FELA KUTI: An Honest Man

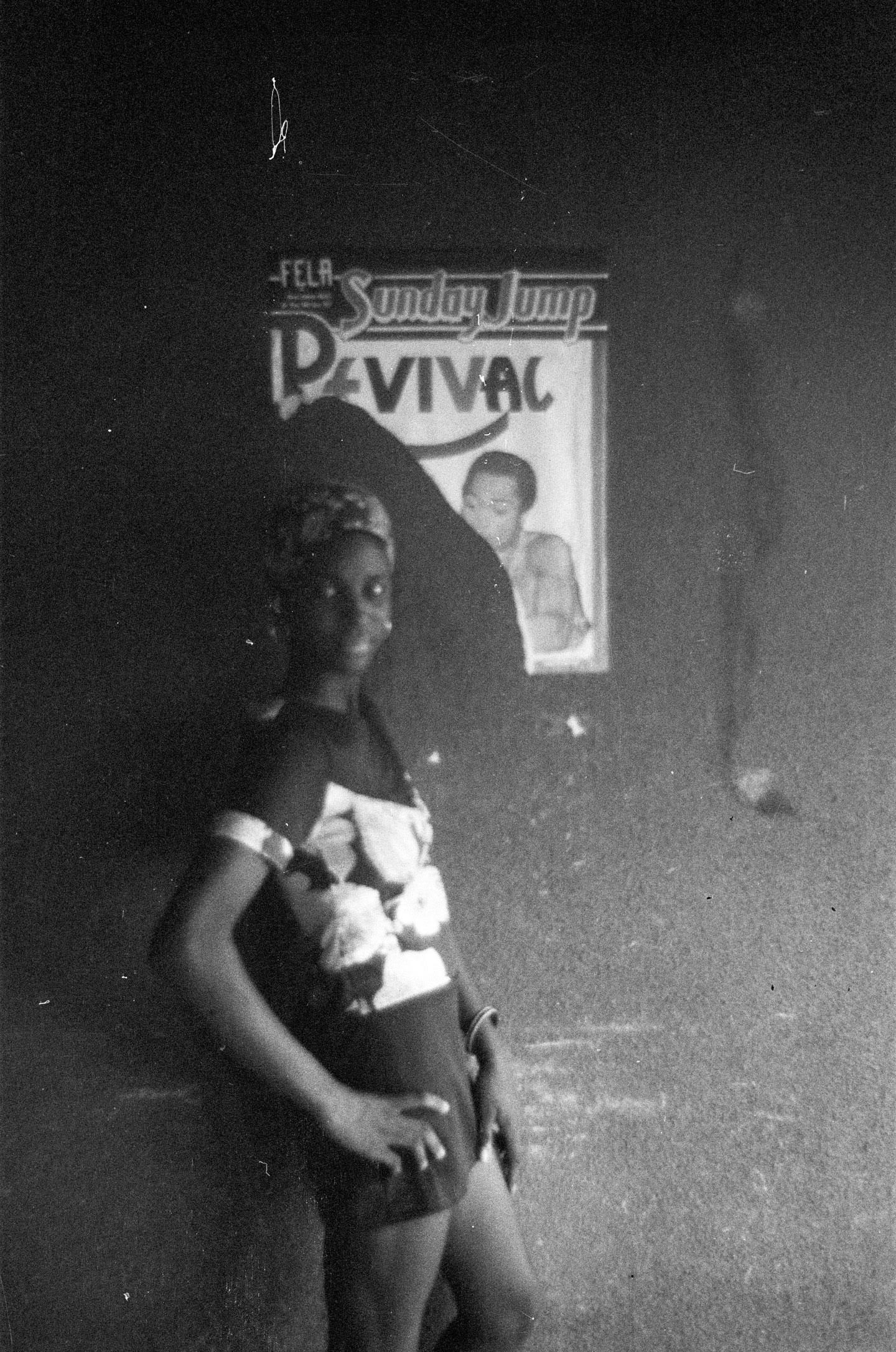

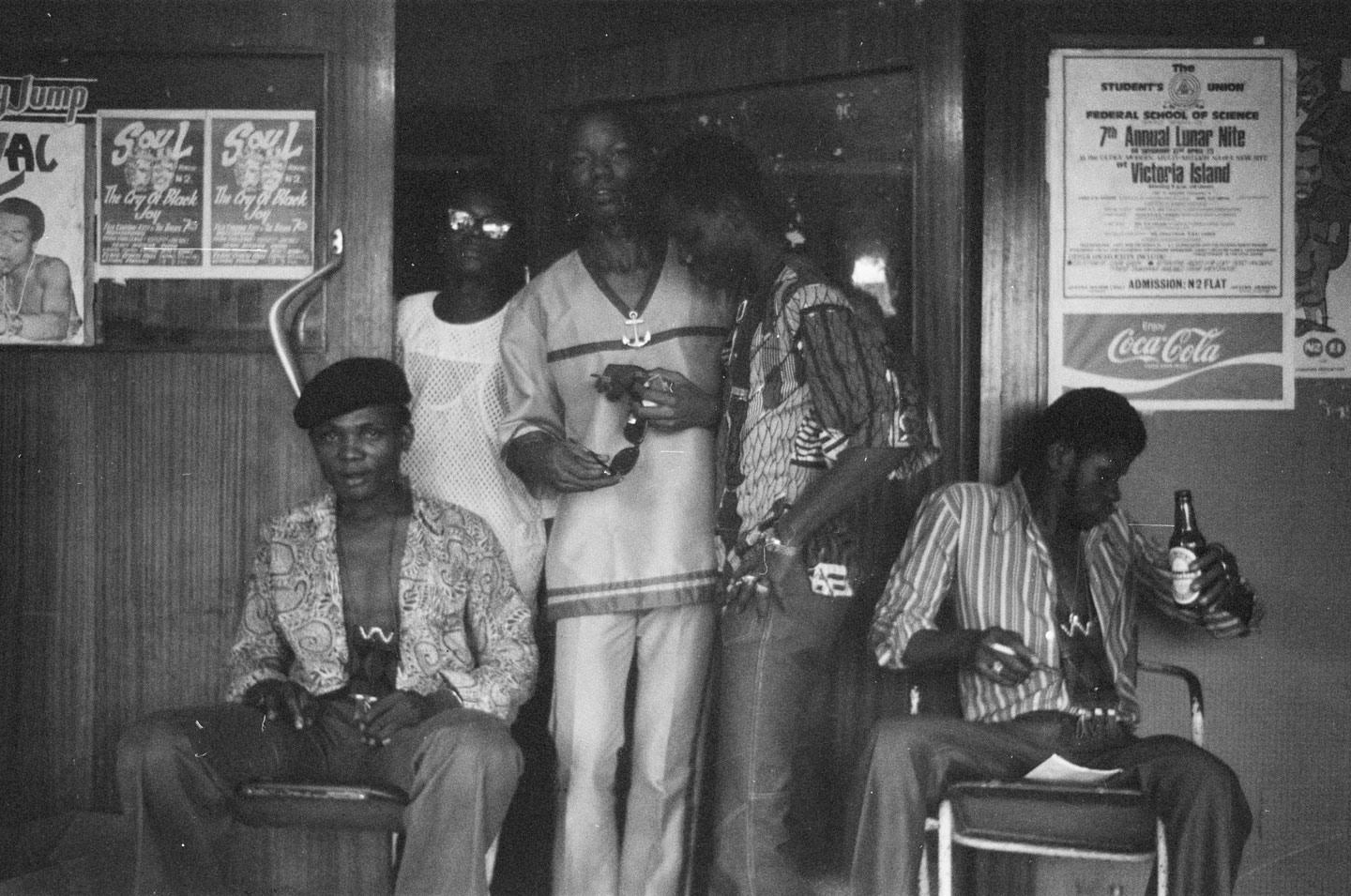

On the publication of a new collection of writing, John Howe recalls his encounter with the father of AfroBeat at the Shrine, Lagos.

This article comes from Bricolage, a collection of work by journalist and writer John Howe (1938–2018) that covers topics ranging from cars to psychology to Notting Hill’s counterculture to African politics and culture. Written mainly between the late 1960s and 2010, the essays contain many resonances for the world of 2020, notably around race relations, postcolonialism and globalisation. Some of the texts were previously published in the mainstream and avant-garde press, but many are presented for the first time.

The book is £10, with all proceeds from sales going to the Windrush Justice Fund, c/o the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants. Buy the book at http://www.bricolagebooks.co.uk.

*

FELA ANIKULAPO KUTI: An Honest Man

Through an accident – performing a service for a friend of his in London – I was invited to stay in Fela’s house the first time I visited Africa. In 1973 the naira was high, Lagos hotels were expensive as well as bad and I was not rich, so I accepted. For six weeks or so, off and on, I was treated as a privileged member of Fela’s entourage and spent much time in his company. We were six weeks apart in age, enjoyed one another’s conversation and had many noisy arguments.

Despite the inconvenience of my presence, other members of the very large household eventually tolerated me, and I learned a thing or two. One was that sooner or later I was going to have to amuse people publicly to show that I wasn’t just a bore. ‘You’ve got to go in for Worst Dancer,’ people said when they had seen me dance.

Worst Man Dancer, accompanied by Best Woman Dancer, was a late- Friday-night competition at Fela’s Shrine club, then in Surulere. Another turn was a competitive karaoke act by his friends JK and Feelings Lawyer, singing Fela’s current hit Gentleman. The Worst Dancers, often the same three guys, were of course actually very good dancers, good enough to dance comically on purpose. ‘I’m very shy,’ I whined. ‘I’m not good enough for Worst Dancer.’ But they were adamant. ‘You’re a natural,’ they said unsmilingly. I was to be a good sport. My heart sank.

Well lubricated from the bar and the back yard, I gloomily took the floor with fifty or sixty competitors. Three senior dancing girls moved about the floor and conferred, choosing the finalists. They ignored me. Saved! I headed for the bar in relief. But when Fela announced the finalists’ names he added: ‘It is my privilege, as master of ceremonies, to name a fourth finalist ...’ He was chuckling. Shit! I was in the finals. The orchestra revved up and the seven of us took the floor, each dancing alone. One by one, Fela called the finalists on stage to catch the footlights. He left me till last.

Late Friday night at the Shrine was always one of the world’s most mind blowing musical experiences. In the original Fela’s sound, of which one often hears echoes these days in other people ’s music, and to which no recording has ever done justice, had a uniquely magisterial, scowling grandeur. At full volume, ten feet in front of the whole orchestra and surrounded by its speakers, the sound would pick you up and flog you around like a housewife dusting a doormat. That’s what it felt like when it was my turn to cut loose for the audience. I mean, I was really dancing well.

By the end of the number the whole house was on its feet, shouting my name through helpless tears of laughter. People kept coming up to me the next day and saying how funny I had been. I can still hear Fela’s malicious baritone giggle as he gave me my prize: a Joe Tex album, stolen later that night before it could be played. We have been friends ever since, little affected by the long pauses between meetings. I am sorry that there will be no more of them.

Names and origins

Olufela Oludotun Olusegun Ransome-Kuti changed his name to Anikulapo Kuti at the end of the 1970s. ‘Anikulapo’ is a Yoruba word, usually translated as ‘he who carries death in his pouch’, chosen in preference to the British name Ransome, whose un-African sound had been irritating him for years. Although the name had been adopted voluntarily by his grandfather, an Anglican minister, Fela characteristically described it as a ‘slave name’. In fact one of Fela’s recent ancestors had been a slave. His mother Funmilayo, whose maiden name was Thomas, was the granddaughter of an Ilesha man captured and enslaved in childhood, who arrived in the Egba region around Abeokuta on foot from Freetown in Sierra Leone, where he had been released in 1834 following the British abolition of slavery.

Questions of identity appear self-evident, or anyway self-regulating, and therefore a distraction from serious matters, to people whose histories are, so to speak, their own: to the British, French, Americans or Chinese. But they loom large in the consciousness of those recently colonised, whose ancestors have been enslaved, whose countries have been delineated and named by foreigners. Renaming individuals, cities, perhaps a whole country, can be seen as psychologically liberating. French commentators in their shameless way have not hesitated to use words like ‘authenticity’ and ‘negritude’ about Fela.

Artists are suggestible by nature, naive, ‘child-like’, idealistic. How, otherwise, could they spend their lives trying, often vainly, to convey beautiful visions to other people instead of doing something more imme- diately bankable? Fela’s parents were distinguished professionals, both teachers, his father the Rev. I. O. Ransome-Kuti (who died when Fela was seventeen) an eminent headmaster, Funmilayo a ground-breaking feminist, fierce political activist and Lenin Peace Prize laureate, who was a friend of Ghana’s Nkrumah and had met Mao Tse-tung. They were well off and well known, and probably did not envisage a career as a popular musician for any of their children. The ferocious childhood discipline Fela recalled later may have had something to do with concentrating his mind on schoolwork. However, when he was nineteen his mother bowed to the inevitable and sent him to study music at a London institution. Spankings or no, he came from a prominent liberal and intellectual family, one that had a firm idea of service to the fellow citizen, of noblesse oblige.

Accounts of Fela as a young man show him as witty and energetic, with talents as a communicator, eager to organise bands and play music – jazz trumpet in the early days – not very successfully although with great application, but straitlaced and conventional: scared by horror films, afraid of getting girls pregnant (and perhaps of girls), not a drinker, persuaded by his elder brother that cannabis drives people mad. He married Remi Taylor, the mother of his three eldest children, in London and returned to Nigeria in 1963, working briefly for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation and starting his first real band the Koola Lobitos, which played jazz and the Ghanaian form ‘highlife’.

His mother urged him one day to play music his own people could understand, not jazz, and he began experimenting with new forms and instruments. He and Remi were soon living amicably apart, and in the mid-sixties he discovered, more or less simultaneously, cannabis and what one might call ‘girls in general’. Later, towards the end of the Nigerian civil war, the Koola Lobitos made a financially disastrous tour of the US. Fela stayed in Los Angeles for several months and was politicised there by a girl friend, the singer Sandra Smith, a member of the Black Panther Party, who persuaded him to be proud of Africa and recognise what had been done to it.

Returning to Nigeria in 1970, Fela relaunched the band in larger form under the name Africa 70. He had abandoned highlife and was playing a new kind of music, recognisably jazz-influenced, that he called Afro-Beat. The band in the early 1970s normally had around fourteen instrumentalists including four or five horns, four or five drummers and three guitarists with Fela singing, conducting and playing, at that time, electric keyboards (he had already given up trumpet but had not yet taken up the tenor sax which was usually present in the 1980s). Apart from maracas and minor percussion instruments, there was a variable number of girl backup singers. Up to four dancers at a time performed in the spotlit ‘cages’ that some visitors claimed to find offensive. From 1970, too, Fela began to pour out the stream of tunes and lyrics, all lasting at least a whole side of a twelve-inch LP, that continued until the late 1980s. A few are in Yoruba but most are in pidgin, the English-based lingua franca of the West African coast. It is a language that adapts easily to mockery, criticism and satire: the uses to which Fela consistently put it.

Satire, progressive and regressive

The eighty-odd published lyrics – there are said to be more in the production pipeline – constitute a meandering but structurally simple discourse whose details are sometimes obscure to non-Nigerians. The earliest is entitled Buy Africa (1970); the first big hit the Yoruba-language Jeun Ko’Ku (1971). The consistent themes attack injustice in various forms: racism on world and local levels, gross inequalities of income and opportunity, corruption, the threat of real force that subtends government in general and military government in particular. Minor themes attack pretentiousness and ill-judged imitation: the 1973 track Gentleman pokes fun at people who want to dress with suffocating formality – vest, tie, socks, three-piece suit – in the turkish-bath climate of Lagos; its hugely popular companion piece Lady, published the following year, rather ambivalently cites the demanding nature of ‘African woman’, liable to sit down and eat before men and even claim equality if given half a chance.

Gentleman is progressive and Lady, superficially at least, rather the opposite, despite a tone of grudging admiration for this stroppy woman. This is characteristic of Fela. He had no interest in perfect philosophic correctness which has a very limited role in show business. And in any case, what with one thing and another, contradictions of a sometimes painful sort were apparent in Fela’s own life and household. Some lyrics like Unknown Soldier (1979) and Coffin for Head of State (1981) are personal, but titles like Why Black Men Dey Suffer, Zombie, Alagbon Close, Expensive Shit, Sorrow, Tears and Blood, Dog Eat Dog, VIP, ITT and Beasts of No Nation are really a string of anarchist slogans directed against a system, and a series of regimes, that seemed to get steadily more venal and oppressive throughout his working life.

Fela’s political programme, to the extent that he had one, was perpetually under construction; his political judgement was usually hasty, often flawed, sometimes (for example his initial approval of Idi Amin’s antics on the ground that if the Western media were against the Ugandan despot he couldn’t be all bad) almost perverse; but his political prejudices – pro-African, pro-underdog, anti-pomp and anti-injustice – were generally sound. They are gut feelings shared by most Africans. When Fela spoke (as he often did) in the name of ‘Africa’, he may have been projecting some of the attitudes of a famous, eccentric, successful, westernised, upper-class Yoruba anarchist and bohemian on a largely uncomprehending continent; but people also understood that the Africa he referred to was a colonised Africa whose private history had been disrupted by outside forces and needed to be relaunched. This knack of being wrong, but right, endeared Fela to his constituents, but puzzled everyone and enraged powerful individuals implicitly criticised, at the same time providing them with ammunition.

Some obituarists have mentioned fiery political diatribes delivered from the stage of the Shrine. Few if any have pointed out that until quite recently these were often more like stand-up comedy routines than speeches. The audience reaction included a lot of laughter, often at familiar sallies. Laughter – by no means always harshly mocking – came easily to Fela, and an important part of his talent was the ability to make others laugh. It occurs to me that he may have felt secretly that this meant he was not serious (like his parents, like his doctor brothers), and that some such secret fear may have subtended his prolonged head-butting contest with the Nigerian authorities.

The Shrine audience was disproportionately middle class since the price of entry, modest by Lagos club standards, was increasingly beyond the means of most Lagosians. Of course other places offer good live music, some by internationally known bands, but only the Shrine could offer such an individual sound accompanied by jokes, verbal fireworks and (on the right night) some ‘traditional’ ceremonials, carried out at a run to distinguish it (Fela once told me) from the solemnity of ‘European religion’. It was an avant-garde place with a strange, somewhat feverish atmosphere and reputation. Respectable people, especially women, often claimed to be afraid to go there; even habitués drawn by the music could harbour exaggerated beliefs and anxieties about the club, its owner and his followers.

However, these avant-garde intellectual admirers, relatively few in number and ambivalent about Fela’s political and sociological attitudes, were not the musician’s real constituency. That was to be found among people who cannot afford to go to nightclubs, the overwhelming majority in Nigeria’s cities, especially in the Yoruba South-West. It should be understood that from a European viewpoint large African cities are sociologically in another time as well as another continent. Vertiginous disorderly physical expansion; impoverished and exploited populations of newly transplanted villagers (in Lagos’s case Yoruba in their majority but with many speakers of other tongues); stressful and unhealthy living conditions; the distortion, slow loss or outright abandonment of defining social traditions; corruption and economic chaos that appear never-ending: all these things recall nineteenth-century London or Edwardian New York (but without the triumphant capitalist expansion). However, recognisable forms of moral-religious and socialist-syndicalist dissent coexist with what might be called pre-Enlightenment comportments. The aspect most relevant here is an impassioned personalisation of social and political attitudes by populations who do not recognise, or do not trust, the institutional framework provided for their expression.

Street polemic

The loyalty of these groups, surely among the true wretched of the earth, is not won with a couple of hit records or a few well-turned phrases, although these can start the process. Lagos street people may not be scholarly but they have heard a lot of political promises and seen plenty of would-be demagogues. They have a keen ear for hypocrisy, a sharp eye for pretension, the habit of scrutinising candidates for their approval closely from all angles. They do not fetishise rationality – indeed rather the opposite – but require any discourse to be emotionally consistent with the candidate’s social behaviour.

Fela was already a favourite son of those potholed, rubbish-strewn, clamorous streets by the beginning of the 1970s, the passage of his battered Opel estate greeted by cries of his name or one of his self-awarded titles (Chief Priest! Black President!) from the anonymous passing crowd. It had been recognised that with Fela what you saw was what you got: insolent informality of dress and behaviour, open use of hemp (as in other countries illegal and set about with contradictory but strongly held beliefs), a large, socially and tribally disparate household and retinue, voracious sexual promiscuity not unlike that of some Western rock stars but justified with references to African polygamous tradition.

The growing list of titles, Fela’s musical brilliance, his near-genius as a bandleader and showman, seemed appropriate in the child of famous parents and particularly a famous mother, loved and (according to some) feared by the Egbas and other Yorubas for her formidable leadership of market women in opposition to the British and local authorities. Fela too, on stage and in interviews, was displaying a fearless eagerness to attack the government, not just for perceived incompetence, corruption, etc., but for illegitimacy: for having seized power by force, for assuming the right to rule without consulting the ruled or obtaining their voluntary acquiescence. Even under the Gowon regime – gentlemanly by more recent standards – this kind of polemic, which was not always deeply considered or carefully phrased, had a risky side that went straight to the heart of the street.

Over the years, as Nigeria’s oil boom faded and regimes succeeded one another, the list of these provocations grew. When secession was anathema after the defeat of Biafra, Fela said the Ibos had been right to secede and named his house the Kalakuta republic (Kalakuta after the name of a cell in which he had been detained briefly on a hemp charge). Under the Obasanjo regime he poured scorn on the government’s attempts to increase food pro- duction and refused to take part in Festac, a showpiece world African arts and culture festival mounted at great expense (and attended by financial scandals). In 1979 he married, in an improvised traditional ceremony, his current crop of twenty-seven girl singers and dancers. This was taken as an oblique criticism of prominent Nigerians who posed as modern, monogamous men but openly kept numerous mistresses by whom they had children. The hemp proselytising, the major and minor hit-or-miss polemics on current events, continued throughout.

So did Fela’s loyalty to his followers and his readiness, when asked, to help individuals in need or in trouble with the law. He could have become extremely rich by limiting the size of his household and concentrating on the commercial exploitation of his work (possibly the music itself, which is often roughly finished, might also have benefited). But the refusal to play the card of class exclusion, the decision instead to embrace the role of lumpen chieftain, made him a spendthrift: easy come easy go, there are a lot of us so better buy a bus as well as a Range Rover. His household usually ate but its members were often broke (only a few stole from him). Senior musicians in the band grumbled about their pay. Alarming quarrels often erupted among the dancing girls over missing earrings or stolen underwear.

Some of these attitudes may seem more justifiable than others, but taken as a whole they, and the trouble they caused, made Fela a hero. Regular attempts to prosecute him for hemp possession were bought off or fought off; a refusal to yield anyone who had sought his help to pursu- ers resulted in at least one attempted prosecution for abduction. In 1977, after a confused quarrel between a couple of Fela’s men and a traffic policeman, his house was attacked and burnt out by the local army regiment and many people, including Fela himself, his mother and younger brother, were beaten and injured. The land was later seized, without compensation, by the Lagos State government. In 1984, under the Buhari military regime, he was given a five-year sentence by a military tribunal for currency trafficking and served twenty months, being released some time after his elder brother Olikoye became health minister in the first Babangida government. The technical nature of the offence and the trivial sum involved (£1,600 sterling, a cash float for the band’s arrival in Los Angeles) made it absolutely clear that the prosecution was cynical and driven by the personal malice of someone highly placed in the Buhari regime.

After his release in 1986 Fela ‘divorced’ the twenty-seven wives, but did not send them away (of course some had already left). He continued to tour and play the Shrine, now in Ikeja near Lagos airport; the music continued to branch out in experimental directions, Fela now saying he wanted to write and play something equivalent to European classical music. In recent months, already unwell with the AIDS that killed him, he was quoted as giving some sort of verbal approval to the Abacha government: astonishing, were it not for his illness and the fact that his younger brother Beko, a GP and human rights activist, was in jail in Maiduguri, convicted by a military tribunal of involvement in an alleged coup plot.

Lagos, a town whose population is unreliably estimated at 8 to 10 million, turned out for Fela’s funeral procession on 20 August, seven choked hours from Tafawa Balewa Square on Lagos Island to Ikeja. Numerous civilian, military and police grandees attended, not all Yorubas and not gloating, but mourning a great musician and Nigerian original, an awk- ward cultural asset who will be terribly missed.

*

There is a tragic double coda: Fela’s niece Frances (‘Fran’) Kuboye (of whom he was very fond), the daughter of his elder sister Dolu, died of a heart attack the day after his funeral. She was a dentist – rare in Nigeria – who, with her husband Tunde Kuboye, ran a club called Jazz 38 in Ikoyi, the smart end of Lagos; he played bass and she sang in the house band. In the late 1980s Fela used to perform there once a week, playing tenor sax in the band Extended Family before rushing across town to the Shrine. Jazz 38 closed a couple of years ago when the lease expired, and money difficulties delayed the opening of its successor. Frances was forty-eight and leaves three children. Only a few weeks later, Fela’s third child and second daughter Sola died of cancer after a short illness. Sola was an energetic young woman said by some friends to resemble Fela closely.

Fela Anikulapo Kuti, 1938–1997

Frances Kuboye, née Ransome-Kuti, 1949–1997

Sola Anikulapo Kuti, 1963–1997

*

This article first appeared in the NLR 225, September 1997, and has been subsequently updated.

all photos (c) John Howe. Taken at the Shrine in Lagos, 1972