Protest is as Essential as Hand Washing

"We have two ongoing epidemics. One has been with us for only a few months; the other is over 400 years old." Joseph Godfrey on Covid-19 and protesting while Black.

Anyone who has ever engaged in a large-scale protest like I have knows that there is always a level of risk. Try as you might, but you can never completely control the actions and outcomes of a protest. Mixing enraged and grief-stricken protestors who have had enough, as we’re seeing across America and the world, with excessive force-loving cops can be a recipe for disaster.

Protesting while Black amplifies the risk, as it seems to invite all kinds of excessive force, regardless of the manner of protest. Whether—as we’ve seen over the last two weeks in the United States—police fire rubber bullets and tear gas at protestors, plow their vehicles into crowds, slam activists to the ground, or tase protestors in their cars, the cops make it clear what they think of us and our protesting—of our so-called constitutional right. But this should come as no surprise to anyone who has seen photographs or videos from the Civil Rights Movement of police officers beating protestors over the head with their batons and unleashing their dogs on men, women, and children. What are we to expect of officers who come rolling in on tanks and are dressed in tactical military gear? Of officers who almost never receive any sort of punishment for engaging in excessive force? As Harvard historian Dr. Khalil Gibran Muhammad and CUNY professor Alex S. Vitale document in their books, The Condemnation of Blackness, and The End of Policing, respectively, the criminalization and policing of Blackness in the United States has been ongoing over the last 400 years. Policing as a profession traces its origins to slave patrols, when groups of elected officials and other white men deputized by the plantation-owning class patrolled slave states to reinforce the violent system that kept slavery alive. When the weight of history is taken into account, these aggressive tactics toward Black people should not surprise us. But protesting during a pandemic brings an added level of precarity to the situation.

As things currently stand, the number of people worldwide infected by the novel coronavirus is 7,164,892. The global number of those dead from Covid-19 is 407,319. In the United States, the numbers are 2,022,156 and 112,954, respectively. And given the way that the virus spreads—from person to person through respiratory droplets, this makes protesting all the more dangerous. Just consider the way singing, a form of amplified sound, was able to spread the virus among 52 people at choir practice in Mount Vernon, Washington. Or the fact that asymptomatic carriers seem to play a considerable role in transmission.

Because of this, there are some who worry that the large protests taking place in response to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people killed by the police will result in additional outbreaks of the deadly coronavirus. In two weeks’ time, they say, we may very well see a second round of a viral wave that significantly changes the reopening plans of cities and states. Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a top White House adviser on the pandemic said this, on the risk of protests spreading the virus:

I get very concerned, as do my colleagues in public health, when they see these kinds of crowds. There certainly is a risk. I can say that with confidence.

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms (D-GA) whose city has seen large scale protests also spoke of the concern of further transmission on CNN’s “State of the Union.” This is what she had to say:

Around 11:30 last night, I realized that I hadn’t looked at our coronavirus numbers in two days. And that’s frightening, because it’s a pandemic, and people of color are getting hit harder. I am extremely concerned when we are seeing mass gatherings.

Mayor Bottoms is right in her point that the novel coronavirus has and is continuing to kill a large and disproportionately high number of people of color in this country. And given the scores of Black people and other people of color we’ve seen marching in the streets, it seems safe to assume that protesters congregating in tightly packed spaces, shouting, and sharing protest materials with each other will likely result in more people, many of whom will likely be Black, getting sick and dying of Covid-19, no matter how hard protesters work to maintain safe practices and minimize spreading.

And yet what is missed in the Atlanta mayor’s remarks and the remarks of Dr. Fauci, among others, is what is to blame for the high death rates in Black and Latinx communities from the coronavirus—and the relationship between susceptibility to Covid-19 and the murders of innocent Black people by cops. Here, both Mayor Bottoms and Dr. Fauci have missed a vital opportunity to highlight the way white supremacy and capitalism are to blame for both the racial disparities we’re seeing during this pandemic and the long-term epidemic of police murdering innocent Black people.

After all, is it not the same government that authorizes and allows cops like Officer Derek Chauvin to kill people like George Floyd that has continuously failed to address the systemic issues that keep Black people and Latinx people in “essential” low-wage jobs that expose them to the virus? Is it not the same government that has for generations failed to address the health disparities that ravage Black, Latinx, and Native communities in this country that continues to give police departments excess military equipment through the 1033 Program? These issues may seem to be unrelated, but this is about more than just overlapping acts of discrimination and white supremacy. This is about racial capitalism.

As the late Cedric Robinson, former professor emeritus of political science and black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara documented in his work, racism is central to the logic of capitalism. Capitalism is dependent upon antiblackness, genocide, and imperialism. It is not by mistake that Black people in the U.S. have higher rates of heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and now Covid-19 deaths, than other groups—but by design. Because of the nature of racial capitalism, police violence is not a deviation from proper policing procedures, but as Steve Martinot and Jared Sexton argue in their article “The Avant-garde of White Supremacy,” “the relationship between police violence and the social institution of policing is structural, rather than incidental or contingent.” To not speak of the interconnections is striking, and it is dangerous because it allows the system—the very system that killed George Floyd, whose body, it’s worth mentioning, contained coronavirus antibodies, a sign that he like so many other Black people had been infected by the virus—to continue to perpetuate itself, largely unexamined.

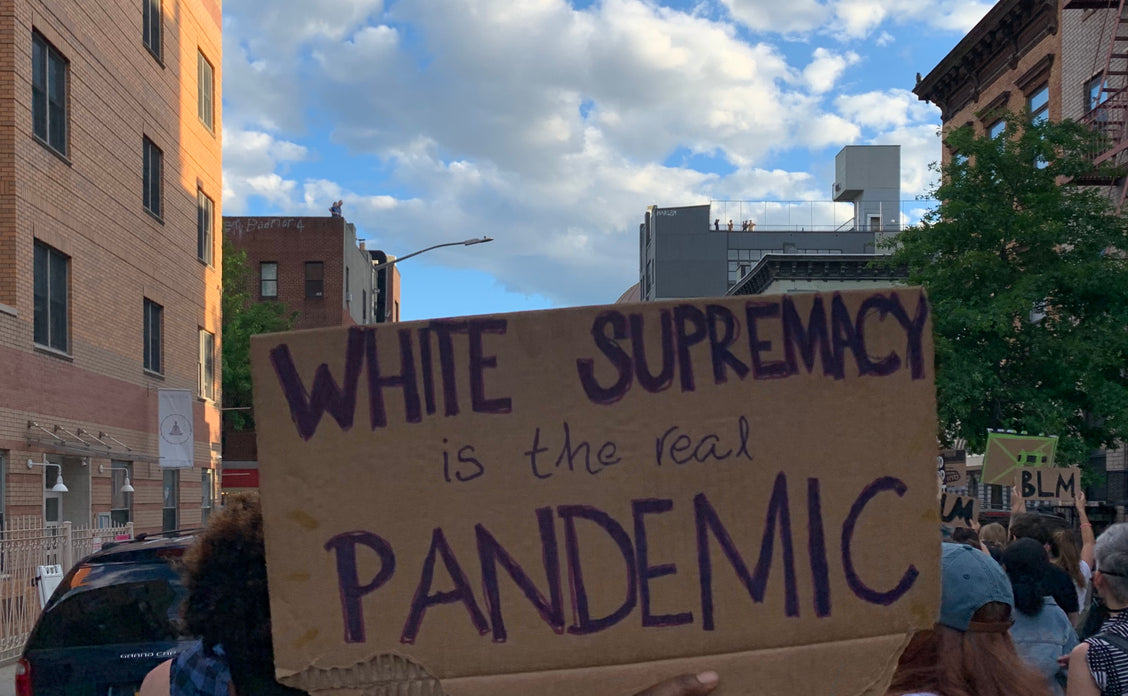

But where some elected officials and bureaucrats have failed to make this connection, doctors, nurses, and EMTs have not. Health care workers have championed protestors from sidewalks and windows, as well as joining and calling their own protests, often in scrubs and lab coats, and have been some of the most vocal about the relatedness of the two issues. As expressed in a sign I saw held up by a healthcare worker that read “RACISM IS A PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY,” we have two ongoing epidemics. One has been with us for only a few months; the other is over 400 years old.

And so while neither the remarks of Mayor Bottoms or Dr. Fauci, or others like theirs are outright condemnatory, and both individuals may very well sympathize with the protests taking place, there seems to be an implicit condemnation, a failure to realize that these protests are just as essential as proper hand washing. Just as antiblackness has not stopped in response to the global spread of the novel coronavirus, neither can our response to it stop. Even if our response to anti-Black violence increases the spread of the virus. Which means we must do in this moment what Black people protesting the unfair and violent conditions we face have always done—consider all the risks, the risks of doing and not doing—and then respond in the most effective and life-affirming manner possible. But going back inside, so long as Black people continue to face gratuitous violence and lynching by the cops, is not an option. Coronavirus or not.

And so, if there are additional outbreaks of the virus that result in the deaths of others, protestors and non-protestors alike, it will not be the fault of those taking to the street to say enough is enough. Condemnation belongs to the United States government that made these protests necessary in the first place. That made protestors decide after months of arduous lockdown measures to risk their lives, in numerous ways, to protest the ongoing lynchings taking place in this country.

It goes without saying that a potential new outbreak of the virus is tragic. But it is even more tragic and enraging when you consider that like the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many other Black people in this country across the centuries could have simply not have happened. If only this country would decide to finally address the most insidious virus, the white supremacy that surges through its veins.

Joseph Godfrey is a writer and graduate student studying and living in New York City.