Postcard Chat: between John Berger and Yves Berger (Part II)

Postcard Chat

between John Berger and Yves Berger

(Part II)

A proposal. Let's take a walk along a border. The border I'm thinking about is hard to name or even to locate. Maybe it's not even a border, but never mind, I'll try to take you there.

As I'm writing at the table of this “café”, I'm listening to music. With my headphones on my ears I can concentrate better – the music helps me to cut-off, to withdraw from this place and all its distractions. The music I'm listening to reminds me of Soufi music. Such as the singing of Nussat Fateh Ali Kahn. A kind of trance. A trip … Well, this trip would take us to the border we're aiming for.

Are the stars visible these days in the night sky of Paris? If so, look-up at them tonight and start thinking - as we all know, but in a very abstract way - that they are mostly suns in other solar systems. But also keep in mind where you are, on this specific planet of this specific solar system. Now wonder about the scale of your life within the scale of life in general. Need a chair? Always better to lie down when looking at stars. Now you may be getting near the place I would like us to approach?

Let's take another vehicle. Both of us have had the experience of drawing in a life-class, that's to say with a model, someone posing, naked. And in appearance, before we start really looking, it all seems pretty obvious. We all know what's a human body, male or female. Or do we? The more we look at it and try to draw it, to “represent” it on the paper, the more we doubt we know what we're looking at. To the point that we forget, must forget, what we thought of as our “knowledge”, in order to face this fascinating mystery. And from there try to learn again.

It's true the human body is a very complex thing, and so this could explain why it remains, or rather becomes, so mysterious when we focus on it. But what about an apple? Or the way a coat hangs on a chair?

For each of those two, Cezanne and Giacometti have spent a countless amount of time and energy trying to grasp what it means, to see clearly.

And if you were to ask them, they would both say they have failed!

I came out of my mother's body. She came-out of her mother's body. And so on … We can look at it in from all sides, but there's always something too big for us in life. Too big to be able to think-it, to see-it, to hear-it. And so to be able to carry-on from birth to death, we each have to find a way to deal with this “too big”. And the least we can say is that it's not easy. Maybe specially today in this world that leaves so little space for recognizing this “weakness” of ours.

So much exceeds our understanding. So much remains open in what seems, or even is closed. This gap between our consciousness and our feelings, between the visible and invisible, between the said and unsaid, leads to a kind of vertigo. A vertigo that's not far from praying, or from madness. That's the zone where I would like us to meet. Are you coming?

With love,

Yves

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

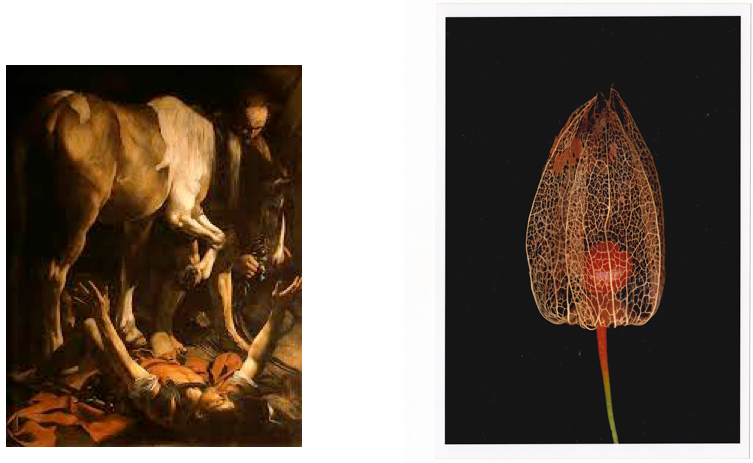

So here I am with you in the zone which faces the “too big”. And I've brought with me two images because they have been on my table for months and I was glancing at them most days, and because they refer in their own way to what you are saying.

The first is a photo of a plant by Jitka Hanzlova– the Czech photographer of forests and horses! This image of a plant, when seeding, is as mysterious and as vast and as humbling as the sight of the stars in a night sky, don't you think? So physical scale has little to do with the intimidating ”bigness”. What is intimidating is perhaps the endurance involved?

The second is a painting we both know so well by Caravaggio. I send it because it depicts exactly that moment of vertigo or prayer which you refer to. St Paul, if you like, has just looked at the stars!

Yet what is so striking is the way in which Caravaggio has painted what surrounds Paul – a horse, a man, a cloak. These banal, everyday “presences” are painted with such wonder and intensity that they seem not ordinary but extraordinary. The horse's lifted foreleg and the man's standing leg are oceanic in their depths and their force. They are painted like a tempest might be painted.

But after saying all this, here we still are in the zone which faces the “too big”.

When we face the “too big”, are we not really facing the “too brief”, that's to say ourselves, our minds, who have invented the measures – like “light-years” - for measuring the bigness? You say this too. But what I'm hinting at is that the bignesses are our invention, are part of our Being.

Then, if we follow Spinoza, and suppose that everything which exists is indivisible because this everything constitutes a whole, we see the bigness as something surrounding us, including us, rather than confronting us. And this is the mystery that art strives to present to us.

The figures which you are painting are messengers of this by their very presence. And their gestures show us or remind us of something we half-know.

We acknowledge and recognise the immense whole with our actions (gestures) of solidarity and sharing. Such actions embody hope – which is as big (not by what it promises, but by its very nature) as the Big Bang, 13.8 billions years ago!

You still on the border?

With all my love,

J

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

Me still on border. And where I stand it happens to be a bridge. So I lean over and take a look down below. My God what a gap!

It's true I can believe all is part of an immense whole – gap, bridge and me included. Just as I can say: “All that happens had to happen”.

And if I was as wise as the gap is deep, I would stick to that celestial point of view and it's eternity. It's an aim that's worth working for, as it is not a given!

But my feelings often bring me down. And then the depth appears to be vertiginous, the parts all separated. The heart beating faster with excitement and fear.

It's not a question of truth or reality, but rather a question of how we make an arrangement with ourselves in order to live. Or, more precisely, in order to stay alive.

Recently I saw the film Le Grand Bleu. I had seen it long ago and something about it always stayed with me. Not that it's a great film, but in it's way it's about this zone we're talking about.

The two main characters are free-divers, who push back the limits of their bodies by going down as deep as possible in the sea, using only their capacities for apnea. The longer they stay under water, the deeper they go, the more dangerous it becomes. They are reaching and playing with a limit. At some point one says: “the hardest thing when you're down there is to turn around: you need a good reason to come back.”

And finally the attraction of this limitless and dark world, a hundred meters below the surface, is so strong they offer themselves to it.

I think I like to recall that film because I feel something quite similar when painting in the studio. And about Caravaggio's painting you talk about an oceanic depth!

The plant Jitka took a photo of, which you sent me, is called in French:”un amour en cage”. Both the image and the name set us wondering, asking: How? How can it be? True names sometimes do this: they double the mystery of what they are naming with their own mystery. So if you look outside you will see the witchazel is in flower, next to the waking-up strawberry plants and the still asleep walnut tree. (walnut literally meaning “foreign nut”...) And equally you won't miss the noisy magpies (“Pie” being the old French word for those birds and apparently “mag” was a slang word to name qualities generally associated with women, like chattering!).

So now, after this dive in the sea and this walk in the garden, I leave you in the hands of a friend who's taking you to a party, a very special party, located... guess where?

Love,

Yves

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

21/03/15

Dearest Yves

Like you say: the question is of staying fully alive! Francisco took my arm and led me to The Burial of the Sardine. It's so pulsing with energy, that painting! We don't talk because he's stone-deaf, and was when he painted it. Frankly I don't think the subject of the popular feast of the Sardine on the last day of Carnival before the first day of Lent, is very important here. For Goya it was another scene of human craziness. As I went on looking at it, I was overwhelmed by the din, by the noise, the incomprehensible noise the huge crowd is making. And I imagine that when you are stone-deaf, there may be situations whose utter incomprehensibility is like a deafening noise!

For those who are at The Burial of The Sardine, it's perhaps like a wild Rock Concert, but for us spectators it's a senseless, continuous roar. As Goya said: “The sleep of Reason produces monsters.”

(My God! Look at what's happening in Israel and in Palestine; every pomegranate is bleeding...)

I too remember the film of Le Grand Bleu. And if I'm not wrong, what partly tempts the two free-divers to stay there in the depths and not come up to the surface is – the silence.

And so we have din and silence. Din obliterates explanations; and silence offers a continuous questioning present. Neither can help us much to be fully alive.

What can? Maybe asking questions. And questions are not only verbal. When you are painting, you are asking questions one after another.

The paradox about asking questions lies in the fact that the questioner believes that it may be possible to find or come upon an answer. And this is a kind of faith.

A kind of faith which is totally absent in most church pictures, but which is there, for example, in Morandi's jugs and bricks. No?

Yes, it's true that names sometimes double or amplify the “meaning” of what they're defining. Sunrise. Midday. Dusk. Nightfall. The Small Hours. Tomorrow...

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

25/03/15

Papa – to “morrow”, yes “terday”!

(The definition of “terday” found on internet gives: British slang for Today. It is used mostly in the South, around East Anglia area. Pete -”I had sex with the sister terday.” Dan - “I did that yesterday!”)

I'm glad Francisco took your arm. It's true you've known each other for a long time. When you and Nella wrote Goya's last Portrait, you spent many days and many nights side by side. I guess he hasn't changed since – as he is dead – but you've become an older man. Did you tell him about your difficulties about hearing and how your relation with sound has changed?

I've always heard you address the Old Masters or writers or thinkers, men you admire and feel gratitude towards, as if they were comrades, standing just there, by our sides. Their physical absence – and most of them were dead long ago – doesn’t make the slightest difference. What has been lost is insignificant compared with the ongoing presence of their lives. A presence established not only by the works they left, but by the intensity of their impulse towards what they sought. The number of ramifications between one life and others is incalculable, just as the shapes in which life exists are unpredictable.

So it could be a game between us – of going to a Rock concert with Goya, or of knocking at a door in the Via Fondazza in Bologna, and waiting for Mister Morandi to open it. A game. A form of make-believe but nevertheless not gratuitous. For kids games are more real than most of so-called reality.Let’s go back for a moment at The Burial of The Sardine: I agree Goya saw it as “another scene of human craziness”, but it’s different from many others he depicted. Battles, fusillades, misery, hunger, illness, the domination and narcissism of the powerful, the absurd rules that held all that world together – all this cruelty of the human condition afflicted Goya deeply, so deeply he was considered insane.

“Lucidity is dangerous Francisco!”

“More than I can say...”

But here, at the burial, it's a carnival. People are playing, joking with and about human craziness. They take the Mickey out of their world! For a moment they join Goya, for they recognize the same thing. They witness the same thing. But when they decide to laugh together, he turns around and starts crying.

“Some of your paintings, Francisco, are made out of tears”.

“They didn't stop, I prayed in despair, but they didn't stop...”

To keep faith as we face everything, to ask questions hoping we may learn, to learn to ask new questions in the silence or the din: do we have another choice ? Is there another way towards freedom beside this narrow path?

“I've lived here almost all my life.

Since father died anyway. My brother

Giuseppe never saw this place. Later,

Anna, Dina, Maria and I found a way

to arrange our lives in here.

Protected from the terrible sunlight (true din) and

preserved from the obscurity which swallows

everything in the unknown (the silence)

Have a seat! This is my shelter.”

Mister Morandi, you are the soul brother of Fran Angelico!

“I've always dreamt of spending a night in one of his cells, even though I dislike leaving my home...”

In our library in Quincy—mon ancienne chambre—I hung side by side four still lives by Sven. You see those small paintings on paper he did with oil sticks, quite late in his life? I love them always more. Maybe because their fragility never fails... Fails to what? Tell me about your friend Sven Blomberg. What was his example and his faith?

xxx

With all love,

Yves

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

9/04/15Dearest Yves

Oddly enough, I didn't tell Goya that, as an old man, I have become hard of hearing. Maybe I'm wrong, but I have the impression that he entitled one of his “capriccios” “The deaf talking to the deaf”. In your old bedroom there's a book of all his capriccios. And I also have the impression that you looked at this book when you were still very young.

What you say about our artist predecessors seems to me right and important. ie: that their “impulse” is even more encouraging than their works. And what their “impulse” signifies is their devotion to posing questions and to searching for partial replies.

Yes, the carnival crowd are taking the mickey, and putting their arms round Francesco and sharing his laughter. And after a moment, tears come into his eyes. It's intriguring that both laughter and loss provoke tears.

I shut my pen and laid it on this sheet of paper. And when I looked next, it had done this. Curious?

And my fingers are stained with Schaeffer black! (Somebody pointed out to me the other day that Schaeffer in German means Shepherd. ie Berger.)

In the photo you sent of Morandi, he's, as you say, listening as much as looking. Listening to the “conversation” between objects. Between two jars. Between satellites and the earth...... between a stylo and a clean sheet of paper?

Philosophers search for answers; artists seek and confront doubt. Scientists establish formulae; artists find metaphors.

You ask me about Sven. What was his example and his faith, you ask. In his way of life he was unique and I've never met another painter quite like him. Perhaps he had a little in common with Giacometti whom he admired and whom he had known when he first came to France in the late 1940s. He did not paint to produce paintings. His studio was an upper room in the outhouse of a tiny farm, and was scarcely larger than a garden-shed. He never invited anybody to climb up into it. His “finished” paintings he took off from their stretchers and stacked in a vegetable “loft” for onions. His chosen way of life served his mystical love of Nature – although in appearance he didn't look like a mystic, but like an onion-seller. His mystical love had something parental about it – as if Nature was the mother of everything and, at the same time, a child who needed protection. And both roles implied a constant conversation. When he was painting, he was tending the land in another way. He had no ambitions about exhibiting or selling his work. If a friend wanted to buy a painting (he had a good many friends from Paris who came to visit him in Lacoste and they mostly belonged to philosophical milieux around Garaudy and Merleau-Ponty) if a friend wanted to buy a painting, he would put a high price on it but indicate that he was making a sacrifice because the painting would no longer be there. Otherwise he, Romaine and their daughter Karine contrived to live without money. For transport he had a bicycle. Later I got him a second-hand 2CV. For him the act of painting was the act of kissing nature. But, as happens in kissing, perhaps Nature was kissing him – her tongue thrusting towards his throat. He loved birds; they were like postmen.

The real postman refused to drive down the 1km lane to his house (like yours to Vers le Mont) and he arranged a wooden box where the lane joined the tarred road. His one luxury was his library. He was very well-read and the library was the largest room. Poetry and Philosophy. Both he and Romaine would read whilst eating a meal, more often than not prepared by Sven.

Perhaps this tells you something about his example?

Over to you.

With all my love,

J

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

01/05/15Papa,

I'm on my way home, in the train from Milano to Geneva. The landscape moving outside the window is grey and green. Grey because of the concrete and the roads, and grey because it's a grey day – as if the sky had abandoned it's job and wanted to do nothing (we're the First of May!). Green, fresh green, because it's the colour of spring...

I love your description of Sven's way of life. And indeed it makes me feel the example he set and the faith he had. A faith that smelt of onions!

In Milano, as you know, I was invited to talk at the Bocconni University (a private university well known for preparing students to be the economical leaders of tomorrow's liberal and global world...) I was invited to talk to a group of student - researchers as they call themselves – about my practice as a painter and my “way of life” as an artist today. The meeting happened and they were happy, but mainly I feel it was a failure. And I will try to tell you why. (The train is now passing along the lake before Domodosola with those little village-islands on it. You see? I know you took this train many times in your life...)

I had spent quite some time preparing for the talk. I had chosen to use several sequences of photos showing my paintings “in progress”. You know those photos because I took them at the end of each day's work, to send to you via email, for you to see what I had been working on, and for us to talk about it when we phoned each other in the evenings.

For each painting (finally I chose only 3) I had a series of 8 or 9 photos, sometimes taken over a period of several years, of different stages along the long road that eventually led to the achieved painting. And showing them I realized I hadn't measured the risk of revealing such images in this way.

Our dear friend Maria Nadotti was the first to point out the problem: those pictures were misleading. First because they gave the impression of a linear process, as if Time was an arrow, whereas the experience we have of it is made of folds, and folds within folds, sometimes touching one another.

Secondly, they were misleading because of the nature of the photographic image as distinct from a painted image. When looking at a reproduction we are aware we are not looking at the “real thing”, the unique, original painted canvas, with it's presence, or as your friend Walter B said, it's aura. Here, with these pics of a painted image that no longer exists – or is only “underneath” the final painting – we are in a quite different position. What we see pretends to reveal the unseeable, something like what happens in pornography, where one is offered what's behind, behind nakedness, behind intimacy. Of course it's a lie. A lie we, as the animal we are, partly believe in...

(For the second time, a patrol of Border Control Police took a black guy off the train, after going through his luggages with blue plastic gloves.)

What I'm trying to say above is that the kind of entry those photos made into my painter's practice, led the viewer to a sort of voyeurism. And therefore to ask themselves wrong or unnecessarily questions.

I had hoped these pics – so useful for me in our exchange – would have been a support for my talk. In fact, I had to fight against their simplifications when talking.

I think Sven, with his practice of kissing nature, would have foreseen my mistake. He who didn't let anyone enter his studio.... But I'm glad now to have learned something from it. (We should build monuments in honour of our mistakes, for it's most of all from them that we learn, no? Let's propose it to the Ministry of Culture, what do you think, next to the Monument for “Le Soldat Inconnu”? !!!)

The grey sky has come down even more and now it weeps drops of rain. And those drops, on the windows of the train, move along, rolling almost horizontally, in the opposite direction to us. If I say it's due to the effect of gravity combined with speed and the nature of water and glass, does it diminish the poetry and the mystery of such an event? And I look at people looking out of the window, and say to myself: How beautiful …

Flowers. Drawing flowers. Painting flowers. Celebrating flowers. I think that could be the next chapter of our exchange. What better to do in the month of May?

With all love

Yves

PS: Under this sky, the Leman Lake looks like the sea.

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-

Visit the Brooklyn Rail to read Postcard Chat Part 1.

John Berger launches his new book Portraits: John Berger on Artists, a collection of his writings on art and artists edited by Tom Overton, at the British Library on September 18th with Ali Smith, Gareth Evans and Tom Overton.

The Art Space Gallery in London will present 'For Other Eyes', a selection of Yves Berger’s new work from September 18th to October 16th. For more information, visit Art Space Gallery.