"A green tongue to the sky's peaceful blue."

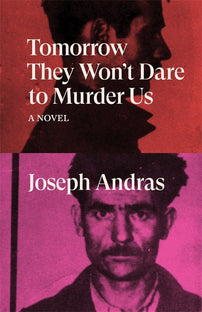

An excerpt from Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us: A Novel by Joseph Andras.

The River Marne sticks out a green tongue to the sky’s peaceful blue.

Clumps of trees unsettle an otherwise rigid horizon.

Fernand is in a short-sleeved shirt and his thin mustache has been freshly trimmed. Up above, the sun oscillates between two wrinkled, if ageless, clouds; down below the grass is speckled with poppies. There are hardly a thousand souls in this village of Annet. Fernand waves at an old fisherman and at someone who must be the fisherman’s grandson. The hospital doctor was right: he can feel that, too, he’s getting better. The air of the mother country is not without merit. Might he even, before too long, step onto a pitch again and play the soccer he loves so much? Be patient, be patient, said the aforementioned doctor, in a voice calmer than the Marne.

Fernand sings, something he goes in for whenever the walk or the mood demands it . . . The trees in the night lean in to listen to this sweet song of love . . . A tango. Carmen. The women of Clos-Salembier, his childhood neighborhood, always maintained that he had a nice wee voice, with a certain something in its timbre, a catchy roll, and that he should’ve tried his luck (they’d go on and on about it) in the cabarets or music-halls of Algiers. The birds say it again so tenderly . . .

It must also be acknowledged that the presence of pretty Hélène, whose first name is as lovely to the ear as her namesake, has played a part in his convalescence. She is from Poland, he gathers, overhearing a conversation she had with customers some two weeks ago. Her hair is thick and a distinctive shade of blonde, not unlike hay (slightly dark, matted and rough). Her eyebrows are thin, a pen line at the most; her chin is dimpled and she has prominent cheekbones, the likes of which he has never seen: two promontories above large cheeks. Every evening, or almost (a painful almost, since it marks her absence), Hélène helps her friend Clara, who runs the family pension where Fernand is staying, the Café Bleu. She makes appetizers and desserts. During the day, she works at a tannery not far from there, in Lagny—a village, she told him four days ago, that was virtually destroyed during the Great War. The first time Fernand saw her, she was serving wine to a couple seated a few meters away from him. Hélène appeared edgewise, her perfect profile projected on the wall behind her, that shadow slightly swollen, in the middle, by her nose. He noticed her smile, and that cheek—he saw only one at first, obviously—a Mongol’s cheek (Fernand has never met any Mongols, but that at least is the image in his mind). And then those eyes: their far-flung blue, journey and meridians for the North African kid he is. Two little tablets, pointed and cold, colored the kind of wolf-dog blue which rummages around your heart, never asking for permission or wiping its feet on the doormat—for this blue would not fail to make a doormat out of you, one day, if it could ever come to blame or love you. He had used indecision as an excuse, at a meal last week (the choice was caramel-cider tartlet or strawberry crème brûlée), to incite their first exchange. She was partial to caramel and asked him where his accent was from: from Algeria, ma’am, it’s my first time in France, well, yes, they say Algeria’s in France, sure, but still it’s not the same, you have to admit that it’s . . .

She is here tonight.

Fernand sits down and orders the set meal. Her eyes are little frosted pearls, she smiles and goes off with his order, explicit creases at the back of her skirt, ankles as slender as her wrists . . . Hélène was born in Dolany, a village somewhere in the middle of Poland. Her parents named her Ksiazek at birth, and the family, the three of them and her brother, migrated to France when she was eight months old. For work. They were agricultural laborers. Her father is called Joseph—like the Judean carpenter or the Little Father of the Peoples, the choice is yours—and her mother Sophie. He plays violin and she comes from a wealthy family. She let her class down to escape with the man she chose to love . . . too few hearts are ready to break ranks. They settled in Annet, with chickens, rabbits, four pigs and a few pigeons.

But Fernand does not know any of this yet: he learns it in her car a few days later, when she takes him to the hospital in Lagny for his lung X-ray (he pretended not to know where to go and asked for her help, innocently, this evening, since she is from around here . . .). She has no memories of her native country, Hélène explains while driving her car, and only knows what her parents have told her about it. Her father lives there now, a very unfortunate affair: he only meant to go for a brief stay, but the Polish People’s Republic never allowed him to get a return ticket. His letters exude all of his bitterness. Fernand does not hide the fact that he votes with and for his own, the workers. And while he may not have read Marx like the Party leaders, each and every page of Capital and the thousands of notes at the bottom of each, he has no doubt that it will necessarily happen, one day, the sooner the better: do away with all of that, fat cats, landowners, milords, money-men, scoundrels—those that own the means of production, as those leaders like to say. She laughs: why not? Communism would be nice, sure, provided that it’s actually implemented, equality for all, the real thing, without bigwigs or bureaucrats, without propaganda or political commissars. But that doesn’t really exist anywhere, not even in the USSR, she points out. Fernand won’t attempt to deny it: and besides, how could he? His every answer takes the form of a slightly foolish smile. It’s right here, we’re almost there, she says, pointing to the hospital. She parks and Fernand, at the window, tells her he’ll be quick, promise, you can wait for me at the café over there. He takes a bill out of his jacket pocket so she can pay for a beverage, but she refuses, it’s useless to insist.

A tough one, this Hélène, thinks Fernand while climbing the steps. A hell of a woman.

***

Joseph Andras is the author of the novels De nos frères blessés and Kanaky. Awarded the Prix Goncourt for De nos frères blessés (Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us), he refused the prize, explaining his belief that “competition and rivalry were foreign to writing and creation.”

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]