No professional will ever make the revolution

No past revolution, she says, can be attributed to professional revolutionaries. Usually it was the other way around: “revolution broke out and liberated, as it were, the professional revolutionaries from wherever they happened to be – from jail, or from the coffee house, or from the library.”

Five great amateurs whose work changed the world, from author of The Amateur, Andy Merrifield.

The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love is 40% off, included free bundled ebook, until Sunday, June 18 at midnight UTC. Click here to access the discount.

Five great amateurs whose work changed the world, from author of The Amateur, Andy Merrifield.

The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love is 40% off, including free bundled ebook, until Sunday, June 18 at midnight UTC. Click here to access the discount.

Professionals are everywhere. Little gets done nowadays without a professional “expert” offering their specially acquired knowledge: downscaling and evaluating, measuring and advising, scheming and sorting out life for millions of people.

Our lives have fallen into the hands of box tickers, bean counters and pedants. Where are the independent thinkers, wayward poets, dabblers and square pegs who can challenge this accepted wisdom? And I’m not talking about Donald Trump.

Here are a few iconoclasts who still inspire, who thought the unthinkable, and changed the world.

Karl Marx was an outsider and autodidact in economic affairs. Unaffiliated and frequently destitute, he sat alone in the Reading Room of the British Museum teaching himself political economy, scribbling away at his magnum opus, Das Kapital. He had no professional badge of credibility to invoke. His was no economic “science” in the professional sense of the term. He was adept at critiquing ruling class knowledge, a foreigner, a jobless amateur easily dismissible by the professional powers-that-be.

Marx exposed Professor Nassau W. Senior’s infamous “Last Hour” as apologist ideology. With Senior, Marx said, Oxbridge credentials are mobilised to legitimise both flimsy scholarship and the time-served links between the academy and business. Senior was summoned to Manchester, the seat of the international textile trade, to do battle for the manufacturers. He was their chosen “prize-fighter”; his economic science was ammunition to defeat struggles to reduce the factory working day.

Senior went to enormous lengths, Marx said, invoking much numerical data, to support his industrial patrons, arguing that if the working day was reduced from twelve to ten hours all the manufacturers’ profit would be destroyed. It would likewise destroy the workers’ livelihoods, because along with profits, money for wages would go, too. Everybody would apparently lose out. In the eleventh hour, the worker reproduced their wages, and in the twelfth – the so-called “Last Hour” – the manufacturers’ profit. To cut the working day to ten hours would thus eliminate both. As Marx exclaimed, “and the Professor calls this ‘analysis!’”

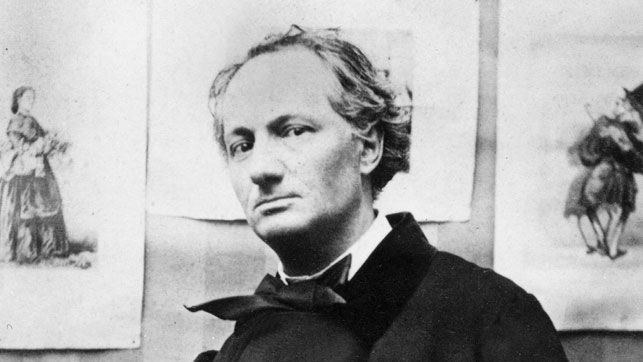

Charles Baudelaire didn’t consider poetry a job, even if sometimes he got paid to pen it. He’d have gladly done it for nothing, and frequently did do it for nothing. When he wasn’t crafting romantic verse, Baudelaire produced great art criticism. One of his best essays, “The Painter of Modern Life,” from 1863, was about Constantin Guys.

Guys wasn’t just a painter, Baudelaire says, whose “conversations are limited to the narrowest of circles.” Guys was something more: “a man of the world,” a “world-minded” person, “a spiritual citizen of the universe.” Eat your heart out Theresa May. Guys detests the label “artist,” hates to be tied down to an expertise. He wants to know everything, understand everything, appreciate all that happens on planet Earth, depict it in paint, in pencil and charcoal, in watercolours.

Guys, like Baudelaire, sought out the unknown, “the inestimable value of novelty.” Curiosity, for both, became “a compelling, irresistible passion”; not about offering answers, or preaching sure truths, pontificating expertly, so much as asking questions, wondering why and how come. It’s more like a “return to childhood,” Baudelaire says, seeing everything once more as an infant sees, as we all once saw: with freshness, and a perception that is “acute and magical.”

Spiritual citizens of the universe celebrate inquisitive learning, the adventure of not knowing what you’re doing, of zigzagging and fumbling around a subject until you master it. That’s the real route to Baudelairean expertise: a process lasting a lifetime, not a product bought at a training course. Baudelaire invites us to join him on a voyage for personal authenticity, a quest to tell the truth about ourselves in a society that rewards us for telling lies, for playing its game.

Jane Jacobs was our greatest amateur prophet of the city, standing up to our greatest urban professional, Robert Moses. In Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), she wrote lovingly and compellingly about our city streets, even while fiercely denouncing the urban experts who towered over her. They saw nothing but statistics, people as abstractions uprooted on the basis of mathematical averages. With her catalogue of workaday street blocks, Jacobs offered another vision of the city that let ordinary citizens recognise themselves as city makers, not simply city users, and see their real place in urban life, perhaps for the first time.

She wrote without any credentials, critics said, without formal architectural or planning training, without a university degree. And yet, hers was a refreshing counter-narrative on the page, practiced out in public. When Robert Moses planned a huge swath through lower Manhattan, yet another giant road, the multi-storey Lower Manhattan Expressway, razing vibrant communities in Greenwich Village and SoHo, Jacobs and her fellow residents mobilised to “KILL THE XPRESSWAY NOW!” She was arrested for inciting a riot. But Jacobs knew how to defend herself, how to organise, how to get publicity, how to form coalitions with other amateurs.

Moses decried his antagonists: “There’s nobody against this – nobody, nobody, nobody, but a bunch of, a bunch of mothers!” At a hearing at the New York City Board of Estimate, Jacobs and fellow citizens ventured across the stage to get an audience with the bigwig professionals sat above. “And this threw them into the most incredible tizzy,” she recalled, “the idea of unarmed, perfectly gentle human beings just coming up and getting in close contact with them. You never saw people so frightened.”

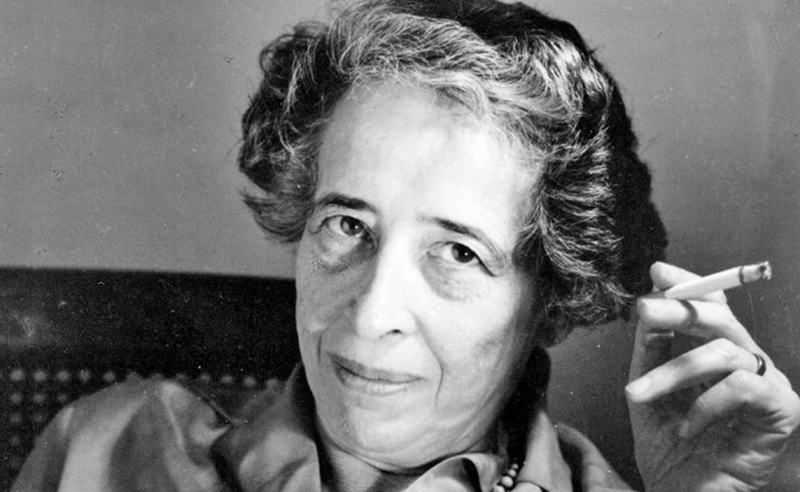

Hannah Arendt was Jacobs’s contemporary, a trained philosopher, a former student of Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers. Yet as an émigré Jew who fled her native Germany in the 1940s, she reinvented herself in Anglophone New York. She learned to write, painstakingly, in English, and penned detailed thought-pieces for non-specialist audiences – introducing Walter Benjamin to America and reporting from Jerusalem on the Adolf Eichmann trial, both for the New Yorker. Arendt championed big, heterodox ideas, strayed across disciplines and was an irreverent independent, a public intellectual always in exile. She never lost a feeling of “distance” from the English language, nor did she ever see political theory as any “profession.”

In On Revolution, published in 1963, Arendt unearths the amateur revolution. Amateurs didn’t only organise the city in times of revolutionary upheaval, she said, like in the 1871 Paris Commune: amateurs were also the principal instigators. Amateurs in revolt literally made the revolution, and, who knows, may still make the revolution again. Closer examination of revolutionary history reveals how amateurs were behind what Arendt calls the “lost treasures of the revolutionary tradition”: the popular councils, those spontaneously cohering organs made up of ordinary people, outside of revolutionary parties.

Arendt’s point is a populist one: no professional, not even a professional revolutionary, made or will ever make the revolution. No past revolution, she says, can be attributed to professional revolutionaries. Usually it was the other way around: “revolution broke out and liberated, as it were, the professional revolutionaries from wherever they happened to be – from jail, or from the coffee house, or from the library.” Not even Lenin’s party of professional revolutionaries would ever have been able to make a revolution; “the best they could do was to be around, or to hurry home, at the right moment, at the moment of collapse.”

Edward Said was a renowned professor of comparative literature at Columbia University, an Arab-American who spoke out against American foreign policy and its support for Israel, a tireless advocate of Palestinian rights.

In 1993, he presented his BBC Radio 4 Reith Lectures on “Representations of the Intellectual.” Said was appealing here to intellectuals – and budding intellectuals – to reflect upon their craft and political engagement. Expertise, he said, goes beyond competence, of being conscientious about what you do, and having the right skills to do it. Rather, Said stressed the importance of making choices. He asked what was for sale, whether the goals you set yourself with your expertise were conformist or critical, and, perhaps most importantly, in whose interests were you acting?

“The particular threat to the intellectual today,” Said reckoned, “is an attitude I call professionalism.” Professionalism “means thinking of your work as an intellectual as something you do for a living, with one eye on the clock, and another cocked at what is considered to be proper, professional behaviour – not rocking the boat, not straying outside the accepted paradigms or limits, making yourself marketable and above all presentable.”

All of which can, and indeed should, be countered by courageous intellectual amateurism. Anybody can do it – even professionals. Above all, it means a readiness to withstand comfortable and lucrative conformity, a desire “to be moved not by profit or reward but by love for and unquenchable interest in the larger picture, in making connections across lines and barriers, in refusing to be tied down to a specialty, in caring for ideas and values in spite of the restrictions of a profession.”

An intellectual ought to be someone who raises questions at the very heart of professionalised activity. It’s a sense of self-worth, Said reckons, an affirmation of engaged activity that hinges on an audience. Indeed, is that audience there to be satisfied, a client to be kept happy? Or is it there to be challenged, provoked, mobilised into collective, democratic action?