Reading the Revolution: A Memoir of 1968

"Our reading in 1968 and thereabouts, done in the context of mass movements of social protest, helped to transform us into revolutionaries."

For years I have thought of myself as a member of the “generation of 1968.” It was the year that I turned 23 and became active in “the movement,” as we called it then. Today, we naturally and quite rightly remember 1968 for the protests, strikes, and uprisings that took place in the United States, France, Czechosloviaka, and Mexico, as well as for the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. I and my friends and comrades were activists in the civil rights and anti-war movements as our women friends also founded the modern feminist movement. Yet, we may forget that this was also a time when — in the midst of protests and teargas, and sometimes gunshots and burning inner cities — we plunged into books. We were revolutionary readers, readers of the revolution.

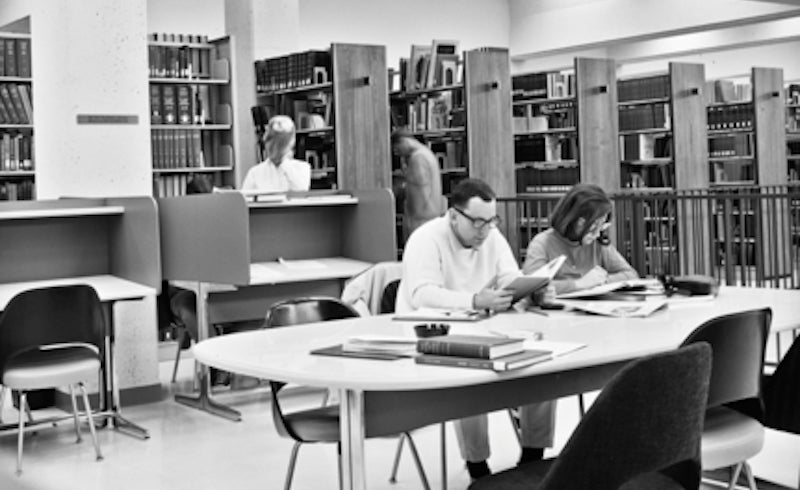

We not only tried to make the revolution, we also attempted read it, to understand what revolution had meant and what it might come to mean. We did so alone or sometimes in college classrooms but mostly in the hundreds or perhaps thousands of study groups that proliferated throughout the country. Some of the study groups grew directly out of the movements, as people tried to figure out what was going on with the fight for black people’s civil rights in the South or what was happening with the war in Vietnam. Black and Latinx activist organizations often had their own study circles, though mixed race study groups also existed. We sometimes simply started reading things — newspapers, pamphlets, books — and shared them to discuss together. Some of the groups were started by leftist political parties: the Communist Party, the Socialist Party, and later the Trotskyist or the Maoist organizations. The women’s movement created thousands of them as part of their “consciousness raising groups.” We were all of us young radicals, a new “people of the book,” and the book was often Capital, What is To Be Done?, or perhaps The Little Red Book.

A Family of Readers

Everyone who entered into the great reading revolution of 1968, of course, came to it from different places. There were a good number of “red diaper babies” in the universities, especially on the East Coast and in Chicago and Los Angeles; others came from elite families, but also from the middle class and from the non-Communist working class as well. Like everyone’s, my experience was unique. The La Botzes were a working class family of readers. My grandfather John Cornelius La Botz, a Dutch immigrant and a baker, had bookshelves lined with the works of Voltaire, Balzac, and Tolstoy. He was a socialist pacifist and an admirer of Norman Thomas, Bertrand Russell, and Mahatma Gandhi. As a child I heard their names and something of their ideas. By the time I was ten I had assumed that pacifist and socialist identity and took pride in it even before I fully understood it or had made it my own. It was our family’s identity and so it became mine.

I emerged from childhood with the notion that our family formed part of a church invisible of those committed to peace and socialism. Grandpa’s notions of socialism became clearer as I got older. When I was a teenager my grandfather pointed to the Soviet Union as a model of a socialist economy but a poor example of a democratic society. He also sometimes mentioned Sweden and later gave me a copy of Marquis Childs’ Sweden: The Middle Way. Once, when I was perhaps 15 or 16 years old, he whispered in Dutch that, Dit is te ruw voor moeder, that is “Too rough for mother” (my grandmother), and he led me out into the backyard where, sitting under the huge oak there, burned black from lightening strikes, he told me that Lenin — a name that until then I had never heard — said we should make the revolution with as little bloodshed as possible. All of this made it easier in my young adulthood to join the movement and the great reading revolution of 1968.

My mother Betty, the Irish side of my family, fed up with my father Herb’s philandering — he had gone too far and gotten deeply involved with another woman — left him on July 4, 1956. “It’s Independence Day,” she said. Independence Day and she was going to have hers. She, my sister Janet, and I took the train from Chicago to California. We settled in San Diego’s South Bay, on the Mexican border. We fell into poverty for a couple of years as my mother worked low-paid and part-time jobs to support her two children. What did I read then in 1956 and 1957? My grandfather wrote me long letters, ten pages sometimes, in his wonderful hand, about the evils of the Catholic Church and the Rockefellers, the militarists and the munitions makers. A neighbor lady, whose son was courting my mother, gave me a box of old books that included a set of encyclopedias published in the early 1940s and I read about the outbreak of World War II, before the authors knew who had won. I suppose because of the influence of my grandfather I read the articles on Fascism and Communism with particular interest.

My mother found work as a grocery clerk and within a couple of years married a U.S. Navy veteran, a conservative, who worked alternately as a commercial fisherman and a housepainter. Like my mother he had not finished high school and neither of them were readers. The only two publications that came into our house in those years were the Readers’ Digest to which he subscribed and my mother’s union newspaper, The Retail Clerk. I read the former and scanned the latter. The only books in the house were mine, mostly secondhand books of poetry: William Blake, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, W.H. Auden, and Ezra Pound.

My political reading began when my father, Herb, bought me subscription to Liberation magazine. Why Liberation? Well, he had been a conscientious objector during World War II and had been interned in a camp in Big Flats, New York, where my mother had lived nearby and where I was conceived. So too my uncle Bert, who at the end of the war, when the conscientious objectors were not immediately released from the camps, had joined a national rebellion of the country’s 12,000 COs called “End Slave Labor in America,” had gone on strike, walked out of the camp and consequently been imprisoned. The leaders and organizers of that movement had been associated with Dwight McDonald and his Politics magazine, and with the War Resisters League. Liberation, edited by David Dellinger, Bayard Rustin, Sidney Lens, Roy Finch, and A. J. Muste — socialists and pacifists — had that kind of radical politics.

I read it regularly and through its pages I followed the Cuban Revolution of 1959. I became a supporter of the revolution in its first few years (though I later became more critical of Castro’s Communist government and its assimilation to the Soviet Communist camp). While still in high school, reading Liberation led me to spend my lunch money on a copy of C. Wright Mills’ Listen Yankee! The Revolution in Cuba, then available in a small format paperback on magazine racks in the drugstores and grocery stores. Reading that book was my first experience trying to understand contemporary international developments.

In the evening in the early 1960s my mother and I watched the news together, appalled by the police violence against the activists of the civil rights movement, many of them children: beaten with clubs, attacked by police dogs, blasted and tumbled by water cannons. Though my mother had come for a Chicago Irish working class family whose racism rivaled and perhaps surpassed that of the southerners, she for some reason had no racist feelings. Once, when we lived in Chicago, she had rescued a black boy of nine or ten who had accidentally come down our block on his bike. The Irish women on their porches showered the boy with broomsticks and pop bottles. My mom walked him off the block and to safety. Now in the early sixties watching the TV screen she would ask, “How can they treat those poor people like that?” When one day I saw on the grocery store paperback bookrack Martin Luther King’s Why We Can’t Wait, I bought it, read it, and agreed with it. That was in 1963, the year I graduated from high school. I supported King and his followers, people in my family’s pacifist tradition, even if still only passively, only in my heart.

Reading Before 1968 — Kerouac and Ginsberg

A teacher at my high school, Leroy Wright, heard from another teacher that I liked to write, and so he stopped me one day at school to ask about my poetry. We began to talk regularly and he even invited me to stop by his house and so I became friends with him and his wife Karen. Leroy, who had served in the U.S. Marines, seemed to have adopted Ernest Hemmingway as both his literary ideal and life model. Leroy and Karen were childless hedonists. For Leroy, life was primarily a sensuous experience: fish to be caught, animals to be shot, novels to be read, music to be listened to, art to be viewed, and, perhaps above all, women to be slept with. He suggested to me that sexual conquest represented a man’s constant preoccupation and life’s greatest pleasure. Leroy’s mantra was Hemmingway’s slogan, “Good is what you feel good after.” Unlike Hemmingway, Leroy had no left-wing sympathies, being also an admirer of the quirky and pessimistic journalist H.L. Mencken. Leroy directed my American literature reading into the classics of the 1930s generation: Hemmingway, John Steinbeck, and William Falkner. And I read the trenchant and sardonic Mencken too.

While still in high school in the early 1960s, my friends and I met a woman, Di Christiansen, a Beatnik who had come to live in our small town of Imperial Beach, located on the U.S.-Mexican border. She had once moved in Communist circles, was a friend of folksinger Barbara Dane, and knew people in the Bay Area theater world who had worked for the United Farm Workers’ El Teatro Campesino. We learned from her about post-impressionist painting, about jazz music, and she later brought us to some very early anti-war demonstrations in the mid-1960s. She introduced me and my friends to other publications, such as Jack Green’s Newspaper, which published excerpts from books by Henry Miller and other authors who had been banned from the US mail. Di loved the Beat poets — Alan Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and their forbearer Kenneth Rexroth — and introduced us to them. Once at her house, she had us do a reading of Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi, in which I played the role of and carried a sign identifying me as “The Entire Polish Army.”

I occasionally visited the local hobby shop in town run by a man named Konrad Kelm. Konrad had served in the U.S. Navy in Japan and while there had taken the opportunity to study Japanese art. He had a marvelous talent for drawing, which he did while tending the store, so there was always something on his easel behind the counter. The first time I visited Konrad’s store was in 1960 when I was 15; we began to talk, and he showed me a paperback book he was reading, Jack Kerouac’s Dharma Bums. He asked if I knew Kerouac. When I said I did not, he said I had to read him and he gave me the book, introducing me to one of the most important writers of the period. I would frequently drop by his store to see the progress of his latest drawing or painting and we became friends. I begged my mother to give me $25 — a lot of money in our family and more than I had ever asked her for — to buy one of his drawings, which still hangs on a wall in my home.

The influence of both Di and Konrad led me to take an interest in Japanese literature and I spent my lunch money, saved over several weeks, to buy R.H. Blyth’s four-volume Haiku collection and his two-volume history of Haiku, written in English but published in beautiful illustrated volumes in Japan. I treasured those books.

A First Generation College Student

I was the first person in my family to go to college, my mother having dropped out of school in eighth grade to go work in a factory and my father having dropped out in tenth grade to work on a vegetable truck. My stepfather had quit high school at 16 and falsified his birth certificate to join the Navy. I had no guide to the world of higher education, though in California it was free and virtually open to all. I studied English Literature at nearby Southwestern College in Chula Vista, a two-year state community college, and then went on to San Diego State College. The New Criticism was dominant then, a highly formal approach to literature that eschewed biography, history, or sociology, making literary theory pretty dull. Only in my senior year in the summer of 1968 did a professor assign a book that seemed relevant to the world in which I lived: Georg Lukacs’ The Historical Novel, which looked upon literature as an expression of society and its class struggles. Here was a book that discussed revolutions and novels at the same time. I immediately recognized that this was what I had been looking for.

In school I was also drawn to Bertolt Brecht’s plays and his theories of the theater, especially the alienation effect. I was also interested in its opposite, Antonin Artaud’s theory of the theater as plague. I became a close friend of one of the English professors, Jackie Tunberg, who wrote an an anti-war play that we produced in San Diego, in which I played a gay department store manager who instructed Santa Clauses in how to play their roles. Jackie also introduced me to The Guardian Newspaper, the old leftist newspaper that covered everything. Jackie’s husband Bill Tunberg was a Hollywood screenwriter (he wrote Old Yeller) and a friend of Dalton Trumbo and the Hollywood Ten. From their stories I learned something about the impact of McCarthyism. Partly though Jackie and her friend Marc Zimmerman I was becoming part of the left, if not yet part of the activist movement.

During those years at San Diego State, from 1966 to the summer of 1968 when I graduated, various developments in the world — especially the Vietnam War and the rise of the black power movement — challenged my socialist pacifist identity. In the summer of 1968 I wrote from my pacifist point of view an essay criticizing the Black Panthers for their advocacy of armed self-defense and sent it to The Good Morning Teaspoon, San Diego’s underground newspaper. The minute I put it in the mailbox, I regretted it. I realized the Panthers were right and I that I was wrong; they had to defend themselves guns in hand. Thankfully, as far as I know, my letter essay was never published. About the same time I read Jean Paul Sartre’s introduction to Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, in which he argued that my kind of pacifism was a luxury impossible for people in the situation of the Vietnamese. I was convinced. I decided that I would have to stand with the Vietnamese and the Panthers. By 1968 I had given up my family’s pacifist socialism for my own radical views.

I had meanwhile gotten married at 18 and divorced at 19. I graduated from college with a B.A.. in English and no idea of what I would do. But in those days, when college was free and jobs were plentiful, I was less worried than I was curious about what life would bring me. I was adrift in the sea of life, snatching up the books that floated by.

What Will I Do with My Life — What Will I Read?

Coming from a family of socialist pacifists, I had already registered as a conscientious objector in 1963 and I had joined some early protests against the war — and, in the mid-60s, over rising tuitions — but I had not really become part of “the movement.” I had spent most of 1968 dealing with personal issues, finishing college and trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. After graduating from San Diego State College, I tried a graduate program in Librarianship at the University of Chicago. Once I became bored with it, I went to the Regenstein Library and read German novels: Thomas Mann, Herman Hesse, and Hans Habe. I dropped out after one semester. While there I joined a picket line to protest against Dow Chemical Company, which made the napalm being dropped on peasants in Vietnam.

In the summer of 1968, at the age of 23, I returned to my hometown of San Diego, California, now in my second marriage, my wife Barbara pregnant with our son Jakob. I got a summer job with the San Diego City Planning Department doing a survey of housing in the Mexican–American border town of San Ysidro, which involved interviewing residents, almost all of whom were Spanish-speaking, low-income workers. I asked them questions about their lives, about their work, income, family, and housing. At the same time, I was asking myself a big question about mine: What was I going to do with my life?

UCSD: Herbert Marcuse and Fredric Jameson

One day an older friend, Helen Rowan, invited me to accompany her to a series of lectures at the University of California San Diego that she thought might interest me. The speaker, it turned out, was Herbert Marcuse who was giving three nights of lectures about his book One-Dimensional Man, which brilliantly combined Marxist methods with contemporary sociology and media studies to argue that Karl Marx’s belief that the working class would lead a socialist revolution was wrong, at least in modern America. The system had proven capable of neutralizing the working class, through the promotion of consumerism, the expansion of personal and sexual freedom, and the construction of a compelling ideology of equal opportunity. I had come of age in a working class town, gone to a mediocre high school, and studied at community college and finally San Diego State College. I had never had any brilliant intellectual teachers. Marcuse’s lectures represented my first experience engaging with a marvelous mind, a world-class intellectual. I was hooked.

After the lecture series, I went to the UCSD campus in La Jolla and asked to join the Philosophy Department to study with Marcuse. I was told that there was no room: Marcuse had brought along with him to UCSD his graduate students from his old post at Brandeis University, and others from around the world were flocking to study with him since he had become what Time magazine called “the guru of the New Left.” Refusing to be defeated, I walked around the corner to the Literature Department and was accepted there as a graduate student. I was assigned to work as a teaching assistant with a young, unknown professor named Fredric Jameson, who would later become famous as a major left intellectual of the era. Serving as his TA for the humanities sequence, I was dazzled by his lectures on Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, a brilliant critique of Christian bourgeois morality from an elitist point of view.

In my first semester I signed up for Jameson’s seminar on Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason, then available only in French. I had studied French in high school, but didn’t know much and found myself learning to read the language while becoming immersed in the questions of the relations between psychoanalysis, existentialism, and Marxism. Angela Davis, a Marcuse graduate student, occasionally dropped in on the seminar but didn’t regularly attend. I also enrolled in Anthony Wilden’s course on his then new book The Language of the Self, a study of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Between the two courses I found myself immersed in the French intellectual world existing somehow amidst cactus and chaparral on the La Jolla mesa.

Simone de Beauvoir, herself a brilliant writer and Sartre’s companion, tells us Sartre wrote The Critique of Dialectical Reason, more than 700 pages in tiny print, while he was taking the drug Benzedrine. Perhaps that’s why the book has something manic and obsessive about it. But its questions were inherently fascinating. The opening section, which had been translated and published under the title A Question of Method, asked what is the relationship between the personal, the social, and the political? How do we grow up into our class? How do we become who we are in both personal and class terms? As a young person in the university, my peers and I were able for several years to float between social classes, in my case between my working class family and the possibility of a middle class professional life, so the question of class identity and how one assumes it was very personally engaging. The body of the book investigated the question of the relationship between social movements and their institutionalization. It asked how our movements congeal into organizations, parties, and states; surely one of the most important question facing revolutionaries if they wanted to preserve democracy and avoid the pitfalls of bureaucracy.

In that course, we also read Alexandre Kojève’s Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, based on his lectures. For my fellow students, I translated into English the section on “The Master-Slave Dialectic,” Kojève’s reading of an important section of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind. Kojève read the master-slave relationship not only as a struggle for power but also for recognition, one that demonstrated the potential power of the slave. After Jameson mentioned their importance, I also bought and read into Jean Hyppolite’s French translation of The Phenomenology of Mind (Phenomenology of Spirit in his translation) and his two-volume companion book Genesis and Structure of the Phenomenology of Spirit. We read Hegel at that time not only because of his relationship to Sartre, but also because of Hegel’s importance for Marx, the founder of modern socialism.

Anthony Wilden and Herbert Marcuse

Anthony Wilden’s seminar on Jacques Lacan involved reading a lot of Freud, beginning with The Interpretation of Dreams and several of his most important case studies. Wilden focused on “Little Hans” in particular because of it centrality to Lacan’s theory of “the mirror stage,” the recognition of oneself. Wilden complemented this with the intellectual biography Freud by O. Manoni, a student of Lacan. We read these in conjunction with Ferdinand de Saussure, the Swiss founder of the field of semiotics, that is, the study of how signs give rise to meaning. And we read Claude Lévi-Strauss, the structural anthropologist and one of the central figures of the structuralist movement. Reading Freud and Lacan complemented and challenged the reading of Sartre, who rejected the existence of any unconscious or subconscious. The plunge into Freud at the age of 23, in the midst of the sexual revolution that accompanied the development of the birth control pill and the collapse of many sexual taboos, and in the midst of my own romantic and sexual turmoil, absorbed and fascinated me.

For a while I was assigned to work as a research assistant for Wilden, who had taken an interest in general systems theory. He would send me to the library in search of books by Ludwig von Bertalanffy, the theoretician of general systems theory, and other authors, to be delivered in stacks to his office in the cabins among the eucalyptus trees at midnight when he was sure to be found there. I would ride up on my bike and see Wilden in his office, there in his cabin in the woods at midnight, a Mephistophelean figure, sitting at his desk, his books spread out before him, or springing up to pace about the room, searching in Freud, Lacan, and Bertalanffy for the meaning of it all.

At the same time, Marcuse was teaching an undergraduate course on Karl Marx, with an emphasis on the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. His Wednesday night lectures were attended by a hundred or more registered students, scores of other undergraduate and graduate students, interested locals, as well as many professors. One night Marcuse introduced “my old friend Erich Fromm,” the psychoanalyst and social theorist, who had come to visit. Marcuse was, in his mannered, old-school way, charming, and his lectures, delivered in a heavy German accent, were brilliant. The rightwing Young Americans for Freedom would show up to picket and we on the left would ridicule them. I remember another night when I was holding my infant son Jake in my arms; he began to cry and I started to leave the lecture. Marcuse said loudly, “Don’t you take that child out of here. I want to get them while they’re young and malleable.” On another occasion, at the conclusion of a class, he shouted gruffly in his Germanic English, “Und now vere all going to vatch Battle of Algiers,” Angela Davis leading the hundred or more in the lecture hall to the film screening.

We fell in love with Marcuse’s mind, his method, his scholarship. We read everything he wrote. I was particularly taken with his early book Eros and Civilization, his attempt to merge the fundamental principles of Marx and Freud. I especially loved the way that Marcuse attempted to complement the Marxist concept of work with Friedrich Schiller’s idea of play — raising the idea that really free work would have the character of play. His book on Hegel and Marx, Reason and Revolution, was high on our list because we wanted to understand the intellectual origins of revolutionary Marxism. Later, a year or two later, after I had read Leon Trotsky’s Revolution Betrayed and Max Shachtman’s Bureaucratic Revolution, Marcuse’s Soviet Marxism also contributed to my developing and deepening socialist and anti-Stalinist views. All three in their different ways provided a critique of the conservative, bureaucratic, and stultifying nature of Soviet society and its intellectual life.

While we loved Marcuse’s mind, we didn’t necessarily agree with the political analysis and the programmatic conclusions that he was drawing. Certainly I didn’t. In An Essay on Liberation, published in 1969, he argued that since the working class had been neutralized, the future of any revolutionary movement lay with the young intellectuals, the masses of the black ghettos, and with the Third World peasant movements. At times the book seemed to suggest that some philosopher-king like Marcuse himself would guide this revolution of the marginalized. The idea of an alliance between the intellectuals and impoverished and desperate masses struck me as an elitist strategy. But this critique came later, after I had become a Marxist, read Hal Draper and joined the International Socialists. I had come to believe that the future lay with the self-emancipation of the working class.

On behalf of the local chapter of Students for a Democratic Society I asked Marcuse to give us a talk about the Paris Commune. He had us read Frank Jellinek’s old classic The Paris Commune of 1871, since no talk could be done without a reading. When Marcuse taught that class, he spoke as a Marxist, not as the Marcuse of the 1970s. His talk was all about workers’ power, democracy, and revolution.

In my first class at UCSD, the Jameson course on The Critique, I became friends with Ran Mitra. Ran, who had started out studying physics before turning to philosophy, had now become a comparative literature student. My wife Barbara and I and he and his wife Dianne, who was studying with Marcuse, all lived in the UCSD married student housing and their son Kinjal was the same age as our son Jake. Ran and I spent a good deal of time together both as students and as young fathers. walking our boys to the playground and talking about Marxism. Ran gave generously of his time, shared his ideas, and was incredibly patient as a mentor and a friend. As an Indian, who identified with the Indian Maoists or Naxalites, Ran frequently challenged my developing socialist ideas. Who would prevent a socialist workers government from exploiting the peasants, he asked?

Occupying the UCSD Administration Building

I joined the UCSD chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) immediately after arriving on campus. We rallied regularly, hundreds of us every week, in opposition to the Vietnam War or in support of the civil rights and Black Power movements. At the time, the UCSD campus on La Jolla Mesa — where coyotes prowled the outskirts and rattlesnake bites frequently led to the hospitalization of students — was isolated from the city of San Diego, from the working class, and from the black and Latinx communities. Our SDS chapter focused on anti-war work among the UCSD students who were mostly studying science and math and looked forward to jobs in the aerospace industry; that is, in what President Eisenhower had called the “military-industrial complex.” One of our best tactics was to make visits to the dormitory suites where we would knock on doors and invite the pretty conservative engineering students to come into the common area to discuss the war. We had some very serious discussions and changed some minds.

We on the left were engaged in many activities in those years. One day, in the midst of our weekly SDS rally, Angela Davis appeared to tell us that the black, Latinx, and Asian students were going to occupy the administration offices. They were demanding that UCSD’s third college, then in the planning stage, should be a Third World school called the Che-Lumumba College (which was also the name of the Communist Party’s club in East Los Angeles at the time). Marching off to the building, Angela told us we could join the students of color in the occupation, which was going to take place immediately. Those of us in SDS had never been informed of the plans for the occupation — we were just told to follow the students of color as they occupied the building. I and some others rejected that political method — of demanding unquestioning loyalty — and at first hesitated to follow behind, but after standing outside smoking Gauloises Disque Bleu cigarettes for a while with my friend Helène Frances, we decided to join the occupation.

Once inside, my friend Ran came over and told me that I should be aware that Angela had invited some of her friends from East Los Angeles who were not students, some of whom were armed. We occupied the administration building for several hours, some of the occupiers rifling through cabinets full of confidential papers. After several hours some sort of agreement was reached and we were able to leave without any violence taking place. I was relieved to be out of the building without incident, but angry that I had been inveigled into participating in what turned out to be an armed occupation of the building. I believed that people had a right to be informed and consulted about such a serious decision, that people should never be used as pawns by a political movement and its leaders.

On another occasion, less exciting and much less perilous, as a parent I also joined protests to demand that the administration create a childcare center, and we parents with our infant and toddler children occupied the administration offices, changing dirty diapers on the desks to make our point.

A group of us in the Literature Department meanwhile established a graduate student-initiated and -directed seminar with the support of Jameson, Wilden, and Carlos Blanco Aguinaga, a Spanish Communist writer and professor of Spanish literature. For several semesters we read and studied Hegel, Marx, Freud, Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georg Lukacs, Lucien Goldmann, and others of that ilk. We also read and discussed some Lenin and Mao, as I remember, but Jameson, at least at that time, was allergic to Leon Trotsky’s theories, so he was proscribed.

Several of these thinkers were interesting and important to me. I found Sartre’s existentialism, as laid out philosophically in Being and Nothingness and popularly in Simone de Bauvoir’s wonderful little book The Ethics of Ambiguity, a completely rational approach to understanding and living one’s individual life. Sartre saw himself as a Marxist and he attempted in The Critique and other books to offer a social analysis as well and I came to think of myself as an existential Marxist. I thought that Merleau-Ponty’s critical Marxism, as laid out in his books of the late 1940s, was also very attractive. In that period, both he and Sartre tried to maintain a “neither Washington nor Moscow” position, until the space for that seemed to disappear with the heightening of the Cold War.

As a student of literature, I particularly liked Georg Lukacs and Lucien Goldmann, both of whom argued that literary forms arose from ideologies that were rooted in social classes. For literary studies it was a powerful idea, much more interesting and valuable than the common American sociology of literature that related, say, a novel’s content to social history. While that method was certainly useful, the concept of Weltanschauung or vision du monde — that is, a worldview that grew out of material life, out of property relations, and out of class struggle, and the novel as an expression of that in form and content — was far more interesting to us. Lukacs had as a young revolutionary participated in the Hungarian Communist government of 1919, but he later accommodated to Stalinism. His knuckling under to Stalinism and to the bureaucratic Communist system — despite his criticisms of it and even his participation in the Imre Nagy government of 1956 — was extremely disappointing and disturbing.

I remember that once during those years of 1968 to 1970, while we in the student-initiated seminar were in the middle of discussing some text, a group of student protestors happened to march by our window, and without a word said we all closed our books and got up, left the classroom, and joined the march — an event that seems to me to symbolize the entire period.

Humboldt State College

After my first year at UCSD ended in June of 1969, my mind was blown. I needed a break form the seminar room. I needed a pause to assimilate what I had learned. Deciding to take a year off to teach, I got a job as a Lecturer in English Literature at Humboldt State College, near Eureka in Northern California, and headed off with my wife and infant son. When we arrived that summer, I had no job, so we applied for welfare and got food stamps until work began in early September. I also signed up for a course that summer on the events of May and June 1968 in France offered by Carl Ratner, a young psychology professor. We read several journalistic accounts of the French strikes published in mass market paperbacks. The books were pretty good, though we did not yet have Daniel Singer’s account. The class was small, about a dozen students, all radicals; among them was Walt Sheasby, a sociology student and a remarkable local activist. Walt and his wife Madeleine and I and my wife Barbara became close friends, both of us with children, our Jakob and their Frea. Walt, who had been a member of the Independent Socialist Clubs (ISC) in Berkeley, held the “Third Camp” socialist views developed by that group’s intellectual leader, Hal Draper. The Third Camp socialists opposed both capitalism and Communism with a capital “C” — that is Stalinism. Their slogan was “Neither Washington nor Moscow, for International Socialism.”

Several us who were members of the class on the French May events came together with a few other students and locals to create an independent socialist collective, of which Walt was the instigator and leader. We decided that we should be part of some national left organization, so we invited speakers to come from all of the groups we could think of. Eugene Nelson, who had written a little book, Huelga: The First Hundred Days of the Great Delano Grape Strike, about César Chávez and the United Farm Workers, came to represent the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Bettina Aptheker, an activist at the University of California at Berkeley and the daughter of Communist historian Herbert Aptheker, came from the Communist Party. Robin Mazel of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP) visited and talked mostly about Cuba. There was also a very young woman from the Progressive Labor Party who made a poor impression on us because she seemed to be simply reciting a party line that she herself had just been given and did not understand. Walt, who had begun to guide me toward his Third Camp political position, asked questions of each of these speakers, questions that revealed their weaknesses: the IWW’s lack of a political perspective, the conservatism of the Communist Party, and the SWP’s adulation of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

Walt had saved for last visitors Jack Bloom and Stephanie Beatty of the International Socialists (IS), the successor to the ISC. I was impressed with the IS members’ talks, which emphasized the important role that socialists could play in building a new revolutionary labor movement and a revolutionary party. When I asked Jack Bloom when he expected the American socialist revolution to take place, he replied that it would be coming soon and certainly within twenty years (that is, by 1989). At the time, given the tremendous upheaval taking place around the world and in America — civil rights and black power, the ghetto rebellions, the anti-war movement and women’s liberation — that date did not seem unrealistic to me.

Joining the International Socialists

After hearing all of the groups, our little collective split, a few joining the Communist Party and several others, Walt and Madeleine, and Barbara and I among them, joining the International Socialists. I joined the IS, however, only after reading Hal Draper’s essay “The Two Souls of Socialism” and Stan Weir’s article “The New Era of Labor Revolt.” Draper argued that socialism had two traditions, one found in Social Democracy and Stalinism that attempted to hand down socialism from above. The other, found in Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky, argued that socialism had to be created from below. Weir, analyzing the contemporary American labor movement, pointed out that there had developed in some sectors, such as the building trades, new worker movements for union democracy and for a more militant attitude toward the employers. The ideas in the pamphlets — the necessity of democracy and the centrality of the working class — came to form the heart of my thinking. These ideals seemed to me to be extensions of my grandfather’s socialism and my mother’s loyalty to her retail clerks’ union. While offering a vision of socialism, and expressing the need for organization, they took into account the creative activity from below that was taking place all around us. The IS’s notion of socialism from below coincided with what were now my feelings and my ideas about socialism. I had found a political home. At the time I had had a large poster of Mao in my office. I suppose I had put it there because we all identified Maoism — about which we knew nothing — as some sort of popular democracy, but after reading Draper, I took down the poster and threw it away.

After joining the IS, every once in a while Barbara and I would make the long drive — about 300 miles and six hours — to visit the group’s Berkeley branch. We got to know a few IS members, among them Dave McCullough, who was a Buddhist and a socialist. I found that IS members, unlike the Trotskyist sects, read everything, and from one of them I learned about Victor Serge, the former anarchist who became a Bolshevik and the conscience of the Russian Revolution. Only a couple of years later would I read Serge’s Memoirs of a Revolutionary and only much later his many other writings: novels, essays, and most recently his notebooks. Serge, though originally an anarchist, had stood with the Russian Revolution of October 1917, but was also willing to challenge even the revolutionary leaders whom he followed.

Back in the town of Arcata, where Humboldt State was located, a guy named Jerry Gorsline had a nice little bookstore. Walt and I spent a good deal of time with Jerry, drinking coffee and discussing books. Jerry was perhaps 30 at the time, five or six years older than Walt and I, and he made his living with textbooks but stocked the shelves with lots of leftist stuff. I remember buying André Gorz’s Strategy for Labor, an expression of my awakening interest in labor unions and workers. I had grown up in a working class family that was pro-union, yet, until joining the IS, I had never thought much about labor unions, their role in society, and their potential social power. The IS argued that the working was not only the majority of our society, but that the industrial working class stood at the center of the capitalist economy, with the power—as the Industrial Workers of the World had put it in the early twentieth century — to stop the wheels from turning and bring the system to a stop. We thought at that time — a little simple-mindedly — that an economic crisis would almost automatically lead the workers to rebel and do just that: lay down their tools, stop the machines, rise up and seize the state. Gorz suggested that unions should act politically and raise “non-reformist reforms, thus pushing toward a socialist transformation. Such an idea was altogether new and fascinating to me. I continued to read Gorz, even after later, in another book, he said Farewell to the Working Class.

Meanwhile, still under the influence of graduate school, I had ordered Luckas’ History and Class Consciousness (in French because it was not then available in English) and read the chapter on “Reification and Class Consciousness.”. Luckas made the argument — very crudely summarized — that the very alienation of the working class gave it a revolutionary perspective on society. I attempted to use Lukacs and the other things I had studied in graduate school to teach my course on the introduction to the literary genres (the epic, drama, the novel, the story, poetry). I think my students, all undergraduates and mostly studying forestry, the college’s specialty, must have found my lectures utterly incomprehensible. I was, no doubt, a terrible teacher during that first year.

The 1970s Anti-War Strike

While I was studying and teaching, on April 30, 1970 Richard Nixon announced that he was expanding the Vietnam War to Cambodia, and immediately student strikes swept the country. For months before, Walt and I and a few friends had been going once a week to the campus free speech area, standing on the giant redwood tree stump and giving talks against the war, usually to a dozen students. That week when we stood on the stump, hundreds of students massed in front of us. Walt took them on a protest march through town, a first for us. In the next couple of days Walt organized a campus meeting attended by 3,000 of the campus’ 5,000 students, who voted to strike. I was the only professor or instructor involved in the organization of the strike, and Walt and I were at the center of it, organizing the nearly nightly steering committee meetings. Jerry Gorsline’s bookstore became the strike headquarters, with a half dozen newly installed telephones. Meetings went on there day and night for a couple of weeks. The college ombudsman approached Walt and me and asked us if we could end the strike. We told him we could not and would not. Eventually the strike wound down and we returned to class. If UCSD had immersed me in the vibrant intellectual left world, my experience in the Humboldt State student strike had given me my first involvement as part of a real mass movement.

Women’s Liberation

While we were living in Arcata, my wife Barbara and Walt’s wife Madeleine began to become involved with other women in a consciousness-raising group, where they discussed their personal lives, their love lives and their marriages, their work, and politics. These groups also naturally read everything they could lay their hands on that seemed to help explain women’s situation. They read, of course, Friedrich Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, the Marxist explanation of women’s oppression. But 1970 brought three books that became central texts of the women’s movement of that time. Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, combining Marx and Freud, called for a radical revolution that would abolish sexual oppression and even sexual difference itself. Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch described women’s utter subordination to men. Finally, Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics, published the same year, provided the women’s movement with a radical political program. These books led women back to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, the first radical feminist critique of women in modern society. And, of course, because the women were reading these books, we men did too — or, at least some of us read some of them.

The women with whom I was involved in those years, inspired by their consciousness-raising groups and the new sense of self-respect and self-worth that they had found, challenged men at every turn—and I was one of those that they challenged. My experience of the relations between men and women had been formed by my patriarchal grandfather, by my philandering father, by my teacher Leroy’s predatory attitudes toward women. Yet, on the other hand, my mother’s strength, independence, and critical attitude toward male presumption had also had an impact. My mother fought for her liberation throughout my life, divorcing my unfaithful father and later leaving my alcoholic and sometimes violent stepfather.

I had my first real romantic and sexual relationship with Winifred, a fellow English student at Southwestern Community College in Chula Vista. At 18 we married. This was not unusual to me. Many of the guys in my graduating class married their girlfriends while still in high school or just after graduating, often because the girls were pregnant.

Winifred and I went to San Diego State College together, modeling our lives on our friends Leroy and Karen. We both studied English, we both worked, and we shared the housework. Our egalitarian partnership was not inspired by women’s liberation; rather it was driven be a desire to achieve membership in the middle class, to earn a B.A. and later an M.A., to get jobs as teachers with a good salary and with three month vacations in the summer. We were partners, equals in pursuit of a better life. Then she fell in love with our best friend and went off with him. I was hurt and sad, but also relieved: it had not been right for either of us.

Soon after Winnie left me, I met Barbara, an art student at Southwestern College who played the guitar. She was open and loving, funny and imaginative, a victim of sexual abuse and suffering from mental illness, a radical and a rebel. We were partners, but because of the nature of Barbara’s mental health problems, partnership proved difficult. She might stay home from work and lie in bed eating candy or ride off with a guy on a motorcycle for the day, she might leave the house with the iron on, burning the clothes on the ironing board, or leave the water running in the bathtub. She found it hard to stay on track to achieve her own goals. Women’s liberation became her cause when she discovered it; it spoke to her earlier history of abuse, in particular.

Women’s consciousness-raising groups sometimes took place in our house. One night the women gathered at our place. I had been out at a bar, and when I came home and started to open the door someone slammed it in my face, practically knocking me down the stairs. I didn’t realize that inside women were using a speculum to look into their own vaginas.

I was no paragon of feminism. Barbara and other women challenged me for my sexist stereotypes or sexist language, for my male presumption. The women’s movement often made me feel defensive and sometimes resentful, and even excluded from the club. Yet at the same time, I felt proud of Barbara and the other women, who were part of our movement and building their own movement, sometimes within and sometimes in parallel. We were creatures of the society in which we had been raised, attempting to become better people. And the women were definitely leading us in that process, which was often difficult and sometimes painful.

Back to San Diego

When Barbara and I returned to San Diego, now members of the International Socialists, we found that our friends in SDS had joined the Progressive Labor Party. This was just after the PL had played a decisive role in destroying SDS nationally, though out on the West Coast we had been oblivious to that disaster. PL transformed our friends. Once a typical group of southern Californians of the late 1960s or early 1970s, the men with long hair and beards, t-shirts, and blue jeans, and the women with their long, loose hair and folksy homespun style dresses, they suddenly changed. The men now got crew cuts, put on suits, and told us that the PL was sending them into the working class. The women adopted more conservative attire as they too headed into the proletariat. Our old friends’ way of talking had completely changed as well. We could no longer talk with them casually as we once had. They had become robotic, looking at us as if we were strangers, and spouting a party line to us. Those who joined PL had become Third Period Stalinist sectarians, sure that the revolution was around the corner, that they were the only revolutionaries, and that we were not of their ilk. We had known them in SDS, which had been so open, so democratic, so vibant. We felt both sad and disappointed that our friends had joined what appeared to be a left cult where leaders directed followers in the old Stalinist style.

Now on our own, Barbara and I and a couple of friends organized within the local anti-war organization a study group on Vietnam. Sitting on the floor of our married student apartment with half a dozen others, we threw ourselves into the study of Vietnam. We read Jean Lacouture’s book Vietnam Between Two Truces and Robert Scheer’s pamphlet How the United States Got Involved in Vietnam. As Third Camp socialists, we attempted to convince those in the reading group that one could oppose the U.S. imperialist war and support a military victory for the Vietnamese people without supporting Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnamese Communist Party politically. We read and discussed the history of the Vietnamese Trotskyists, whose leader had been assassinated and party destroyed by the Communists. We won over a couple of people, but in truth we had little success. The student movement had become uncritical supporters of Ho, and in many cases also of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. I believed that Vietnam and Cuba had to be defended from the United States, but that their political systems, based on the Soviet Union’s one-party-state model, must not be supported uncritically.

Pretty isolated at UCSD and hungry to learn more, Barbara and I joined a study group on Leon Trotsky’s writings organized by the Socialist Workers Party that met in downtown San Diego. We read with them Trotsky’s The Third International after Lenin, an important book about the transition from the early revolutionary International to Stalin’s International. We found the Socialist Workers Party’s approach to education altogether different than our experience in the classrooms and in the movements at both UCSD and at Humboldt State College. While our earlier reading groups had been based on an exciting give-and-take and a common search for understanding, the SWP’s method was about indoctrination. We were being taught a dogma, and that attitude made the course unattractive and uninteresting to us. We dropped out.

The International Socialists, perhaps because it had only been founded in 1969, didn’t have much of an education program, at least at first. We read New Politics, an independent journal that published Draper and IS members. As suggested by our IS comrades, we read things by and about Trotsky. We read over the next few years Isaac Deutscher’s marvelous three-volume biography, and Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution, The New Course (with its wonderful introduction by Max Shachtman), and The Revolution Betrayed. Only later would we read Trotsky’s writings on the Spanish Civil War and the rise of Hitler and Nazism in Germany. We were all obsessed with “the Russian Question,” that is, what had happened to the Russian Revolution and how had the Soviet Union degenerated into a dictatorship and an imperial power. We spent days in reading and hours in debate about that topic, which is understandable given the Cold War, the importance of the Soviet Union in the world, and the USSR’s relationship to the developments taking place in Cuba and Vietnam. Clearly the question of how a Marxist-inspired workers revolution went wrong was a problem that deserved our attention if we hoped to make a revolution in our country and prevent it from also going astray.

Our little International Socialist group at UCSD, just a handful of people, began to do some strike support with the United Farm Workers (UFW) and with the Greyhound Bus Drivers who had walked out. The UFW had a strike going on down near Imperial Beach, so I drove down there and went to the meetings and picket lines, sometimes with my mother. At the same time the national IS had launched a discussion of what we called “industrialization,” that is, the effort by members to get factory jobs in order to build rank-and-file groups in the labor unions. We held national discussions about the nature of the labor union officialdom and the role of rank-and-file workers. Unlike the PL members who went off to lead the working class, we went off to immerse ourselves in it, sure that we had important ideas to offer, but also anxious to learn from the workers themselves.

A Trip to Mexico

At the age of 26, I had never traveled to a foreign country, except just over the border to Tijuana, but in 1971 I took my first real trip abroad. I traveled with a friend by train from Mexicali to Mexico City, arriving just after the Corpus Christi Massacre, when Mexican soldiers known as the Hawks (Halcones) had attacked and killed about 120 students on strike at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). We went to the campus but found it occupied by troops and largely abandoned. In the bathroom, however, I found a sticker announcing a meeting of the Electrical Workers Union (STERM), a union that would soon lead the Tendencia Democrática, a national workers reform movement. So we went to the meeting. We found the workers at that meeting looking anxious and fearful following the police murder of the students. But they pledged to continue their fight for democracy and workers’ power. It was my first experience at a labor union meeting.

In the center of the city on the Alameda Central we found a leftist bookstore called El Sótano. As it happened, Adolfo Gilly’s new book La Revolución interrumpida (The Interrupted Revolution), which had just been published, was just being put out on the book tables. I also bought a copy of Jesús Silva Herzog’s more or less official two-volume Breve Historia de la Revolución Mexicana (Brief History of the Mexican Revolution.) I read Gilly’s book on the bus on the way home, thrilled by his account of the revolution and impressed by his Marxist analysis of it as an incomplete one. These books became the foundation of my Mexican history library and of my now nearly fifty-year interest in the country and its history.

In late 1970 and early 1971, I was becoming unmoored. Back in graduate school, I became a semi-dropout. I quit attending my seminars in my supposed major of English Literature — skipping, for example, a course on “Prospect Poetry of the Nineteenth Century” — and I stopped doing the reading and writing, though I continued in the graduate student seminar on Hegel, Marx, Freud, and Sartre. On my own I read more Marx and Lenin, Trotsky, and Shachtman. Emotionally and intellectually, I had begun to leave graduate school, though it would take me another year to completely abandon ship.

Into the Working Class

My life was turned upside down at this time. In part, it was the turbulent times. In part it was the seething social movements. In part, it was just me. Barbara and I were young. We had really been in love, but we had grown apart. We separated and divorced when our son was just approaching three years old. I took custody of Jake.

We in the IS — there were about three hundred of us — had all become convinced of the importance of taking socialist ideas into the working class, though there had been great differences about our strategy. Remember that this was the era when George Meany headed the AFL-CIO, Walter Reuther led the United Auto Workers, and Jimmy Hoffa ran the Teamsters. All were different obstacles to union democracy and militancy. At the same time, Miners for Democracy provided an example of workers challenging a conservative, corrupt, and violent leadership and winning.

What were we to do? Some of our older members worked in the labor bureaucracy, like Anne Draper (wife of our leader Hal Draper). A few of our members had jobs as teachers or social workers and were active in their unions. A couple had gone off to get industrial jobs as an experiment. We debated the nature of the labor unions: Were they inherently conservative? Or could they be reformed? And if so, how? How could we take socialist ideas into the working class? We decided that we ourselves would have to get industrial jobs, would have to become active in the union, and would have to build rank-and-file movement like the MfD in the industries.

So Barbara went off to Detroit to work in an auto plant and I and my new companion both dropped out of the university, and then she with her child and I with Jake, went off to Chicago to join the IS branch there.

I worked in a number of jobs in the first couple of years, first as a librarian and then as a social worker until I eventually found a job in a steel mill and later as a truck driver. I would spend about six years as an activist in the Teamsters union and later in the reform movement Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU).

Once I was in Chicago, our reading changed as our group began to orient to the labor movement. We had only a few old timers to guide us — Stan Weir, a longshoreman on the West Coast, and Steve Zeluck, a schoolteacher on the East Coast — so reading about the history and the contemporary situation of the unions was essential. We read the documents by our group’s leading intellectuals, outstanding among them Dave Finkel, Kim Moody and Robert Brenner. We studied such organizations as Miners for Democracy, the “dues protest movement” in the United Steel Workers, and the Teamsters United Rank and File (TURF). We began to read deeply in American labor history, the overarching studies such as Irving Bernstein’s trilogy, Art Preis’ analysis of the CIO and New Deal era, and Philip S. Foner’s monumental history of American labor, as well as Alice and Staughton Lynd’s oral histories, and many studies of particular industries and unions. The purpose of that reading was to prepare us to work in industry and to develop strategies for struggle in the unions.

I know that with the privilege of graduate school, I may have read more widely than many of my comrades. On the other hand I also know that the IS had many members who were better educated than I. Our political tendency definitely had a set of central texts — Marx, Lenin, Luxemburg, Trotsky, Shachtman, Draper — and many of us also read Victor Serge and considered him the moral compass of the left. I found that people in the IS tended to read more broadly than many of those in other groups who kept to the straight and narrow path of their group, whether that was Stalin, Mao, or Trotsky. I believe that our members’ broader political culture militated against creating a dogmatic sect, though at moments we veered dangerously in that direction. Dogma has its attractions: it lays out a clear path, it provides one with a life course, and it predicts victory. It is, of course, an illusion. A reading of our history — and we read a lot of that — suggests that there is no clear path and no assurance of victory, but such reading also suggests that the difficulties we face are worth the fight to achieve a truly human society.

I had many friends who read in order to better make the revolution and to make the revolution better. Our reading in 1968 and thereabouts, done in the context of mass movements of social protest, helped to transform us into revolutionaries. Many of us, committed to building a socialist movement based in the working class, later became telephone workers, autoworkers, steelworkers, and truck drivers, some for decades, some for only a few years. Others were leaders in the anti-war movements or in community movements, and later in the LGBTQ and environmental movements. After the movements subsided in the mid-1970s, some returned to graduate schools to take academic degrees in philosophy, history, or literature, and some also studied law. Even after they left their industrial jobs, many continued to put their intellects and their knowledge at the service of the working class. We continued to be activists, and we continued to read, always reading toward the revolution.

Dan La Botz and his wife Sherry Baron live in Brooklyn, New York, near two of their children and one of their grandchildren. Dan teaches at the Murphy Institute, the CUNY labor school, and is a member of both Solidarity and the Democratic Socialists of America. Verso published his book Rank-and-File Rebellion: Teamsters for a Democratic Union in 1990. He is the author a ten other books on labor and social movements and politics in the United States, Mexico, and Indonesia. La Botz is a co-editor of New Politics.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]