Berta Cáceres, Rebel with a Cause

Berta was eighteen years old and still weak from giving birth when she joined the war effort with the National Resistance, part of the guerrilla offensive against the Contras in El Salvador.

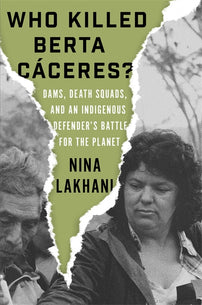

An excerpt from Who Killed Berta Cáceres? Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet by Nina Lakhani.

By 1983, the twelve-year-old Berta was rebellious and outspoken, according to Ivy Luz Orellana who met her on their first day in 7th grade. ‘She was very studious, learned quickly and was a natural leader who hated following pointless rules and would speak out against unfairness,’ said Ivy, who shared with me a splendid collection of school photos that show a youthfully frivolous side of Berta. In one, Berta is fifteen and strutting along some sort of pageant catwalk wearing a fancy white dress, make-up and kitten heels, beaming happily. The picture appeared in the local paper.

By then she’d met her future husband, Salvador Zúñiga, a student activist six years older who was regularly invited by Doña Austra to the family home. Zúñiga had co-founded the radical Patriotic Student Organization of Lempira (Organización Patriótica Estudiantil de Lempira – OPEL), whose main objective was to purge Honduras of foreign armies. This made Salvador a target, and in 1984 rumours circulated that he was on a military hit list. With friends and colleagues already dead or disappeared, the nineteen-year-old crossed the border into El Salvador where he helped move the sick and injured to relative safety in Honduras.

After middle school, Berta, like most of her siblings, trained as a primary school teacher at the La Esperanza normal, mainly because it was the only free secondary education available. She started the three-year training course in 1986, aged fifteen, and immediately joined OPEL. When the radical student group’s president was killed, Berta was elected to succeed him. In one of her first acts as president, she organized strikes to protest the unfair exclusion of a student, which saved him and got the teacher behind it thrown out. ‘By the time we entered the normal, Berta’s ideals were very clear: she was a leader and wanted to be free, do other things, rather than get married and have kids,’ said her old schoolfriend Ivy.

This didn’t stop Berta having fun, and her friends remember her as witty, outgoing and happy to break the rules. Ivy recalls that ‘Berta was beautiful and had lots of boyfriends . . . She loved to dance, we were great dancers, but our mothers were strict so we’d sneak off to the Paraíso disco in the afternoons. We danced to merengue and 80s American pop music like Michael Jackson, songs in English we didn’t even understand.'

'Berta was popular, happy and loved life, and that never changed in the thirty-plus years we were friends, even when things got so difficult at the end.’ In later years, Berta would jokingly call old schoolmates, like Ivy, who became National Party voters, capitalistas de mierda (fucking capitalists). She never lost her playfulness, nor avoided people with opposing views.

Outside the normal, Berta got serious with like-minded new friends. Like her brother Carlos and his friends a decade earlier, the youngsters met in secret to read banned books on the Cuban revolution and Marxism, debating revolutionary ideas and real-world tactics to help comrades at home and in neighbouring countries. It was a dangerous time to be a revolutionary, and Berta kept this world from her school chums, who had no idea that she started dating Salvador Zúñiga in 1988, the last year of teacher training. She was seventeen, he was twenty-three, and by this time fully enmeshed in the Salvadoran war effort, supporting units across the tiny country with information analysis, logistics, intelligence and counter-intelligence gathering.

Berta couldn’t get enough of his stories, and was impatient to be involved. ‘Every time I came home I brought her revolutionary texts which we discussed, but we also exchanged poems and romantic novels. She wanted to come with me to El Salvador, that was the plan, that we’d go together after she graduated from the normal then she got pregnant.’ Zúñiga planned to return to El Salvador for the last rebel offensive, but tried to dissuade Berta from coming with him. ‘War isn’t romantic, it’s cruel, and I didn’t want Berta to come, but she was insistent.’ Doña Austra, who knew nothing about her youngest daughter’s war ambitions, was at the same time trying to ship Berta overseas to have the baby, in order to avoid a town scandal. Berta refused, and the young lovers plotted behind her back.

Olivia Marcela Zúñiga Cáceres was born on 28 June 1989. She looked just like her mother. Three weeks later Berta said goodbye to Austra, telling her that she was taking baby Olivia to visit her brother Carlos in Canada. Instead the young parents left the newborn with Zúñiga’s sister, who lived in nearby Siguatepeque, and went to join the guerrillas. It would be several months before they held Olivia again. The time Berta spent in El Salvador shaped the rest of her life.

Berta was eighteen years old and still weak from giving birth when she joined the war effort with the National Resistance – one of four guerrilla groups in the coalition that formed the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Here, her nom de guerre was Laura or Laurita. Life on the front line was tough. The unit was constantly on the move, and the incursions were rugged and dangerous. The young militants were assigned to logistics and reconnaissance missions – mostly supportive, non-combatant roles. They monitored the radio and put together communiqués for the leadership on what the State Department, Pentagon, European governments, BBC and international groups like Amnesty International were opining about the conflict now in its tenth year. Sometimes they went on separate missions to different parts of the country.

‘From the very first sortie, she was intrepid and determined, even going ahead with the exploration unit without me. Berta never cried, she was calm, strong and fearless even when our unit came under attack. She ate and slept when she could, but showed great discipline even though she hadn’t been trained,’ Salvador said.

Vidalina Morales, a local guerrilla, remembered that Berta seemed shy in Salvador’s presence, and that he at times ridiculed her in front of comrades. But she never shied away from any physical or psychological challenge, and positively bristled if anyone suggested taking it easy.

Antonio Montes, nom de guerre Chico, was a twenty-nine- year-old combatant when Berta and Salvador joined his unit on the imposing Guazapa Mountain in Suchitoto, from where the guerrillas launched the last offensive on the capital San Salvador in November 1989. Berta was part of the health brigade, drawing on her childhood experiences with her mother to help treat wounded combatants as they advanced towards the capital. Back at camp after the nine-day offensive, Berta organized classes for the children and taught literacy to adults in the guerrilla-controlled areas, which tried to retain a sense of normality despite being under constant threat of attack. Her commitment to the Salvadoran cause impressed Chico.

‘Berta witnessed terrible atrocities, she saw the consequences of war on unarmed civilians and was visibly moved by the suffering. But she was a restless young woman, with a hardworking spirit and willingness to contribute to all sorts of activities with people trying keep their lives going in complex conflict zones. It’s clear that these experiences marked the rest of her life.’

In late 1989, as Berta and Salvador prepared for the final offensive, a disarmament deal to end the Contra War in Nicaragua was signed in Honduras. The Tela Accord essentially marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War.

That same year, the once feared general Gustavo Álvarez was killed, prompting Carlos, Berta’s big brother, to return home after more than a decade abroad.20 In 1989, a few days after Álvarez was killed, human rights defender and physician Dr Juan Almendarez was in Bolivia at an anti-tobacco conference when he got word that his name was circulating on a military hit list. After Ambassador Negroponte had him sacked as university rector in 1982, Dr Almendarez had frequently been followed, photographed and harassed, so it came as no surprise. Before boarding the flight home, he told a friend: ‘If I don’t make it home, tell the world it was the military.’ This probably saved his life. Arriving in Honduras, Dr Almendarez was held at gunpoint in an airport taxi by agents from the Argentine Anti-communist Alliance (AAA), School of the Americas graduates operating in cells across Central America. He was taken to the DNI’s infamous torture centre in Tegucigalpa for interrogation. ‘The main interroga- tor knew every move I’d made for years, and named several compañeros who’d been disappeared and murdered …“How shall we kill you?” he asked me. “Peel your skin off, cut you in pieces, use a big hammer, or electric shocks, which would you prefer?”’ Another interrogator demanded to know who killed General Álvarez. ‘I told him that it was probably the CIA, which is what I believed.’

Berta and Salvador returned in February 1990. Berta, almost nineteen, was pregnant with their second child and happy to be reunited with baby Olivia. But the couple remained committed to the cause and would secretly go in and out of the country with high-ranking fighters like Commander Fermán Cienfuegos, whom they escorted between Nicaragua and El Salvador, often via Doña Austra’s safe house.

Bertita Isabel Zúñiga Cáceres was delivered at home in La Esperanza by her grandmother on 24 September 1990. But even then, the couple didn’t end their militancy. They went back several times, sometimes with both infants who served as the perfect camouflage to smuggle Salvadoran fighters across the border. Once, when Olivia was eighteen months old and just learning to talk, she called out ‘Pompa, pompa!’ to the soldiers on the border, confusing them with friendly guerrillas on the other side whom she knew as compas (short for compañeros).

Enough Bloodshed

In El Salvador, 80,000 people died, 1 million were displaced and 8,000 disappeared over twelve years of brutal conflict. In Guatemala, more than 200,000 mostly poor indigenous campesinos were killed in the thirty-six-year war, 93 per cent of them by US-backed forces. The decade-long Contra war in Nicaragua cost 50,000 lives. But no matter how many US tax dollars were funnelled to military dictatorship after military dictatorship, no matter how many weapons and planes America sent, there wasn’t a single battlefield victory. Every peace deal, however flawed, was signed thanks to dialogue and negotiations off the battlefield, almost certainly greased by economic interests. Berta and Salvador came home certain of one thing: armed struggle was not the way forward. ‘We saw with our own eyes how war generates abuses on each side, and that the majority who died were young, poor men and women who took up arms because they were hungry or forcibly recruited, not because of ideology,’ said Salvador. ‘Times were changing, and we came home convinced of the need to launch an unarmed social movement. Whatever we did in Honduras, it would be without guns.’