In his time, Benjamin Lay may have been the most radical person on the planet

Benjamin Lay was one of the first practical abolitionists, grounded in the real day-to-day struggles of enslaved peoples of African descent.

Benjamin Lay was, in sum, a class-conscious, gender-conscious, race-conscious, environmentally-conscious vegetarian ultraradical. Most would think this combination of beliefs possible only since the 1960s, two full centuries after Lay’s remarkable life ended. He lived the principles that today animate a global movement against sweatshops, whose logo-adorned clothing and shoes disguise the horrific conditions under which workers produce them. As the first person to boycott slave produced commodities, Benjamin pioneered the politics of consumption and initiated a tactic that would become central to the ultimate success of abolition in the nineteenth century. In his time, Benjamin may have been the most radical person on the planet. He helps us to understand what was thinkable and what was politically and morally possible in the first half of the eighteenth century—and what may be possible now. It was more than we thought.

Benjamin Lay’s dwarf body shaped his radicalism. For someone “not much above four feet” tall, life was a struggle to be considered equal, even to be taken seriously in many situations. Benjamin had to fight. He had to insist on the Quaker community’s commitment to equality, an ideal he saw as besieged on all sides by covetousness and corrupting wealth. He had to speak freely, achieve self-sufficiency, and cultivate toughness. He waged a politics of the body every day of his life—with compassion and empathy. He was profoundly moved by his experience of slavery in Barbados and again in Pennsylvania. He expressed concern for the poor throughout his life. Benjamin was thrice an outsider to mainstream society, as a religious radical, an abolitionist, and a dwarf. His experience as a little person, coupled with his commitment of universal love to all peoples, turned compassion into active solidarity. Benjamin’s life as a dwarf was thus another key to his radicalism—a deep source of his empathy with enslaved and other poor people, with animals, and with all of the natural world.

Through him flowed the resistance of the early Quakers, deep-sea sailors, ancient philosophers, hardy commoners, and enslaved Africans. Through him lived on democratic and egalitarian principles into the modern age. Benjamin was, in many ways, the last radical of the English Revolution. Benjamin would reinvent and expand the legacy, not least by attaching the uncompromising spirit of antinomianism to the antislavery cause, effectively linking the English Revolution to a broader struggle over slavery and freedom. The radical ideas and practices of the English Revolution would migrate across the Atlantic, then return to Europe to help ignite the “age of revolution” in the late eighteenth century. Benjamin was a vector of connection and causation in this process.

Benjamin was also one of the first practical abolitionists, grounded in the real day-to-day struggles of enslaved peoples of African descent. His radicalism was driven by close personal proximity to slavery and its attendant horrors, as the French revolutionary Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville observed in 1792. Noting that abolitionists were frequently criticized for “having not been witnesses of the sufferings which they describe” in their writings about slavery, he was quick to add, “This reproach cannot be made against Benjamin Lay.” Benjamin’s experience in Barbados, where he saw the “horror inspired by the frightful terrors of slavery” and where he developed personal relationships with enslaved people, caused him “to preach and write for the abolition of slavery.” He engaged in “profound meditations,” showed “an indefatigable zeal for humanity,” and created “a life without a stain”.

Sources are lacking to explore Benjamin’s personal involvement in the lives of enslaved people in and around Philadelphia. We do not know, for example, whether he helped bondmen and bondwomen to escape to freedom through what would have been a forerunner of the Underground Railroad, which developed a century later with the growth of a national abolitionist network. Such action would have been consistent with everything Benjamin believed and preached. We do know, however, that he advocated incessantly for emancipation, in some cases on behalf of specific individuals he knew.

One such person was a “negro girl”—her name has not survived in the evidence—who was owned by Quaker neighbors in Abington. Benjamin argued repeatedly with the man and woman about the iniquity of keeping slaves, insisting that the girl be freed, but to no avail. The couple not only kept her in bondage; they justified the practice. One day Benjamin explained to them the “wickedness” of the slave trade, emphasizing how it separated children from their parents. Soon after, Benjamin encountered the six-year-old son of the couple a short distance from their farm. He invited him to his cave about a mile away and entertained the boy all day inside, out of view.

When evening came on, Benjamin observed the boy’s father and mother running toward his dwelling. He advanced and met them, “enquiring in a feeling manner, ‘what is the matter?’” The parents replied in anguish, ‘Oh Benjamin, Benjamin! our child is gone, he has been missing all day.’” Benjamin listened with sympathy, paused, and said, “Your child is safe in my house.” Then he explained why he was there: “You may now conceive of the sorrow you inflict upon the parents of the negroe girl you hold in slavery, for she was torn from them by avarice.” Once again Benjamin expressed a simple, profound message: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. In this case the other was a particular human unjustly held in bondage.

Benjamin’s prophecy speaks to our time. He predicted that for Quakers and for America, slave keeping would be a long, destructive burden. It “will be as the poison of Dragons, and the cruel Venom of Asps, in the end, or I am mistaken.” As it happens, the poison and the venom have had long lives indeed, down to the present, as we still live with the consequences of slavery: prejudice, poverty, deep structural inequality, and premature death. Just as tellingly, Benjamin counseled his readers to beware rich men who “poison the World for Gain.”

Despite his prophecy, Earth has grown much sicker since Benjamin’s day, which makes it easier now to hear his message. It may have taken more than two and a half centuries, but it seems that the world is finally beginning to catch up with the prophet’s radical, far-reaching ideas through a growing, if far from universal, environmental consciousness.

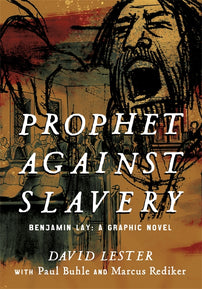

[book-strip index="1"]