.” In other words, Pejic would cease to be profitable if she stopped being authentically inauthentic. But trans people and their bodies must not be commodified, as if we are clothes. “Trans aesthetics” in fashion should not be a passing trend, because the experience of gender fluidity is not a passing trend. As Ray Filar rightly notes: “Gender identity has no fixed end point: it is a lifetime of changing feelings, experiences and attitudes. If gender is a set of relationships – to ourselves, to others, to the boxes others put us in – then no adults are the same gender, really, as when they were born.” There can be no verification, no fixing of origins in the erratic vibrations of gender throughout a human life. Fashion riffs on and profits from the unverifiable, the ambiguous authenticity of androgynous trans models. But what value does that give to a trans life?

- Marsha 'Pay It No Mind' Johnson

In Trans, Jacques describes how an older trans woman she had contacted via the Internet queries her when Jacques calls herself a “drag queen”. In a telephone conversation, the woman asks Jacques if she wants to be on stage and perform – when she says no, she’s told she is not, then, a drag queen. Indeed, the 1992 documentary Paris is Burning and the histories of countless trans people will attest: the distinction between drag and trans aesthetics is complicated. Marsha P. Johnson, a central figure in the Stonewall riots, frequently called herself a “queen”. Many histories now retrospectively call her a trans woman. Drag enjoys one clear advantage over the aesthetics of gender as transgender people must negotiate them: it is all playfulness and subversion, upturning notions of authenticity. A drag queen may be praised for the success of her artifice, the guile of her deception. The trans aesthetic (from the perspective of the trans person themselves) is not about success in deception but truth. Trans people, especially those of us who are nonbinary or do not ‘pass’ within binary models, constantly risk violence for a perceived lack of authenticity. In our offices and at bus stops. Like an art work whose value plummets, our aesthetics can be perceived as a deception that means we can be sexually harassed or threatened with violence.

This harsh price of being visibly trans is at times hidden in the politics of ‘visibility’ and the celebration of trans aesthetics in the media. Caitlyn Jenner, whose entire family revels in another genre that toys with authenticity, reality TV, is the most obvious face of this. Her ’reveal’ moment, on the cover of Vanity Fair, with all the high-budget gloss, the bold invitation to call her by her new name and choreographed release on social media was greeted with acclaim, much of it focusing on Jenner’s beauty as a woman – her success in transition, as it were. It reminded me less of the confusion and struggles in the process of becoming an authentic self that Jacques’ memoir narrates, and more of the instantaneous, chrysalis-emergence moment in Sally Potter’s 1992 film Orlando, in which Virginia Woolf’s titular, aristocratic hero/heroine (played by the serenely androgynous Tilda Swinton) awakens to find herself indisputably, beautifully transformed from man to woman.

This kind of narrative obscures the material demands of transition and the many other difficulties as most trans people experience it (money, mental health, violence). But the greatest political danger is the way trans people are utilised to reassert traditional gendered aesthetics, pandering to the ‘Before’ and ‘After’ of binary gender. Just as conservative and liberal institutions have incentivised some privileged lesbians and gays into assimilationist politics with marriage and access to the army, so too there is a tacit offer of assimilationist aesthetics here for those trans people who can or wish to sign up to the new narratives and aesthetics of gender being written for them, mostly by a cisgender media and society.

- & Other Stories

Nevertheless, in the wake of Jenner’s announcement, young trans people were using apps to make their own Vanity Fair covers to share on their blogs and social media accounts. This is a very ‘millennial’ form of resistance: the Instagram filter is beloved of many young trans people (one need only search #trans). This is perhaps because selfies satisfy two aspects of our experience: the desire for control over our aesthetics, to own our notions of authenticity—and also our awareness that we cannot ever stop these being consumed, assessed and validated by others. In fashion and art, I believe these can be achieved too – but only when trans people themselves are at the forefront and at the helm. The & Other Stories campaign, which featured not only trans models but a trans stylist, photographer and make-up artist is a leading example of how an all-trans fashion team can challenge the traditional cis gaze in fashion. Elsewhere, the South Asian trans/nonbinary activist-art partnership, DarkMatter, tours the world and the internet creating and articulating a perspective entirely shaped by trans people of colour.

- DarkMatter

Challenging the violence of the cis gaze is a task for trans people ourselves, and it is important for cis people who want to support trans people to realise this. In Trans, Jacques recalls her friend Dave – no doubt wanting to protect her “in a rough bit of town” – messages telling her not to “dress up” on a night out. He later apologises, recognising this was panders to victim-blaming ideas of ‘bringing it on yourself’. Indeed, in my own life some of the most difficult parts of the ‘cis gaze’ is not hostile people seeing me, but family members and friends seeing me being seen. Becoming uncomfortable or fearful, they end up transferring that fear to me (“people keep staring at you Seán”). Suddenly, they – my supporters- have inadvertently become the conduits of other people’s violence.

This threat of violence is not unique to trans people – it also continues to happen to cis women and to cis people of colour in a white patriarchy that uses shame to control people and how they are seen. In every case, this is only resisted by people taking back power and autonomy to control how they are seen – gradually needing less external validation from society. It may sound needy or vain, but if gender identity is established partly in our relation to others, in the meantime, we still need others to validate (even praise) our disruption of this. Like Jacques, we are not taking to a stage to perform but there’s the acute awareness we’re being made to perform, regardless. Like McQueen’s models we’re being forced down a catwalk. I hope for a world where I have the bravery to defiantly step off it. But, while I’m here, have a look at the structure and the tailoring.

Shon Faye (@ShonFaye) is a writer and journalist.