"Get up, Arthur, today is revolution!!"

It is often overlooked that the insurrectionary demonstrations in Germany's November 1918 Revolution were largely made up of women who worked in the munitions factories or the home (and often both). Cläre Casper-Derfert was a factory worker and the only woman of the Revolutionary Stewards. This is her account of the November Revolution.

Cläre Casper-Derfert

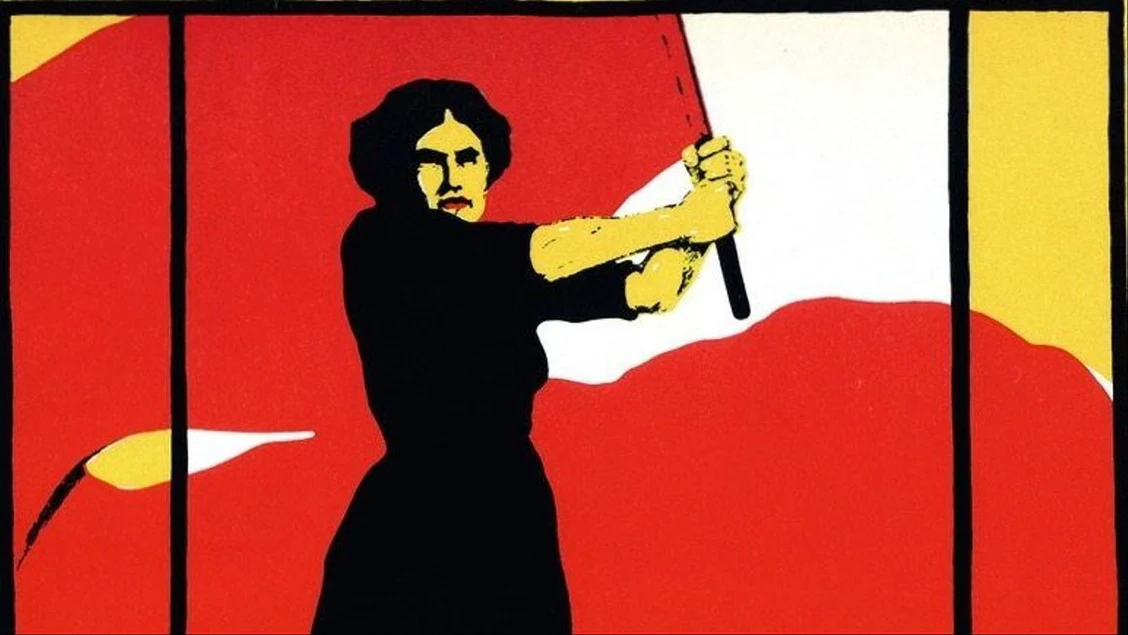

When we think of the November Revolution in Germany in 1918, we often picture men with rifles and red flags. But the insurrectionary demonstrations were largely made up of women who worked in the munitions factories or the home (and often both). Some of the revolution's most well-known leaders were women, including Rosa Luxemburg, Luise Zietz, and Clara Zetkin. But the masses of women workers have largely remained anonymous.

Cläre Casper-Derfert was a factory worker and the only woman of the Revolutionary Stewards, the secret group that organised the Berlin uprising. Her recollections, published in 1958, have been quoted by numerous historians, including Ralf Hoffrogge, William Pelz, and Klaus Gietinger. Casper-Derfert was hiding 400 guns (!) in her apartment, yet Berlin police simply could not imagine that a woman would be involved in such dangerous activities. At the same time, it's interesting to note that she was making sandwiches for her comrades while also transporting weapons.

This account, in English for the first time, originally appeared in the collection "Vorwärts und nicht vergessen!" (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1958) which was published in East Berlin on the revolution's 40th anniversary. These eyewitness reports are valuable, yet need to be read with a certain degree of scepticism, as they were written and edited according to the needs of the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Certain historical figures have disappeared from all the accounts: Casper-Derfert, for example, refers to an anonymous "head of our illegal organisation" who is presumably Richard Müller.

For more on women in the November Revolution, see chapter 7 of Bill Pelz's People's History of the German Revolution 1918-19 (London: Pluto Press, 2018). For a dissection of this and similar reports in German, see Anja Thuns, ‘"Cläre, mach’ Du’s!" Erinnerungen von Frauen an die Revolutionsereignisse 1918/19’, In Bernd Hüttner / Axel Weipert (Eds.), Emanzipation und Enttäuschung: Perspektiven auf die Novemberrevolution 1918/19 (Berlin: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, 2018), p. 55-61.

Even after four decades, the irrepressible joy of revolution shines through in this account. Casper-Derfert leaves out at least one important detail, however: Her comrade Arthur Schöttler was brutally murdered just two months later. On January 11, 1919, the 200-300 workers occupying the Vorwärts building in Berlin were forced to surrender to the proto-fascist Freikorps. They sent out seven negotiators, including Schöttler, with a white flag. These seven were taken to the Dragoon Barracks and beaten to death. Rosa Luxemburg references this horrific crime in her final article.

***

I had to start working when I was seven. I ran errands, helped out in the household, and — though still a child myself — took care of the kids of so-called "better" people. At 16, I began working in a factory.

In the Berlin lightbulb factory Schmidt & Kompanie in the Chausseestraße, I joined the German Metalworkers' Association (DMV). Back then there were many economic struggles against the bosses. I took part in strikes and lock-outs. Since I always stood up for the interests of my colleagues, I was often reprimanded and thrown out onto the street by the capitalists. One of them said in court: "An extremely intelligent and capable worker, but impossible to have in the factory due to her agitation." In this way, I passed through a number of Berlin factories and became quite well-known in the Berlin metalworkers' movement.

At Goerz, a manufacturer of optical devices, I joined my first political strike, when we Berlin workers — men and women — protested against the conviction of Karl Liebknecht. That was in 1916. In April 1917, during the so-called "bread strike" which was in protest against a further cut in the bread rations, women were particularly active. After all, every cut in rations was especially bad for working women, who generally had a household and children to look after as well. After three days, our strike was broken off by the union bosses. But the revolutionary spark could no longer be extinguished.

When we learned, in November 1917, that the Russian workers had finally thrown out their oppressors, the Berlin factories became rebellious again. The workers at the Dr. Paul Meyer factory spontaneously demanded an assembly. No speaker showed up, so the workers said: "Cläre, you do it!" I had no experience giving speeches, but I gathered my courage and spoke about the workers' situation: the misery, the hunger, the suffering of so many who had been killed or crippled. As a solution, I proposed: "Do as our Russian brothers did! Put an end to the war! The sun is rising in the East!"

From then on, we went to the union assemblies as a revolutionary opposition, and confronted the union bosses without holding back. The Social-Democratic Party leaders, and also the Cohens and Sierings of the German Metalworkers' Association, were pursuing the most fanatical policies to persevere and prolong the war, against the will of the workers. The masses' rage in the face of war and hunger grew and grew.

By January 1918, the time had come again. News about the workers' fighting mood was coming out of all the munitions and arms factories. At a meeting of the lathe operators from different factories, on 27 January 1918 in the musicians' halls in the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Straße, the Revolutionary Stewards gave the signal to begin the struggle. All workers were called on to walk out of the factories the following day, and to force an end to the war with a political mass strike. An Action Committee was elected including, among others, ten representatives of the Revolutionary Stewards and me as a representative of the women metalworkers.

Roughly 500,000 munitions workers joined this strike in Berlin — mostly women who had replaced the men serving at the front and who, as semi-skilled workers, were earning low wages while creating enormous profits for the arms industry.

By 29 January, all assemblies were banned, and on 30 January, the union hall was occupied. The masses poured into the streets. On 31 January, there were huge demonstrations all over the city. The police, on foot and on horseback, attempted to disperse them and opened fire on the crowds of workers. But we regrouped in the side streets and did not make it easy for the police. That very day, the imperial government declared an aggravated state of siege and convened extraordinary courts-martial. The police were reinforced with 5,000 non-commissioned officers from the army. On 1 February, the militarisation of large factories was proclaimed. A number of revolutionary workers' leaders were arrested, including Leo Jogiches, the organisational leader of the Spartacus group.

The government, supported by the "civic peace" politicians of the Social-Democratic Party and the reformist union leaders, tried to stop the strike by all means. To this end, these politicians also joined the Berlin strike committee; this included Ebert and Scheidemann, who at the Magdeburg Trial in 1924 boasted: "Had we not joined the strike committee, then this court would not be sitting here today." Today I still remember exactly what a pathetic figure Scheidemann cut in 1918.

As a member of the Action Committee, I organised a demonstration of the Charlottenburg workers in the Kleiner Tiergarten, a small park in Moabit. Scheidemann was standing on the Schlossplatz in Charlottenburg and was supposed to speak. We all went down the Kaiserin-Augusta-Allee together, and our demonstration got bigger and bigger. But our hope that Scheidemann would speak to the workers was in vain. He categorically refused.

On 3 February, the strike was approaching its end. Hundreds of people were sentenced to long prison terms, and thousands were drafted into the army under the code word "coal," with most of them sent to the front lines.

In the Metalworkers' Association, the deputy chairman Wilhelm Siering, speaking to the women workers' commission, accused me of being partially responsible for the suffering caused by the strike. I replied that his policy of perseverance had caused far more suffering. It was my unshakeable conviction that we had to use every means — including our lives — to fight against the warmongers.

On 1 February 1918, during the strike, Luise Zietz recruited me to the USPD. As I feared no danger and no sacrifice, I was also accepted into the circle of the Revolutionary Stewards. I am particularly proud that I was the only woman who served on this committee. The illegal work was now intensified.

The experiences of the January Struggle had taught us that it was necessary to arm the masses. In the summer of 1918, we got in touch with comrades from Suhl, and they helped us obtain weapons for Berlin illegally. I had a small apartment in Charlottenburg where I lived alone, and I immediately agreed to help out with this important and dangerous task. Weapons were delivered to my apartment. Two reliable young comrades, Arthur Schöttler und Fritz Schwerdfeger, repacked them in small boxes with sliding lids, and transported them with a wagon to particularly trustworthy comrades in the different districts of the city.

Usually, Arthur Schöttler would arrive early in the morning with a horse and cart he had rented in Reinickendorf. While the wagon stood in front of a bar a few doors down, we would take a map of Berlin from my apartment and look for the shortest route to every delivery point. After each successfully completed trip, we were happy to have gotten one step closer to the revolution we were longing for. We were all young and full of enthusiasm. It would not have occurred to any of us to demand a penny's worth of wages for this dangerous work.

Gradually, however, my neighbours took notice of the many heavy crates being moved, and on 1 November 1918, I received a summons from the Department IA (the political police back then) to an interrogation. I was terribly frightened — I had 400 pistols and 20,000 rounds of ammunition stored in my apartment. Fortunately, I had enough boxes on hand, so I took all the pistols out of their little cartons and packed them tightly in the boxes, and burned all the cartons in the oven. Then I waited anxiously for Arthur and Fritz. Finally, our delivery men for weapons arrived. I showed them the summons, loaded the heavy boxes onto their backs, put a sandwich in the coat pocket of each of them, and chased them out of the apartment as quickly as possible. Now the two of them had so many "goods" on their wagon that they did not know where to store them. A large part was deposited with trusted comrades, and the rest was left in the wagon, carefully covered and pushed into the shed. The next day, these weapons were also stored safely.

Thus, the biggest danger was eliminated, at least for the time being. But about 7,000 rounds of ammunition had not fit into the boxes. I put them into two parcels and took those separately to comrades living farther away. My apartment was finally "clean" and a raid could no longer endanger our work.

Then I went to the head of our illegal organisation, reported everything to him, and received strict instructions for how to conduct myself in the interrogation. It was my first police interrogation and my heart was about to burst. A detective read out passages from an anonymous letter claiming that "boxes filled with dynamite" had been carried out of my apartment. I told him that I had never worked in a munitions factory because I was scared of such stuff, and asked how I, a young girl, could possibly get hold of such dangerous things! I said the boxes contained apples, which had been sent to me, and I had sold a few boxes at a small profit. It did not occur to the officer that I, looking particularly skinny and miserable due to the wartime rations, could be involved in such exciting and dangerous things. He even showed me the anonymous letter with the accusation, but I did not recognise the handwriting.

Now I was able to reassure Arthur Schöttler and the small circle of comrades who knew about the weapons and understood the danger we were facing. Nothing had been betrayed. For the next few days, I remained completely isolated, so as not to give the police new leads in case they were watching me. Arthur and Fritz also avoided my apartment.

In the night of 8-9 November, I met comrade Fritz and was instructed to fetch comrade Schöttler between 4 and 5 a.m.; we were to hand out leaflets in front of the weapons and munitions factory in the Kaiserin-Augusta-Allee in Charlottenburg from 6 to 7 o'clock. After that, we were to prepare the weapons for distribution at a certain bar and then help out with the organisation of the demonstration at 9 a.m. When I roused Arthur Schöttler in the early morning of November 9, I woke him with the words: "Get up, Arthur, today is revolution!" He thought he was dreaming. Only when I shook him again did he open his eyes and say: "Gee, Cläre, is that you?" He jumped into his trousers, and after ten minutes we were out of the house.

As the morning shift began, we stood in front of the weapons factory and handed out our leaflets calling on the workers to put down their tools at nine o'clock. After we had completed our task around seven, we went to a bar in the Erasmusstraße. We were glad to warm up a little. There we quickly helped the other comrades unpack the revolvers and load the cartridges into the magazines. Suddenly we realised there were not enough cartridges left for Moabit. "Now what?" asked Arthur in dismay. "How is that possible?" "Well," I said, "that must have been botched on 1 November due to the rushed transport."

I knew the address of the munitions dealer. We absolutely had to go there to get more ammunition. Arthur and I each took a revolver and went to the wholesaler on the Kurfürstendamm. He was rather startled when we rang the doorbell "so early in the morning." We demanded 5,000 cartridges. He, of course, refused. Arthur Schöttler stood there in silence, clutching the pistol in his coat pocket. The gunrunner gave in to my urgent pleading and handed us 1,000 cartridges.

We left the apartment with a sigh of relief, and on the stairs we said to each other: "When these are all used up, either something will have been decided, or we will be dead." As we sat in the tram going back to Moabit, Arthur was filled with joy again, and he shook me and said: "Cläre, you saved Moabit." A woman sitting next to us thought we were a couple in love and said: "Well, it's not that warm today…" We looked at each other, laughing and thinking: Oh, if you only knew why we are so happy.

In Moabit, the comrades were happy when we returned safely bearing cartridges. The last magazines were filled quickly, and some more boxes of hand grenades were brought in. The first workers came out of the factories and took their weapons. Everything went its course, and the masses were calm and composed.

Finally, all the weapons had been handed out, and the demonstration began. First the armed men, then the unarmed ones, then the women. Arthur grabbed my hand to say goodbye, a firm grip and then: "So long, Cläre!" Then he marched at the front of the demonstration.

Our demonstration went along the Kaiserin-Augusta-Allee to the Schlossbrücke, without encountering resistance. We managed to disarm and occupy, without a single shot: the police station, the gas works, all the factories, the military hospital, the palace guard, the Charlottenburg City Hall, and the Technical University. Our demonstration had grown to thousands, and ended around noon at the Reichstag, where we met with other demonstrations.

I had long since lost sight of Arthur. Other comrades and friends ran into us. Joy, embraces, cheers from people who were meeting again after months of excitement, fear, and hard work. I was exhausted and sat down on the steps of the Reichstag until the crowd began to disperse, and went home in the darkness, dead tired but happy.

Translated by Nathaniel Flakin