'Is it a man or a woman? Transitioning and the cis gaze' by Ray Filar

'Pre-op'. 'Post-op'. 'No-op'. Not until recently did anybody question why trans people should be defined exclusively by whether or not they'd had genital surgery. Though gender variance has existed in most cultures throughout time, trans people today – particularly women – are still forced to situate themselves in relation to the idea of the medicalised 'sex change'. Have you had the op? Are you planning to? Are you taking testosterone? How far will you go?

Supposed 'transgender tipping point' aside, we have a set of expectations to live up to. To be trans you must 'come out' as trans. You must undergo a lengthy process of ‘transitioning’. You must make a 'trans statement', appearing as trans in public, before preferably disappearing into your 'new' gender: man or woman. Visibility is key here: the cis gaze demands you reveal yourself, offer yourself up for evaluation, even as it threatens you with violence for doing so.

As Juliet Jacques shows in her new memoir, Trans, the history of the 'sex change' is not just one of cis power over trans lives, but of cis prurience, reducing a gamut of differing trans experiences and embodiments to a set of sexualised assessments: does she pass? Is that top surgery or just a chest binder? Is it a man or a woman? For trans men, 'have you had the op?' can be mixed with total ignorance over what 'the op' might actually entail. Our castration anxiety is society-wide.

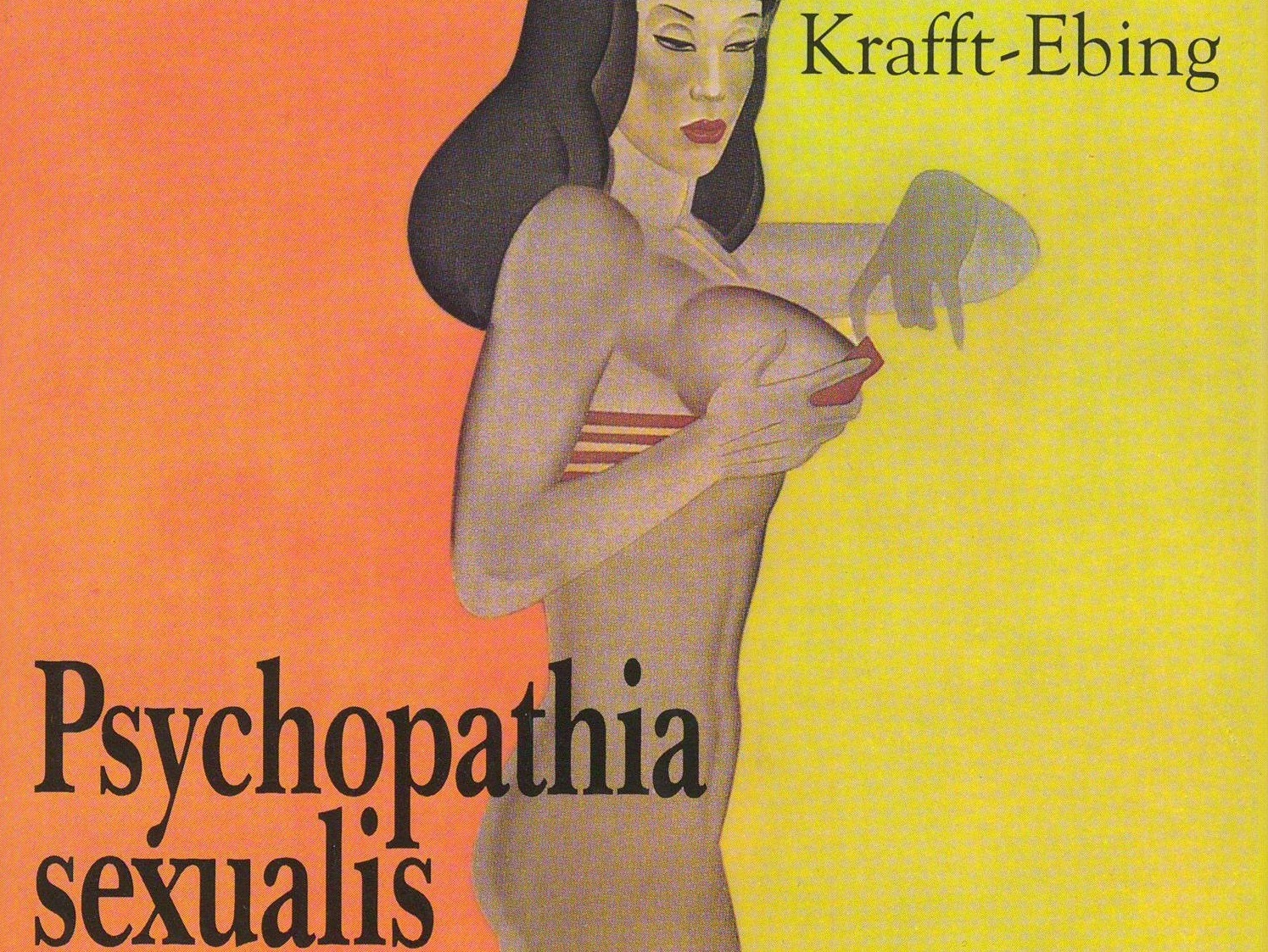

Jacques traces European 'trans' identities back from before the late 19thcentury emergence of sexology – mentioning Dionysian cross-dressing and its biblical prohibition in Deuteronomy 22:5 (“an abomination unto the Lord”) – but today, any trans person who desires to live openly has to contend against a set of arbitrary gender dogmas barely changed since the early sexologists. From the 1880s onwards, male scientists assumed rights over other peoples' experience of gender – inventing terms, categories, and treatments for those they termed 'sexually deviant'. Richard von Krafft-Ebing, considered the first sexologist, believed that living as another gender was a delusion, and that transsexual people were psychotic. This so-called science was enacted as social control – the legacy of which we are still contending with.

Trans lives are structured by dehumanising constraints invented by cis people. These regulate how you are and aren't allowed to be trans, through lawmaking and medical institutions. Just to live while trans requires supplication to stigmatising state processes; it is invariably compulsory to state your gender when doing anything 'official': opening a bank account, renting a room and getting a job are just three examples. Amnesty International’s 2014 report ‘The state decides who I am: lack of legal recognition for transgender people in Europe’ details how “in several European countries, including Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy and Norway, transgender people cannot obtain new documents reflecting their gender identity unless they undergo genital reassignment surgeries” and sterilization.

For many trans people, there are more important things than gender reassignment surgery. Particularly if you are of colour, being trans disproportionately means experiencing poverty, unemployment, homelessness, state violence and male violence. It means being subject to a wildly high rate of mental ill health: one survey found that 48% of trans youth had tried to kill themselves, in comparison to 6% of young people generally. Meanwhile, wanting gender freedom is considered more pathological than believing, against all the evidence, that people divide neatly into two unchanging types.

Only last week the UK Ministry of Justice declined to extend legal recognition to non-binary gender identities despite being petitioned by over 30,000 people, stating that they did not see non-binary people facing “any specific detriment.” As Nat Raha explains, the liberal trans-activist push towards political rights, “viciously reproduce[s] socio-economic divisions along intersecting lines of race and class, gender, sexuality, dis/ability, nationality and immigration status.” While any meaningful trans movement must look past rights to radical action – at a basic level, lacking legal recognition means that non-binary people are closeted by law.

To be trans is to have the fight against gender oppression inscribed on your body. Jacques points out that the difficult part is not living as the gender(s) you identify with, it is living in a neoliberal patriarchal society. It is facing down the simultaneous fascination and horror with which many people regard the idea of stepping out of an assigned gender box. Intrusive personal questioning and the disproportionate murder rate of trans women of colour are two ends of a spectrum that offers up trans lives for examination through the scrutiny of our bodies.

So 'transition', 'sex change' or, to some extent, 'coming out' are cis fantasies. They are cis fantasies that obscure the processes by which cis people create their own genders. Whether cis or trans or gender non-conforming, gender is never static. Gender identity has no fixed end point: it is a lifetime of changing feelings, experiences and attitudes. If gender is a set of relationships – to ourselves, to others, to the boxes others put us in – then no adults are the same gender, really, as when they were born, and in ten years they will be different genders still. Medical intervention is not the culmination of a clear process of transition between woman and man or vice versa, it is a set of technologies that help to alleviate body dysphoria at a particular point in time. After the 'transition' is over, there's still a lifetime of gendered experience to have.

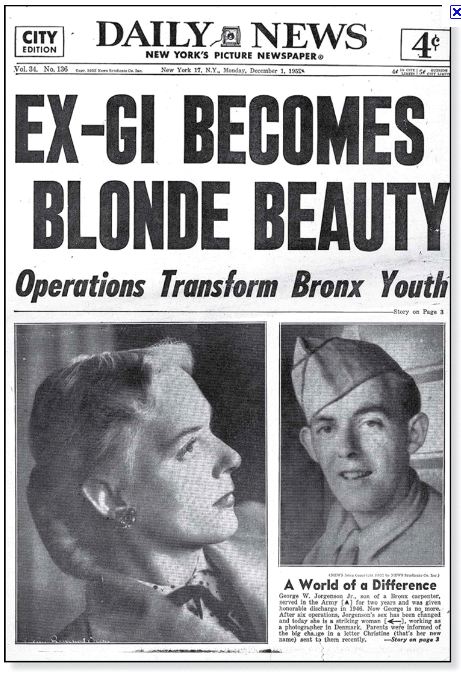

The myth is that that identity is contained within anatomy: society is fascinated with changing bodies. The lie is that this ritualised gawping is not erotic. As Jacques points out, mainstream media representation of trans people is almost synonymous with the use of sensationalist 'before' and 'after' photos that mask “processes of change, even as they ostensibly reveal them”. Trans peoples' body alterations must be seen. Trans people who do not body modify are ridiculed, or presumed not to exist. This is why some of the UK's more backwards feminists get so het up over the idea of female or lesbian penises – for them, biology is destiny.

Even more sympathetic coverage doesn't always avoid the tendency toward spectacle – deviant bodies are simultaneously put on display, and stripped of their agency. In this there are clear parallels with coverage of sex work and sex workers. As Melissa Gira Grant writes: “Aside from an origin story of her life “before,” this is where the exposition will be confined: the red light, the bed, the men, the money. Everything else is out of frame.”

But trans peoples' understandings of themselves, trans and queer communities' takes on gender, are far more developed than any other. We understand the expansive possibilities for gender expressions and experiences beyond and outside of the binary, or within it. The challenge that we present to the cis mainstream is to question not just how bodies and identities relate, but how gender identities are organised around the regulation of populations into life and death: while trans women of colour are streamlined, often, toward death, white cis men make the decisions that put them there. Fixation on the sex change obscures a whole realm of trans experiences that may have little to do with genitals.

This the context in which Trans emerges: claiming the right to self-define, to self-represent. In this it sits within the canon of trans memoirs, most famously Lili Elbe's Man into Woman and Jan Morris' Conundrum, self-authored life stories framed around being trans. Jacques sets the book up against the 'born in the wrong body' stereotype – and in doing so tries to escape from the genre's usual constraints. It is more than trope of "‘unhappy girl’ trapped ‘in the wrong body’ becomes happy woman after medical intervention"—there is art, music, there is experimentation with the trans memoir form. But by framing the book around her reassignment surgery, Jacques steps out with only limited success. Still, it's a double bind: do you start your book with what people will find most interesting/appalling, what people see as the epitome of the trans experience, or refuse to and lose readers? Will cis people still care when we stop showing them what's in our pants?

1. Cis people: I define 'cis' as labelling people who choose to live within the gender they were assigned at birth, who may or may not have a complex or antagonistic relationship with their assigned gender, but who nevertheless choose to use the terms and social categories broadly assigned to them.

Ray Filar is a freelance journalist and an editor at openDemocracy, working on the Transformation section. Their writing has been published in The Guardian, The Times, and the New Statesman, among others. They are the editor of Resist! Against a precarious future (Lawrence & Wishart, 2015), a book about young people and politics. They tweet, @rayfilar, their website is here.