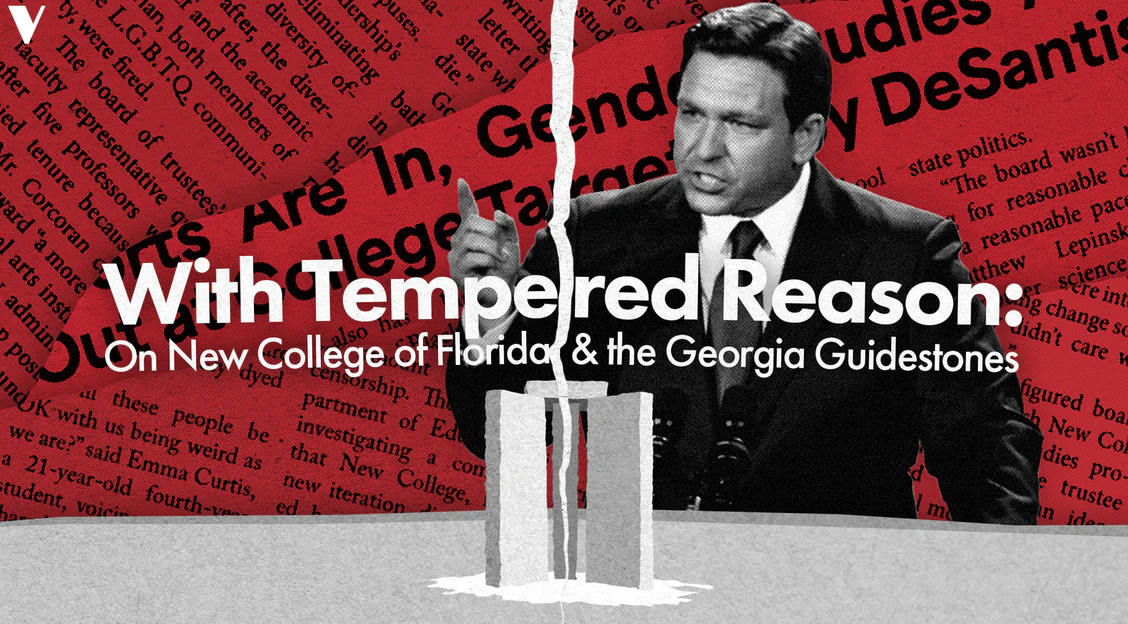

With Tempered Reason: On New College of Florida & the Georgia Guidestones

New College Alum V Conaty reflects on Ron DeSantis’s cultural takeover of the bastion of progressive education, and the importance of sites of free thinking in red states.

I.

It was 2012, a year around which rumors abounded about the end of the world. December 21st, the night that was supposed to be the last. The night was cold in the small town in northeast Georgia where Jessica and I were lost. We had been driving in circles on dirt roads between the empty fields at the edge of town—almost convinced that our destination, the Georgia Guidestones, had they ever existed, had disappeared—when suddenly headlights flashed on granite. I pulled up a sloped road into a gravel parking lot, and we stepped out into the damp air. The monument’s plinths jutted from the surrounding fields as if they had sprouted overnight from the ground they stood upon.

They seemed larger in person, in the dark, than in the pictures I had seen. I had expected there to be lights illuminating the monument, but there weren’t. We had passed the structure multiple times without realizing that the turn might be that inconspicuous. I grabbed my flashlight and turned it onto the stone nearest me. “Be not a cancer on the Earth - Leave room for nature - Leave room for nature,” the final guideline read where granite met gravel and a few patches of grass that grew in defiance of the cleared land below. A shiver ran through my body at that intersection, shaped by human hands, of stone and field and sky.

We spent probably twenty minutes there, silently circling, flashlights in hands, fascinated, lighting the granite slabs so we could read as much as we could of the inscriptions; the first principles tapered off into a darkness as complete as the silence. As she circled the stones, Jessica read the words out loud to herself, consulting her phone to read the topmost lines that our lights couldn’t reach. I don’t remember much conversation after we drove off that evening—just the weight of the granite sky that sparkled behind the stones, and the silence that settled inside us as we attended the structure.

The Georgia Guidestones were a monument that was erected at the bequest of an anonymous benefactor just outside the town of Elberton, Georgia in 1980. Branded by locals as “America’s Stonehenge,” the monument’s six slabs were carved from granite—the town’s main export around which the local economy was built. On the Stones were engraved ten guiding principles “[for] an Age of Reason,” as an explanatory tablet read, in eight modern and four classical languages. Apropos of their monolithic design, the structure was arranged as a sundial, marking the passage of the day and year by alignment with the sun. The identity of the wealthy benefactor, known only by the pseudonym R. C. Christian, and their intention behind the monument’s construction remain a local mystery and a topic of controversy, especially because the principles themselves and their design imply their intended use was as guidelines for a global society devastated by (and united by) calamity—utopian possibility in dystopian circumstances.

Our pursuit of the Stones had been tinged with irony. Jessica and I were in our second year of college, housemates, close in fits and starts; we had planned the trip only weeks beforehand, while we were both up all night finishing term papers. Neither of us believed the rumors, but we planned to visit the Stones at that final hour so that, when we got back to school the following month, we could tell our friends we had been there on the night the world ended. But by the time we left them, that irony had been replaced by a burgeoning understanding of the complex tensions between humanity and non-human life, justice and law, freedom and sacrifice. I left wondering if we would one day need to take the words to heart.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]

II.

In January 2023, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis appointed six members to New College of Florida’s Board of Trustees. The Sarasota Herald-Tribune reported that the justification for his government’s “conservative overhaul” of the school was political as well as financial, intended to transform New College into a conservative institution modeled on Hillsdale College—a private, conservative Christian college. Current students and alumni have quickly mobilized to raise awareness of this attack on the school’s culture of intellectual freedom. Only weeks later, DeSantis’s new conservative majority voted to terminate the contract of the school’s relatively new President Patricia Okker, a career educator, replacing her with former Republican House Speaker Richard Corcoron, a career politician.

New College was founded in 1960 as a private institution based on the values of free thinking, curiosity, and inclusion. The first class arrived on campus in 1964. While the school quickly acquired a reputation for academic freedom and excellence that attracted creative, independent students from across the state, it struggled financially. New College first became part of the state university system in 1975. In exchange for paying off the school’s debts, the college’s campus and assets were sold to the state. The state operated New College as an independent branch of the University of South Florida and funded the school at the same per-student rate. For twenty-five years the school continued to develop its unique curricular model and progressive campus culture, enjoying relative independence from the larger university. In 2001, during a broad restructuring of Florida’s state university system, New College of Florida was incorporated as the eleventh fully independent state school.

This is, more or less, the New College that I attended from 2011-2015: a small liberal arts college whose reputation had earned it national recognition and legislative designation as the state’s honors college, but whose state funding remained precariously dependent on per-student ratios that were designed for and favored the state’s large research universities. From the moment it became independent, New College was vulnerable to the Right’s attacks on higher education under the disingenuous guise of pragmatic austerity policies.

The political culture of Florida that has solidified in DeSantis’s tenure is increasingly characterized by right-wing populism, anti-intellectualism, and isolationism in a post-COVID environment wherein many of those who moved to the state during the pandemic did so to escape stricter public health restrictions elsewhere. And in 2023, another great migration may be about to begin in the opposite direction, as this administration’s policies drive an unprecedented number of queer and trans people to consider fleeing the state. In this environment, I question whether DeSantis’s decision to make an example of New College is truly about the school’s underperforming and not its reputation as a hotbed of progressive activism. Over the past several months it’s baffled me, and I’m sure many other Floridians, just how often national coverage of his administration’s policies seems willing to take the man at his word in good faith.

For years, New College’s students (and alumni) have been involved in organizing both locally and state-wide for progressive causes. As a Gender Studies major, this culture of activism provided real-world applications for the intellectual inquiries that many of my classmates chose to pursue. For example, one of my peers wrote her thesis on the correlation between access to safe, legal abortions and maternal health, and organized carpools to volunteer at Planned Parenthood on the weekends. Others organized trips to Tallahassee to protest statewide voter disenfranchisement. Leading up to the 2012 election, Sarasota was an obligatory campaign stop for GOP presidential candidates, and every campaign rally was met with a raucous counter-demonstration led by New College students.

Coverage of this takeover outside of Florida has latched onto New College’s small size as evidence of the school being an unfortunate but incidental casualty in a larger culture war rather than a strategic target for the Republican governor. Local news outlets have shown a greater awareness of the political expediency of making the school a battleground in the ongoing culture wars occurring in the state, especially around what the Right calls “woke” ideology. By making New College the testing ground for his vision for higher education, DeSantis can campaign on having “saved” the school from demise in the hands of his political opponents while neutralizing the threat that a hub of left-wing social activism poses to the success of his conservative agenda. His Communications Director Taryn Fenske attributed his administration’s current attempts to transform the school to its culture of “wokeness,” making clear the strategic intentionality of this choice, when she said “Unfortunately, like so many colleges and universities in America, this institution has been completely captured by a political ideology that puts trendy, truth-relative concepts above learning.” New College may be the first institution transformed by such an agenda but it will not be the last.

DeSantis’s attacks on New College should be understood as an extension of his administration’s other policies that vilify queer people and stoke Republican voters’ racial and sexual fears in order to drive voter turnout in Florida and increase his profile nationally in advance of his current presidential run—and I hate to say it, but it’s worked. In a state that has become increasingly hostile to queer and trans life and agency, where bills like the infamous “Don’t Say Gay” bill become law and where the governor has already signed a new bill which will prevent transition-related services from being covered by insurance, destroying safe spaces can also be understood as a strategy of managing domestic migration to and from the state along political lines. The expected faculty turnover has already begun at New College. By transforming an institution that has for sixty years been a bastion of progressive education, a hotbed of social activism, and a safe space for queer and trans students into a conservative Christian institution, the Right will force those students in Florida who need such a space to thrive to leave the state to do so, taking with them their votes and cementing the state’s newfound conservative majority.

[book-strip index="2" style="buy"]

III.

I’m not a journalist, but I am a writer. The conversation I want to have is less about New College itself and more about what New College represents within Florida: a beacon of intellectual freedom and community within a rapidly solidifying fascist state and an incubator of different ways of thinking and living in the world.

I have friends from many red states—many who have left, but some who have stayed—working against the far-right movements taking hold of their home states’ populaces. Their values diverge, at times, from each other’s and from mine, but on one point they all agree: they didn’t become leftists in the more liberal states some of them have moved to. They came into the beliefs and attitudes that guide their social and political lives through active participation in the communities that sheltered them in their conservative home states.

In On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint, poet and critic Maggie Nelson investigates the contentious value of freedom. In an attempt to reclaim the language of freedom from the “freedom to discriminate” espoused by the far-right, Nelson calls upon Michel Foucault’s “practices of freedom” as a model for understanding being free not as an end in itself but as an ongoing struggle, the tenuous outcome between conflicting drives toward personal liberation and communal care. The desire to be free can be either individual or collective. Individualistic freedom, in the world of American free market capitalism built on the backs of enslaved peoples, is necessarily a freedom from, and the choice to pursue that freedom is necessarily a choice to ignore that such a freedom has been purchased at the expense of other people. Collective freedom, on the other hand, reflexively acknowledges the inherent entanglement of people with each other and demands that practices of freedom include practices of care, which can look a lot like self-imposed constraints.

In Florida’s post-COVID political environment a web of bad-faith far-right freedoms including “parental rights,” “religious freedom,” and “anti-wokeness” has achieved rapid legislative success. That many of the bills that DeSantis has signed into law threaten, qualify, or effectively constrain the rights of many in the state—especially people of color; queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming people; and people of religious minorities—seems impossible to reconcile with the language of freedom that the Right uses to rally voters. But Nelson’s inquiry makes clear what these policies bely: that they ostensibly enshrine individual freedoms (for white, straight, Christian Floridians) which are perceived to be in crisis due to the increasing visibility and political agency of minoritized populations in America over the last several decades. But by restricting the rights of everybody else, what these policies actually enshrine is the exclusivity of these freedoms for the privileged classes.

But there have always been spaces in Florida, and more broadly throughout the South, where collective freedom is cultivated and practices of freedom taught that uplift the other alongside the self. Without these spaces, the brightest and most industrious potential leaders will likely leave the state, taking their skills and ideas with them. These spaces become ideological counterweights for those in power, teaching community members how to be active participants in democracy and work within the system to affect change; they check the authority of tyrannical leaders to enact laws that have the potential to harm the state’s constituents by providing alternative perspectives and networks for social organization. They also offer safe havens for those who would otherwise be isolated and ostracized, so that they too can live in and contribute to their local communities. Without safe spaces many marginalized people are left with little choice but to leave the state in order to find community.

[book-strip index="3" style="buy"]

IV.

Where I live in New York, many people don’t consider Florida part of the South. Everyone in New York has been to Florida, so it’s not the anonymous South of unambiguous bigots and chaste, destitute gays that they imagine when I say I’m from Alabama.

When I say I’m from Alabama, they sometimes ask “How was that?” or say, “What a shame they vote against their own interests!” Then I’m forced into the uncomfortable position of defending my home. But all of these reactions convey the same effect, a familiar liberal surprise I’ve learned to expect when having conversations about the South in New York City. It’s as if the person I’m speaking to has, for the first time, recognized the obviousness of what has never occurred to them before: that real people live in the states they've written off as flyover country, and their well-meaning, if under-informed, takes on our home states’ politics don’t help people there. There’s a familiar sense of cognitive dissonance that I’ve learned to recognize when a New Yorker realizes that my experiences in Alabama don’t confirm their own biases.

This conversation about whether Florida belongs to the South is interesting, because as DeSantis’s policies have begun making the state more dangerous for queer and trans people, I’ve been hearing more variations on the sentiment “I never thought this could happen in Florida.” I take this to mean that people outside the state have begun to realize what locals already know: that Florida, however culturally unique within the Southeast, is not the liberal bubble many expect it to be. I sometimes wish the same logic would be applied in reverse, to the rest of the South, so that people outside it would understand that neither the region nor the states themselves are monoliths.

Based on how I talk about Birmingham now, one might not guess how much I struggled for years with Alabama’s conservatism. I attended middle school at a time and place before general acceptance of gay kids by their peers could be assumed. I understood from a young age that I wouldn’t have a future in Alabama. Now I take care to avoid reifying stereotypes that paint the South in broad strokes as a backwater of bigotry and hatred—stereotypes which undermine the political agency of those who stayed, either by choice or for lack of mobility.

The stories I tell about my life have changed as my relationship to Birmingham has changed. Rather than mentioning how I learned what faggot meant in third grade or that my first boyfriend’s parents transferred him to a Catholic school after an administrator saw us kiss at a school dance, I talk about my family and community. Volunteering at Birmingham AIDS Outreach with my brother, driving peers around the state to interview queer teens about their experiences in school. Attending my first Pride parade at sixteen, where I watched my dad march with his partner. Attending their wedding—the first gay wedding to be officiated within their church—everybody in the audience crying tears of joy and relief.

But when I was young I had to find ways to live in Birmingham. First, I left my zoned district and applied to an arts high school downtown. I started participating in the local gay community around the same time. When it came time for me to apply to colleges I didn’t consider in-state schools. I understand the privilege I had, to be able to make these choices, and that if others hadn’t stayed in Alabama and created the safe spaces that I took for granted, they wouldn’t have existed. But at the time they felt like the only choices I could make.

New College was my way out, and I began building a life there in earnest. I dove into the confusing emotional terrain of gender and sexuality and made them the focal points of my academic studies. I started using gender-neutral pronouns, changed my name. Then, at the same time, my relationship with Alabama and the South started to mature. The distance, in this case, from the valley where I spent my adolescence looking outward made it easier to look inward and understand the ways that my upbringing in the South—not only by my family, but also within the communities I was a part of—had already made me who I would become.

It’s difficult for me to narrativize the events that led to this change in perspective. It’s not as simple as saying that New College taught me to look for social context. I can only say that this change had already begun when I arrived in Sarasota and was still underway when I left Florida four years later. Talking to fellow students with complicated relationships to their own hometowns, many of them from Florida but some from farther afield, helped advance this process. So did my Sociology courses, which helped me to better understand structures of power that disenfranchise voters in the South and prevent change from happening through electoral politics and showed me the importance of grassroots activism. In the end it makes the most sense to me to think of this as a kind of relationship that grows in fits and starts.

The trip I took with Jessica was one of many turning points in my relationship to my home region. Through my windshield I saw the South with a continuity that I had never experienced before, and my life within it in a new light. Standing in front of the Guidestones, I was amazed that, in the middle of that field in northeast Georgia, was a monument whose messages advocated for a secular humanist society in harmony with nature in a state where such seemed impossible. I realized then that such sites exist everywhere, and their value stems from the new ways of being and imagining that they make possible.

As Florida has swung faster and harder to the right, my desire to escape Alabama for safer shores seems naive. I’ve begun to appreciate the relative safety and access I had in Alabama that doesn’t accord with common narratives about being queer in the South. But as my homestates have become increasingly hostile to queer and trans lives, the need I felt to escape has slowly been reaffirmed by history. The truth is that my adolescent years might have been the safest time to be a queer child in Alabama, then a trans young adult in Florida, and those spaces where I found possibility in both states are currently under attack.

[book-strip index="4" style="buy"]

V.

That the natural state of the human spirit is ecstatic wonder.

That we should not settle for less.

Motto of the New College Student Association

Rule passion – faith – tradition – and all things with tempered reason.

The Georgia Guidestones

If one were to take a detour to the Georgia Guidestones today, they would find a dirt road sloping into a gravel parking lot in an empty field. The ideas enshrined in stone are no longer there.

An explosion rattled Elberton in the early morning hours of July 6, 2022. Ten years since Jessica and I had consulted the stones on the night the world ended, they had become a lightning rod for far-right conspiracy theories after Kandiss Taylor, a failed far-right gubernatorial candidate called for the “Satanic” stones to be destroyed earlier that year. There had been such calls before, but Elberton locals suggest that the attention their tiny town had been getting in the previous several years had escalated with these conspiracy theories. Where visitors to the Stones used to come from all over the world to see “America’s Stonehenge” and spend money in the town’s small economy, since 2019 curious tourists have been outnumbered by vandals and Q-Anon believers promoting the Stones’ destruction. When they got their wish, Taylor claimed that the monoliths were struck down by a bolt of lightning, an act of God. Evidence points to their destruction, like their creation, being by human hands, but there remain no suspects. Now, almost a year later, Elberton locals feel the loss of this monument and the small but significant tourist economy that was built on its existence.

Less than a year after reading about the destruction of a monument in a small town in Georgia, I found myself reading article after article about the hostile takeover of my alma mater. These small sites’ outsized profiles were distorted by the far-right to justify their destruction. Communities had been built around them and will suffer in their absence. New College of Florida—itself a monument to humanist values and an artifact of a past time when Florida was a haven for deviant ideas, when an experimental college could thrive there—might soon be the next casualty in a war of ideas that threatens collective freedoms across the country. This war has greater implications than the loss of two personally significant sites; though its initial battles may have begun in Red states, its consequences will extend beyond the South.

In writing this post I’ve had to simplify my relationship to New College in order to advocate for its value. I’ve avoided talking about violences I witnessed or endured, even though these experiences are integral to the ways that New College’s student community has shaped me as a person. To go into detail would be to unravel a more complicated relationship than I can examine in this post. It would mean diving into conversations about substance abuse, sexual assault, campus policing, and how the law fails to protect individuals from violence because its primary function is to protect institutions from culpability. I haven’t broached these conversations because these violences are not unique to New College—rather, they are endemic to every institution of higher education in the country—and because doing so will detract from my point that a space like New College matters in a state like Florida.

My relationship to the Guidestones is also more complicated than I’ve been able to address. Some of their proposed responses to the impossible problems of a not-so-hypothetical future have rightly been critiqued as verging on eugenicist and engaging in the rhetoric of eco-facism. My goal isn’t to defend these principles, but instead to suggest that any attempts—however flawed—to reckon with the entanglement of human and non-human life, individual and collective freedom, and national and global concerns should be considered under threat of a more corporeal present fascism.

What I’m trying to say is that New College doesn’t need to be perfect nor does it need to provide actionable visions of a utopian future in order to be worth preserving.

Looking backward and forward at the long road to perspective, I come back to the above quotes. The tensions between these two principles that have shaped my adult life—ecstatic wonder and tempered reason—mirror the complexities of Nelson’s understanding of living in the tensions between drives toward freedom and care. If ever there was a time to listen to these guidelines which were carved in stone—metaphorically, in the case of New College, and literally, in the case of the Guidestones—it would be now. I can only hope that those of us who came of age in the times and places when they were will carry them with us into the future where they are still needed.

[book-strip index="5" style="buy"]VI.

When my editor and I first discussed this piece, we initially wanted to publish on a shorter timeline in response to DeSantis’s takeover of New College’s Board of Trustees and the firing of Patricia Okker. However, we soon realized that New College will remain in the public eye as a battlefield in an ongoing fight for academic freedom.

Several bills—including Senate Bill 266 and House Bill 999—have been passed that aim to apply DeSantis’ vision for higher education across the state university system. As the New College BOT implements apparently innocuous changes, such as forming a new athletics department and courting fraternities and sororities—cultural programs that call to mind the Nazi strategy of promoting fascist policies through recreation and leisure programs such as Kraft durch Freude (Strength Through Joy)—the state has moved to scrub higher education of programs and offices associated with “woke” ideology statewide. Gender Studies and African American Studies programs have been the first to be demolished, alongside affiliated offices of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. But with the passage of these bills, any reference to axes of power along the lines of race, gender, or sexuality in higher-level social science and humanities classes will be subject to external review.

On May 15, DeSantis held a press conference at New College—in a building where several previously scheduled finals had to then be rescheduled on short notice—where he publicly signed HB99/SB266 into law. During finals week, and despite his publicity stunt being announced only hours beforehand, students and alumni gathered outside the building in protest. Days later the graduating class of 2023 continued to protest at their own commencement ceremony, turning their backs and chanting during the speech by board-selected commencement speaker Scott Atlas, an advisor of Donald Trump during the COVID-19 pandemic who was openly critical of the Center for Disease Control’s public health advisories.

On May 17, DeSantis signed several anti-trans bills into law, including a gender-affirming care ban, a bathroom ban, and bills to restrict drag performance across the state. To stay up to date on anti-trans legislation in Florida and similar bills across the country, follow activist Erin Reed on social media or subscribe to her Substack.

***

V Conaty is a writer, editor, and producer based in Brooklyn and Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley. They are a recurring guest-host at Commonplace: Conversations With Poets, a literary conversation podcast founded by the poet Rachel Zucker. One of New College of Florida's Class of 2015, they hold a degree in Gender Studies.