The Winter Slaughter

This fall marks the 70th anniversary of a brutal and largely unknown massacre of the early cold war on the Korean island of Cheju/Jeju. In this article, Brendan Wright recounts the history of the massacre, placing it in the context of Cold War politics and the history of the Korean peninsula.

This fall marks the 70th anniversary of a brutal and largely unknown massacre of the early cold war. Between November 1948 and April 1949, South Korean government counter-insurgency forces launched what US observers at the time referred to as a “program of mass slaughter” against the population of Cheju Island. The bloodletting was thorough, sustained, and calculated. Anywhere between 10 and 20 percent of the island’s 300,000 population was wiped out from the onslaught. Thousands more were driven into exile in Japan.

For decades, this history remained repressed by the nation’s military regimes and distorted by anti-communist ideology. Labelled a “riot” at the time by the central government, the violence on Cheju was blamed on leftist agitators and their alleged backers in the Soviet Union. However, over the past three decades, the people of Cheju have claimed collective ownership and representation of their traumatic past—a difficult and all-too-rare feat in human history. The once-charred island landscape now exists as a living requiem for the spirits of the afflicted and their still-largely untold stories, while the clandestine truths that the islanders maintained between communities now help form the core identity of the island’s population. Word of the once-buried massacre is now spreading beyond the island. Buses guide visitors on “dark tours” throughout the island, as the afterlife of this terrible history now uneasily comingles with the island’s bustling tourist industry. However, if considerable light has been shed upon the nature of the atrocities, the historical meaning of what is called the “4.3 Incident” remains contested and obscured.

Counter-Revolution and the Origins of 4.3

The so-called “4.3 Incident” draws its namesake from April 3, 1948, the date when local leftists launched a poorly armed uprising against police and right-wing paramilitary groups on the island. But the roots of the tragedy preceded the guerilla uprisings and reveal much about the nation’s tragic division. On August 15, 1945, the Japanese surrendered to Allied forces. American and Soviet officials had agreed to temporarily divide the peninsula into joint military occupations. However, Soviet troops did not reach the northern capital of Pyŏngyang until August 24, while American forces did not arrive in Seoul until September 8. This meant that the Japanese surrender left a power vacuum throughout the peninsula. Korean independence activists formed local governing councils called “People’s Committees” to maintain order and prepare for independent government. The ideological composition of these committees varied, but in general their membership and goals aligned with a politics of democratic socialism. Land reform, punishment for collaborators, mass education, and a unified nation-state dominated the agenda.

It is impossible to know what would have become of these early attempts at autonomous governance, as the cold war imperial powers had other designs. In the North, the Soviet Union absorbed the People Committees into its authoritarian socialist bureaucracy and lined their leadership with people deemed amicable to Soviet designs. In the South, the United States Army Military Government of Korea headed by John R Hodge formed an alliance with landlords, ex-collaborators, police, and rightist politicians to dismantle the People’s Committees. It was a recipe for civil war.

Cheju was under the authority of the American occupation government. However, its peripheral status, both geographically and politically, meant that it was largely ignored by American officials for the first year of the occupation. The result was that the island had a larger gestation period for independent rule under the control of a local People’s Committee. The island committee pursued moderate policies focusing on land reform, order, and preventing ex-collaborators from attaining positions of power, and gained broad support from the island’s population. Through this, an independent left acquired a strong foot-hold while rightists were consistently frustrated in their effort to gain influence and support. However, the fortunes of each group began to reverse in the fall of 1946, when Cheju was incorporated as a separate province of South Korea, leading to an increase in rightist administrators and the number of police on the island and the forced dismantling of the People’s Committee. Uprising in the fall of 1946 that took place on the Korean mainland also proved a boon to rightists throughout the country—including Cheju. These uprisings were blamed on communists, which hardened American officials’ anti-left stance and put the left on the defensive.

Tensions first came to boil on the island on March 1, 1947 in downtown Cheju city when 20,000 islanders held demonstrations opposing increased taxation, police brutality, rice shortages, and the destruction of the People’s Committee. Police fired on the unarmed protestors, killing six and wounding 8. In the aftermath, radical forces from the right and left sought to exploit the growing tensions on the island. Buoyed by mainland and US support, the right took the initiative, exploiting the crisis on Cheju to buttress its consolidation of the island’s repressive and administrative structures of government. By May of 1948, politicians from the hard-right sat at the helm of the Governorship, the police force, and the constabulary, and enjoyed the full blessing of US officials.

This ascent to power was coupled with a sustained campaign of dehumanization against the islanders. Political expediency, cold war paranoia, and mainland bigotry fused together to produce a toxic environment in which the entire population was painted as “red” deviants, while ominous threats of mass extermination began to circulate from the upper echelons of power. Cho Pyŏng-ok, head of the national police, stated that Cheju was full of people with “rebellious ideas” and warned striking employees that he would wipe out the island's population "if they got in the way of the foundation of the Korean nation". Not to be outdone, Deputy Head of Police Ch'oe Kyŏng-jin remarked that Cheju was an "island full of reds", with 90% of the population "tinged with left-wing ideology". Another senior official said it was “fine if 300,000 Cheju people were victimized” if it meant preserving order. Cho used his position to purge local moderates in the police force in favour of rightists from the mainland. Meanwhile, extreme right-wing paramilitary youth groups composed of disgruntled North Korean migrants began to flood the island, rampaging villages and torturing suspected leftists. While these groups were hated by the islanders, the police turned a blind eye towards their tactics and began to integrate them into their forces.

An Uprising and a Subsequent Slaughter

By the spring of 1948, Cheju’s political left was badly mauled, if not crippled. Most senior leaders had been arrested, assassinated, or were in hiding. Meanwhile, thousands of islanders languished in overcrowded jails where they underwent extreme beatings, wire torture, and countless other indignities. The US/Republic of Korea decision to hold separate elections throughout South Korea threatened to further consolidate this order. Badly cornered, on April 3, 1948, 350 guerillas from the island branch of the South Korean Workers’ Party (SKWP) launched coordinated attacks against police and right-wing youth stations in night-time raids. Historians debate the logic behind the uprisings, but the most persuasive evidence suggests that it was an ill-fated defensive maneuver, devised to strengthen the negotiating position of the SKWP. Despite their inferiority in numbers, the guerrillas initially scored a string of successes throughout the spring and summer and were able to disrupt the elections. The ideological leanings and political sympathies of the majority of the island’s population remains an open question. However, it is clear that the hatred of the security forces, coupled with genuine support for elements of the left’s program, allowed the guerrillas to flourish in these early months.

On August 15, 1948, the Republic of Korea came into existence. Its president, Syngman Rhee, saw the Cheju uprising as a test for the regime’s credibility as an anti-communist bulwark in the American orbit. On October 11, the now three-month-old South Korean government proposed a heightened campaign of suppression. Six days later, a naval blockade enveloped Cheju's coast, sealing off the island. The head of the Cheju constabulary, Song Yo-ch'an, announced that anyone found more than five kilometers from the shoreline would be shot, creating a free-fire zone throughout much of the island. Mainland rightists were offered land and employment if they killed leftists and were granted the power of summary execution. The seeds had been sown to cultivate a brutal civilian slaughter.

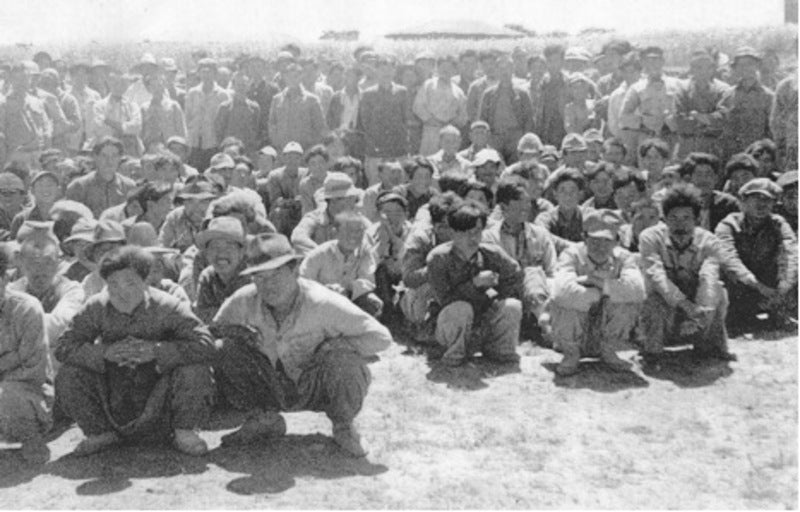

While the 4.3 Incident draws its namesake from the leftist uprisings of the spring, it is the winter slaughter that gives it its substance and ultimate verdict. Over this period, tens of thousands were killed—the majority at the hands of government forces. In military terms, it was a rout. The combined strength of the poorly armed guerrillas never exceeded 500. Photographic evidence reveals that the typical captured “guerrilla” was often a barefooted peasant, armed with a bamboo spear. Statistics hardly do justice to the mendacity of the American-backed forces, nor to the suffering imposed on the civilian population. Marauding gangs of rightist youth roamed from village to village, terrorizing the island’s agrarian and mostly unarmed population. The principal targets, young men suspected of leftism, were routinely dragged from their homes, tortured, and executed. Women were raped, the elderly parents of “rebels” were murdered, and the infants of alleged “leftists” were mutilated. The majority of the island’s forests were burnt down, livestock was slaughtered, and food was confiscated. The bodies of the dead were unceremoniously dumped in large piles and burned, while families were prevented from burying or mourning their loved ones. The word “indiscriminate” is at once both obligatory and misleading, for the pattern of village massacres reveals a political genocide implemented along the lines of class and ideology. Typically, counter-insurgency forced divided communities between landowners, families of police, and rightists on one side, and peasants and leftists on the other—massacring the latter and coercing the former into identifying “reds”.

Yet even with the slaughter, from the point of view of power and political order, the operation was seen as overwhelmingly successful. By April 1949, the rebellion was deemed effectively squashed, with over 2,000 “guerrillas” captured and 5,409 surrendering as part of an amnesty program, though it is likely that the majority of these men were unarmed peasants seeking shelter from the ongoing onslaught. Right-wing power on the island was meanwhile entrenched in the new political order. Members of youth groups received key positions in government and Cheju's economy, and held a virtual monopoly over its newspapers. Their fallen ideological brethren were honoured as patriotic martyrs in the struggle against communism, while Song Yo-ch'an, architect of the island's quarantine, became head of the country's military police. The Americans also shared in the spoils of victory, as an orderly election was carried out on the island in the spring of 1949. In this instance, the ruthless violence obligatory to the construction of a sprawling liberal empire was delegated to a client regime and sanitized by the spectacle of a free election. US ambassador John Muccio praised the counter-insurgency forces for blunting the power of a clear "Soviet effort to sow confusion and terror in southern Korea". Everett Drumright, Consular to the American Mission, noted the "gratifying progress" that was made in the suppression campaign and, without irony, attributed its success to the "good will and cooperation" between the islanders and the security forces.

Yet, the Cheju bloodbath was merely a prelude to a much greater slaughter of real and imagined leftists throughout mainland South Korea, as the whole peninsula became engulfed in a civil war that was textured and intensified by the cold war powers’ proxy war. At the height of the civil war years (1948-1953), a minimum of 100,000 unarmed “leftists” are estimated to have been killed by South Korean government forces. In world history, the Korean War is often presented as a stalemate. But the verdict is both narrow and misleading. In 1945, democratic socialists were the most well-organized and perhaps the most popular force throughout the peninsula. By 1953, the movement was all but obliterated in both halves of the country—absorbed and deformed in the North, vanquished in the South. Along with the thousands of lives lost in this campaign of political genocide was a certain idea of Korean nationhood that was stamped out by the cynicism and expediencies of the cold war. Coercive force, perhaps the key determinant in power throughout history, legislated the grim fates of the island’s population and its budding experiment with socialism and self-government. It is a bitter lesson, but one whose memory is worth preserving as Koreans navigate this strange moment in contemporary peninsular history that fills us with so much dread and hope.

Brendan Wright is a Korean Foundation Post-doctoral researcher at the University of Toronto