Books of the Year 2012: Chosen by Verso

In between publishing the works of Žižek and plotting ways to destroy capitalism, many of us at Verso occasionally like to read books.

As usual we were stunned by how little the newspaper's books of the year seemed to represent our own reading so we gathered together our own top books of 2012 (and beyond) and the resulting list is a refreshing reminder of just how lively much of the independent publishing scene is.

What We Are Fighting For by Federico Campagna and Emanuele Campiglio. Pluto Press.

A much needed series of manifestos for a new world, featuring such authors as Nina Power, Mark Fisher, David Graeber and Bifo.

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz. Faber & Faber.

The short story follow up to his Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Ostensibly a guide to relationships drawn from trials and travails of the heart, the many different characters of the book are also all part of the Dominican Republic diaspora searching for a better life in the United States. Hard though they try, no one can ever quite escape their familial, emotional or cultural roots. Throughout Diaz smatters the book with colloquial Spanish, sharply drawn characters and genuinely moving or memorable stories, as well as sideways but perceptive glances at immigrant life.

Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle by Silvia Federici. PM Press.

It’s been an absurd length of time since Silvia Federici has published and her plenary talk at this year’s HM conference in London shows why her perspective has been so influential. So it was great to see a new collection of her essays.

Hawthorn & Child by Keith Ridgway. Granta.

A crime novel by the author of Animals is not going to follow convention. The first of these detachable fictions lures you into believing that you know what will happen, but you never will. Wolf packs, Rothko and Tony Blair all somehow connected by two shadowy detectives. The writing is sparse and chilly, but in between the lines are elements of disarming warmth and feeling. Goo Book will break your heart. An excellent companion piece is The Spectacular, a short story for the Kindle.

The Culture of Narcissism by Christopher Lasch. W. W. Norton.

We were intrigued by the return to Christopher Lasch in Chris Hayes’ The Age of Illusion and we were sent back to our dusty copy of his Culture of Narcissism.

Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in Modern Horror Film by Carol J. Clover

Though dating back to 1992, Carol Clover's incisive account of that oft-maligned genre, the horror movie, is still relevant and woefully under-discussed. Horror movies, and in particular, 80s slashers, often fall to charges of misogyny, not least for their depictions of teenage girls’ brutal deaths (notoriously occurring as unspoken comeuppance for premarital, underage sex). But, as Clover elucidates in her study, there also exist possibilities for gender identity disruption in a genre which singularly allows male viewers to identify with primarily female victim-heroes. A fascinating account of spectatorship and the politics of representation within "lowbrow" filmic endeavors.

Dead Man Working by Carl Cederström & Peter Fleming. Zero.

A grim but compelling tour through the modern mode of work.

Heroines by Kate Zambreno. MIT Press.

An exceptional work of literary scholarship, Zambreno's book expands the theme of her influential blog, Frances Farmer is My Sister that gave recognition to the Modernist wives who were often seen as little more than voiceless muses. This work puts the personal back into criticism because as Zambreno excellently puts it, "pretending an objectivity where there is nothing objective about the experience of confronting and engaging with and swooning over literature."

Behind the Beautiful Forevers by Katherine Boo. Portobello.

2012 has been a great year for narrative non-ficiton. Reading this book in Mumbai is an experience. The book is an account of a small community in a squatters’ settlement on the edge of the airport, a region that is at the centre of the debate of what to do with the historic slums, home to nearly 60% of the city's population. It is a heart-breaking story that cuts across the standard economist's arguments about Dharavi and other fragile neighbourhoods.

The Body of Il Duce: Mussolini's Corpse and the Fortunes of Italy by Sergio Luzzatto. OWL BOOKS.

One of the most interesting books we read this year. A popular biopolitical history, Luzzato traces the popular reaction to the fascist regime, through literature and journalism of the time, by examining attitudes towards Mussolini's body. Whilst alive, his living flesh was haunted in the popular imagination by the corpse of socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti, whose brutal murder he was accused of masterminding. After his execution by partisans, Mussolini's own body was mutilated and hung before crowds in Milan's Piazzale Loreto, the scene of a grim earlier public display of the bodies of anti-fascists. The corpse of Il Duce then became the subject of a macabre cat-and-mouse game, first being buried in an unmarked grave before being kidnapped in 1947 by neo-fascists. Recaptured by the state a year later, the body was kept in a limbo for over a decade before being returned to his family and buried in his family crypt in Predappio.

“Left Wing Melancholy” from Selected Writings, Volume 2: Part 2 by Walter Benjamin. Harvard.

Working on Jodi Dean’s The Communist Horizon reminded us of this extraordinary essay, so of course we had to shell out for the second volume of the superb Selected Writings.

Dogma by Lars Iyer. Melville House.

A wickedly funny satire of today’s modernist melancholic. We’re looking forward to the third volume due early next year.

Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. Northwestern University Press.

Battling against the cul de sac of these wannabe mittel European’s Craig Dworkin and Ken Goldsmith’s (creaters and curators of the legendary Ubuweb) blockbuster anthology blew our minds with the possibilities of poetry – from Beckett to the Language Poets and beyond.

Happiness: Poetry After Rimbaud by Sean Bonney. Unkant.

Speaking of poetry, this collection served as a reminder of how poetry attempts to do the impossible.

The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated by Martin Hammond. Oxford University Press.

The translation is in crisp idiomatic English and the notes are genuinely useful to anyone lacking perfect recall of every event and character in fifth-century BCE Greece. If you thought that it was a straightforward battle between the forces of light, in the shape of democratic Athens, and darkness as manifested by totalitarian Sparta, think again.. Reading this book brings the uncanny sensation that every variation on the historical chessboard was played out some two and a half thousand years ago.

Summer of Hate by Chris Kraus. MIT.

A dark and bleakly humorous novel about flawed reciprocity and American justice, recording recent events through the prism of a beleaguered romance.

Revolution of Everyday Life by Raoul Vaneigem. Rebel Press.

Working on McKenzie Wark’s new book, The Spectacle of Disintegration we felt the thrill of Raoul Vaneigem’s Revolution of Everyday Life – one of those texts that you stumble on it and it feels like you’re receiving secret messages. We were hoping to co-publish the new updated translation by Donald Nicholson-Smith but it wasn’t to be – nonetheless we’re delighted that’s it out.

Communization and its Discontents, edited by Benjamin Noys. Minor Compositions.

This was released at the end of last year and is the first collection of pieces on the theory of communization, including Endnotes, Theorie Communiste, and Evan Calder Williams.

The Last of the Wine Mary Renault. Random House.

A historical novel recounting the Peloponnesian War from the perspective of two Athenian "friends." It's a wonderfully realized vision of a lost world and another instance of the draw the ancient world once had for gay writers (an appeal that I fear was often based on oversimplification).

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens. Penguin Classics.

Dickens is possibly the only great writer I know (perhaps Lawrence is an exception) who can take working-class characters seriously. Interestingly, they always have to remain working class. Only Dickens's villains are socially mobile. Don't listen to the haters. Should anyone ever turn their nose up at Dickens, you are morally obliged to put it out of joint.

Ulysses by James Joyce.

Ever since the copyright expired on Joyce's work, a much wider audience has been able to experience his work. This is a terrific, fully annotated edition.

Open City by Teju Cole. Faber & Faber.

One of the most powerful novels we have read in years. It tells of a young man drifting through New York, which sounds boring but is never less than gripping. It is a book haunted by a melancholy seen in the best kind of writer such as W. G. Sebald. We’re certain that it will be considered a classic of our times.

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin. Penguin.

Published in 1956, the intensity of this book has not diminished, and sadly, neither have the consequences of love and desire. An extraordinary tale of doomed love, sexual morality and human identity. Read it slowly, or you’ll regret finishing it so soon.

London's Overthrow by China Mieville. The Westbourne Press.

A stunning tour of a city drowning under the weight of an unrelenting financial crisis while the Olympic band played on.

Occupy Everything! edited by Alessio Lunghi and Seth Wheeler

A welcome collection of responses to Paul Mason’s theses on Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere

Bert: The Life and Times of A.L. Lloyd by Dave Arthur. Pluto Press.

This is a wonderful detailed biography of Britain’s own Alan Lomax. If you went to the launch party you were treated to an evening of the unsung heroes of Britain’s folk scene.

Maidenhead by Tamara Faith Berger. Coach House Books.

So often fiction that makes explicit attempts to annex theory goes horribly awry and reads like an undergrad discovering post-structuralism. Tamara Faith Berger's novel is a rare and wonderful exception. Experimental, raw, and a compelling page-turner, this story of a teenage girl's sexual and intellectual coming-of-age is a kind of contemporary écriture féminine that is as much Story of O as it is Giorgio Agamben, insightfully probing the nuances of power, race, and desire via a type of narrator--the adolescent girl--so often cast aside as frivolous.

And of course...

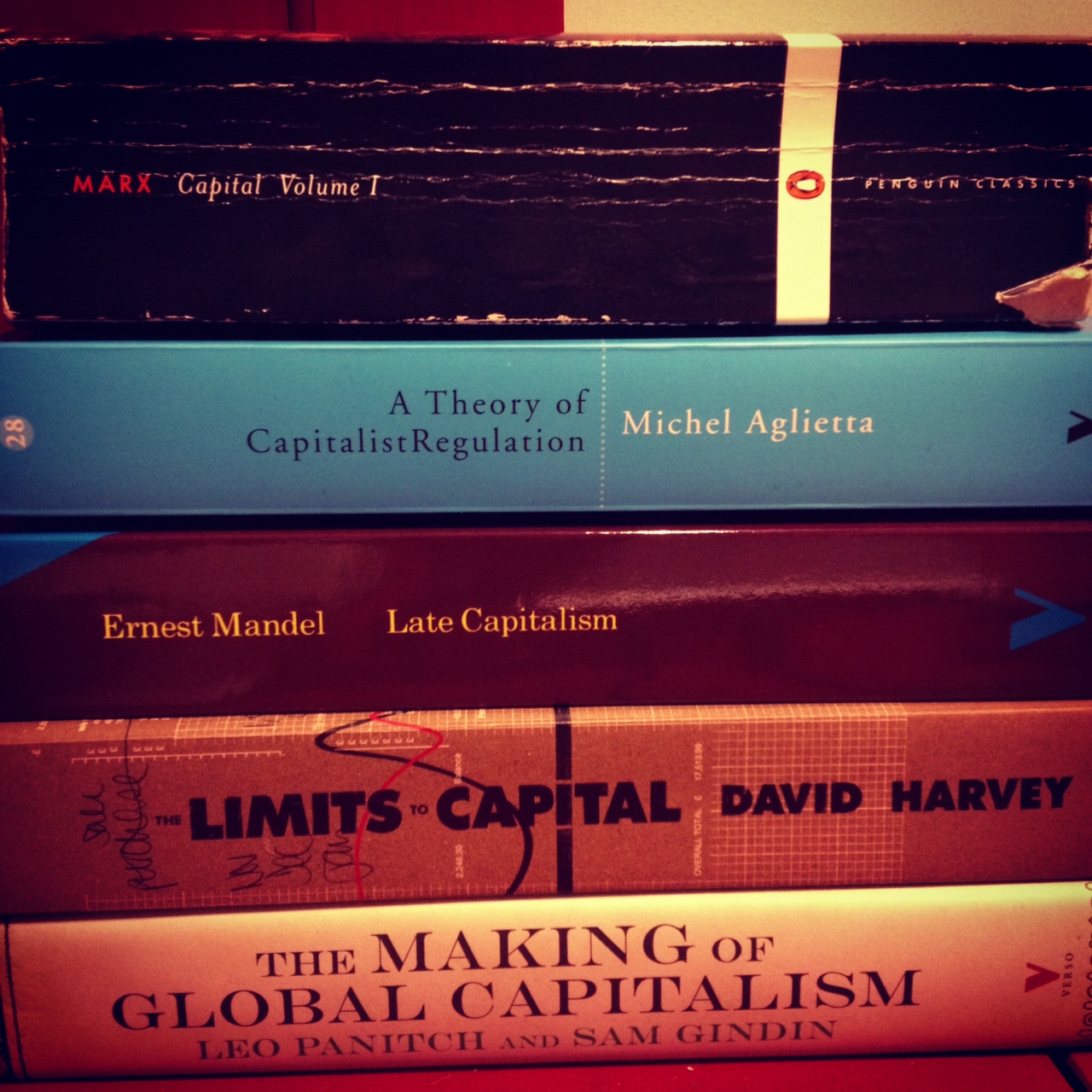

Capital, Vol. 1 by Karl Marx. Penguin Classics.

According to Matt, our Editorial Intern:

I started reading it again in the beginning in of the year and will finish it this week. If one reads 1000+ pages of Marx its hard not to become a bit Marxist. Before the proverbial 'end of history', I imagine many more people used to do this. Now that History (with or without a capital 'H') has been 'born again' and is potentially seeking its revenge (see Badiou, Milne, et al.), I've decided to read as much marxian/heterodox-economics and political-economy as I can – from Ernesto Mandel's Late Capitalism to Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin's The Making of Global Capitalism. And I'm not the only one. I used to think studying philosophy would tell me something about the world— it has in various ways, but as Marx said, the point is to change it.