Beyond Stonewall: Screening Trans* Lives, Seeing Trans* Histories

Film writer Sophie Mayer will be in conversation with Juliet Jacques about her new book Trans: A Memoir, the cruxes of writing and identity, and LGBTQ film and art at the ICA on September 25th.

In this guest post, Mayer guides us through film that re-envisions queer and gender-nonconforming people into history, upturning the selective narrative of Roland Emmerich's new Stonewall film, released at the same time as Trans. Controversial for cis-washing and whitewashing LGBTQ history, Emmerich's film has been boycotted for relegating central Latinx and black transgender figures such as Sylvia Rivera or Marsha P. Johnson to background characters in the service of a white cis-male fictional protagonist.

Before there was Heather Dockray’s awesome spoof trailer Stonewall-ish for Stonewall (Roland Emmerich, 2015), there was Before Stonewall (1984), Greta Schiller and Robert Rosenberg’s documentary about the multi-ethnic US LGBT+ rights movement in the decades prior to the fightback outside the Stonewall Inn in June 1969. And there was also Stonewall (Nigel Finch, 1995). Adapted by Rikki Beadle-Blair from the novel by historian Martin Duberman, the story is told from the point of view of La Miranda (Guillermo Díaz), a Puerto Rican-American transwoman: precisely the perspective that appears to have been whitewashed – and cis-washed – from Emmerich’s forthcoming mainstream feature.

(Heather Dockray, 2015)

Of this earlier Stonewall, Juliet Jacques writes in Trans: A Memoir: ‘I felt so inspired by Miranda and the queens who joined arms with her outside the Inn: they refused to keep quiet and blend in, knowing they could only bring about change by standing up for themselves, together, and fighting discrimination with radical action.’ What inspires her about the film becomes a manifesto for her writing: presenting her singular experience as a framework and vessel for collective discourse and action. Challenging assumptions about the memoir as an instance of the individualised, atomised form of late capitalism, Jacques mirrors Stonewall’s strategy of including newsreel footage that interweaves the voices written out of history.

Stonewall theatrical trailer (Nigel Finch, 1995)

But in the chapter ‘Home Movies’ looking at trans people in film, Jacques finds that even the 1995 Stonewall couldn’t represent everyone: ‘Stonewall didn’t feature Sylvia Rivera or Marsha P. Johnson, who were at the riots and then set up Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, to advocate for homeless queens and queer youths; it was only years later that I found out how central they had been to the struggle of July 1969.’ STAR’s print legacy has been collected by Untorelli Press in a free book introduced by Ehn Nothing. Yet despite 20 years of concerted activism by trans writers and writers of colour to re-vision the accepted history of the Stonewall riots, Stonewall 2.0 is the lighter, whiter version. So independent filmmakers Reina Gossett and Sasha Wortzel are responding with the drama Happy Birthday Marsha!, tracing Johnson and Rivera in the hours before they kicked off the riots. According to some sources, Rivera – 17 at the time – cried out ‘I’m not missing a minute of this, it’s the revolution!’

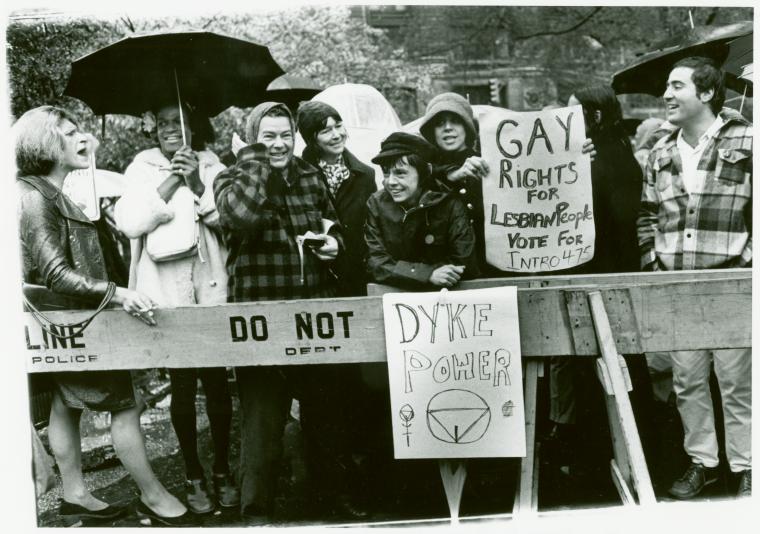

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson (far left), with Jane Vercaine, Barbara Deming, Kady Vandeurs, Carol Grosberg: demonstration in support of gay rights bill Intro 475 at City Hall, New York, April 1973 © Diana Davies (New York Public Libraries Collection)

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson (far left), with Jane Vercaine, Barbara Deming, Kady Vandeurs, Carol Grosberg: demonstration in support of gay rights bill Intro 475 at City Hall, New York, April 1973 © Diana Davies (New York Public Libraries Collection)The fact that Happy Birthday Marsha! is crowdfunding – as is Jacqueline Gares’ and Laverne Cox’s documentary Free CeCe! – at a time when levels of violence reported against transwomen of colour in the US are rising, underlines the rationale for the critiques of Emmerich’s film, including a proposed boycott.

Free CeCe documents the epidemic of violence rooted in transmisogyny through its central subject, CeCe McDonald, an African American transwoman who was imprisoned – in a men’s prison – for defending herself against a life-threatening attack.

With Sundance supporting both Sean Baker’s drama Tangerine (2015), shot on an iPhone 5s and starring Kitana Kiki Rodriguez as a trans sex worker recently released from prison, and Sydney Freeland’s Drunktown’s Finest (2014), where both director and star Carmen Moore are Navajo transwomen (nadleeh), transwomen of colour are boldly emerging into independent cinema. This can be celebrated as a new development, but it’s not a novelty. The catalogue of Third World Newsreel films – which started as a community filmmaking project in New York in the 1970s – includes Storme: Lady of the Jewel Box, a 1987 documentary by Michelle Parkerson about Storme DeLarverie, a butch lesbian and drag king who was also on the frontline of the Stonewall riots. Parkerson also made A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, among other films about black butch lives.

Storme DeLarverie (centre), with Gene Avery, Dore Orr and Tobi Marsh at the Jewel Box Revue, undated (Picasa)

Storme DeLarverie (centre), with Gene Avery, Dore Orr and Tobi Marsh at the Jewel Box Revue, undated (Picasa)Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin (Nancy Kates and Bennett Singer, 2003) is a reminder that the civil rights movement and gay rights movement were entwined, even if not explicitly, in the figure of Martin Luther King’s advisor Bayard Rustin. Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989) traces African American queer identities further back still, to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and its key figure, Langston Hughes. Struggles with Hughes’ estate over his sexuality mean that the film has still never been shown in its complete version in the US.

Looking for Langston

Julien was identified as part of the New Queer Cinema by B. Ruby Rich alongside two other directors who are part of the history of trans and queer cinema that Jacques weaves through her memoir: Derek Jarman, who shot shimmering Super-8 home movies of the Alternative Miss World competitions he co-organised with Andrew Logan in the 1970s before making his better-known features; and Jennie Livingston, director of the documentary Paris is Burning (1990), about New York drag balls and the predominantly African American and Latinx transwomen and drag queens who made voguing happen. Between the Stonewall riots and Paris is Burning, ‘a world had changed, perhaps been lost,’ to the impact of HIV/AIDS, Jacques notes. Not without its own controversy – as Ashley Clark reports, from lawsuits by its subjects to scathing critiques by bell hooks – Paris is Burning was heralded as a document of survival through the alternative families of the Houses, each with a senior transwoman as Mother.

Paris is Burning

Like Finch’s Stonewall, Paris is Burning – ‘exciting and inspiring, and full of defiance’ in Jacques’ words – offers above all a profound alternative to the stereotype of the lone trans* character in films as different as Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberley Peirce, 1999) and In a Year of Thirteen Moons (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1978): whether you read them as moving or bleak (and Jacques offers both readings), they both focus on a single character disconnected from any possibility of community. While the subjects of Paris is Burning, who have a range of gender identities, struggle against homophobia, transphobia, racism and classism, they struggle together – not least across multiple generations, with the older Mothers’ memories stretching back through HIV/AIDS to Stonewall.

Paris is Burning

The community’s defiance is predicated on that togetherness through time as well as in its present: another reason that Stonewall (Emmerich) is not Stonewall – and not even Stonewall (Finch). If, like Rivera, you don’t want to miss a minute of the revolution, skip the reductive version and check out the films above.