Superpredators: Police on the Hunt

Police often speak of themselves as hunters. This might best be understood as an honest admission of what they actually do: hunt, capture, cage, and often kill those subjects marked as fugitive, unruly, impolite.

Police: A Field Guide is on sale for 40% off until Sunday, April 1 at 11:59pm EST.

The world is made up of two classes — the hunters and the huntees.

–"The Most Dangerous Game," 1924

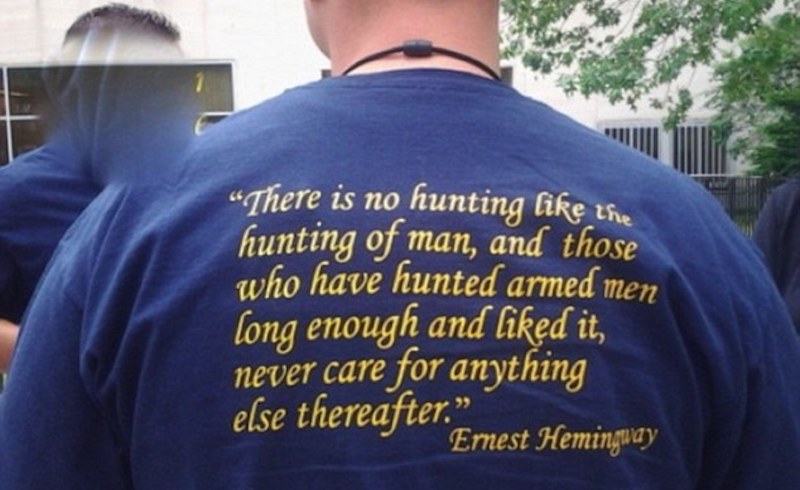

In June of 2013 members of the NYPD’s Warrant Squad were spotted wearing shirts displaying a passage from Ernest Hemingway: “There is no hunting like the hunting of man, and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never care for anything else thereafter.” In response, some concerned citizens expressed their disapproval. “I find it highly offensive for the NYPD to have an official shirt with this on the back…You don’t hunt men, you hunt animals.” Another person exclaimed, “I don’t think that human beings should be hunted down like animals, cops are here to serve and protect.” 1 This seems like a reasonable response, but what if this is one time we take police at their word, despite their propensity for “testilying” and generally distorting facts and the truth?

Rather than a perverse violation of fundamental principles of police and law, or simply an example of the euphemistic “copspeak” David Correia and I unpack in Police: A Field Guide (Verso, 2018), the celebratory use of Hemingway’s passage might best be understood as an honest admission of what police actually do: hunt, capture, cage, and often kill those non-cop subjects marked as fugitive, unruly, impolite. 3 Angela Davis once referred to police as the “domestic caretakers of violence” and “oppression’s emissaries," and it is worthwhile to consider the predatory animus of this legal violence. 4 A central plot of cop melodrama is a dialectical battle between predator and prey, where police take great enjoyment in the pursuit and domination of another human being. The police protection of private property requires the predatory, and pleasurable, pursuit and capture of poor and racialized species. 5

For starters, there’s nothing unusual about a cop using the Hemingway passage. It is quite common in policing circles. The same passage was popular in 1996 among members of the NYPD’s Street Crime Unit, who three years later would infamously execute Amadou Diallo with a barrage of 41 gunshots while the Guinean immigrant was reaching for his wallet. 6 Police K-9 trainers Tracy Bowling and Jeff Schettler both open their respective manuals on manhunting with the same quotation. Schettler’s “mantracking” company, the Georgia K-9 National Training Center, sells a t-shirt displaying the quotation accompanied by an image of a K-9 “tracker team” in hot pursuit. Apparently, the first batch of shirts sold out rather quickly with approximately 1,000 units purchased. I found shirts just like these, along with related themes, when attending a police K9 industry conference. Similarly, one police merchandise company, Police Blotter, sells t-shirts with the same quotation in blue and white text so the words “hunting armed men” creates an eye-catching representation of the “thin blue line.”

There is no shortage of other examples of police referring to themselves as the supreme hunters of homo criminalis. Bernard Kerik, former NYPD Police Commissioner, once referred to himself as a “hunter of men.” The police lexicon has always been a glossary of hunting terms, with police work routinely described as the tracking, chasing, pursuing, trailing, searching, raiding, netting, trapping, rounding up, catching, and capturing of “bad guys.” The culture industry, from crime shows to Hollywood films and the news media, repeatedly traffics in the political imaginary of police as hunters. The police fashion industry is again instructive for showing just how pervasive the view that police are hunters really is, with t-shirt inscriptions such as “criminal hunting season” and “I hunt the evil you pretend doesn’t exist.” The previously mentioned Schettler sells t-shirts inscribed with “Hunting Man Since 1307,” a reference to the supposed first written record of bloodhounds used to track European fugitives, while conveniently displacing the long history in the Americas of using dogs to hunt chattel slaves and the indigenous. 7 Police K-9 magazines are chock full of manhunting terminology and imagery, and it is in the world of police dogs where the hunt takes on an explicitly carnivorous character, with images of dogs snarling and exposing their piercing teeth. One popular meme showing a cop and his K-9 reads “Go ahead and run. He likes fast food.” Similarly, a bumper sticker found online shows a silhouette of a German shepherd sniffing a trail with the following:

Hunting Permit Issued to:

Police K-9 Unit.

Open season on any human who makes the poor decision to run or hide from law enforcement. No bag limit. Tagging not required. Allowed to hunt day or night 24/7.

But this isn’t just about words. To speak of police as hunters is not to limit ourselves to language or aesthetics. Rather, the language reflects the materiality of police — the concrete social relations of racist state violence and capitalist inequality police help impose on the social world. The language merely helps us understand, as Grégoire Chamayou insists we must, the police institution as “a hunting institution, the state’s arm of pursuit, entrusted by it with tracking, arresting, and imprisoning.” 8 Or as Mark Neocleous puts it, class war has long been waged through predatory police hunts for the idle poor such as vagrants and beggars. 9 This hunting power is manifest in the routine tactics and strategies of police: patrols, searches, stops, investigations, firearms, spotlights, Warrant Squads, K-9 units, wanted posters, databases, CCTV, GPS tracking, predictive algorithms, helicopters, aerial drones. The hunt is mundane, and not merely a spectacle, as a police commentator notes: “Most manhunts are routine police work and garner little public attention.” 10 Now, an empirically minded criminologist would perhaps challenge this claim by pointing to the fact that police spend very little time “fighting crime” and arresting felons. This is certainly true, but it entirely misses the point, which isn’t that hunting is the only police activity but that a cynegetic logic is the lifeblood of police power.

In the article “Catching Bad Guys” published by the website, Police Voice, the author argues that this popular phrase, along with the term “profiling”, are nothing but euphemisms for the hunting of humans. Proudly, the author admits that hunting forms the “basics of police work”, and although reformers continually try to “soften the police image” by reducing the use of military uniforms and equipment, policing is first and foremost a hunt. “Let me be clear,” the writer clarifies, “officers will never cease and desist from being on the hunt. Police departments across the nation…have a job to do and that is hunt down and capture bad guys.” 11 Of course, the bad neighborhoods of so-called ghettos and slums are the hunting grounds where the “bad guys” — a euphemism for the racialized poor — are most routinely spied, profiled, trapped, tracked, captured, beaten, and killed. As a different cop has recognized: “You can’t hunt in nice neighborhoods.” 12 A police captain for Louisiana’s St. Landry parish, with 25-30 armed officers, K-9’s, police SUVs, and prominent leaders of the local Black community behind him, stares into a camera and vows to a local street gang that “You will be hunted. You will be trapped. And if you raise your weapon to a man like me, we will return fire with superior fire.” As images of young Black men scroll across the screen, the captain refers to them as “animals.” Pointing to the Black community leadership presence behind him, he implores his constituency to “Take back your streets. Take back your country. Come forward with information about these heathens that are terrorizing your community.” His revanchist hunt, the captain insists, is not about racism, but about “right and wrong.” 13

For Chamayou, the prerogatives of pursuing, tracking, and capturing eventually came to be monopolized by the administrative, “scientific” police force — thereby codifying cynegetic relations within the institutional structure of police. The criminological enterprise of studying and classifying “criminals” belongs to this hunting logic. For instance, the inventor of police anthropometry, Alphonso Bertillon, referred to police work as a “particular kind of hunting” that not unlike the hunting of animals requires knowledge of natural history. Just as the non-human animal needs to be studied scientifically, Bertillon reasoned, so should police and their ilk study the human animal called “the criminal.” 14 Similarly, in 1910 the administrative law scholar and member of the New York municipal civil service commission, Leonard Felix Fuld, argued that the police officer should study the criminal’s “habits of life, his personal character, and his business methods as carefully as the hunter studies the character and habits of the animal he hunts.” 15 We might even say that much of police manhood comes from white civilizational manliness associated with settler colonial violence, including the hunts for wild animals. Teddy Roosevelt — avid hunter and police administrator — claimed hunting “cultivates that vigorous manliness for the lack of which in a nation, as in an individual, the possession of no other qualities can possibly atone.” Is this civilizational masculinity not compelling a Chicago officer when he explained to investigators in 2016 that cops patrol the city “like it’s a safari”? 16 Is it not out of the predatory nature of policing that the popular online magazine, PoliceOne, encourages officers to take up the hunting of non-human animals because “honing your tactical skills on a hunting trip is an enjoyable way to stay sharp"? The article begins by asking, “What better way to get some quality off-duty trigger (and personal) time than setting out for a hunting trip?” 17

The pleasures of policing, cops seem to be saying, are basically the pleasures of hunting another human being, and it is for this reason police celebrate themselves as hunters, elevating police work above the humdrum routines of paperwork, sitting, and drinking coffee and eating donuts at the local gas station. Chamayou suggests that the guiding principle of the police hunt is not the enforcement of law, but the “thrill” and “love of the hunt.” Simply put: hunting humans is a “rush.” Leopold von Sacher-Masoch referred to police as a “diabolical pleasure”, surmising that “the profession of the police officer” is “the most amusing form, the supreme expression, of hunting.” 18 Here policing is amusement, and it is fun because it is a hunt for another human being. This brings to the surface the ways cruelty operates through police prerogative. This cruel pleasure became hauntingly manifest in a photograph taken in a Chicago police station sometime between 1999 and 2003. Two white police officers restrain a Black man who has been forced to wear deer antlers on his head. Each officer holds a rifle as they lift the man’s head for the camera, while the uniformed officers smile for their “trophy shot” moment. 19 To police, it would seem, is to gain satisfaction and enjoyment — jouissance — in the pursuit of domination in the service of building and maintaining the color lines and property lines of bourgeois order.

Why is the hunt so thrilling for police? Maybe it’s because the hunting of non-human animals can become boring and success rather predictable, whereas the hunt for the fugitive body is fraught with volatile, and unpredictable challenges. The human is most cunning of all animals, so the hunter can quickly become the hunted, the prey becomes the predator. This is the basic grammar of the manhunt, and it so clearly resonates in the most influential of all manhunting stories, Richard Connell’s 1924 short story, "The Most Dangerous Game" (originally published as "The Hounds of Zaroff"). 20 General Zaroff explains to his next prey, Rainsford, that his hunting of animals simply became boring, but “Every day I hunt, and I never grow bored now, for I have a quarry with which I can match my wits.” Zaroff explains that the human animal is “the ideal animal to hunt” because it displays “courage, cunning, and, above all...reason.” To speak of police as a hunt, then, is not simply to speak of the ways police "dehumanize.” It is also to acknowledge how police humanize those being hunted by recognizing in racialized and marginalized subjects a human capacity for reason and calculated disobedience. From the police perspective, to capture prey is to dominate not merely a human animalized or racialized as beast or savage, but a “thinking man” that is full of fugitive reason, calculation, and of course, a desperate desire for freedom.

If police power is a hunting power, this also means that the police relation must always be understood as a relation of domination since there is no hunt without the desire for imposing one’s will against the prey. 21 Police become not merely the “supreme expression of hunting” but ultimately a supreme expression of human mastery over nature and fugitive reason. This doesn’t mean there isn’t effective resistance and insurgency, for fugitivity itself is an exercise in escaping the grasp of political domination 22 — it only means a focus on the police hunt tips us off to the obscene desire of police power; to policing as always striving to be the highest act of domination. In this sense, the hunt has nothing whatsoever to do with serving and protecting, or fighting crime or keeping the peace or whatever cops and their apologists says it is. To call the violence work of police a hunt, with the racialized, surplus poor as the most frequent prey, is to insist that police power is at heart a predatory power always on the prowl. And it is in this predatory movement police and capital are forever partners in crime. Recognizing this obscene desire for domination is a necessary element in disrupting or demystifying not only “copspeak”, but the carnivorous economies 23 of violence and conquest at the heart of settler colonial, capitalist society.

Notes

1. Lichi D'Amelio, "New York cops see us as human prey," Socialist Worker, June 17, 2013. http://socialistworker.org/2013/06/17/nypd-sees-us-as-human-prey

2. For just a glimpse, see Joseph Goldstein, "Testilying by Police: A Stubborn Problem," New York Times, March 28, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/18/nyregion/testilying-police-perjury-new-york.html

3. Grégoire Chamayou, Manhunts: A Philosophical History. Trans. Steve Rendall (Princeton University Press, 2012.)

4. Angela Y. Davis, If They Come in the Morning …Voices of Resistance (Verso Books, 2016)

5. Relatedly, see Che Gossett’s discussion on blackness, violence, and species, "Blackness, Animality, and the Unsovereign," Verso Blog. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/2228-che-gossett-blackness-animality-and-the-unsovereign

6. Ibid, D’Amelio, "New York cops see us as human prey," 2013

7. 1307 is a reference to the year stories apparently first emerged depicting Sleuth Hounds hunting humans, specifically in Scotland. For examples on the use of dogs in slavery and conquest, see for instance, Sara E Johnson, "'You Should Give them Blacks to Eat': Waging Inter-American Wars of Torture and Terror," American Quarterly, 61(1): 65-92; also Walter Johnson, Rivers of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom, (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013); John Grier Varner and Jeanette Johnson Varner, Dogs of Conquest (University of Oklahoma Press, 1983).

8. Quoted in Chamayou, p. 89.

9. Mark Neocleous, "The Dream of Pacification: Accumulation, Class War, and the Hunt," Socialist Studies/Études Socialistes, 9(2): 7-31.

10. Robert O'Brien, "Police Manhunts," Police: The Law Enforcement Magazine, March 18, 2009. http://www.policemag.com/blog/swat/story/2009/03/police-manhunts.aspx

11. "Catching Bad Guys," Police Voice: The Voice for Law Enforcement, January 28, 2016. http://policevoice.com/catching-bad-guys/

12. Lori Beth Way and Ryan Patten, Hunting for “Dirtbags”: Why Cops Over-Police the Poor and Racial Minorities (Northeastern University Press, 2013).

13. See the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KjtGkrxnKA8

14. Quoted in Chamayou

15. Leonhard Felix Fuld, Police Administration: A Critical Study of Police Organizations in the United States and Abroad (G.P. Putnam Son’s, 1910) P. 151. https://archive.org/details/policeadministra00fuldrich

16. German Lopez, "Report: Chicago police use excessive force and often treat people 'as animals or subhuman,' Vox, Jan. 13, 2017. https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/1/13/14265666/chicago-police-justice-department-investigation

17. Megan Wells, "7 tips to prepare for an epic hunting experience," PoliceOne.com, Aug 16, 2016. https://www.policeone.com/off-duty/articles/210783006-7-tips-to-prepare-for-an-epic-hunting-experience

18. Quoted in Chamayou, p. 87.

19. For an insightful discussion of this and the general practice of police “trophy shots”, see Travis Linnemann, "Proof of death: Police power and the visual economies of seizure, accumulation and trophy," Theoretical Criminology, 21(1): 57–77.

20. To read the story: https://archive.org/stream/TheMostDangerousGame_129/danger.txt

21. This is a key point of Chamayou’s argument.

22. See for instance, Neil Roberts, Freedom as Marronage (University of Chicago Press, 2015); Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Minor Compositions, 2013).

23. I take the phrase “carnivorous economies” from James Baldwin, "An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis," The New York Review of Books, January 7, 1971. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1971/01/07/an-open-letter-to-my-sister-miss-angela-davis/

Tyler Wall is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Tennessee.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]