Fascism, Racial Capitalism, and Police Violence: Antifascist Reflections from the 1930s to the Black Panthers

Blackness and Black Lives Matter call attention to the ever-present potential of racial capitalism to turn fascist. This leads to an important lesson of Black Lives Matter and its response to the police: its abolitionist awareness that not only is the capitalist state an enemy of the people, but that it can and should be replaced.

Bill Mullen and Chris Vials are the editors of The US Antifascism Reader, now available as a free ebook here.

In 1935, a left-wing journalist named H.C. Engelbrecht reported on the use of a new and revolutionary method of crowd control called “tear gas.” Munitions manufacturers had learned to weaponize gas in very lethal ways during World War I, and it was an easy step to extend that technology to scatter demonstrators. Engelbrecht noted how tear gas was billed by its makers as a “humane” method of crowd dispersal, as opposed to the older method–employed from the United States, to Cuba, to British India–of simply mowing people down. “Tear and irritating gases have made the suppression of picketing and labor demonstrations a bit easier,” he wrote. “The old method of machine gun slaughter causes too much resentment and publicity, the new way avoids all this and is just as effective.”

But despite this supposedly more humanitarian method of restoring law and order, Engelbrecht and his generation had no problem tagging it with the harshest of labels: fascism. The police use of tear gas was the example of a military logic that was “frankly fascist in character,” he wrote. Moreover, his piece appeared in the magazine Fight!, the journal of the American League against War and Fascism, the largest antifascist coalition in the United States at the time. The tendency revealed by the state’s use of tear gas was quite clear to its readers.

Ever since the 1930s, the decade in which fascism first captured the imaginations and the fears of the U.S. public, the left in the United States has often described the use of force by the police, lethal or not, as “fascist.” A common cry at recent protests has been “No cops, no KKK, no Fascist USA!” But what does it mean to call the crack of a police baton “fascist”? Or, more dramatically, a racist pistol shot in the back?

To be clear, capitalist and authoritarian communist states have always used police violence, so fascist regimes have no monopoly on police brutality. In the United States, authorities have persistently used police and even military force to control demonstrations, especially against those organized by labor and people of color. And more to the heart of the issue driving the current crisis, authorities have used police violence to enforce the country’s various class and racial hierarchies, which also serve its capitalist political economy (though race, to be equally clear, has a logic of its own that is difficult for ruling elites to properly manage). Be that as it may, it’s not necessarily hyperbolic to talk about police violence as “fascist,” even in a country like the United States which doesn’t technically have a fascist regime (yet). To take a step back, we should keep in mind that fascism can manifest on a number of different levels. In short, fascism can be a state, a movement, or, more fundamentally, a mindset or rhetoric.

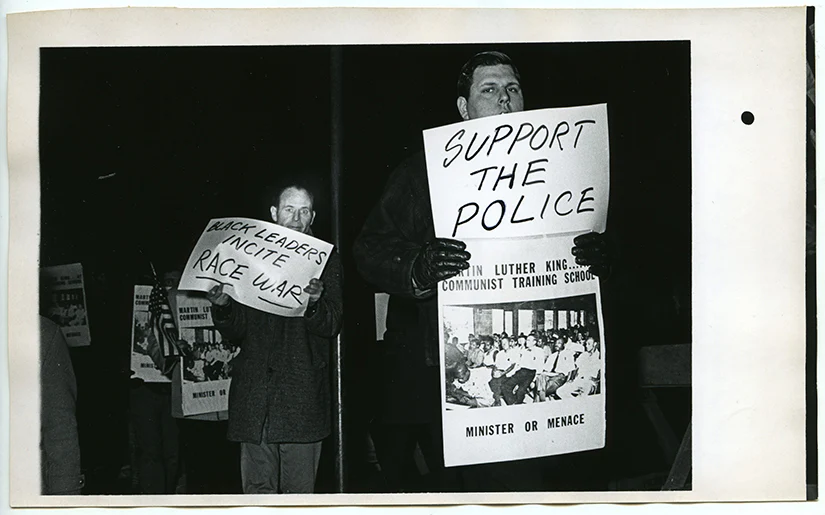

Historians of fascism tend to agree that there have been mercifully few fascist states: Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy are the two that everyone agrees on, and other scholars would add Imperial Japan and Franco’s Spain. But fascist movements have appeared in most countries around the world, before and after World War II, including the United States. Up to the present, fascism has confronted people in most countries as a set of far- right political mobilizations. As Oxford historian Roger Griffin wrote back in 1993, “as a political ideology capable of spawning new movements, fascism should be treated as a permanent feature of modern political culture.” In the United States, these fascist movements are typically driven by male violence (including militarism), racism, strict social hierarchies, and the desire to restore a mythical national past. They terrorize individuals and can create a toxic political environment even when they don’t fully take state power. Prominent examples have included the Ku Klux Klan, Father Coughlin’s “Christian Front” in the 1930s, the anti-civil rights backlash in the 1950s and 1960s that culminated in the George Wallace presidential campaign in 1968, influential elements of the Christian Right, and, more recently, Trumpian “white nationalism.” All of these movements impacted (or constituted) mainstream politics in their day. And all aimed to violently restore social hierarchies that were threatened by insurgent political power from below, including new immigrant voting blocs, antiracist movements, labor unions, socialist organizing, feminism, and gender nonconformity.

Finally, there is the more nebulous fascist “mindset,” dissected most elaborately in the influential socio-psychological study The Authoritarian Personality in 1950, funded by the American Jewish Committee. This mindset manifests in politics as an equally nebulous rhetoric, one fleshed out most recently by Jason Stanley in How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us vs. Them. As we wrote in The US Antifascism Reader, fascist words set aside a standard Enlightenment political vocabulary of freedom and liberty in favor of a lexicon of power, action, violence, and race. Critically, there is also a cyclical narrative of national apocalypse followed by a bloody, redemptive rise from the ashes. Fascist words and fascist personalities can exist independently of organized fascist movements, though never in a cultural vacuum. They signal an amenability to fascism that can easily be sharpened into more potent, organized forms.

So where do the police enter this mix? In short, on a number of possible levels.

First and most literally, there has been a persistent overlap in personnel between the police and fascist movements. In other words, some cops have also been closet or even open members of fascist organizations. The cross-over between the Ku Klux Klan and local police was well-known; antifascists in the 1930s railed against the presence of anti-Semitic Christian Front members in the ranks of the NYPD and Boston Police, and cops today have also been spotted with alt-right tattoos. This is no coincidence. If your motivation to be a cop is fueled by a need for adventure and social power, and not public service – as is so frequently the case – then your desires are bound up with action, risk, law and order, uniformed violence (particularly against working class people of color), and being an all-around tough guy. All of these things fit quite comfortably in the libido of fascist politics.

In the United States, there is also the crucial historical role of policing – whether in uniform or not – in enforcing color lines, which makes it quite easy to enter the police on the white supremacist terrain central to fascist politics in the West. As important, the long historical connection between policing and “race-making” in the United States (to use a term from scholar Nikhil Singh) helps to explain why the police remain to this day a fetishized ideal within white nationalist politics. Scholars in African American Studies and Critical Race Studies have consistently shown how policing in North America emerged from slavery and the slave patrols. The slave patrols were an avenue for the white working class to assert themselves, gaining a relative degree of power and sense of worth within a class hierarchy that otherwise devalued them.

This “perk” helps to explain why the police as an institution is close to the very soul of modern white nationalists, an institution worth killing or dying for. It is why Trump and his base cannot say enough about the glory of the police – even encouraging police violence, especially against “criminal” immigrants. To “Abolish the Police” is to remove the citizenry’s frontline defenders and leave the (white) body politic naked to the degradations of black and brown crime – crime that would inevitably flood their lighter-skinned neighborhoods. As Theodor Adorno and his co-authors of The Authoritarian Personality wrote long ago, the fascist mind simply cannot wrap its head around “equality” and sees any movement for social leveling (e.g., Black Lives Matter or mere police reform) as a conspiracy to simply flip the tables and dominate the former masters. The egalitarian world imagined by the slogan “Abolish the Police” is simply the equality of a world not worth living in. Coupled with the far-right’s self-image as gun-owning citizens’ militias, the one-two punch of “Abolish the Police” and gun control pushed by the left would, in their minds, leave them without the most sturdy pillar of their identity: the weaponized masculinity that they have chosen as their ego’s foundation amidst a highly alienating neoliberal political economy.

A third important element of police fascism is their role as what Lenin called “armed bodies of men” who protect the state and private property. Here the link between race and class, or more specifically between whiteness as property, as scholar Cheryl Harris has put it, is critical. In his searing 1966 essay “A Report From Occupied Territory,” James Baldwin rendered this nexus starkly:

Now, what I have said about Harlem is true of Chicago, Detroit, Washington, Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and San Francisco—is true of every Northern city with a large Negro population. And the police are simply the hired enemies of this population. They are present to keep the Negro in his place and to protect white business interests, and they have no other function...This is why those pious calls to “respect the law,” always to be heard from prominent citizens each time the ghetto explodes, are so obscene. The law is meant to be my servant and not my master, still less my torturer and my murderer. To respect the law, in the context in which the American Negro finds himself, is simply to surrender his self-respect.

If Stuart Hall is correct that “race is the modality through which class is lived,” then under capitalism the police are the apparatus for generating that phenomenon – and Black consciousness of it – quite forcefully.

This leads to the final link between police and fascism: that is, increasing police violence against people of color can also be a symptom of a bourgeois state sliding into a fascist one. Within the U.S. antifascist tradition, the Black Panthers offered the best and clearest articulation of this view. It is often forgotten that in 1969 and 1970, they widely organized under the banner of “antifascism” and founded National Committees to Combat Fascism all over the United States (effectively, these were local branches of the Black Panther Party). The hosted a “United Front against Fascism” conference in 1969 to unite Black, Latinx, Asian American, and white radicals in a coalition against a rising tide of reaction. The context was the election of Richard Nixon, the persistent assassination of Black leaders, the rise of George Wallace and the “southern strategy,” and, most broadly, a mood shift within the white majority and its attitude toward dealing with social unrest: namely, its turn away from Great Society reform in favor of the iron fist of “law and order.”

Kathleen Cleaver articulated a recurrent Black Panther analysis of fascism and police violence in a piece she wrote for The Black Panther newspaper in September 1968 called “Racism, Fascism, and Political Murder.” One passage bears quoting at length:

The advent of fascism in the United States is most clearly visible in the suppression of the black liberation struggle in the nationwide political imprisonment and assassination of black leaders, coupled with the concentration of massive police power in the ghettos of the black community across the country. The police departments nation-wide are preparing for armed struggle with the black community and are being directed and coordinated nationally with the US Army and the underground vigilante racist groups for a massive onslaught against black people. But, the billy clubs and mass arrests and guns are no longer just for black people; the white peace movement and the student power struggle are also beginning to get a taste of police violence.

A number of themes emerge here that recurred in Black Panther writing about fascism and the police. First is the idea that the United States is not yet a fascist state, but that it is trending in that direction. Second, the advance of fascism manifests itself in the daily lives of people of color and their allies as a toxic admixture of increased police violence, the domestic use of military force, and the encouragement (even tacit employment) of white vigilante violence. In the context of the 1960s, the state used this admixture quite effectively to neutralize black leadership, either through imprisonment or assassination.

Finally, we see here a recurrent idea in Black antifascism dating to the 1930s. That is, Cleaver’s observation that police violence was also starting to envelop white peace movements reflects the view of fascism as a widening circle of terror. As Cleaver wrote in the final lines of her piece, “Black people have always been subjected to a police state and have moved to organize against it, but the structure is now moving to encompass the entire country.” With this statement, she did not mean that fascism merely extends the police state to whites and creates an equality of terror. Rather, fascism, in this analysis, means a universal loss of democratic rights for all, but also an intensification of terror for the traditionally ghettoized, even to the point of genocide.

Blackness and Black Lives Matter, in this formulation, call attention to the ever-present potential of racial capitalism to turn fascist. This leads to a final, important lesson of Black Lives Matter and its response to the police: its abolitionist awareness that not only is the capitalist state an enemy of the people, but that it can and should be replaced.

1. H.C. Engelbrecht, “Peace with Tear Gas,” Fight, February 1935, 8.

2. Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism (London: Routledge, 1993), xii.

3. Nikhil Pal Singh, Race and America’s Long War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018)

4. See for example, Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010).