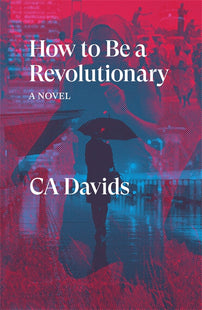

How to Be a Revolutionary: A Letter from the Editor

Author C. A. Davids was born and lives in Cape Town, but has lived in New York and Shanghai, and in this formally complex and transnational novel, she sets these worlds into orbit around each other, but doesn’t try to make them neatly align.

Andrew Hsiao is the editor of How to Be a Revolutionary, a novel by C. A. Davids, which is on sale February 8 and a selection in our Book Club. See all of our winter book club selections.

For months my comrade Anjali Singh, editor and agent, had been telling me about a manuscript that she said I might just love and that was almost ready, just as I had been telling her for even longer that Verso’s fiction imprint was almost ready.

Then one day these things were ready to hand, and I found myself following the progress of a Cape Town woman named Beth, ambivalently employed in the South African diplomatic service in China, as she gingerly tries to negotiate a new posting, and a new world, in Shanghai. Maybe because she’s in that peculiar state of openness you might find yourself in when you’re thinking of leaving someone (her husband back in Cape Town), she pursues an unlikely friendship with an enigmatic older Chinese man, Zhao. Beth and Zhao walk the streets of Shanghai and bond over a shared love of Langston Hughes.

And then Zhao disappears, leaving her with a manuscript. This text, parts of which are reproduced in How To Be a Revolutionary, tells the grief-stricken, intensely moving story of Zhao’s mother’s collision with history–her perishing, along with millions of others, in the Great Famine caused by the Great Leap Forward. The heartbreak is only heightened by Zhao’s regretful admission that he–a revolutionary journalist–kept this bitter story under wraps his whole life, since it was politically inconvenient. He asks her to find a way to get it published.

As Beth deliberates, her own grave doubts about the revolutionary bonafides of the post-apartheid ANC–and her complicity in its corruption–make her sad about her own descent into complacency. As a teenage anti-apartheid activist, her incandescent, fearless friend Kay provided a model of how to be. But then what happened to Kay, well…in any case, Beth is no longer a teen but someone with a tenuous marriage and an uncertain career.

Into this moral dilemma, C.A. Davids drops a series of letters Hughes wrote to a South African comrade, in which the Harlem intellectual wrestles with how to be an internationalist and a revolutionary—and how to be less lonely—all while under threat from anti-communist inquisitors (Hughes was hauled before Joe McCarthy’s Senate Subcommittee in 1953). Hughes’s inimitable tone of jaunty anger reminds us that, like Martin Luther King Jr., he is often sanitized when remembered today, whereas the real-life figure was deeply radical (but also melancholy and struggling with how to be). Perhaps Hughes is a model for Beth.

Of course, Zhao’s haunting, raw memoir; Beth’s rueful reflections; and in this book, even Hughes’s funny, caustic letters are all entirely inventions of Davids. She was born and lives in Cape Town, but has lived in New York and Shanghai, and in this formally complex and transnational novel, she sets these worlds into orbit around each other, but doesn’t try to make them neatly align. Possibly this intricate interplay suggests that politics is not solely about ourselves nor only about others–it has more to do with connections and solidarity–just as people are not simply privileged or oppressed, but both. It’s a beautiful book, and absorbing, and I have a feeling that you might just love it.

–Andrew Hsiao,

Verso editor, Brooklyn, January 2022