Decolonising Desire: The Politics of Love

Dalia Gebrial examines the colonial scripts that encode people in and out of the possibility of love. Embedded within the constituent discourses of love – of desirability, emotional labour, support and commitment – are codes of social value assigned to certain bodies; of who is worthy of love’s work. The labour of decolonising these representative paradigms is structural, and involves addressing their material histories.

“The oriental woman is no more than a machine: she makes no distinction between one man and another. Smoking, going to the baths, painting her eyelids and drinking coffee — such is the circle of occupations within which her existence is confined….What makes this woman, in a sense, so poetic, is that she relapses into the state of nature”

Gustave Flaubert on Egyptian women“I’m so obsessed I want to skin you and wear you like Versace”

Katy Perry, referring to Japanese people in an interview with Jimmy Fallon“Today, I believe in the possibility of love; that is why I endeavour to trace its imperfections, its perversions”

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin White Masks

What does it mean to be lovable? Who is and is not deserving of particular kinds of love? How is love coded and reproduced? What, and who, is absent when love is represented?

There is a slowly growing body of work exploring what Averil Clarke calls the ‘inequalities of love.’ In her book, Clarke uses national survey data and ethnographic interviews to explore the unique difficulties faced by university-educated black women when seeking romance and marriage, as compared to their white and Hispanic counterparts. In 2014, OkCupid released data demonstrating how ‘response rate’ to dating profiles is profoundly affected by how you are racialised. There is a plethora of blogs and think pieces – particularly by women of colour – documenting traumatic and degrading experiences during dating and sex that specifically happens through and alongside their racialisation. Writer Junot Diaz – credited with coining the loosely defined term ‘decolonial love’ – explores in his novel Monstro the dynamics of a half-Dominican half-Haitian girl’s “search for – yes – love in a world that has made it a solemn duty to guarantee that poor raced girls like her are never loved.” Of course, getting attention on a dating website – or being married – is not an indicator of being loved. However, what this body of data and personal narrative tells us is that race profoundly structures your experience of desire, commitment and respect.

—OkCupid dating research, 2014

—OkCupid dating research, 2014

The primary social practice of love has been through heteronormative, monogamous dating and marriage; there is a compelling and important radical argument that these relationship structures are oppressive and predicated on the uneven and gendered distribution of emotional labour. What I’m interested in is further investigating is what it means to not be legible within even these problematic discourses of love. Exclusion from such frameworks is not always tantamount to liberation – in fact, exclusion denotes an entirely different set of racialised oppressions.

Looking back at my own experience, a nascent adolescent sexual curiosity was rapidly crushed by a combination of bodily mockery and – most often – total invisibility. A series of small lessons learned through film, television and personal experience, accumulated to the eventual understanding that people who look like me cannot be the subject of love. If lucky, we can be objects of fetishisation – but that is very different to being perceived as lovable.

What is often missing from accounts of the racial dynamics of ‘love’ and being ‘loved’ is an understanding of where these codes – of who can be loved, who cannot be loved and whose love matters – come from. Why do we have such a robust and universally understood racial grammar of desire, to the point where porn is literally categorised according to racist tropes?

In her essay on colonial sexual politics, Sandra Ponzenesi explores how the twin, sexualised images of the harem and the Hottentot framed almost all representations of women of Africa and ‘the Orient’ (the modern-day Middle East) in 19th century European art and literature. Within these colonial scripts we can find many of the origin stories of contemporary racial grammars and start to unpack the power relations they reproduce. Most importantly, we can build an understanding of how ‘love’, represented as an apolitical, transcendent realm of affect into which you unwittingly fall, is actually deeply politicized, and linked to broader structural violences faced particularly by women of colour globally.

—In the Harem by Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1904)

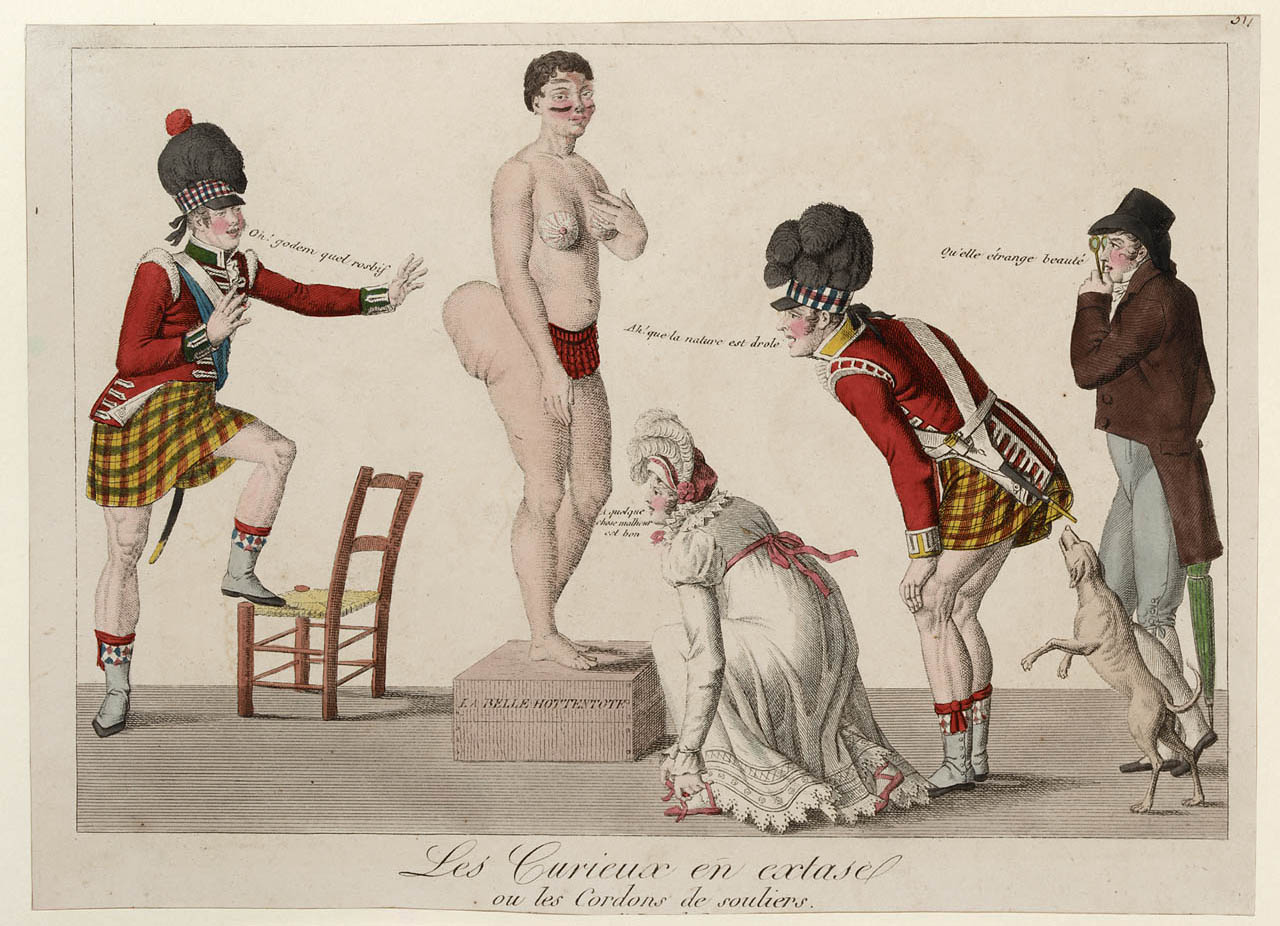

Embedded within the constituent discourses of love – of desirability, emotional labour, support and commitment – are codes of social value assigned to certain bodies; of who is worthy of love’s work. The Hottentot and the harem in Ponzanesi’s essay are quite different paradigms of the desiring gaze. The harem is marked by often multiple brown women’s bodies viewed through a voyeuristic eye; tension is created through the intimation that their potent sexuality is “under lock and key” – their bodies are often loosely clothed, and it is implied they are unaware they are being watched. Erotic thrill is generated through the tantalising possibility of possession. In contrast, representations of the Hottentot woman provide a paragon of objectification: the focus is on the minute, invasive and dehumanising details of an individual woman’s body. The archetypal narrative of the Hottentot is of course the case of Saartjie Baartman, a South African Khoikhoi woman, whose body was toured around 19th Century European circuses; her particular body shape put forward as representing the ‘essence’ of all African women, and as an object of sick European fascination. Even in her death she was not spared the racialised misogyny of the European gaze; her brain, skeleton and sexual organs remained on display in a Paris museum until 1974, more than 150 years after her death in 1815.

—Les Curieux en Extase by Louis Francois Charon (1815)

What connects these two paradigms is the total reduction of personhood to corporeality. The Hottentot is a silent, static image, presented from the pages of eugenics diagrams or from the pedestal of an exhibition. As for the harem’s brown women – their bodies become sites of exploration and self-discovery; props signifying adventure and domination within colonial narratives. Edward Said’s brilliant, gut-wrenching reflection on Flaubert’s encounters with Egyptian courtesan Kuchuk Hanem – “a widely influential model of the Oriental woman” – cannot be improved upon:

She never spoke of herself, she never represented her emotions, presence or history. He spoke for her and represented her…. The Oriental woman is an occasion and an opportunity for Flaubert’s musings; he is entranced by her self-sufficiency, by her emotional carelessness, and also by what, lying next to him, she allows him to think.

The European attraction to the colonised bodies of the harem woman and the Hottentot was paradoxically underscored by revulsion. The Hottentot – a hallmark image of 19th Century eugenics – was continually associated in both art and medical literature with unbridled, pathologised sexuality. Diagrams of African women’s vulvas were preoccupied with what was perceived to be an ‘overdevelopment’ of the clitoris and labia. This was portrayed as a signifier of a biologically determined sexual excess ‘proving’ their pathological and animalistic nature. Such scientific racism toward African women was constituted almost entirely through and alongside portrayals of their sexuality and sexual organs in a way that was not the case for African men. Similarly in Flaubert’s portrayals of the harem, the Oriental woman’s ‘machine-like’ sexuality aligns her with primitivism; he speaks of the “nauseating odour” of the bed bugs that surround her and how her sexuality “relapses [her] into a state of nature.”

The Hottentot archetype of late 17th Century European colonial discourse was easily adaptable to the racist ideology and specific material needs of chattel slavery in the Americas, which required an abundant, constantly growing labour force. Black women and black men were both perceived and treated as sub-human commodities, and in women, this was specifically constituted through ideas around their reproductive capacity to provide offspring that could be sold for the slaveowner’s profit. Enslaved African women were routinely raped by crew members on the transatlantic voyage to the Americas. Once on the auction block, the reproductive and sexual features of women slaves were inspected for signs of being good ‘breeders,’ and forced ‘breeding’ with male slaves was not uncommon.

This mode of dehumanization within an institutional pattern of rape was mirrored in the broader, systematic treatment of their bodies. During slavery, the rape of black women – like native women – was not legally recognised: while white women struggled to bring proof violation of extra-marital consent, women of colour were unable to get a foot into the courtroom. After abolition, these legacies continued – particularly in the South. Whilst black men were being brutalised and criminalised in the name of defending white womanhood, black women continued to struggle to have sexual violence committed against them – particularly by white men – recognised as violence. The construction of black womanhood as animalistic, hypersexualised commodities made them situated them outside any discourse of consent or sexual agency, and excused the lack of legal and social support provided for African American assault survivors.

—Three Young White Men and a Black Woman by Christiaen van Couwenbergh (1632)

The construction of the racialised woman’s body during colonisation and slavery as dirty, hypersexual and close to nature was specifically through their opposition to the chaste cleanliness of the Victorian woman, who, for her part, was bound to domesticity. As bell hooks writes in Ain’t I a Woman:

The shift away from the image of white woman as sinful and sexual to that of white woman as virtuous lady occurred at the same time as mass sexual exploitation of enslaved black women - just as the rigid morality of Victorian England created a society in which the extolling of woman as mother and helpmeet occurred at the same time as the formation of a mass underworld of prostitution.

Indeed, representations of other marginalised women – such as sex workers and queer women – were constituted across similar lines. A gynaecology handbook by 19th Century surgeon Theodor Bilroth connected the stereotypical hypersexuality of African women to “those excesses” which are “called lesbian love.” Similarly, as Sander Gilman notes in her excellent Black Bodies, White Bodies, becoming a sex worker was seen as biologically determined: a particular set of physiological traits confirmed inherent hypersexuality, which drew women towards sex work. The existence of sex workers in turn was seen as a public health issue, likened to pollution in the streets of the city. What connects these highly embodied categories of undesirable women is that they are specifically constructed in opposition to the discourses of love, romance, marriage and family. Their bodies are fascinations, adventures, scandals and pathologies – these subjects are not worth even the premise of the emotional labour of commitment.

The sexual deviancy and moral downfall of white women was often indicated by proximity to black and brown bodies in representations of European women from as far back as the eighteenth century; this was a central function of bodies of colour in art. Gilman refers to the famous Edouard Manet painting Olympia (1865) – depicting a nude white woman reclining on a bed, attended by a black servant – as an archetype of this trope. The painting caused moral outrage upon its exhibition, because a series of signifiers, including the presence of a black body, indicated that it was depicting an illicit context in a way that nude paintings of the era otherwise did not.

—Olympia by Edouard Manet (1865)

—Olympia by Edouard Manet (1865)

Today, the legacies of these colonial scripts have adapted magnificently to contemporary culture – and television, film and music videos allow for their wider dissemination, particularly in the West. Even when cloaked in the premise of affection, the language with which we speak about desire is entrenched in racialised instrumentalisation. Indeed, how different is David Bowie’s ode to his ‘China Girl’ – “I could escape this feeling with my China Girl/ I feel a wreck without my little China Girl” – to Flaubert’s musings on the “occasion and opportunity” of Kuchuk Hanem's body and what, lying next to him, it “allows him to think”? Similarly, ‘feminist’ justifications for the Iraq War were cloaked in the language of love and solidarity for a voiceless brown woman who – like Kuchuk Hanem – “never represented her emotions, presence or history.”

In one of the more well-known instances, pop star Miley Cyrus’ attempts to repackage herself from cute, infantile Disney do-gooder to edgy, grown-up provocateur involved highly strategic image changes: sexier clothes, sexier lyrics and – in a tale as old as Empire – the use of black women dancers. When pointed out to her that this could be viewed as instrumentalisation, I don’t doubt she was authentically shocked: “those aren’t my accessories. They’re my homies!” Within her conceptual framework, this is what it means to express ‘love’ for black women.

—Miley Cyrus performing at the 2013 VMAs

So where to go from here? When it comes to envisioning a ‘decolonial love,’ a checklist behavioural guide for relationship etiquette is not sufficient. The problems of dehumanisation and fetishisation did not begin in individual relationships – they just come particularly to light within romantic or sexualised contexts – and will not end there. They began in a system of representation borne out of a power relation; a relation that existed for the purpose of material exploitation and resource extraction. Later, immigration policies, labour practices and distribution of resources would also feed into this racialised hierarchy of desire. The labour of decolonising these representative paradigms is structural, and involves addressing their material histories. To believe – as Fanon says – in the possibility of love, we must comprehend the fact that we do not obliviously fall into it, but are coded in and out of it, and that this has implications beyond our individualised experiences.

Dalia Gebrial is campaigns co-ordinator for the Undoing Borders campaign and a freelance writer. She is currently editing a special issue of Historical Materialism on 'Identity Politics,' and working on an edited volume on decolonisation in higher education.

This excerpt is part of a series of essays for Valentine's week, looking at love, desire and relationships at the intersection of capitalism, the state, and politics. Read everything here.