If you focus on the performance when you think about sex work, and don’t think about the lives of the workers themselves, the management has won - London Review of Books

You're at work. You’re good at your job and work long hours – your boss has little to complain about. You get on with your colleagues and have them over for dinner now and again, but your boss doesn’t like you seeing them outside work. He doesn’t like that you’re a member of a union either, and that you’ve told your colleagues about it. He starts harassing you. It begins with a sexually inappropriate comment here and there, and comments about your weight. It turns out he’s pressuring some of your colleagues to have sex with him. One day, after a night shift, your lift doesn’t turn up, so your boss drives you home. He threatens you: he’s watching you, he says, and if you don’t look out, something might happen; you’ve spent too long in your ‘comfort zone’ and someone needs to take you out of it. The harassment continues, until you quit. You want to file a complaint. It seems like a solid case. You’d win, right?

Not if you’re a sex worker.

It is rare to read an essay outside of the blogosphere that gets it so right about sex work. This powerful piece by Katrina Forrester in the London Review of Books looks beyond sexual morality, trafficking and the ‘SCANDINAVIAN MODEL!’ headlines; instead, focusing on how sex workers’ are treated and the basic rights that they should be afforded.

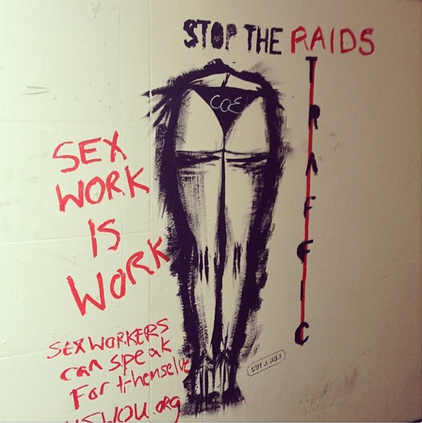

Sex workers are workers. Their workplaces should be safe, and they should have the same rights – including labour and employment rights – as everybody else.

This is the central argument of Melissa Gira Grant’s book Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. Sex workers exist. So do the many victims of human (including sexual) trafficking. But they are not necessarily the same people, and sex workers are not all victims who need to be saved. Some of them might be victims: raped and exploited by pimps, johns and police. Some of them might be empowered and love their job in the way we all wish we loved ours. But between the victims and the empowered, there’s a whole world of sex workers who do what they do and get by. Some might like their job, sort of, some of the time. Many might not like it much at all, but prefer it to their other options. Others might want to get out, but not really know how. People experience the conditions of their labour in a huge variety of ways, and in this, sex workers are no different from the rest of us.

...If sex workers claim they aren’t victims, we expect them to say they chose sex work voluntarily, that they find their work fun, or a therapeutic public service, that they are empowered. We’re not satisfied if they say that it’s a crappy job, but they’re doing OK. But why should workers have to be having fun, or be satisfied with their job, before they can earn the right to join a union, or have legal protection from violence? ‘Sex workers,’ Grant says, ‘should not be expected to defend the existence of sex work in order to have the right to do it free from harm.’ Ignoring the economic rights of sex workers also denies a basic fact: there’s a huge sex industry out there (that some see as simply a part of the mainstream media), the products of which many people comfortably or shamefully consume, as free-riding voyeurs or as paying participants. Yet few are willing to move beyond their guilty secrets to discuss how to protect the workers who enable them.

Underneath Grant’s strategically inclusive argument lurks a harder political critique of the transformation of politics and economics since the 1970s. Over the last forty years, international politics has become more and more concerned with humanitarian issues. The view of women as victims of violence and objects to be trafficked can be seen as part of this trend. Violence against women is a major global problem, but the focus on humanitarian issues like violence (and the framing of violence against women as a humanitarian rather than a political issue) distracts from the political and economic conditions that give rise to them.

She goes on to talk about how humanitarian organisations are now responding to sex workers: "[they] now recognise that the conflation of sex work with sex trafficking has gone too far", and how feminists of the 1970s differed so much in their reaction to sex workers: “the mobilisation of the English Collective of Prostitutes, protests against police brutality by French sex workers in Lyon and the transition from the ‘state of being’ of prostitution to the ‘form of labour’ that is sex work”. Gentrification, for example the Soho raids in London earlier this year, has coincided with the visible shift of commercial sex from the streets to the internet. Old dangers are replaced with new ones: “the risk of anonymity becoming renown at the click of a mouse, and the increased threat of state surveillance, which, as long as sex work remains criminalised, is a very real threat to freedom”.

We could continue to quote chunks and chunks from this excellent essay but a) plagiarism b) it’s best read in full, as Katrina Forrester intended.

"The way we feel about sex shouldn’t be imposed on others. It certainly shouldn’t be the basis for law."

Playing the Whore: the Work of Sex Work by Melissa Gira Grant published earlier this year.

Blame it on the management: Katrina Forrester for the London Review of Books.

Further reading:

Anti-work sex laws hurt the women they are meant to protect // Melissa Gira Grant writes for the Guardian

Melissa Gira Grant debates sex work with Mary Honeyball MEP on Channel 4 News

Either sex workers are in the debate, or they're not // an interview with Melissa Gira Grant in the Observer

Debunking myths about sex work // Melissa Gira Grant interviewed for New York Magazine