After Saleh

Ali Abdullah Saleh is dead, but his politics are very much alive in Yemen.

Ali Abdullah Saleh was shot dead by Houthi militants on December 4, following his very public break with former allies, and days of fighting in Yemen’s capital city of Sana’a. Shortly after the news broke, a video of Houthi fighters carrying Saleh’s bloody corpse coursed through the Internet, shocking observers who had come to regard him as indestructible, after forty years of dictatorship and his cunning survival of Arab Spring protests that hit the country. Although Saleh’s killing wasn’t surprising — he had fought the Houthis for seven years prior to the 2011 uprising — it still marks a bloody shift in the civil war. The country’s violence has gone largely unnoticed, but the tensions behind it have been building for decades.

Saleh’s death is best understood as a consequence of his style of politics, which ended violently because of the complex institutions that have sustained it since the 1970s. It is likely that as the Houthis consolidate power, they will extend that violence even further, and will be mirrored by the moves of other elite actors in the conflict. Furthermore, Saleh’s execution needs to be understood in relation to the frustrated ambitions of global powers like the United States, and the GCC-led coalition it primarily supports through Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Indeed, Saleh’s attempted “uprising” seems to have been part of a broader attempt to end the war on relatively clean terms, and now that it has failed, things are likely to worsen considerably.

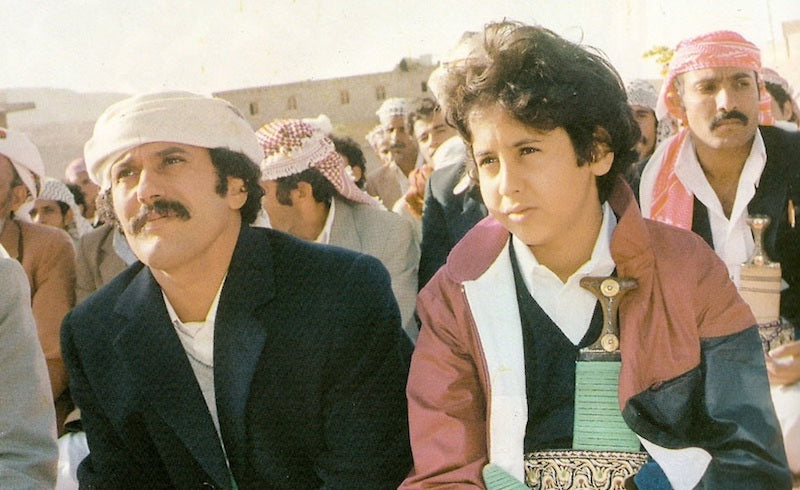

Saleh was the protégé of Colonel Ahmad Husayn al-Ghashmi, and supported a military coup in North Yemen in 1974, leading to his appointment as military commander of Ta’iz province in 1975. Following a string of assassinations, including that of his mentor, Saleh took power in 1978. Though he was not expected to last long, Saleh defied predictions and built a durable regime through strong informal networks with tribal and business elites, as well as clever international allegiances. He called this process “dancing on the heads of snakes,” due to the challenge of negotiating power with powerful actors directly, rather than engaging with them through state institutions like a civil service. Saleh has been rightly criticised for this approach, which effectively turned the country into a fiefdom.

It has been clear for decades that Saleh was stifling the country’s potential, both economically and in terms of democratic politics. Yemen has been the poorest country in the Arab world for decades, known for its low life expectancy, high levels of illiteracy (particularly among women), weak economic indicators, and alarmingly high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition. Since Yemeni society is largely governed by informal relationships between the country’s elites, rather than effective state institutions, it has been almost impossible to carry out basic development initiatives, such as diversifying the economy, growing crops other than qat, and attracting foreign investment. These problems have been particularly damaging in rural areas, which rely heavily on male urban labour and remittances from Yemenis working abroad, as well as in the formerly socialist south. Following unification in May 1990, southern Yemen found itself at the mercy of Saleh’s infamous cronyism and northern domination of important institutions like universities, parliament, and the oil industry, briefly leading to a 1994 civil war that ended up intensifying inequalities.

Yet although Saleh preferred establishing power through informal ties, and a decentralised state that relied on him and his family by design, that doesn’t mean there was an absence of violence. Saleh was not unique in imposing stability through brutality; cynically using Sunni Islamist cultural politics to divide the population (particularly when it came to gender roles), and terrorising his democratic opposition through organs like the Political Security Organisation. Washington’s influence was visible in the latter, with the United States playing a massive role in the creation of the National Security Bureau in 2002. Drone strikes began that same year, reflecting how Western intelligence agencies and special forces were cooperating with Saleh’s dictatorship in order to widen their own footprint in the country. Additionally, Saleh was constrained by the fact that since the 1962 North Yemeni Revolution, Yemen’s tribes had become modern (and heavily armed) political actors that fought for their interests within the state. As a result, he could not simply use a carrot and stick approach, and had to balance armed response with complex dealmaking. Typically for the region, although he technically broke with the colonial era, he tried to keep some of its core aspects in the new framework.

The result was an approach in which Saleh tried to use state violence sparingly, and in most cases, allowed nominally independent elite actors to police the country by carrying out violence on their own. This process is most clearly illustrated when it comes to gender policing. Individual men were empowered to do the most intense work by themselves, and often against women in their own families, without requiring the state to ever give them a salary or win them over politically. Saleh exploited Islamist anxieties about women dressing too provocatively and moving around too freely in public to extend the government’s reach into city streets, workplaces, and nearly every household, without needing to do much of anything. He understood that his grip on power did not actually require a strong state. Rather, his authority was successfully projected through other people in a decentralised manner.

One of the consequences of this approach was that even armed groups fighting against the state, such as the Houthis during the Sa’ada War and revolutionary jihadist groups like Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and Islamic State in Yemen, inevitably picked up certain impulses from Saleh. Indeed, it’s hard not to think of the man when watching the Houthis crack down on Sana’a by shutting off internet access, moving against Saleh loyalists, raiding the homes of accused dissenters, detaining hundreds without charge, and exploiting material deprivation to solidify their rule through severe psychological distress. The most bloody excesses of the civil war need to be understood within this reality. Saleh is dead, with his corpse paraded out in front of cameras, but his politics are very much alive.

Even overlooking its impact on democratic activists and local residents, the Houthis’ rapid consolidation of power is a disaster for the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and U.A.E. As the group tries to turn northern Yemen into a tribal-based theocracy, bolstered in its efforts by a spike in sectarianism in cities liberated by coalition forces, its international opponents are now facing a situation where they will be unable to carry out their original plans for ending the conflict.

It is easy to lose track of this with almost daily reports of civilian casualties from bombing runs, but the war is going very poorly for the coalition. Originally, it planned to use the spectre of Iranian links to the Houthis (which have been hugely exaggerated, though they may exist now as a result of the fighting) in order to justify a foreign intervention that would neutralise revolutionary unrest. The argument that Iran uses the Houthis as a “Yemeni Hezbollah” has allowed for bloody colonial disciplining in the country, whether through the US-Saudi bombing campaign, or recent attempts to choke the country with a coalition blockade. However, the Houthis have continued to hold onto Sana’a, and the war’s front lines have not shifted much since late 2016, though Riyadh recently found itself within range of an enemy missile.

It is likely that Saleh’s attempted “revolution” against the Houthis was spurred on by external actors, who in the context of a deteriorating war effort, sought to neatly divide the country among pliable allies in order to begin withdrawing their forces. If Saleh had succeeded in expelling the Houthis from Sana’a, then it would have allowed coalition forces to enter the city, and drive the group back into the mountains. Saleh himself would have then been restored to a prominent position, with either his son or Al-Islah (a former Muslim Brotherhood affiliate that has strengthened ties with the coalition) positioned to succeed him.

The relative stability would have given Saudi Arabia a chance to withdraw, strengthening the position of Crown Prince Muhammad Bin Salman. While the war in Yemen initially allowed his government to assume a more powerful posture and push major Thatcherite reforms, it has since become much more trouble than it’s worth. Expectations of a speedy victory proved naive and the conflict is now greatly destabilising the kingdom, especially as the death toll increases. North Yemen would have been handed over to leaders with friendly ties to Saudi Arabia, allowing it to get out.

The United Arab Emirates has been more ambitious, going so far as to prevent former president Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, an ally of Riyadh who won an election in which he was the only candidate, from landing in the temporary capital of Aden. It has formed its own alliances, and built stronger ties with southern secessionists under Aidarous al-Zubaidi. The U.A.E. would have tried to carve out South Yemen, leaving the north as a theocratic satellite state of Saudi Arabia. Much of its former socialist leadership would have been restored (without the socialism), with the vast desert province of Hadhramout possibly gaining its independence as well. The new countries would have been firmly in the Emirati sphere, giving Abu Dhabi a chance to expand its holdings in the Indian Ocean, possibly leading to a 21st century version of the Omani Empire that would have eventually replaced Saudi Arabia as a major regional power.

It would have been neat and simple. Unfortunately, the Houthis defied expectations, and killed Saleh a few days after the plans were set in motion. Although the Emiratis’ position is still relatively strong, given that the southern resistance is currently the best equipped faction engaging the Houthis on the ground, the Saudis are running out of options. They are increasingly isolated, even drawing a rebuke from the Trump White House last month, stuck with Hadi, who has little support on the ground regardless of his international legitimacy, and divisions between opposition parties and militias continue to work to the Houthis’ advantage. It increasingly seems likely, particularly after Saleh’s death, that in addition to Yemen collapsing under the weight of this conflict, Saudi Arabia will suffer serious collateral damage.

Bilal Zenab Ahmed is an MPhil/PhD student at SOAS, University of London, studying how Islamists politicise the human body in Pakistan. They are formerly the Associate Editor of Souciant.com, and currently based in London, working as a freelance writer. You can find them on Twitter at @pakistanarchy and on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/pakistanarchy

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]