Look within: literary diaries and the culture of narcissism

Our appetite for literary diaries has never been greater, with TikTok and Twitter feeds filled with snippets of writing from Virginia and extracts from Sylvia Plath’s food diary. But what can the contemporary desire for the diaries of others tell us about our individualistic society?

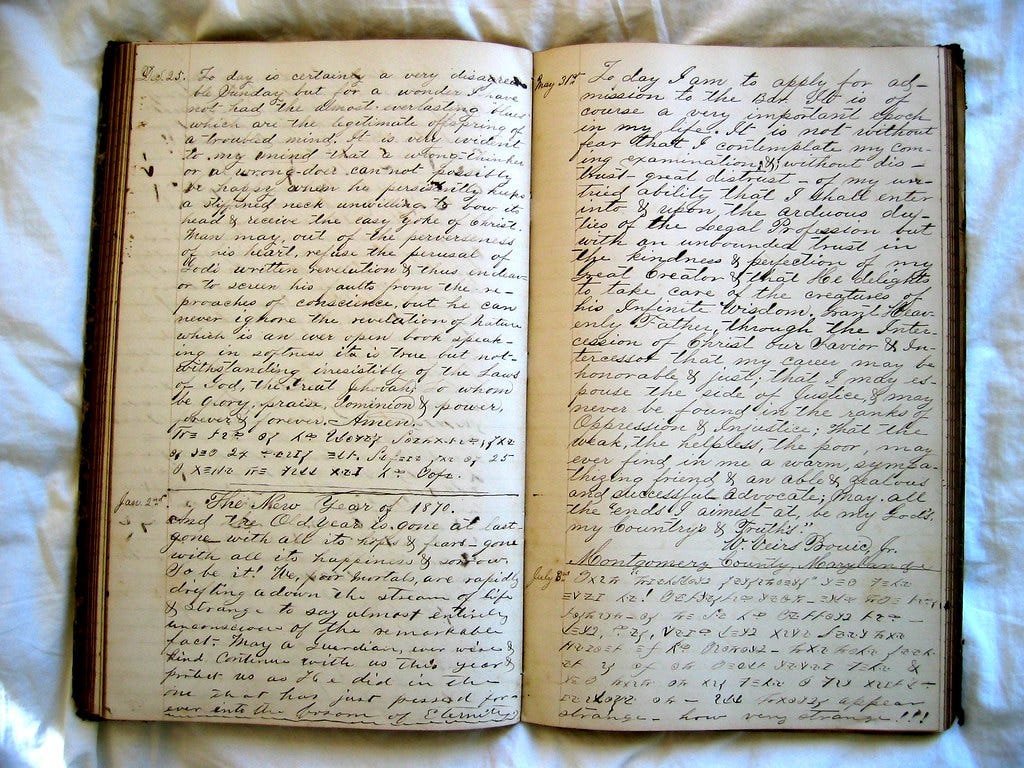

“I've fallen in love or imagine I have,” wrote Leo Tolstoy in his diary 172 years ago. “Went to a party and lost my head. Bought a horse which I don't need at all.” It is a quote that emerges on Twitter every few weeks, and even though it is nearly 200 years old, it doesn’t matter to the fans who find it relatable (“I have an aunt who once bought a car on impulse, and I was like, who does that???”, went a typical reply). Tolstoy isn’t alone in gaining dubious new levels of posthumous fame through his innermost thoughts. Thanks to the internet the diaries, letters and notes of our favourite authors and thinkers have become fodder for “corecore” collages, relationship advice, creative inspiration or, in the case of Tolstoy and his accidental horse, just a funny kind of shorthand for communicating with each other. Literary diaries have become a meme.

Along with Tolstoy, there’s Sylvia Plath’s food diary – “Ted loves deviled eggs the way I make them with onions & mayonnaise. 7/14/56” – Auberon Waugh’s state of constant exhaustion – “for a week I’ve done nothing at all” – and the rare happy moments from Kafka – “anyone who cares about you has to realise that you need a little looking after” – whose letters to Milena are regarded as the ultimate expressions of love. The indisputable apex predator of the literary diary though, is Virginia Woolf, who wrote obsessively in diaries from her teenage years until just four days before her death. The 42-year sum of that journaling, or diary writing, or note taking, was consolidated by Granta this summer, who published it in its full “unexpurgated” five volume entirety.

Our appetite for literary diaries has arguably never been greater. But our choice to repackage them in collectible volumes – disregarding the dubious morality of selling off private diaries for profit long after the death of their creators – or memeable tweets betrays more about why we enjoy them than might think.

The digital world we inhabit, we’re frequently told, is a phenomenally lonely one. While we’re finding relatability in centuries old chronicles of solitude and gloom, love and connection, we’re ever more unable to communicate with each other on a meaningful level. While we’re pining over declarations of devotion from Kafka and Nabokov, we’re setting our text messages to “read once” and allowing the art of love-letter writing to fall almost entirely out of use – far too exposing in the age of the dating app screenshot industrial complex. Although we’re constantly reminded of the vague “mental health benefits” of journaling, the journals we keep and are encouraged to keep make us feel less “seen” than the diaries of long-dead writers who had never seen an iPhone.

It would be easy, then, to say that we like these quotes purely because they are call-backs to a more analogue time. It’s certainly true that as our world has become digitised and ostensibly ever more connected, the art of keeping a journal has changed beyond recognition. “Shadowwork journals” – diaries created for the specific function of addressing our past traumas and working through them – frequently trend on TikTok. We’re served SEO recommendations for “the best bullet journals”, or told “why sleep journalling might be the key to getting the best snooze of your life”. Vogue tells us to make keeping a diary your New Year’s Resolution. In June this year Apple even introduced a journaling app on iOS (you can optimise this further still, with 15 of the best journaling apps to make self-reflection more convenient).

The point in modern journaling is not to write for yourself, for the joy , but instead, as Jia Tolentino writes, to be “always optimising”. The journal is metabolised now as a tool to make us better, more productive people, who sleep well and use exercise logs and stick to their New Year’s Resolutions and update their phone software regularly. Perhaps then the reason why the diaries of Woolf, Plath and Tolstoy appeal to us is because of their profound honesty. Less contrived, they hark back to a WeWork-less, more analogue time. A time when there was less pressure to monetise everything.

And whether it's the fault of the internet or something more insidious, it’s true that we live in a deeply individualist society, an era where everyone can be the “main character”, where one should “romanticise your life”. These internet aphorisms are, ultimately, meaningless. Being the “main character” is really just internet speak for rampant individualism, for imagining yourself as the centre of every event and interaction. “Romanticising your life”, as the myriad videos on social media exhort us to do, are as inspirational as they are bleak: filled with videos of young women cleaning their flats, making coffees (you can’t afford Starbucks every day, after all) and stretching at the gym. Although packaged and marketed as self-care, they’re little more than conduits for the attention economy that online influencers have gifted us.

Between TikTok and Twitter, our modern-day diaries are the outward facing, bitesize equivalent of what Susan Sontag wrote in her own. “In the journal,” she says, “I do not just express myself more openly than I could to any person; I create myself”. But now we create facing an audience rather than ourselves. We parade our finances for an audience who receive the vicarious thrill of reading through someone else’s “money diaries”, if only to uncover that their lifestyles are invariably financed by mummy and daddy. Our main character driven social media era is, then, merely the bastardised end point of the commodification of both the self and of the diary format. While once it was only in your journal that you could become the main character, now we each perform to screen or camera for an audience of millions. Rainer Maria Rilke did not have TikTok.

It’s easy to fall into misanthropy though and attribute our love for historical and literary diaries merely to loneliness and narcissism. You could look at the popularity of the literary diary online and make the case that, for better or worse, through them we’re at least able to find some connection and poignancy, an ounce of humanity in these snippets of writing, even if we can’t enjoy the same by actually speaking to each other. Journals give us an insight into the hidden humanity of other people. books are written with a view to be published and edited and are sanitised in the process; journals aren’t. They feed the impulse in us all to see people’s inner worlds and thoughts.

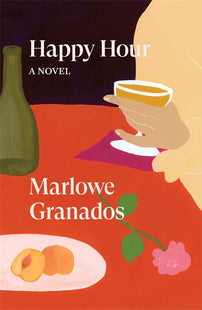

[book-strip index="1"]

And as we’ve normalised the performance of the self online, this impulse to see rawness and humanity, when we can indulge it, has an even more powerful effect on us. Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost, her unflinching account of her two-year affair with a younger married man published by Fitzcarraldo last year, fascinates us precisely because , because she hadn’t made any attempt to hide the pathetic, the limerence, the mistakes. Ernaux’s work captivated readers, particularly younger readers, who had come of age in the era of online faux-authenticity and the performance of the “best self”. People feel, to borrow another online buzzword, “seen” by Ernaux’s messy reality, so far removed from the self we’ve become used to.

Is it any wonder then, that we want more of the same. When we’re expected to put forward our best selves, to optimise for daily life, it is in diaries that we can hide those parts we deem ugly, self-defeating or unproductive. John Steinbeck’s journals, up for auction in New York this month, are not a chronicle of his successes but of his failures. “I don’t suppose anyone has ever so hated a year as I hated 1948. It is with a great sense of relief that I move into 1949. No matter how bad it is, it can’t be as bad as ’48”, he writes. It’s hardly classically inspirational stuff; all the same, a fan is expected to pay around $1 million for the privilege of owning them.

Posting memeable quotes on our public-facing profiles is a reminder that we’re more than captions for monthly Instagram photo dumps and angry tweets about gig workers. They’re reminders that other, greater writers and thinkers have endured bad days, so we can too. “In the diary,” Kafka wrote, “you find proof that in situations which today would seem unbearable, you lived, looked around and wrote down observations, that this right hand moved then as it does today.” Even the silliness of the quotes picked up by the social media machine reveal hidden depths; Sylvia Plath’s food diary, for instance, is not so much about what she eats and doesn’t eat as it is about love, connection, feeling. “I went to Ted, utterly shattered, & asked him to tackle the veal chops. And burst into tears”.

And if we embrace, Sunny Side of Franz Kafka style, a happier reason for the popularity of literary diaries online, then we could argue it's an example of innovation rather than decline. While many of us don’t keep the kind of deep and meaningful and funny and revealing diaries that Woolf wrote five volumes of over four decades, we’re at least interested in bridging the gap between the analogue and digital and finding a new way to write about ourselves and our lives. The journaling subcommunity on Reddit, for instance, is among the 1% of most popular communities on the site. At first that feels incongruous: can you realistically crowdsource a way to access your own inner sanctum? But a more generous reading would see it as beautiful; forced online and unable to properly connect with each other in real life, these posters are trying to find communion in the most individualist practices. In an article arguing for the sanctity of journaling in the age of public content, Rachel Schwartzman, creator of the podcast Slow Stories, writes that journaling is “one of the rare opportunities when what I share won’t be commodified or applauded. There is no ‘look at me,’ only ‘look within.’” The Paris Review has its own diary column which republishes historical and modern-day journal entries from writers across the world, bridging the geographical and historical gap between.

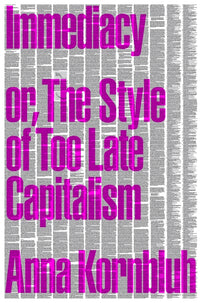

[book-strip index="2"]

Of the four reasons George Orwell proposed for writing – egosim, aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse and political purpose – diary writing could spread itself across each of them. Our interest in literary diaries of the past feeds a hunger that BookTok can’t fulfil. They’re life-affirming, even in their darkest moments (“I meant to write about death, only life came breaking in as usual”, Virginia Woolf recorded around the time of her 40th birthday). It might be in the moment the ultimate individualist practice, but somehow in our peak individualist age, these journals have allowed us to find a retrospective connection with each other. Where they might have been chronicling lives filled with nihilism and absurdity, we find relatability. Although it’s inward facing, it allows us to see each other, just 172 years later. Patricia Highsmith probably explained this dichotomy best in her own diary, although she couldn’t have known that’s what she was doing at the time. “My appetite is twofold”, the 20-year-old writer notes. “I hunger for love and I hunger for thought.” Still, it is probably for the best that Patricia Highsmith did not have access to Twitter.