Halifax as a Chartist Centre

Previously unpublished essay on the town of Halifax as a centre of Chartist activity by historians Dorothy Thompson and E.P. Thompson.

Note: This is the original version of 'Halifax as a Chartist Centre'. Typos and omissions in the notes have not been corrected. An edited version appears in The Dignity of Chartism: Essays by Dorothy Thompson (London, 2015)

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]I

‘Our borough of Halifax is now brightening into the polish of a large, smoke-canopied commercial town’, Miss Lister, owner of Shibdon Hall, noted ironically in her diary in March 1837 (1). Head of an old and influential family, owning land, mines and property in the town and environs, her resentment against the March of Progress reminds us that Halifax was no mushroom-growth of the early nineteenth century. The upper Calder Valley, once the classic site of the domestic industry recorded by Defoe, was a stronghold of the small clothier well into the century. In Halifax there had been built the last of the West Riding ‘Piece Halls’, at which the stuff manufacturers still attended in Chartist times. The plentiful supply of water in the parish had delayed the introduction of steam, while scores of small masters established little water-powered spinning mills in the outlying cloughs and deans. Drouth in the 1820s speeded the introduction of steam; larger mills were built in the main valley bottom alongside the Rochdale canal; the advancing worsted industry became concentrated in fewer hands. From the large enterprises of such people as the Akroyd family there came much of the smoke and the ‘polish’.

The parish of Halifax in 1831 was the largest in England, stretching from Brighouse in the East to the Lancashire border at Todmorden seventeen miles to the West, and taking in a large upland population alongside the Calder and its tributary, the Ryburn. The population of the parish was close on 110,000, although the rapidly-growing township made up only 15,000 of this figure (2). ‘A great proportion of its population’, said a witness in 1829, ‘is not like that of Leeds, employed in the warp and woollens, nor in stuffs, as at Bradford, or fancy goods, as at Huddersfield or cottons, as at Manchester, but its trade is a mixture of all these combined …’ (3).

The parish contained by far the largest concentration of the cotton industry in Yorkshire (4); while Halifax was second only to Bradford as a centre of the rapidly expanding worsted industry. A return of mills in the parish in 1831 shows 57 cotton, 35 woollen, 45 worsted and 4 silk: employing in all above 18,000 juvenile and adult workers. A further return, in 1838, shows 80 worsted and 63 woollen mills; 71 cotton and 7 silk (5). While many of these were small and insecure ventures, large- scale enterprises were emerging, notably that of Jonathan Akroyd and his son Edward (employing, in 1845, 6,400 workers inside and outside his mills (6)) and that of the Crossley brothers, whose first large carpet mill at Dean Clough was built in 1841. By the boom year of 1850 over 15,000 workers were employed within the walls of the parish worsted mills alone (7).

Underneath the gathering canopy of smoke, there was to be found the same ‘polish’ as in other West Riding towns. Juveniles comprised nearly one third of the labour force within the mills of the parish in 1835; one half of the force of the borough in 1850 (8). The Halifax masters were among the most intransigent and uninhibited opponents of factory legislation (9). Wages, even in the new power-loom sheds, were low:

‘One man told me, with tears in his eyes, that he had been four weeks (six days in a week, and twelve hours a day) in earning 19s 6d at weaving with the power-loom. Formerly he could earn upwards of 20s a week by hand’ (10).

While some restraining influences were to be found in the township and immediate environs, the outlying districts and remoter valleys exhibited the blackest vices of early industrialisation. Page after page of Michael Armstrong might well have been drawn from such an isolated part as Cragg Dale, whose mill owners (one clergyman exclaimed) 'are the pest and disgrace of society … They say, “Let the Government make what laws they think fit; they can drive a coach and six through them in that valley’ (11). Here the abuses of truck were carried to extremes. ‘What say the shopkeepers of Rochdale about you?’, demanded Oastler:

‘Why, when they have stuff that they can’t sell to anybody else, they say to their apprentices, “Lay it aside for the Craggdale manufacturers to sell to their work people.” Why, you stink over Blackstone Edge!’ (12).

While the Mytholm and Colden silk mills were 'centres of democratic opinion', where the New Moral World circulated and Socialist Utopias eagerly debated (13), the strength of Chartism in the parish was to be

drawn not in the first place from the mills but from the thousands of handworkers - weavers, combers and others - who entered their long agony at the beginning of the decade. In 1832 Cobbett found the weavers of the valley to be ‘extremely destitute’: where they had formerly earned 20/- to 30/- a week, they were now reduced to 5/-, 4/- or less. ‘It is the more sorrowful to behold these men in this state, as they still retain the frank and bold character formed in the days of their independence’ (14). As the decade dragged on, continued parliamentary attention (15) served only to keep alight among the weavers a glimmer of hope in legislative assistance, and to bring redoubled bitterness when their desperate plight in the 1840s was met with nothing more than expressions of regret. The majority of them were now living on the edge of starvation, subsisting upon oatmeal, oatcakes, skim milk and potatoes. Despite the healthy moorland surroundings, their cottages were often insanitary, decaying and bare of furnishings, while the upland hamlets, (from the debility of the population), were as subject to epidemics as the slums of the town. ‘How they contrive to exist at all’, exclaimed a surgeon who has visited the weavers’ cottages at times of childbirth and sickness, ‘confounds the very faculties of eyes and ears’ (16).

The yeoman clothier of Defoe’s time had either – like the founder of the Akroyd fortunes – prospered as a manufacturer, or been reduced to the status of a hand-loom weaver (17). The increased output of yarn from the spinning mills had led to a brief period of prosperity for the weavers, and an influx of labour into the trade. While in Halifax some manufacturers – notably in the carpet industry – employed handloom weavers on their own premises, the great majority of weavers outside the township worked in their own homes, sometimes owning their looms, sometimes paying rent for loom and tackle, and living in perpetual indebtedness to their employers (18). Manufacturers, master spinners, or intermediate factors, put out the yarn among the weavers, paying them for the labour of the various weaving processes when the piece was finished.

The weaver was not an independent craftsman but a wage-labourer, working (like most outworkers) in exceptionally vulnerable conditions. His whole family employed – his children winding bobbins, his wife sometimes at a second loom – he had no regularity of employment, had to meet his own overheads (rent, candles, sizing etc), was subject to fines for spoilt work, and received no payment for time spent in fetching and carrying his work, setting up his loom, and a dozen other processes (19). His wages were beaten down by successive competing employers, the least scrupulous or least successful setting the pace. The employer was liable to no overheads, and need fear no costs of idle plant during bad

trade; he need only put out more or less yarn according to the state of the market (20). The degradation of the weavers was not caused by, but antedated, the widespread introduction of the power-loom; and, indeed, so far from the power-loom being the first cause of the weavers’ suffering, the slowness of the introduction of the power into worsted and (even slower) into the woollen industry, may be attributed in part to the cheapness of labour by hand. Correspondingly, the exploitation of the hand workers contributed to the debasing of wages in the power-loom sheds (21). As the mills continued to draw upon women and juveniles for a high proportion of their labour force, the adult men – without prospect of employment – preferred to find occasional work in the relatively unskilled trades of weaver or comber to the alternatives of total unemployment. Hence these two trades represent in the Chartist period an enormous pool of disguised unemployment in the parish.

The entry of the power-loom weavers served to bring the long agony to a crisis in the 1840s. Coming first into cotton (and affecting especially the coarse fustian trade carried on extensively in the upper Calder Valley), it threw more hand-looms onto the support of the worsted and woollen industries. In 1827 James Akroyd built the first large worsted power- loom shed in Halifax and introduced the Jacquard loom: ten years later the firm opened its Haley Hill mill, the largest in the worsted industry of the time : by 1850 there were 4000 power looms in the worsted industry in the parish (22). Meanwhile the power loom was being rapidly improved in efficiency (23). But the hand weaver was not presented with a head-on contest with the machine as the hand comber was to be in the early 1850s. Rather, there was a complex series of repercussions within an industry whose total output was increasing by leaps and bounds over the whole period (24). Forced out of cotton, facing severe competition with power in the worsted industry, the hand-loom was still the mainstay of the fancy woollen and carpet industries (25). Indirectly power competition served to intensify the exploitation of the weavers in these industries as well by flooding the remaining markets with labour. But this delayed and uneven development helps to explain the extreme tenacity of the weaver’s generation-long struggle with starvation, which co-incides with the rise and decline of the Chartist movement.

The worsted weavers of the district bitterly resented the introduction of power, demanding legislative restrictions upon its use, and (in 1835) protesting against:

' … the unrestricted use (or rather abuse) of improved and continually improving machinery …

… the neglect of providing for the employment and maintenance of the Irish poor, who are compelled to crowd the English labour market – for a piece of bread.

… The adaption of machines, in every improvement, to children and youth and women, to the exclusion of those who ought to labour – THE MEN' (26)

If trade union combination had been next to impossible before, in a scattered cottage industry riddled with variations of prices and practices, it was now out of the question. But – even if the weavers had not had strong traditional and moral objections to factory discipline and the factory system – age, inadaptability and lack of alternative employment prevented their absorption into other occupations (27). Their spokesman Benjamin Rushton - who was to become the most notable of Halifax Chartist leaders – declared their condition in 1835 to be:

‘so ruinous that, if matters are suffered to go on as they have done, and are doing … that useful body will very soon be annihilated, or they must degenerate into paupers, poachers or thieves’ (28)

Under Rushton’s leadership, they became Chartists instead.

The plight of the hand woolcombers was little different. Wage labourers, some working in small workshops, some in their own houses, they had pioneered trade unionism in the worsted industry. While Bradford was the centre of trade unionism, Halifax took second place, and many Halifax combers (as well as worsted workers) had taken part in the long strike of 1825 (29). From this year forward their decline set in apace, although serious competition from combing machines did not come before the 1840s. Working and living in cramped quarters, amidst charcoal fumes from the comb pot, their poor health and short span of life was a subject for frequent comment:

'Another peculiarity about these woolcombers was that were almost without exception rabid politicians … The Chartist movement had no more enthusiastic adherents than these men; the Northern Star was their one book of study …’ (30).

The swift introduction of improved combing machines after 1845 brought matters to a sudden crisis (31), although in Halifax the final extinction of the hand combers was delayed until 1856 when Edward Akroyd, who employed between 1000 and 1500 combers, replaced their labour with machines (32).

While the textile industries pre-dominated, still more than one half of the adult working population were engaged in a diversity of occupations.

Within a mile or two of the town’s centre were a dozen small mines, where young women and children on all fours dragged loads down passages 16 to 20 inches in height. Cheap coal, brought by canal from Wakefield, endangered the profits of local mine owners. ‘The bald place upon my head is made by thrusting the corves’, said Patience Kershaw of the Booth Town Pit:

'My legs have never swelled, but my sisters' did when they went to mill; I hurry the corves a mile and more underground and back; they weight 3 cwt … the getters that I work for are naked except their caps … I would rather work in mill than in coal pit’ (33).

But an enlightened Board of Guardians did not allow the waifs of industrialism this luxury of choice; in 1842 children were still ‘apprenticed’ at the age of eight to colliers, some of whom take ‘two or three at a time, supporting themselves and their families out of their labour’. A sovereign was thrown in with each child for good measure (34).

A small, but growing, number of the younger men found steady employment as overlookers in the mills, or in a host of textile ancillary trades, or in the iron founding, engineering and wire drawing concerns of the town. But the experience of many must have been similar to that of Benjamin Wilson, the young Chartist who lived to become the historian of the local movement:

‘Tom Brown’s Schooldays would have had no charm for me, as I had never been to a day school in my life; when very young I … was pulled out of bed between 4 and 5 o’clock to go with a donkey 1 ½ miles away, and then take part in milking a number of cows … I went to a card shop afterwards, and there had to set 1500 card teeth for a 1/2d. From 1842 to 1848 I should not average 9/- per week wages; outdoor labour was bad to get then and wages very low. I have been a woollen weaver, a comber, a navvy on the railway and a barer in the delph that I claim to know some little of the state of the working classes … (35)

Living conditions conspired with working conditions to debase human life. The town’s brook, the Hebble, was a standing sewer; water was scarce and polluted; one twentieth of the population lived in cellar dwellings. A local surgeon, Dr. Wm Alexander, calculated that the

expectation of life in Halifax for “gentry, merchants and their families” was 55 years : for shopkeepers, 24: for the operative classes 22. One fifth of the adult deaths were 'unnecessary': for each death, there were 25 cases of sickness. The local Bounderbys attributed the high rate of working class mortality ‘to cheap Sunday trips on the railway or to drunkenness’. Dr Alexander countered by drawing up solemn balance - sheets to show that improved medical services would reduce the rates by reducing the number of pauper funerals (36).

On all sides conditions were such to brutalize. Economic parasitism flourished in every form: from the great Nonconformist and Liberal mill owner at the top, Jonathan Akroyd, through the intermediate levels of factors and agents, beating down the weavers’ wages, to the publicans and small tradesmen who owned the ‘folds’, or human warrens of damp mortar beside the Hebble (37), and the sub-contractors in the mines and the overlookers in the mills. With ghoulish foresight the children at Sunday school were encouraged to contribute their pennies to a burial society (38). The most common form of relaxation was to be found in the beer shops, thick in the town, well scattered on the uplands, where (in the apprehension of one anxious local gentleman):

‘the incendiary and the unionist fraternise together; from hence, under the influence and excitement of their too often adultereated beverage, they turn out at midnight … the one to fire the corn stack and the barn, the other to imbrue his hands in the blood of a fellow workman, or peradventure, the man to whom he was formerly indebted for his daily bread’ (39).

In the neighbourhood of the mills, infants of two and three ran around unattended, sucking rags in which were tied pieces of bread soaked in milk and water. Some of their mothers worked until the last day of pregnancy (40).

II

Visiting the town before the Reform Bill, Cobbett had been warned by a friend that ‘they were such aristocrats at Halifax, no one would come to hear me’ (41). They did come, of course: the meeting was crowded and enthusiastic. Despite Miss Lister’s belief that ‘the weight of property in the borough is decidedly Conservative’, the newly-enfranchised borough return two Whigs in 1832 with a radical runner-up and the Tory at the bottom of the poll (42). But Tory privilege was still a force to be reckoned with; landed families like the Listers had interests in coal, textiles, canals; the main local newspaper, the Halifax Guardian, was Tory; and, partly by dint of bribery and threats of eviction (43), the Tory candidate was assisted home against a Whig-Radical coalition in 1835 (44). In 1842 the Plug Rioters converged upon the town from both Lancashire and Bradford because (one speaker urged) 'great attempts would be made at Halifax, which was one of the most aristocratic places in the kingdom, to put down the people, and if Halifax were lost all would be lost' (45)

If the town had its aristocratic, it also had its revolutionary, traditions. Paine’s Rights of Man had been discussed in the cottages of many weavers and combers; a local Constitutional Society had struggled against the forces of ‘Church and King’; the reformers, never dispersed, had taken advantage of the Luddite agitation to give it – in this part of the West Riding – a revolutionary, as well as industrial, character (46).

Cobbett’s Register, the Black Dwarf , the unstamped press - including Hobson’s sheet The Voice of the West Riding - circulated widely in the area, there were men such as Robert Wilkinson (‘Radical Bob’), a shoemaker, and Ben Rushton, of Ovenden, the hand-loom weavers’ leader, whose record reached back into these years.

Perhaps it was Wilkinson who sat as the model for a sketch by a local essayist of ‘the village politician’. His library is a strange amalgam:

'There is the “Pearl of Great Price” and “Cobbett's Twopenny Trash”. The “Pilgrim's Progress” and “Flavell on Indwelling Sin”. “Baxter's Saints' Rest” and “The Go-a-head Journal” … “The Gentleman in Black” and “Howitt's Priestcraft”. “The Age of Reason” and a superannuated Bible

…'

He is a great reader, a close student of the French Revolution, an admirer of Bony. ‘It warms his old heart like a quart of mulled ale when he hears of a successful revolution, a throne tumbled, kings flying and princes scattered abroad … No work is done that week.'

'He recollects the day when he durst scarcely walk the streets. He can tell how he was hooted, pelted and spurned … and people told him he might be thankful ihe was not burned alive some night, along with the effigy of Tom Paine … He is very eloquent on the Manchester massacre and woe to the leather that is under his hammer when he is telling that tale … He tells queer tales about Oliver and Castle, and how one of them tried to trap him, and how it was “no go”’ (47).

Ben Rushton, the weaver, was no such comic period-piece, although he drew some of his vigour from the same radical soil. ‘As steady, fearless and honest a politician as ever stood on an English platform’(48), he was born in 1785 and had suffered at the hands of the authorities in earlier struggles for reform. Perhaps he had known the old Paineite, Baines, who was transported to Botany Bay for ‘twisting in’ Luddites (49).

Certainly he reminds us that Luddite prisoners sang hymns on the scaffold while waiting execution: and that there were riots in Halifax when the Methodist minister refused the victims sacred burial (50). A local preacher with a wide following, it is not clear whether Rushton was formally expelled by the Methodists or whether he severed the link himself: while a Chartist leader, he was in great demand, not only at Chartist 'chapels' and camp meetings, but also on formal occasions, such as the Sunday school anniversary in the weaving hamlet of Luddenden Dean, where he preached in worn clothing and clogs to a congregation wearing ‘their best clothes, namely clogs and working clothes, including long brats or bishops’ (51).

For such men as these, agitation for radical reform passed almost imperceptibly into Chartism. The Political Unions, which organised the campaign leading to the Bill of 1832, remained in being: that at Huddersfield was debating, in June 1833, 'Whether any good can arise from the present Shopocrat Constituency' (52). At Hebden Bridge and Todmorden (under Fielden’s leadership) these bodies supported the 10 hour agitation. It is likely that in these centres they became, after 1832, loose popular forums from which middle class support had been withdrawn. In Todmorden a Working Men’s Association was later formed, with Fielden’s support, which played an active part in the resistance to the New Poor Law before becoming identified with Chartism. In August 1839 a Todmorden magistrate was writing to the

Home Office of the WMA ‘it has as I conceive been the great cause of the agitation which prevailed in this District and should if possible be broken up (H.O.40.37). In Halifax there were several years of sharp political conflict before the strands of middle class radicalism and of Chartism were untwined. Michael Stocks, a local mine owner, who claimed to be the ‘Father of Reform in Halifax’ fought both Whigs in 1832 with a radical programme which carried the support of influential sections of the middle class, as well as winning the applause of the hustings (53). To the 10 Hour Bill he was opposed: but children under the age of 12 should not work in factories. “Household suffrage he would let alone till education was a little riper.” During the next three years causes of working class discontent were multiplying. Trade unionism, widespread not only in the textile industries, but also among miners, delvers, joiners, masons and others (54), was met by the united resistance of the masters, and the presentation of the 'document' in May 1834. The 10 hour campaign heightened tension between Radical mill-owners, like Jonathan Akroyd, and working people. The Tory Halifax Guardian was favourably disposed to factory reform (and, later, strongly anti-Poor Law), and stirred popular discontent with the Whigs skilfully.

In 1835 the 'Radicals' chose as their candidate Edward Protheroe, ex- member for Bristol, and formed an alliance with the Whigs (whose candidate was the sitting member Charles Wood) to fight the borough. Protheroe was a popular candidate: his defeat by one vote by the Tory led to a riot in the town (55). But he was in reality a political trimmer of the weakest kind, brought forward by those mill owners like Jonathan Akroyd and his son, Edward, who were seeking a reconciliation with the ‘aristocratic’ Whigs. Tension still existed between the local Whig caucus and the self-made men – Nonconformists and free traders in the main – who followed the lead of Baines in the Leeds Mercury : in February 1836 a row blew up over the appointment of magistrates, in which Whig bigwigs were denounced for 'hole in the corner' methods and for constituting a ‘grand, secret conclave, self-appointed, irresponsible … imperious and profound’ (56). But these skirmishes were little compared with the gathering resentment of rank-and-file reformers against the Whig Government and its local supporters, which first found full expression on the occasion of Fergus O’Connor’s first visit to the town.

O’Connor spoke in Halifax in August 1836 , presumably with the aim of encouraging the formation of a Radical Association to press his 'five points'. He was warmly received, and a Committee was formed at once with the immediate aim of securing his invitation to a projected dinner of the supporters of Messrs. Wood and Protheroe. At least two members of

the committee (Thorburn and Tetley) were later to become Chartists. The official joint dinner committee (which included, for the Radicals, James Stansfeld and Edward Akroyd) agreed to the proposal: but later, under pressure from the (Whig) Reform Association, rescinded the invitation.

O’Connor’s Committee then resolved to hold a rival dinner, as a gesture of protest against the influence of 'masses of property and superior intelligence … Whigism in Halifax is the same as Whigism in London (57)’

Edward Protheroe attended both dinners, but the real feast was enjoyed by the Tory Guardian. The Whig dinner was attended by Lord Morpeth and Edward Baines: its ceremonies were marked (to the delight of the Tories) by ‘inebriety’, ‘bacchanalian phrensy’ and ‘loathsome excesses’. By contrast, the Guardian was pleased to note the ‘moral propriety’ of the Radical proceedings at the Theatre. Of Protheroe, who attended both functions in order to plead the dangers of disunity which might endager his chances of success at the next election, it aptly remarked, ‘a gentleman less disposed to stand by his own opinions … we deny any man to find.’ At the Radical function he spoke in qualified opposition to the 10 Hour Bill, with qualified approval of the Poor law Amendment Act, and in qualified opposition of universal suffrage. It is not surprising that it was O’Connor who stole the thunder. On arrival at the town he was met by 'some thousands' in procession. In his speech he welcomed the disunity which he found: 'Are we so blind as we have taken ourselves from the fangs of one party, to present ourselves to another?”. He demanded universal suffrage, lashed the Poor Law, endorsed the 10 Hour Bill, attacked the state church and the Irish Coercion Bill. He spoke directly to the non-electors, solicited their support and won their applause:

‘You think you pay nothing: why, it is you who pay all. It is you who pay six or eight millions of taxes for keeping up the army. For what? For keeping up the taxes’ (Hear, hear and cheers) (58).

If O’Connor fanned the storm winds, the New Poor Law was the rock on which all further hope of political unity between Akroyd’s free traders and working class reformers foundered. The struggle in the North, which opened with the visit of Assistant Commissioner Alfred Power to Huddersfield in January 1837, led directly into the Chartist alignment of forces (59). The attempts to enforce the new Law came in a year of severe depression and bitter hardship for the hand-loom weavers, whose independent outlook and moral sensibilities were outraged. While Huddersfield and Todmorden were the centres of outright resistance,

feeling at Halifax was no less intense, though less skilfully led. A meeting of 'ratepayers' called to nominate Gurardians in February, 1837, ended in disorder after a resolution denouncing the Bill had been moved by Robert Wilkinson (the shoemaker) and William Thorburn. The nomination of Jonathan Akroyd was met with cries of ‘The greatest tyrant in the town’ and ‘We want no grinders – no enemy of the 10 Hour Bill’ . Michael Stocks, junior, the local Coroner, and other Radicals who supported the nomination of Guardians (on the grounds that the law of the land must be enforced) were shouted down as ‘renegades’ (60). A great public protest at the end of March was addressed by Oastler and chaired by Wilkinson: among local speakers were at least three local preachers who were later to become prominent Chartists – Ben Rushton, William Thornton and Abraham Hanson (of Elland). It is clear that the leadership of popular 'Radicalism' was now in the hands of local weavers and artisans: although, as the involvement of the rising carpet manufacturer, Frank Crossley (whose radicalism had more in common with that of Fielden than that of Akroyd) demonstrates, Halifax Chartists were always to carry with them some middle class support (61).

The general election of 1837 brought a very temporary revival of the old political alliance. O’Connor considered entering the contest, but in the end the Radical Association came in behind Protheroe:

' … a song ‘Protheroe is the Man’ was composed, and played by all the bands in the district and nearly every boy met whistling was almost sure to be whistling the tune’; his popularity appeared to be principally amongst the working classes' (62).

But Protheroe’s victory was little consolation. Oastler's repeated failure to secure election in neighbouring Huddersfield underlined the inadequacy of the 'shopocrat' franchise. The Poor Law struggle continued unabated. O’Connor maintained his links with the Radical Association, addressing a meeting in the Theatre in August, where he announced his plans for forming the Northern Star (63) The distress of the hand-loom weavers deepened towards the end of the year, and in the Hebden Bridge district assemblies of two and three hundred weavers waited upon the masters, demanding advances in wages (64).

In January 1838 a meeting was held of the ‘Halifax radicals’ which illustrates the fact that in towns such as this the various agitations which merged into Chartism - and which, for convenience, the historian may treat as separate and distinct, were often pressed forward by the same group of reformers – whether through Political Unions, Short Time

Committees, hand-loom weavers’ demonstrations, Radical Associations or other forms of organisation appropriate to the moment. The Chairman William Thorburn, announced the purpose of the meeting to be the discussion of a resolution that Parliament be petitioned upon the five Radical points – the ballot, universal suffrage, annual parliaments, equal representation and no property qualifications for M.P.s The resolution was moved by Robert Wilkinson and seconded by Ben Rushton, who argued that taxation without representation was 'no better than robbing a man on the highway' . When this resolution had been passed, a new Chairman was introduced – Ben Rushton – and the meeting went on to consider the question of the Poor Law. Rushton declared that 'he had been a common labourer for 33 years',

'and after having toiled for 50 or 60 years, he had the consolation of knowing that he might retire into a bastile and finish his existence upon fifteen-pence halfpenny a week. They who produce the necessities of life had a right to live, and if any person ought to suffer it was the idler' (65)

Thus, some months before the People’s Charter was formally drawn up, there existed in Halifax a vigorous local leadership, with its own organisation, promoting an agitation around the main demands of the Charter. From this it was a short step to a meeting at the end of July 1838 convened to oppose the Poor Law and to establish the Northern Union in Halifax. The meeting was addressed by Wilkinson, Thornton Robert Sutcliffe and others prominent in earlier Radical agitation. Ben Rushton moved support for the 'Birmingham petition'. O'Connor spoke in extravagant style: “When presenting the petition, we, five hundred thousand fighting men, demand justice at your hands. (Cheers)' (66).

Oastler, recommended ‘everyone before next Saturday night to have a brace of pistols, a good sword and a musket … It was the right and duty of every men to have them’ (67). In October Halifax contingent marched behind two bands to the first of many West Riding Chartist demonstrations at Peep Green in the Spen Valley. Robert Wilkinson, the Halifax veteran ('For twenty years he supported the glorious cause of Radicalism …') took the Chair for O’Connor, Stephens, Fielden; for Peter Bussey, the Bradford radical leader: for George White, the outspoken advocate of physical force: and for as well as for Abram Hanson and William Thornton, among local men (68). By December Chartism, as an effective force, was in being. The Halifax magistrates applied for additional troops; but the Home Secretary could not oblige – he had ‘no troops to spare’ (69). Before the end of the year, however, a letter from Colonel Wemyss, Assistant Adjutant General, announced to the Halifax Magistrates that he had been directed to station a Troop of

Cavalry at Halifax, and that a troop of the 3rd Dragoon Guards would arrive there on December 27th. Mr J.R. Ralph replied on behalf of the Magistrates that -

'The arrival of the troop is a source of great satisfaction to all respectable inhabitants and will, by the circumstances alone of it being known in the neighbourhood, give sufficient check to the ill disposed’ (70).

III

1839 opened with the annual dinner of the Halifax Radical Association at the 'Labour and Health' Inn, Southgate. Robert Wilkinson resigned as chairman, because of the pressure of 'other duties', although remaining a member of the Association. Ben Rushton was appointed chairman in his place. Speakers included Robert Sutcliffe, Abraham Hanson (whose son, Feargus O'Connor Hanson, must have been born about this time) Thomas Cliffe and James Tetley. Cliffe welcomed the improvement in trade – and especially in the 'gun trade'. The more moderate Tetley hastened to make clear that 'the political Union of Halifax have not provided themselves with arms'. They recommended radical prayer meetings to petition 'the King of Kings and Lord of Lords' to grant them universal suffrage (71).

Joseph Rayner Stephens had been arrested at Ashton-under-Lyne on 27 December, and Chartist localities in all parts of the north of England held meetings of protest. In the first two weeks of January meetings were held in Halifax itself (on New Years’ Day with 500 people present) and in Pellon, Mythelmroyd, Ripponden, Luddenden, Hebden Bridge and Stainland. At all of them resolutions of support for Stephens were passed, usually coupled with an endorsement of O’Connor. The Pellon radicals followed theirs with one in support of Richard Oastler 'though he is not the advocate of universal suffrage, yet we believe him to be an honest man, and as such commands our respect …' (72)

At Hebden Bridge the meeting affirmed the right of the people to have arms, and a week later another meeting in Halifax at the 'Labour and Health' followed suit and issued to the press a strongly-worded resolution:

'That we view with indignation the tyrrannical conduct of the Whigs and with the no less censurable conduct of Daniel O'Connell and the Sham Radicals, it being evidently the intention of both parties to lead or drive the country into a state of anarchy and confusion. We therefore resolve to all in our power to presrve peace, law and order; and while we are determined not to commit a breach of the peace, we are equally determined that others shall not commit a breach of the peace upon us

with impunity if we can avoid it by any means in our power. For this purpose we consider it to be both our privilege and our duty to be prepared to defend our persons and that of our wives and families, our

Country and Constitution, against open and secret enemies, whether foreign or domestic; and that while we venerate the memories of the Sydneys and Hampdens of bygone days, and eulogise the patriots of the present day, such as Feargus O'Connor, Joseph Rayner Stephens, James Bronterre O'Brien and others, we must view with mingled feelings of pity and contempt the willing and timid slaves who would lay down and let tyrants ride roughshod over them’ (73)

Already in January money was collected for 'rent' to be taken with the signatures to the National Petition by the delegates to the forthcoming National Convention of the Industrious Classes. The need for working class representation in the House of Commons was stressed by John Fielden when he reported to his constituents at Oldham on his attempts to introduce two measures. He had presented a petition signed by 6,000 handloom weavers, and had introduced a motion to improve their conditions, which was defeated by 73 votes to 12; a motion to repeal the New Poor law which had been seconded by Thomas wakley had been defeated by 309 to 17. Fielden's name was associated with that of O'Connor and Stephens by the Hebden Bridge Chartists at a meeting at which they adopted the National Petition.

The West Riding delegate to the National Convention Peter Bussey of Bradford – for many years the leading advocate of universal suffrage in the West Riding, and a man with a long record as a leader of the Short time and Anti-Poor Law movements. The Halifax Chartsits gave a dinner for him before he left for the Convention. He recommended ‘that every man before him should have a musket, which was a necessary article that ought to provide part of the furniture of every man's house. And every man ought to know well the use of it that he may use it effectively when the time arrives that requires him to put it into operation …’ (74).

When Bussey took his place at the Convention, he was able to take with him 52,800 signatures from his 'constituents', of which 13,036 were from Halifax, and £225 'rent',of which Halifax had collected £40. Money and signatures continued to be collected, and Halifax was represented regularly at the meetings held in the West Riding to co-ordinate the work and keep in touch with their delegate. The Northern Star listed six agents for its sale in Halifax and one in Ripponden. As well as the collection of 'rent' for the Convention, there was also money to be raised for the expenses of Stephens' trial. Both Rushton and Thornton preached sermons in many of the districts around Halifax to raise money towards what must have been a very considerable fund (75).

In February a town meeting called to consider Corn Law Repeal was triumphantly captured by Rushton, Wilkinson and Tetley, the Repealers, led by Jonathan Akroyd, retiring in discomfiture (76). The old radical alliance was finally shattered.

The Halifax Chartists were strongly O'Connorite: Major-General Sir Charles Napier was soon to describe Halifax as ‘wickedly Chartist’ (77). Even if there were more moderate counsels among the leaders, nothing could have held back the handloom weavers of the district from their preparations for insurrection. The Guardian, normally cautious and well- informed, reported at the end of March that 700 in the neighbourhood – chiefly the upland hamlets – were armed with muskets. At a public house in the weaving village of Midgley firearms

were being ordered (78). In April a Halifax magistrate was writing to Colonel Wemyss at Manchester:

'It appears that there are parties in various parts of our neighbourhood not only in possession of arms, but undergoing drill – though then without arms in their hands. These misguided people are the very dregs of the population and amongst them are many of the Hand Loom weavers who, of all classes of work people, have experienced the greatest privations and they are prepared to amend their condition at the expense of the community when called on by their leaders’ (79).

Napier was alarmed at the scattered disposition of the cavalry in the town; 'only 36 dragoons amongst the ill-disposed population of Halifax, with a man in billet here and his horse there.' He had information that there was discussion in public houses to plans to cut off the soldiers in their billets. Macerone's New System of Defensive Instruction for the People was circulating, barricades were being planned. The local authorities vacillated. In his first enthusiastic letter welcoming the troops, Ralph had written -

'I … gave instructions, in accordance with your wishes that the Billits (sic) for the Cavalry should be so arranged so to keep them as much concentrated as possible, under all circumstances …' (80)

But four months later, Napier was still not satisfied. He wrote sharply to Ralph, on 23 April:

'The times are critical and the magistrates must see as clearly as myself, that either I must withdraw detachments, or the civil authorities must find more compact quarters. The dispersed state of the detatchment in Halifax

(where 42 troopers are in 21 different quarters!) has called forth the necessity, on my part, of requesting that the magistrates will, if they wish the detatchment to remain, find some building in which the soldiers may be safe ..' (80)

In an even stronger letter to the West Riding magistrates dated on the next day, he expanded the same point -

'The cavalry at Halifax are quartered in the very worst, most dangerous way … Fifty resolute Chartists might disarm and destroy the whole in ten minutes: and believe me, gentlemen, that a mob which has gained such a momentary triuph is of all mobs the most ferocious' (81)

There were now two companies of the 79th Highlanders in the town, and one troop of Dragoons. The magistrates applied to Miss Lister for the use of some of her property, they took over the old dispensary. But some local employers preferred the cavalry to remain scattered and near at hand to defend their mills. For weeks argument raged; on May 10th Napier wrote again

'I am … sorry to say that I consider the troops in that town as a force incapable of making proper resistance in so feeble a position and therefore to be withdrawn upon the first appearance of danger … ' (82)

This may have have had the desired effect, for by October the magistrates were being asked to find separate accommodation for soldiers who were ill ‘in consequence of the great prevalence of the Typhus fever in the Town and neighbourhood and the crowded state of (the) house occupied as Barracks …’ (83)

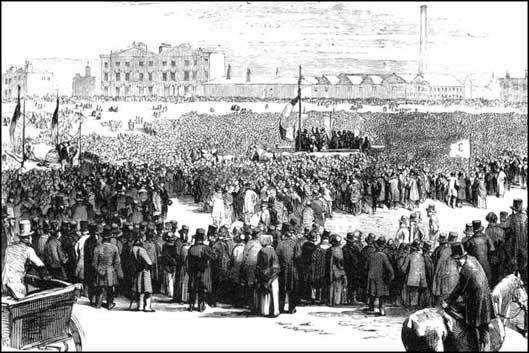

Whit Monday witnessed another great West Riding demonstration at Peep Green. Proceedings were opened with a prayer, led by William Thornton of Skircoat: ‘the sun shone on thousands of bared heads as he prayed that “the wickedness of the wicked may come to an end”’. With a characteristic gesture, O’Connor clapped him on the shoulder: ‘Well done, Thornton; when we get the People’s Charter, I will see that you are made the Archbishop of York.’ Other Methodist local preachers were well to the fore, Mr Arran from Bradford moving a resolution binding the meeting to 'not attend any place of worship where the administration of service is inimical to civil liberty … but to meet in such a way and manner in our separate localities in future as the circumstances of the case require'. He then, reported the Guardian,

‘spoke the most rank blasphemy, said that Christ was the greatest democrat that ever lived, that there should be no such thing as superiority or inferiority in the world, that they should cast the hypocrites (i.e. the Ministers of God who did not support Universal Suffrage) on their own resources, and they would then begin to bring forth the fruits of repentance' .

The resolution was seconded by Ben Rushton: 'For himself, he had given nothing to the parsons since 1821, and the next penny they had from him would do them good.' Hanson of Elland denounced the present sectarian preachers:

'They preached Christ and a crust, passive obedience and non-resistance. Let the people keep from those churches and chapels ('We will!') Let them go to those men who preached Christ and a full belly, Christ and a well-clothed back, Christ and a good house to live in - Christ and Universal Suffrage’ (84).

As in most areas, the Halifax Chartists were very much concerned with the possible danger of spies and provocateurs within their movement.

That there were some members, or close associates, in Halifax who were prepared to pass on information is clear from the Home Office and lieutenancy records. But it looks as though such men did have access to the inner councils, and that the Bradford agent, Harrison, probably did the Halifax Chartists something of a service by deliberately not involving them in his plans. In may a meeting at the 'Labour and Health' issued a resolution which had been passed unanimously:

'Resolved that the enemies of social order and good Government have their emissaries abroad, in order to prevent any member of the Radical Association from falling into the meshes of hired spies to apprehend, or cause to be apprehended, any person or persons who may be found recommending an organisation of physical violence, or any kind of training or drilling to the unlawful use of arms for the purpose of obtaining possession of our constitutional rights as Englishmen' (85)

The National Convention moved to Birmingham, and in July there were serious clashes in that City between the police and the Chartists. Some leading delegates were arrested, and tension mounted all over the country. Even the most determined opponents of physical force saw in the police attacks a justification for carrying arms. All over the country groups were discussing what ‘ulterior measures’ were to follow the rejection by Parliament of the National Petition. There is no doubt that some kind of armed action was considered in Halifax. A letter the vicar of Sowerby to

the Home Office complained that the Chartists ‘were going about from house to house amongst the respectable shopkeepers, inn keepers etc, threatening them if they will not support them.' A respectable grocer, who refused his contribution, had his name entered on a list ‘in red ink , as one of the first to be attacked when they rise’ (86)

A meeting in Halifax of the West Riding Chartists elected three 'supernumary' delegates to act if the present delegtes to the Convention should be arrested. Ben Rushton was elected top of the poll, followed by Samuel Healy of Dewsbury and Thomas Vevers of Huddersfield. The Convention had called for a ‘sacred month’ - a general strike of all labour to begin on August 12. In the discussions in the Convention and throughout the country, this proposal was coupled with the idea of an armed rising, as many believed that violence was bound to follow such action. But having made the proposal, the Convention later rescinded the order, and local branches were left to discuss their own 'ulterior measures'.

On the Thursday before the strike was due to take place, the Halifax Chartists met under the chairman ship of Robert Wilkinson to consider what action they should take. One of their members Thomas Cliffe, had already spoken on the subject to a meeting at Bradford – where he said

'It is a very difficult matter to restrain the people; they were anxious for the commencement of the Sacred Month on the 12th of August, but they must defer it for a short time; the country was no all prepared for it as they were. They were not so well prepared at Halifax …' (87)

But he urged all Chartists to continue to procure firearms (87). The Halifax meeting began with a unanimous vote in favour of Universal Suffrage, and then followed the discussion. Ben Rushton spoke of 'the seriousness of refraining from work in small numbers, as it might be, not for three days only, but for a much longer period ..' Some of the workers asked 'what they were to do for three days, for when they worked one day it was to earn victuals for the next'. Tetley, too, advised caution, and the meeting adjourned until Saturday. On the next day they met again, and the chairman announced that those who wanted to make a demonstration were to meet on Monday the 12th at 9.30 at the meeting room. Between 3 and 400 men assembled on Monday morning, to hear addresses by Cliffe, Sutcliffe, Rushton, Wilkinson and Tetley, and to adopt an address to the Queen (88). August ended with a parade and invasion with a parade through the streets and the invasion of the parish church.

For the next three months the public activities of the West Riding Chartists were much diminished. The curious events c0-incident with and following upon the Newport affair have never been satisfactorily explained. The arrest of Chartists throughout the country – though not in the West Riding – served to intimidate some and to make others cautious. At the same time there can be no doubt that some secret conspiratorial organisation was being built up. William Rider and George White of Leeds, Peter Bussey of Bradford, ‘Archbishop’ Thornton and William Cockcroft, a Halifax weaver, can be identified as the local leaders. Frank Peel, the historian of the Spen Valley, set down, at the end of the century, many recollections which fill the picture of nightly drillings and secret meetings in cottages and public houses (89). It is likely that some time before Frost's rising a delegate meeting was held at Heckmondwike to concert plans for a West Riding insurrection with the rest of the country (90).

According to firm tradition, Bussey broke down and hid at the critical moment before one projected rising. Ben Wilson, who had attended the demonstrations of 1839, although he can only have been fifteen years old at the time, says in his reminiscences that

'a meeting of delegates was held in Yorkshire to name the day when the people should rise; November of that year was fixed and Peter Bussey of Bradford was appointed leader … but, when the time came, Peter Bussey had fallen sick and had gone into the country out of the way or, being a shopkeeper, he was hiding in his warehouse amongst the sacks’ (91).

Wilson’s view is supported by an undated letter amongst the correspondence of the Halifax magistrates. Signed by Thomas Aked and James Rawson, it reports

'2 Houses taken by the Chartists of Nathan Smith that his their Meeting House the place his called the Street Queens head they was casting Bullets from Saturday night until Sunday Night the Day following Joseph Spencer says he as a pike and a Gun in is possession from the information we have received had not Peter Bussey been taken badly they would of commenced the same day that Frost did’ (92)

By the first week of January, Bussey was on his way to the United States, and the ballad singers in the district sang:

‘I’ve heard Peter Bussey Has fledged and flown; Has packed up his wallet,

And left Bradford town’ (93).

There seems to have been no attempt at all made at an uprising in the West Riding at the beginning of November. Whether, as Wilson and the Halifax Chartists seemed to think, this was due to the defection of Bussey and other leaders, or whether there never was a national plan, is not clear.

James Stansfeld, later to become M.P. for Halifax and in 1839 a student with Shelleyan and Chartist sympathies, wrote from Halifax to a friend in London that Newport -

'was an affair of combination through a great part of the kingdom … That secret organisation was going on to a great extent I knew before as far as this neighbourhood was concerned. It was known here (among the Chartists alone, of course) when the attack was to have been made; if successful a similar movement would have been attempted here. As it was there was some foolish thoughts of it. It would however … have been quelled immediately, as the magistrates on information received had sworn in special constables and had already a large military force stationed here. So you see the spirit has not subsided and the materials are good for a riper time’ (94)

There was considerable discussion in the Chartist press and in Chartist reminiscences in later years about the events of November 1839, but so far it has not been possible to build up anything like a clear picture from the conflicting accounts.

The events at Newport and the arrest of Frost Williams and Jones were a tremendous shook for Chartists all over the country. Reports from the magistrates in Halifax to Colonel Wemyss give some idea of the confusion that followed the failure of the Welsh Rising. A letter dated Nov. 12, 1839 reports:

‘There is a large meeting room in this town used by the Chartists for their meetings, their purpose being covered by sermon reading and psalm singing, but where the Committees sit and transact their business - last Sunday evening my informant went out of curiosity and got admittance

and stayed there about three hours. Fifty persons or thereabouts were present, mostly strangers with a few townspeople … After much talk, a leader well known here directed to write to the Chartist Secretaries throughout the West Riding to gather opinions as to their best mode of proceeding. - From the expressions of the speakers, their idea is to “go to work” (meaning an outbreak for the purpose of plunder) and to do it in a better fashion than it had been done in Wales, where they consider it to have been sadly mismanaged. It was also said that they might as well fight “to death” as be starved “to death” … Their plan as respects this town appears to be that one of the out-townships (Ovenden, which is the worst of them) is to send its force to join friends here, and the others are to march to Bradford’

In the out-townships the weavers were busy 'grinding their Pikes and casting Balls.' A week later (20 November) a witness reported that he had been -

'a few nights ago in the company with one of the Chartist leaders, named Thorburn (95), who was at the time a little intoxicated, and talking of the state of the people, Thorburn aid, that Chartism was now at a very low ebb, that on last Wednesday night all their books and papers were burnt.'

But a month later (25 December) Wemyss was still receiving reports from the office in charge of the Halifax troops of secret preparations: the Chartists 'are told off by squads, and have their leaders for each squad, and there are numerous meetings, termed Tea Parties constantly going forward' (96).

Early in December James Harrison, the agent who was reporting regularly on the activities of the Bradford Chartists, told the magistrates of a visit to Queen’s Head Chartists, in the company of George Flinn, of Bradford Curiously Harrison told the magistrates that he did not know the name of the local men apart from Flinn himself About a dozen men were at the meeting -

‘One of the speakers said we have made up our minds and sent our determination down to Bradford – we'll have no more public meetings nor pay no more money – we have 260 or 270 men well armed and ammunition is ready at any time by the sound of a horn ...’

After the meeting, they adjourned to the bar of the local inn, where they met a delegate from London, who -

'looked earnestly at me and asked Flinn if he knew me – Flinn said he had known me for three years and that I was as good a man as any in the room – this delegate said his reason for asking that was that he was aware there may be sies up and down the country …'

Harrison reported that the Bradford Chartists were waiting for a signal for a general rising. A delegate conference was to be held in london, a new Convention, on December 19th, and a lead was to come from it. The Bradford delegate was to be John Hodgson -

'Both Hodgson and Flinn have told me that the general rising is to take place upon receiving information from London but that they expected it would be about the 27th, four days before Frost's trial – Hodgson also told me that in the convention a place would be settled to meet the judges and to shoot them in their carriages on their way to Frost’s trial but that was to be settled by the convention in London'' (97).

There were no signs of any activity in Halifax or the villages around on Dec. 27th. On the night of 11 January 1840, after the news that Frost had been found guilty, armed Chartists occupied Dewsbury, Heckmondwike and Birstall, and a special constable found the road between Bradford and Halifax ‘completely filled with men, having torches and spears with them’. (98)

Later in January Bradford was the scene of another attempted rising, led by Robert Peddie, a Scot and stranger to the district. The whole story of the events in Bradford has not yet been pieced together, but it would seem that Harrison, who was without doubt at the centre of the whole exercise, had been entrusted with the task of notifying neighbouring Chartist groups, including those at Halifax, of the plans, and had failed to deliver this message. If this was so, he probably saved some of the Halifax men from being prosecuted, for the Bradford men were easily rounded up, and their leaders imprisoned.

The Halifax magistrates were worried in case the troops stationed in the town might be moved, and the town left unprotected. Mr J.R. Rhodes wrote to Colonel Wemyss on 28th January, asking for reassurance that the Commanding Officer of the troops would be responsible to the Halifax magistrates and not liable to answer a requisition from another district.

He referred to ‘the Bradford affair of the night before last’, and declared - ' … We are still in a state of uncertainty as to whether we shall be visited by the mischievous banditti around us, and are consequently on the alert. If, however, the military force should be drawn off to a disturbance, such

circumstances would be immediately made known to the disaffected. In the present temper they might take advantage of the opportunity and in a short time do a vast deal of damage, which now seems to be their main object … ' (99)

IV

The leaders of the Halifax Chartists had not been arrested, and the local movement had not lost face as it did in Bradford and some other West Riding localities. The main preoccupations of the movement nationally was the attempt to secure pardon and release for the leaders of the Newport rising, and in the West Riding the Chartists of Halifax took the lead in discussions of this question. At a delegate meeting in Manchester at the beginning of February, Thomas Cliffe of Halifax took the chair on the first day. He opened the conference by saying that

'his constituents were willing to do anything to serve the prisoners, but was of opinion that harsh measures and expressions would injure them ..'

David Hitchin, also from Halifax, confirmed Cliffe's statement 'and would merely add that the people would sacrifice life itsef to save the prisoners from transportation' William Thornton was present, representing Bradford – e had presumably moved there from Halifax. During the discussion, he mentioned by name a police agent, Greensmith. Cliffe said that he had once lived seven doors from this man, who was ' a drunken fellow and had been confined six months for thieving.' The magistrates, Cliffe said, paid the agent ten shillings a week, but none of this went to his wife, who had to go begging.

The result of the Manchester conference was a memorial to the Queen, and an address signed by all the delegates calling for signatures to the memorial. In March another conference was held on the same subject. Halifax was represented on this occasion by James Rawson. This is the same name as the informer whose letter is preserved amongst the Halifax magistrates' papers. Rawson is however an extremely common name in Halifax, and there is no indication that it is the same man. But it is not impossible, in the light of experience in other districts, that Rawson could have been at the same time a trusted and active Chartist and an informer. The one note which remains with his signature is not, in fact, a particularly damning one, and it contains only information which must have been fairly easily obtainable. The authorities obtained their information about the Chartists from a wide range of informants, ranging from criminals of Harrison's type (he was finally transported some years later for horse-stealing, which he had treied to make doubly profitable by informing against two young boys for his own crime) through vaguely

disreputable characters like Greensmith, whose access to information must have been minimal, professional police officers actually planted, as in Birmingham, who sometimes informed on each other, to Chartists, driven either by poverty to betray their associates, or by principle to inform on their opponents within the movement. Thus James Rawson could have been a Chartist who was worried by the 'physical force' preparations which he reported, or one so poverty-stricken that he made his fairly typical report for the reward. Since his report was never used in public evidence, he could perfectly well have continued his association with the Halifax Chartists. But there is in any case, no proof that it was the same man. At the Manchester delegate meeting, Rawson said his constituents were opposed to any more petitioning, but that 'something or other must be done'. They proposed using 'Bronterre O'Brien's plan'; this was the proposal to use the machinery of elections and other public occasions to bring the Chartist case before the public. Bronterre wanted Chartist candidates on all the hustings and the Chartist case to be put at every towns-meeting or other public meeting, whatever its purpose. But when the delegates should have re-convened in Manchester a month later to discuss the progress of the campaign, only two areas besides Halifax were represented, Leicestershire and Nottingham.

At this April conference, Cockcroft represented Halifax, and chaired part of the meeting. He again proposed O'Brien's plan, and said that the Halifax Chartists were as determined as ever to take 'every positive step' to obtain the Charter; 'things' he went on 'did not seem so bad in Halifax as in Leicester and Nottingham, but trade was bad, and the average earnings of many n work did not exceed 7/- per week' (101)

1840 a year of reorganisation and consolidation for Chartism. The character of the movement changed dramatically after the intense excitement of the mid-winter months. It was in the summer of 1840 that the National Charter Association was formed. The Halifax branch was formed some time during 1840, and by early 1841 Halifax and twelve branches in the out-districts made up a ‘District’

of the NCA (102).

In March 1840 the Chartist meeting and news-room, with their books, papers and banners, was burnt out (103), was burnt out. But meetings continued. In May, James Rawson chaired a delegate meeting of the Halifax groups. He reported that a large worsted manufacturer, James Aked Junr. Had reduced weavers' wages from 8-10%. He recalled that two years earlier a deputation had forced the same man to give up a similar reduction, but on this occasion a deputation had had no success.

'Aked is chief constable of the township, Midgley, a great enemy of Chartists, a liberal Whig, a Corn Law repealer, and a great friend to the New Poor law and Bastille system' (104).

In June a public meeting was called, protesting against the treatment of the Chartist prisoners. Ben Rushton warned defectors

'Every labouring man who gave up the principles of the Charter ought to be made to crawl upon his belly to the aristocracy all the days of his life, and be fed as they are fed at the bastille' (105).

Before he himself was imprisoned Feargus O’Connor had proposed that money should be raised for the Chartist prisoners by adding 1/2d to the price of the Northern Star. This additional 1/2d was to be nothing to do with him, but was to be administered separately by a committee, which was to include Robert Wilkinson from Halifax. In the course of recommending the proposed increase, it was suggested that readers might find the money by buying a gill less of ale a week. Robert Sutcliffe answered this suggestion in a furious letter to the Star -

'Good God! To tell starving men, who cannot afford to get a gill of ale in one month, no, nor in six months, and whose table is not graced with half a pound of meat during that time … is a tantalising and trifling with their poverty and misery' (106)

Nevertheless all through the year Wilkinson, as treasurer, continued to send donations to the funds for prisoners’ families. In June the Odd Fellows Hall was opened in Halifax, an enormous building with rooms of all sizes and a large meeting hall. After this there was no problem of a meeting place for the Chartists, however popular the speaker.

As in other parts of the West Riding, agitation for factory reform and against the New Poor Law continued to be part of the Chartist activities. The Tory Halifax Guardian supported them in these campaigns. The general Election of the summer of 1841 brought about a curious alignment in the town. Protheroe, by his support for the Poor Law, had forfeited all Chartist support; and one J. Gully Esq., late member for Pontefract, came forward as a Radical and Anti-poor law candidate against both Protheroe and Wood. A meeting of 3,000 non-electors, called by the Chartists, gave him support. At the last moment Gully retired. The Chartists attended the hustings in force, and the Liberal candidates underwent a severe questioning from John Crossland, a member of the hand-loom weavers’ central committee, demanding to know why no action had been taken to relieve their plight.- Wood’s

defence – that the only measure that would benefit the weavers was the abolition of the Corn Laws – was shouted down with cries of ‘I wish thou were brought down to be a handloom weaver’. Ben Rushton took the field to question Protheroe. The Chartists (he said) had been 'gullied':

'In all the speechifying I observe that we have plenty of gold and silver like the stones of Jerusalem streets, and leaves as large as Goliath and Gath (Laughter). They never told us that as trade increases, they will increase their machinery. Machinery is the standard of the hand-loom weaver, and in many cases of the woolcomber, for they now do the work with a woman and child, and take the labourer to a new scientific resistence'

The Chartists advised support for the Tory candidate, Sir George Sinclair, a strong advocate of factory reform and an opponent of the New Poor Law. In the event, Protheroe and Wood were once again returned (49).

The work of the local association was encouraged by O’Connor’s release from prison, which was announced by the Chartists through the public bellman. His visit to the town early in December was the occasion of a triumphal demonstration. A report in the Star described the local movement as ‘progressing most gloriously … Numbers are coming forward to enrol their names in our Association’ (108). The work which

had been put into consolidating organisation brought returns when the local Chartists engaged in the collection of signatures and money for the Second Petition in the early months of 1842 .(109)

V

While trade was stagnant in the cotton industry, it was good and even brisk in the worsted industry in August 1842 when the Plug Riots commenced (110). The strikers flowed through the valleys from Lancashire into Yorkshire, gathering support from the Yorkshire hand- workers on the way. Whereas in Lancashire the original impulse behind the strike was primarily industrial, in the West Riding towns the local Chartists responded to the call of the Manchester delegate meeting of the N.C.A., calling out all workers in support of the Charter. Placards were posted in the upper Calder Valley and elsewhere:

'Englishmen, the blood of your brethren reddens the streets of Preston and Blackburn, and the murderers thirst for more … The cotton-workers have taen the lead in declaring for the Charter. Follow their example … Intelligence has reached us of the wide-spreading of the strike, and now within forty miles of Manchester every engine is at rest; and all is still, save the miller's useful wheels, and the friendly sickle in the fields.

Strengthen our hands at this crisis; support your leaders; rally round our sacred cause, and leave the rest to the God of Justice and of battles (111)

Response in the West Riding varied. At Bradford the local Chartists seized the initiative, stopping most of the mills before the Lancashire strikers arrived. At Huddersfield the leaders were described as being -

'all strangers, evidently in humble life – sensible, shrewd, determined, peacable … the burden of their speeches was to destroy no propert, to hurt no human being, but determinedly to persist in ceasing from labour and to induce others to do the same until every man could obtain “a fair day's wages for a fair day's work”' (112)

'The Native operatives are quiet, but evidently wish success to what may be called an insurrection' (113). At Dewsbury support for the strike was complete, but the strike was halted on the western environs of Leeds, in part by the exertions of the authorities, in part by the indifference of the working population.

The strikers converged on Halifax from both Lancashire and Bradford, the main body of strikers crossing the Pennines from Rochdale into Todmorden on August 12th. The next day they moved up to Hebden Bridge, closing all mills, drawing the plugs from the boilers and letting off the mill dams on the way. While some of the strikers returned each

night to their homes, the crowd was swelled at each stage by local workers. At Halifax 1302 special constables were sworn in, at Hebden Bridge 170.

Contemporary accounts, as well as reminiscences, provide a vivid series of pictures of the events of the next two or three days. At dawn on August 15th an excited crowd – hearing that the approach of the strikers was imminent – assembled on Skircoat Moor. Ben Rushton addressed them, condemning the masters who had reduced wages 'for the purpose of obtaining the repeal of the Corn laws', urging people to support the strike and keep the peace. Upon the magistrates intervening to disperse the meeting, the crowd formed itself into a procession ' and marched towards Luddenden Foot to meet the Todmorden and Hebden Bridge turn-outs on their way to Halifax' (115). Some mills were stopped on the

way; the handloom weavers who joined the strike threw their shuttles into a common bag, depositing it in a public house.

‘It was a remarkably fine day, the sun shone in its full splendour, one eye witness recalled. ‘The broad white road with its green hedges … was filled with a long, black straggling line of people, who cheerfully went along, evidently possessed of an idea that they were doing something for a betterment.'

When the contingents met, ‘Ben Rushton stepped aside into a field and led off with a speech … Before the speaking a big milk can was obtained and filled with treacle-beer’. Some went into adjoining houses and helped themselves to food.’ (116)

In the late morning they entered the town in a procession about 5000 strong singing Chartist hymns and the 100th

Psalm (117).

'The women went first, and were followed by a long procession of more or less pretensions. They then dispersed, under orders given by a man on horseback, who told them what mills to visit’. (117)

Meanwhile, a formidable contingent, 4000 or 5000 strong, were approaching the town from Bradford:

‘The sight was just one of those which it is impossible to forget. They came pouring down the wide road in thousands, taking up its whole breadth – a gaunt, famished-looking, desperate multitude armed with

huge bludgeons, flails, pitch forks and pikes, many without coats and hats, and hundreds upon hundreds with their clothes in rags and tatters. Many of the older men looked footsore and weary, but the great bulk were men in the prime of life, full of wild excitement. As they marched, they thundered out … a stirring melody … (119)’

Despite the efforts of the soldiers, the two contingents joined forces. The Riot Act was read, and a sharp skirmish took place between the military and the crowd before the main body dispersed – only to separate into smaller groups which closed down the remaining mills, including the largest mill of Akroyd’s which the magistrates had been at great pains to defend:

‘The thousands of female turn-outs were looked upon with some commiseration by the inhabitants, as many were poorly clad and marching barefoot. When the Riot Act was read … a large crowd of these women, who stood in front of the magistrates and the military, loudly declared that they had no homes, and dared them to kill them if they liked. They then struck up the Union Hymn:

Oh! worthy is the glorious cause, Ye patriots of the union:

Our fathers’ rights, our fathers’ laws Demand a faithful union.

A crouching dastard sure is he, Who would not strive for liberty, And die to make old England free From all her load of tyranny,

Up, brave men of the union’ (120).

In the skirmishes a number of prisoners were taken by the military and the special constables, and several attempts at rescue were made. Food was handed out of doors and windows to the strikers, who at length made their way to the moor above the town, where they were further speeches and prayers, and where a number slept in the open air.

The Specials, it seems, had drawn upon themselves both ridicule and odium during the day. They had consumed an enormous

quantity of gin. Among their exploits were listed the capture of a sweep and the town’s bell man. Their valour was displayed mainly in breaking the heads of the women: one was compared to a ‘pair of tongues on horseback’.

One at least, to his credit, auctioned off his staff in disgust. (121)

By contrast, the behaviour of the strikers was restrained and even at times good-humoured:

'I have heard it said that there was much plundering at Halifax, but I saw none; although there might have been a baker’s shop or two entered, that would be the full extent’ .(122)

On the next day events took a more bitter turn. The story is best told by

F.H. Grundy, a civil engineer and friend of Bramwell Bronte, who was engaged in railway construction and had an office at Salterhebble on the Halifax-Wakefield road, just outside the town. On the morning of 16 August he found the road ‘like a road to the fair or to races … all busy - women as well as men – in rushing along the various lanes over my head with arms and aprons full of stones’. The mob were preparing to intercept the Omnibus conveying the prisoners of the previous day – with a military escort – to Elland railway station on route for Wakefield. The convoy passed through before their preparations were made, and the people determined to ambush the soldiers and magistrate on their return. Grundy decided to warn them, and attempted to leave his office on the excuse of paying a routine visit to the railway bridge:

'I have hardly got a dozen yards from my door when heavy hands are on my shoulders, and I turn to see two of my own men.

“Thou munnot go t'ut brigg to-day, sir” “Why, what nonsense is this?'

'We be main sorry, sir, varry, but thou mun come back agean. Thou'rt to go whoam into t'house, and we two are to watch thee, like.

Thou'lt nobbut be murdered, and then cannot do ony guid. There are a matter of fower thousand folk looking on; so coome sir. Thou’rt not to be fettled, but thou’rt to kept inside o’ t’house’.

At length the soldiers and the omnibus returned:

‘They slow into a walk as they breast Salterhebble hill. Then a loud voice shouts, “Now, lads, give it ‘em.” From every wall rises a crowd of infuriated men, and down comes a shower of stones, bricks, boulders, like a close fall of hail ... “Gallop! Gallop!” comes the order, as their leader spurs his horse up the steep hill. But the men, jammed together, cannot gallop. They come down pell-mell, horses and riders. Those who can get through ride off at speed after their officer … Then the command came,

“Cease throwing”. Eight horsemen, bleeding and helpless, crawled about the road, seeking shelter. Down come the hosts now, and tearing the belts and accoutrements from the prostrate hussars, the saddles and bridles from the horses, they give three cheers and depart … (123)’

A report was sent express to Leeds, with an urgent demand for more troops:

‘A most terrible affair has occurred at Salterhebble, and at the time I write it is feared there will be many lives lost before the day is over. I scarcely know how to inform you in a few lines the dreadful state of things in Halifax and the neighbourhood. The town presents an awful state of things …

' The military are all out, and the special constables, too; the mob are at Skircoat Moor, and it is said here at the Northgate Hotel that they are expected down shortly when the military will, I am positively assured, receive instructions to fire …

All the mills are closed. Mr Akroyd (I have seen him) is quite overwhelmed in difficulties. The mob keeps him at bay, and he has had his premises completely barricaded’ (124).

William Briggs, a local magistrate, and Mr Barker, of the Northern Star, were among those injured in the omnibus.

The soldiers were not slow in taking their revenge. They sallied forth from the Northgate Inn in strength, and a good deal of indiscriminate firing took place. 'A man coming to his door to see what was the matter, was shot dead'. The main body of rioters was ridden down by the hussars, who 'followed the flying people for miles … Many a tale of wounded men lying out in barns and under hedges was told’ A report in the Home Office papers listed 8 wounded, 4dangerously. Two at least of these men did not recover. (125)

The authorities pursued their advantage vigorously. Leading mill owners issued a notice urging all masters to re-start work, ‘furnish their workmen with arms’ and seize any persons found ‘skulking about their premises’ (126). The strikers appeared to lack central leadership: although the local paper reported that a group of men were seen at one time releasing carrier pigeons. Ben Rushton, who had been taken into custody, was released when the agitation subsided. (127). The strike spread to the West, but by 19 August many of the mills in Halifax were back at work. Thirty-six prisoners were sent to trial, and several received severe sentences –

including one of transportation – for their part in the riots. By 12 September the clerk to the Halifax magistrates was able to report ‘business … carried on as usual with the most perfect order and security.'

(128) The local satirist was able to address the 'scum of society', 'the 'many-headed plug-drawing public':