Chi Chang: A Chinese American Volunteer in the Spanish Civil War

Chi Chang, a Chinese emigrant to the United States who joined the Communist Party and volunteered for the International Brigades to fight fascism during the Spanish Civil War. His story is retold here by Hwei-Ru Tsou and Len Tsou, and translated into English from the original Chinese by Agnes Khoo.

More than 80 years ago, Chi Chang, a US-trained mining engineer, left New York for Spain to join the International Brigades to fight fascism. His story was almost forgotten, until the publication of a Chinese-language book The Call of the Olive Laurel: The Chinese Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) (Taiwan, 2001) and its Spanish edition (Madrid, 2013).

Chang left for the US from China after completing high school and earned a BSc. degree from the University of Minnesota in 1923. Racism and the Wall Street crash of 1929 awoke his political consciousness and changed his life. The following piece tells his story of fighting fascism in Spain. This is an excerpt from the 2015 edition of the book in Chinese. To uncover this hidden history, the US-based authors traveled extensively across Europe and China, visiting archives and interviewing veterans who had fought together with the Chinese volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. The English translation is provided by Agnes Khoo.

* * * * *

June 1937, the scorching sun was baking the earth like a steamer. Chi Chang expertly maneuvered the steering wheel of a giant truck, his arms looking sunbaked. His shirt collar opened to reveal ravines of sweat, like earthworms slithering down his torso, tickling and itching him as he drove. He was speeding from Valencia towards the inland. The day was getting hotter. He took out a wrinkled handkerchief to wipe sweat from his forehead to stop it from getting into his eyes behind his glasses. He glanced at the rear mirror to check on the cargo in his truck. He frowned. He was already sun-burnt from the inside-out, and the boxes of unrefrigerated fresh meat in his truck would certainly go bad before arriving at Albacete, which was still another two to three hours’ drive ahead. He stepped harder on the accelerator, hastening the truck towards the southwest, like an angry beast.

The roads bent and curled around the hills as the truck climbed over the undulating terrain. Just as he thought he had reached the end of the road, which almost touched the sky, another stretch of hills came upon him. The road climbed endlessly and snaked sharply up the steep slopes; once again, it looked like it could almost touch the sky at every bend. As his truck meandered through the rolling hills, he caught a glimpse, through the thick growth of olive trees, of a donkey cart and a peasant in a dark jacket, ambling along leisurely right in the middle of a sharp turn. Chang frantically hit his horn, but neither the donkey nor its owner took notice. The truck came to a sudden halt in the nick of time, as Chang halted perilously close to the back of the little two-wheeled donkey cart. He was furious. Chang was just about to swear when the peasant recognized him as a member of the International Brigades. The old man’s wrinkled and sunbaked face broke into a smile. He saluted Chang with his right fist, “Salud, camrada!” The only swearing Chang could summon up at that moment, was to raise his own right fist.

Life can be so unpredictable; a year ago, Chi Chang could not have imagined himself in Spain when he was all alone, worried and concerned about the war in China. Since the Japanese occupation of three northeast provinces in China on 18 September 1931, the war in China had escalated. The Japanese army had crossed the Great Wall and was heading straight for Peking, into Shanghai. Yet, instead of fighting the Japanese, Chiang Kai-shek felt more threatened by, and was determined to eliminate, the communists. As reported by the American press, it took the kidnap of Chiang Kai-shek by his General Xueliang Zhang at the end of 1936, to force Chiang to ally with the communists against the Japanese invasion.

July of the same year, Spain descended into a civil war. General Francisco Franco and his generals had staged a coup, supported by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, who supplied Franco with arms, airplanes, and troops. Their aim was to overthrow the new, socialist-leaning and democratically elected government of the Spanish Republic. Western governments had refused to intervene and stayed on the sidelines as the war raged on, allowing the fascists to destroy the Spanish government. This colossal injustice had touched the conscience of the world. People from all over the world volunteered to join the International Brigades in aid of the Spanish Republic, which was by then on the verge of annihilation. Chi Chang was one of the volunteers.

On 27 March 1937, Chang boarded the S.S. Paris, the passenger ship from New York for Paris. With him were the Thortons, a father and son from California. There were altogether sixteen of them en route to Spain. The father was forty-three years old, a former miner turned salesman. His son was twenty-two and a sailor. Father and son looked more like brothers. They used to organize the unemployed and homeless in California and led anti-hunger protests. They not only wanted to feed the hungry but also to destroy the unjust and inhumane system of capitalism.

Their lofty and courageous aspiration extended far beyond America, and they wanted to embrace the world through their activism. They thought of those who suffered as their brothers and sisters. Solidarity transcended all national boundaries. Even though their passports were stamped with, “Not Valid for Travel to Spain,” nothing could stop them from going there to fight “the good fight.” During the journey, the group was careful not to disclose their destination except to those closest to them. No one could have guessed that Chang, this tall and slender man of the East, who looked so gentle and urbane with his spectacles, could be heading for Spain!

After staying for three to four days in Paris, the men travelled southward by taxi towards the Pyrenees mountains. On the way, Chang watched the majestic mountain range towering across the sky. He felt cool and lightheaded, somewhat overcome by a sense of doubt. He asked himself, am I capable of crossing these mountains? He was by then, a middle-aged man of thirty-seven. He quickly told himself that age had nothing to do with it. There were others older than him in the group, but they were strong and physically fit. Despite his height, Chang was sickly. He was worried about falling ill halfway through the mountainous trek. He was told that many men in their thirties had failed and were forced to turn back. But he had travelled thousands of miles from the United States, and he was adamant that he would not be easily dissuaded.

As night descended upon the Pyrenees, the group began to cross over to Spain. The men held onto a rope, walking behind one another in a single file, and trailed cautiously behind their Spanish team leader. They were crossing one mountain range after another in total silence. The night was so dark that they could hardly see in front of them, but it also shielded them from the French border police.

That one single rope, which everyone held onto for dear life, was their only compass leading them towards their destination. But they could not tell how wide or narrow the mountain path was. They had to walk as close as possible against the mountain wall so as not to fall, keeping pace with the person before them. The sound of broken stones under their feet, falling off into the dark abyss of the deep valley as they hit the ground, echoed chillingly in the cool night air. Chang had to convince himself again and again that he would see the other side of the mountains. It was a test of will; the toughest and harshest test of his life. He was determined to overcome what felt like an endless feat of mountains after mountains until he finally set foot on the Spanish soil.

His group finally arrived at the Headquarters of the International Brigades in Albacete on 14 April. His conquer of the Pyrenees mountains came with a price, his sciatica had flared up again and he had come down with a flu. High fever and a persistent cough tortured him for three weeks. He became very weak before his condition finally stabilized. Due to his poor health, he was barred from the battlefront and was assigned to the Transport and Logistics unit as a truck driver.

Once, on his way to Madrid, his truck had broken down in a quiet residential area. He got out of the truck, opened the bonnet and stuck his head inside to inspect the motor. Soon enough, the faces of two cute little boys appeared under the bonnet. They were about twelve or thirteen years old. The boys fired a volley of questions at him while pointing at his truck. He understood, but his Spanish was too rudimentary to compose an answer.

Stuttering and with great effort, a few Spanish words stumbled out of his mouth, almost at random. His hands gestured vigorously to accentuate his meanings. The kids seemed to understand what he was getting at and they laughed together. Then, a loud explosion nearby startled him.

He asked the boys, “Aren’t you afraid?” One of the boys answered bravely, “No.” The other boy explained, “Those shells will not drop over this way today.” And he continued, “Tu Chino?” Chi Chang nodded. The boy responded, “Chicos en China bombardeados tambien! Fascistas, no bueno, todo del mundo.” Looking at their childish faces, Chang could not agree more with their sharp, political critique. He thought to himself, “Why are adults twisted and confused about what is good or bad in the world, and not these children?”

Chang’s supervisor in the International Brigades was impressed by him; he was hardworking and very helpful towards his comrades. However, he was “sickly,” so before long, Chang was transferred to office work in the 15th Brigade. His first technical assignment was to design a concrete building. Chang was always busy, waking up at five every morning and working late into the night. He had wanted to write but soon gave up. He even had to steal time from work to write a letter, let alone embarking on a writing project! Nonetheless, he did manage to complete a short English essay, which analyzed the war against Japanese aggression in China entitled “Far East Possibilities,” with a Spanish translation.

On the 5th of June 1937, he wrote a long letter from Albacete to The Chinese Vanguard, a newspaper in New York, describing his experience in Spain. He mentioned that there were at least three other Chinese in the International Brigades: “Two of them were injured and convalescing in a nearby hospital but I have yet to meet them. I have however, met a Mr. Yen who worked in the office.” Mr. Yen was in the army of Zuolin Zhang. Yen left for France in 1916 and joined the International Brigades in 1936. He was injured in the battlefield. Chi Chang and he would talk for more than three hours a day. He got to know from Yen that there were Chinese fighting in the Spanish Civil war at various frontlines.

Later, Chang heard that another Chinese, by the name of Dong Hong Yick, had joined the Brigades. Yick used to wait at tables in a Chinese restaurant in New York’s Chinatown and he was assigned to the Infantry of the 15th Brigade. When the 15th Brigade passed through Albacete, Chang asked about Yick and was told that he had been wounded in a battle in Belchite; his right big toe was blown open by a dumdum bullet and he was sent to the Benicàssim hospital for treatment. Chang was still taking in the grim news when a big, blond, bearded and burly man suddenly rushed up and held his hands tightly. Chang was taken aback at first before he recognized him. It was Waino, the bartender from the bar Chang used to frequent in Minnesota!

“By God, I am glad to see you! Heard that you are around. Still drinking much?” Excitedly, Waino fired a dozen of questions at Chang. “What are you doing now? What’s the matter with truck driving? Why don’t you join my brigade so we can be together?” Then dropping his voice to a solemn and conspiratorial tone, he said, “Didn’t you know that I came in on the City of Barcelona, the boat that was sunk by an Italian submarine?” There were more than sixty Americans on board and more than two hundred people of other nationalities. Waino was lucky to grab hold of a life saver. While floating at sea, he saw people scattered all over the ocean, appearing above the waves only to disappear again as the waves surged and retreated in turns.

“I was shivering like a leaf, but those communists! You know what they did?” Waino exclaimed incredulously, “They started singing the 'Internationale' in nearly every cock-eyed language you ever heard.” Waino did not know the song at first, but said it had made him very emotional. Warmth and strength had surged through his body as the strong and sturdy voices bellowed in such gusto, daring death. He felt invigorated and forgot the danger he was in and became brave and strong too. He had learnt the song by heart. “I am going to be a communist when I get back to America, damned right.”

* * * * *

Chi Chang’s arrival at Spain was a response to the call of the Communist Party of the United States of America to fight the fascists in Spain in 1936. Since he was single without the burden of family and responsibility, he had gladly signed up.

When he arrived in Spain in April 1937, Chang wrote in his registration form,

My original intention was to find a place where my technical training and experience would be of value in this struggle, but I had no objection to be with the International Brigade, provided that I can make some concrete contributions toward the final victory of the Spanish Government.

That was how he became a Brigadista. He was first assigned to the Transportation and Logistics Team but due to his illness, he was soon transferred to office work in the 15th Brigade where he could make use of his engineering expertise. His duty was in construction and architecture. He also taught the soldiers surveying at the Officers’ Training School.

During that time, a songbook, “Canciones de Guerra de las Brigadas Internacionales” became very popular in Spain. These were revolutionary songs from Spain, Italy, France, the Soviet Union, and Germany. Chang had autographed the song book of American Brigadista, Harry Fisher. He signed his name in English on the cover as“Chi Chang, Changsha, China.” He also signed his name in the song book of English Brigadista Sam Walters as, “Chi Chang, China, C.P.U.S.A.,” clearly indicating himself as a member of the American Communist Party.

One day, Chang met his fellow alumnus from the University of Minnesota, George Zlatovski, in Almana city near Albacete. George had also joined the International Brigades, and was driving a truck on his way to Alicante to procure asbestos tubes. He was thrilled to meet Chi Chang. He embraced Chang forcefully. The two men talked through the night. They recalled that shortly before they both left for Spain, they had been performing a play in Minnesota! It was a famous play about workers’ strikes, “Waiting for Lefty” by Clifford Odets, which Odets had written in three days in 1935. Chang was in charge of the props. Once, when the lead actress and the actor who played the taxi driver were dancing together, the music did not play. Chang had forgotten to tune the gramophone in time! Fortunately, the actress’s wit saved the day. She sang impromptu and elegantly finished the waltz with her partner. The two men broke into laughter as they recalled the incident. George teased Chang that he should never forget to load the cannonball into the cannon at the war front!

* * * * *

Chi Chang was sickly. In the Medical Committee Report of 17 July 1937, Chang was diagnosed of sciatica. In the Graduate list of the Tarazona Officers’ Training School, dated 9 February 1938, it was recorded that he was too weak for the frontline. His pre-existing condition of chronic rheumatism had also flared up in Spain, which forced him to rest. On 9 March 1938, he was admitted to the Pasionaria Hospital in Murcia. Coincidentally, another Chinese Brigadista from Switzerland by the name of Ching Siu Ling was also admitted there. They quickly became close friends. Ling’s contact person in Paris was Jiansheng Zhao who often asked about Chi Chang in his letters.

In Zhao’s letter of 10 March 1938 to Ling, he wrote,

You must have met our two Chinese comrades whom we sent to Spain from the US by now? The comrade by the name of Chi Chang is a mining engineer. He had written to us a few times from Spain. Please pass our salutation to them when you meet.

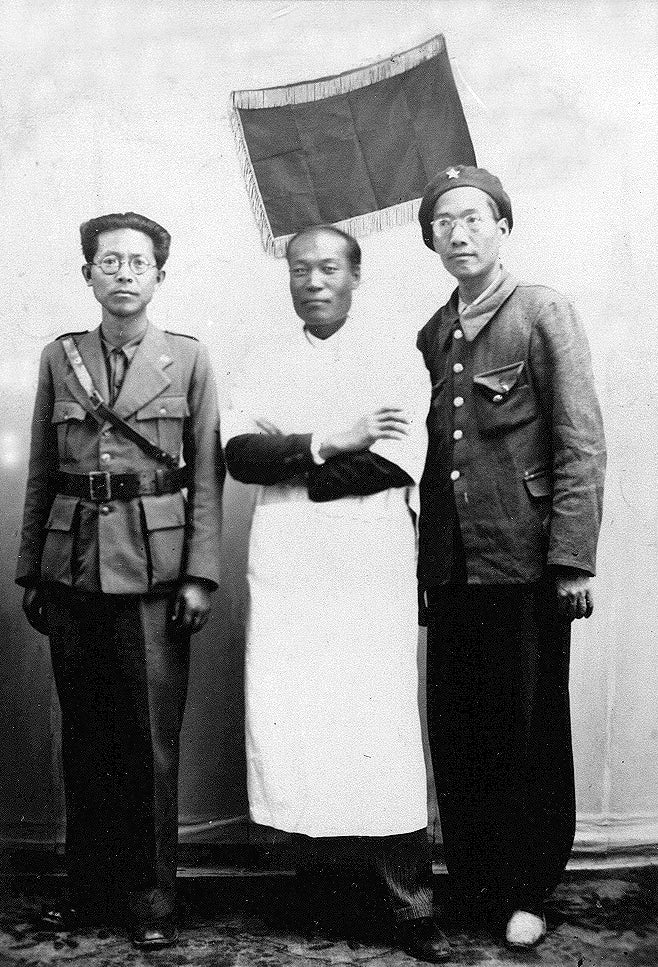

Since Chang and Ling had ended up in the same hospital, they got to spend a lot of time together. In Ling’s letters to Zhao, he mentioned Chang’s current situation. The International Brigades magazine “The Volunteers” published a photograph of the three Chinese men at the hospital: Ling, Chang, and Hua Feng Liu. As summer approached, Chang was transferred to Orihuela for convalescence, twenty-five kilometers north-east of Murcia.

In the hospital of Orihuela, there were a few American Brigadistas recovering from their injuries. Chi Chang was the only Chinese. His features had caught the attention of American Brigadista, Curley Mende. Mende was surprised at Chang’s fluency in English, which he spoke without an accent. One would think he was a born-and-bred American. “But I did not know which state he was from. In those days, we did not ask personal questions.”

Mende had the impression that all Chinese were small, but Chang was tall and slender, like a long and delicate bamboo cane. Sitting beside the strong and burly Mende, they were a picturesque pair, like the Arabic number 10. Mende also recalled that Chang loved to wear the Basque beret and, “no matter how warm or cold, he always had his coat on, all buttoned up to the neck.” Mende did not think it was appropriate to ask Chang about his illness, but the Belgian nurse told him that Chang had tuberculosis.

Being confined to the hospital, these patients had a lot of time in their hands. They gathered to chat. Mende remembered Chang as serious, gentle, and polite, a man who never raised his voice, in complete contrast to Mende who was loud and boisterous. Mende was direct and honest, never hesitant to speak his mind. He would joke like a teenager, but remembered “We did not talk about women, only about politics. Chi Chang told me he was going to leave Spain for the US soon and from there, he planned to return to China.”

Hwei-Ru Tsou and Len Tsou, each with a Ph.D. in Chemistry, worked in sciences in the United States. They dedicated their after-work hours to search for Chinese and other Asian volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. They can be reached at: LYTHRN@aol.com

Besides translation work, Agnes Khoo lectures on International Relations and writes on Asia-Africa Relations from Ghana, West Africa.