Why We Need Benjamin Lay

Benjamin Lay was a class-conscious, race-conscious, gender-conscious, environmentally conscious man with a fully integrated radical worldview; he was “intersectional” almost three centuries ago!

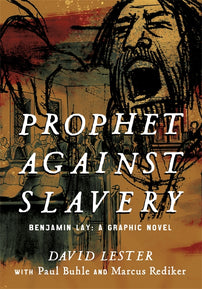

Prophet Against Slavery: Benjamin Lay, A Graphic Novel brings to life an unusual historical figure, the radical eighteenth-century Quaker Benjamin Lay, one of the first people to demand the worldwide abolition of slavery.

Benjamin happened to have dwarfism; he stood around four feet tall. He enacted guerrilla theater against rich Quaker slaveowners, spattering them with fake blood to humiliate them in public. He drew their wrath and was punished for his direct action. Four different Quaker meetings, two in England, two in the United States, excommunicated him; he was the most disowned Quaker of his era.

Even though Benjamin was well known in his own day—despised by many, loved by some—he disappeared from public memory in the late nineteenth century and has only recently begun to return. David Lester, Paul Buhle, and Marcus Rediker created this graphic novel to recover his inspiring life for our tumultuous times.

Benjamin was a revolutionary. He wanted to “turn the world upside down”—a Biblical phrase often used during the English Revolution to signal the overthrow of the rule of monarchy, gentlemen, slaveowners, patriarchs, and all other kinds of oppressors. This ordinary worker wrote a blistering attack on rich men who “poison the earth for gain.” He insisted that slave masters were literally the spawn of Satan and must be crushed, their victims emancipated. He believed that men and women were equal, and indeed he subverted the Quaker gender hierarchy by sitting in the women’s section during worship services.

He agreed with Pythagoras that people who kill animals will always kill each other. He was committed to animal rights and was therefore a vegetarian, more specifically a vegan, two hundred years before the word was invented. He abjured luxury as corruption and lived in a cave (with a big library). He grew his own food and made his own clothes to avoid exploiting the labor of others. He refused to consume any commodity that oppressed people were forced to produce. He rejected the tea manufactured on plantations in India and likewise the sugar made with the blood of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean. Benjamin was a class-conscious, race-conscious, gender-conscious, environmentally conscious man with a fully integrated radical worldview; he was “intersectional” almost three centuries ago!

What can we learn from the life of Benjamin Lay? We can learn about the traps and perils of complicity, the ways large and small by which people often unwittingly participate in and perpetuate systems of injustice. By pioneering the boycott of slave-produced commodities, Benjamin created the principle that animates current global struggles against sweatshops operated by Nike and other multinational corporations. Benjamin also made clear that we must not let the markets of capitalism govern our lives, because all commodities disguise their origins in human labor and implicate us in oppressing others. He recognized before almost anyone else that every consumption choice was political and ethical, from smoking Virginia tobacco to eating beef.

Benjamin Lay also teaches us about the power of solidarity and agitation. He considered all of the natural world, human beings as well as animals, to be his “fellow creatures,” a phrase often used among those who sought to turn the world upside down in England in the 1640s and 1650s. Much of what Benjamin knew about solidarity he learned during the twelve years he worked at sea as a common sailor.

Seamen entrusted each other with their lives every day at sea and developed strong bonds among themselves amid the danger; they created fictive kinship and called each other “Brother Tars.” Benjamin took solidarity further by offering compassion and practical assistance to all who worked under hard conditions, especially the enslaved Africans he met in Barbados and Pennsylvania. But Benjamin made it clear that solidarity was not enough to achieve justice. One also had to “speak truth to power.”

This self-educated philosopher had read the radical thinker of ancient Greece, Diogenes, who was committed to parrhesia, radical free speech. Benjamin spoke fearlessly to the rich and the mighty throughout his life. He advanced his causes through direct confrontation and productive controversy. For or against, all those who knew Benjamin discussed his ideas.

Like an Old Testament prophet, Benjamin warned Americans that if they did not follow his demand to abolish bondage immediately, the legacy of slavery and racism would be profound and lasting. He wrote in 1738, in his scorching book All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, slavery “will be as the Poison of Dragons, and the cruel Venom of Asps, in the end, or I am mistaken.” Almost three centuries later, we are still trying to get the poison and the venom—structural racism and its many injustices—out of the body politic.

Benjamin imagined a world without slavery at a time when most people of European descent considered the so-called peculiar institution to be as natural and as eternal as the sun, the stars, and the moon in the heavens. Since Benjamin fashioned his critique of slavery two full generations before antislavery movements developed in the 1780s, it took time for people to catch up to his progressive ideals. His fellow Quakers, who had repeatedly disowned him, finally, in 1776, became the first group to abolish slavery in their own midst: it was no longer possible to be a Quaker and own a slave.

Energized by Lay’s radicalism, Quaker abolitionists influenced Thomas Clarkson and the early abolitionist movement in England, as well as the Société des Amis des Noirs in France. Benjamin was a transatlantic vector of revolution, a line of force. He should be remembered as a major contributor to the struggle against slavery.

And yet he was, for many years, almost entirely forgotten: Benjamin came from the wrong class; he had the wrong kind of body; he used the wrong methods of protest; he espoused ideas considered too radical. With this graphic novel, David Lester has helped bring him back for a new generation of readers, who might just see in Benjamin’s story creative possibilities for a better future, in which we can all live together on “the innocent fruits of the earth” in genuine, abiding peace and equality.

— an edited excerpt from Prophet against Slavery: Benjamin Lay, A Graphic Novel

Illustrated by David Lester, Edited by Paul Buhle and Marcus Rediker