Manual of War: on Bertolt Brecht’s War Primer

Brecht considered War Primer part of “a satisfactory literary report on my years in exile,” as he wrote in a 1944 journal entry. Since this first English language reception of War Primer on the centenary of Brecht’s birth in 1998, what are we now to make of his poignant modernist epic of four-liner lyrics and scrapbook photos? Today, in our post-crash era, with its renewal of Marxism, Brecht the formalist can be freed from a series of postmodern qualifications. War Primer’s historical intervention can be seen in a new way today. With the far right politically relevant again, Brecht’s image-by-image analysis of social democracy, America, and fascism, which is the veritable heart of War Primer, possesses fresh relevance.

War Primer is 40% off, along with all our related Brecht reading, until Sunday June 11 (midnight UTC). Click here to activate your discount.

Epigrams for the Age of Reproducible Images

When War Primer (Kriegsfibel) first appeared in English nearly two decades ago, its Second World War-era photo-epigrams (fotoepigramme, as Brecht dubbed them) would take readers into a core sample of the twentieth century’s unparalleled violence. A compelling use of the epigram alongside newspaper war photography, War Primer’s image-poems each dialectically exemplify a moment of conflict during the war. Chiseled rhyming quatrains, a form borrowed from Kipling and rendered expertly by translator and scholar John Willet, separate an epic of World War II into instances, some familiar. Others confound expected patterns. The book is a verbal-visual montage of irony, discord, and hope. Like a child’s primer on letters, animals, or, from our perspective, political dinosaurs, it presents a veritable alphabet of figures, from individuals like Hitler, Goebbels, and Churchill, to crowds of refugees, soldiers, and anonymous elements of the masses caught in the fighting. Estranging the interstate conflict, Brecht here depicts soldiers, peasants, families, workers, and others — the protagonists of his historical materialism — in an underlying class struggle made obscure by fascism, Stalinism, and the World War.

Brecht considered War Primer part of “a satisfactory literary report on my years in exile,” as he wrote in a 1944 journal entry. Since this first English language reception of War Primer on the centenary of Brecht’s birth in 1998, what are we now to make of his poignant modernist epic of four-liner lyrics and scrapbook photos? Today, in our post-crash era, with its renewal of Marxism, Brecht the formalist can be freed from a series of postmodern qualifications. War Primer’s historical intervention can be seen in a new way today. With the far right politically relevant again, Brecht’s image-by-image analysis of social democracy, America, and fascism, which is the veritable heart of War Primer, possesses fresh relevance.

Writing in the 1990s, playwright David Edgar could maintain that while the “sly, cool, back-footed manner” of Brecht remained current and even humorous, his Marxism was “old-fashioned, out-of-place, even risible.” Not so today. War Primer makes use of lyrical and prosaic forms, the latter being a collective, collaborative enterprise with mass periodicals. Its image-poems relate a kind of dialectical Marxism. Relying on ready-at-hand epigram and reproducible image, coupled with their variety of speakers, the image-poems offer miniatures of his innovative repertoire — separation of the elements (Trennung der Elemente), montage, social gesture, and estrangement effects (Verfremdungseffekte). War Primer is neither mere scrapbook nor a John Heartfield-inspired assemblage, but a book that rewards a reader submerged in the current times of aggressive imperialism fuelling waves of blowback. It resounds with Brecht’s earthy bluntness: “God is a fascist.” In War Primer the instructive dramatist puts his geopolitical Marxist lessons on tersest display.

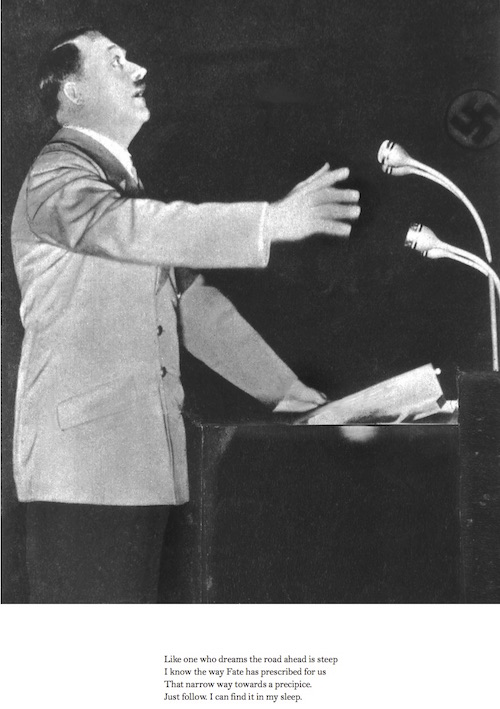

As Willet’s afterword notes, the production and publication of the text were certainly complex. While War Primer proceeds chronologically — with early images of an ascendant Hitler speaking on the rostrum and the conquest of Republican Barcelona by Franco’s army, followed by a long passage devoted to the terrible reality of aerial bombardment during the various phases of the Blitz — the composition of the text was sporadic until several years into Brecht’s life in California. Steady access to Life magazine gave him more suitable material for epigrammatic study. Brecht: “The truth regarding the prevailing conditions in the world has profited little from the frightening development of photo-journalism: photography has become a terrible weapon against the truth in the hands of the bourgeoisie.” In War Primer, the epigrams serve as corrections, as comments and captions that should have been appended beneath the image in the first place. The anger and sympathy in the lines arises in response to the damaging blows inflicted on the interwar left.

Historical context is paramount when reading them. The photo-epigrams work through the Comintern’s zigzags of political positions in its Third Period, which began on the ultra-left by breaking decisively with the social democrats, now dubbed social fascists. This 1928 line was exchanged for the Popular Front era’s collaboration with both social democrats and national bourgeois forces; things would change again in the era of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, as any Soviet hopes for a triple alliance with France and Great Britain collapsed. The Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union would scramble the Comintern’s line once again. And now for a first maneuver into Brecht’s album-like depictions of the dramatis personae of mechanized warfare.

Critique of Total War

War Primer’s portrayal of the war years remains a fresh one. Even recognizable images and persons are rendered unfamiliar in high literary language derived from August Oehler’s German translations of Greek epigrams. Hitler fills the opening image. The quatrain, that compressed verbal machine for quickly producing a cumulative force, treats the cunning and catastrophe of his rise:

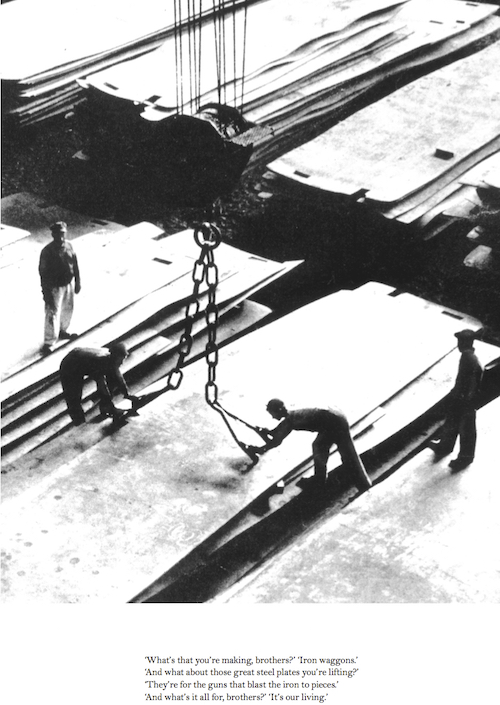

The image, mediated by the poem, offers a vision of archaic rather than revolutionary modernity, which Nazi power aimed for. But the lessons in this primer are multifaceted, as the second photo-epigram shows with its image of the war economy. Photography and lyric poem upset and challenge one another. An exchange among comradely workers is separated out from Hitler’s voice:

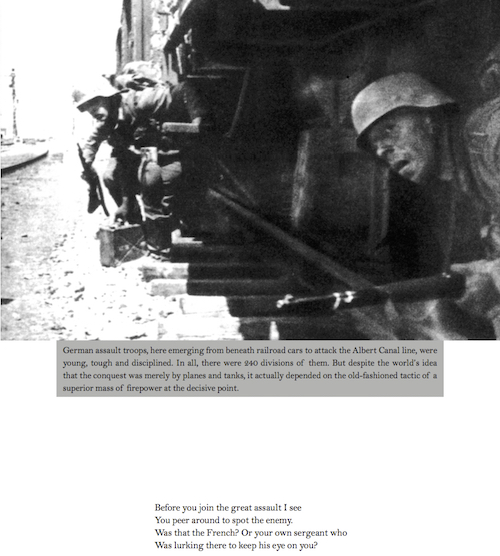

The war is binding men together in working conditions, while also forcing them into mutual destruction, as in the eighth epigram, where a German soldier faces not only a French enemy but also a sergeant behind him with violent means to compel his loyalty:

The photo-epigram catches the exhausted and fearful soldier in a moment of spiritually meaningful hesitation. A feeling of inner revulsion ever so briefly flickers forth on his blurred face.

From ground conflict (“Unblock the streets to clear the invaders way”) and maritime tragedy (“Fisherman, when fish have filled your net / Remember us, and let just one swim free”) the photo-epigrams turn to the Blitz. Liverpool speaks for its harbor glimpsed from above:

Photo-epigram 20 depicts one of the many cockpit men bent on urban annihilation. The airman pumps his fist in the air, only to be profoundly undercut in the ensuing quatrain:

The above epitomizes the major imperatives of the form in War Primer: to clarify directly the image of “splendid” war making and derring-do; to specify weaponry in the tradition of ancient epigrammatic poetry. The Blitz passage gives on to a spiral of sinister Nazi and German politicians, those really responsible for the disaster of aerial bombardment in pursuit of imperial conquest. Hitler graces a dinner table in a candid shot:

The appetitive character of the photo is here amplified by the epigram in Hitler’s voice. But behind Hitler stands the catastrophe of the German Social Democrats (SPD), whose leader Friedrich Ebert, Weimar-era German President, features as the veritable face of craven opportunism.

The configuration of German officials includes information “doctor” Goebbels in close-up (“Even my club foot seems a fake today”) and, much later, Gustav Noske, interior minister of the SPD-led government who directed the repression of the Spartacist revolt in 1919. Here Brecht is close to the Comintern’s Third Period ultra-left line, which held that Social Democrats were the left wing of fascism. As a practical consequence, cooperation between the Communists (KPD) and SPD would break down with disastrous consequences, as the SPD leadership also refused to cooperate with the KPD. This trenchant criticism of SPD officials kept War Primer from the printers in post-war East Germany for a half-decade, as many former SPD officials were integrated into the Socialist Unity Party (SED) government.

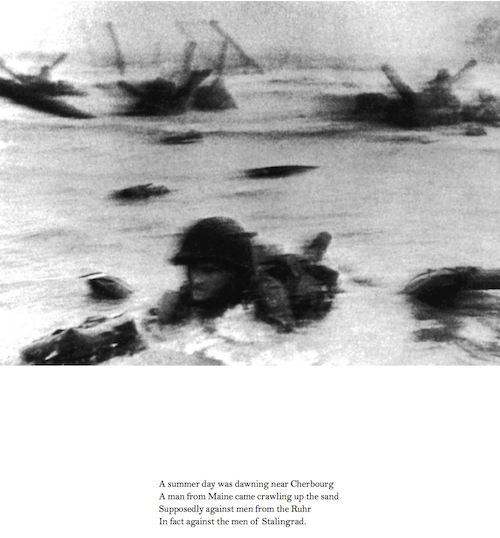

No Popular Front-era line of the Comintern overtly materializes in the text. Instead of a Lincoln Brigade, America has sent a late and cynically deployed force into Europe on D-Day after the Germans have sufficiently weakened the Soviets:

Far from the usual depictions of America’s invasion of Normandy, Brecht emphasizes the scheming and briefly submerged anti-Communism of America’s foreign policy. In the war’s Pacific theatre, American troops figure in a series of images (including 55 and 61), but most salient here is the sympathy of an ordinary GI for a Japanese child. This photo-epigram transmits the theme of a hauntingly distant peaceful future familiar to readers of Svendborg Poems.

Conceived in the main while in California exile, Brecht, the wry observer of America (“It’s Hollywood v. Hitler”), pins political hope on the unknown heroism of a GI again in a photo taken from a racist mob’s attack on a black man in Detroit, adopting the victim’s voice:

The concluding line features a terse triplet of well-known American battles in the war. These “heroic” affairs pale in comparison with the struggle against racism the American GI spontaneously pursues.

Brecht focuses in on peasant-based societies to provide another defamiliarizing angle on the war. In one, a Sicilian peasant gestures dramatically in a remarkably staged image as he makes a withering comment:

The conflict’s futility and degenerate irrationality is a ongoing subject, as with the photo of a blinded Australian infantryman being escorted out of the unfamiliar terrain by a Papuan native:

Emergent solidarity, another continuing theme, and here between the soldier and the Papuan, offers a stark counterpoint to the competitive annihilation in which the global elites are engaged. The war after all takes place against the still uneven landscape of global capitalism; the Papuan brings a disconnection with imperialism’s commodity forms to the fore in his stoical distance from the battle.

A Handbook for Today

What Raymond Williams called in Brecht “that Modernist exposure of the mechanics of action” is more than style; it also signals the importance of social relations — their specific wartime modernity is traced in this epic of peasants, civilians, workers, and soldiers. Brecht weaves together these forces in defeat, defense, inhumanity, and victory. It is easy after all to lose the thread of the great epic of the subaltern classes in the tyrannical years of fascism and Stalinism. The photoepigrams have the reader searching, hunting through them. Tom Kuhn: “part of the principle is that they are all structured slightly differently, again demanding input from the reader.” As Kuhn also notes, there is an implied possibility of social intervention in many of the images. A reader on the left must now reckon with and rethink these image-poems of exile in an era of the left’s own political exile, when many have lost both workerist and anti-imperialist threads. If I have emphasized a certain historical reading of the photo-epigrams in the preceding passages, it has been out of necessity. The photo-epigrams both arrive in narrative sequence and stand on their own. Winston Churchill, appropriated from a media source, makes a salient example. His Tommy Gun-brandishing appearance marks an early section of the text:

The image identifies capitalists with gangsters (as with Arturo Ui) and criticizes the ruthless leader of a declining British Empire. Depicted as a combatant, Churchill as the “authentic” bourgeois statesman becomes vulnerable in this image, which resonates in our era of capitalist gangsters and their ruthless collaboration with far-reaching criminal syndicates. In fact, many image-poems here have a rousing character in the present, spotlighting how social circumstances have or have not changed in key respects. The idea of the contemporaneity of War Primer was the premise of the Iraq War-era’s War Primer 2, a compelling re-imaging of Brecht’s poems by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. Our post-crash era has renewed another way of seeing the photo-epigrams. Brecht looked on the war and its final settlements as one kind of end for a capitalism that had reached its limits in pre-war crisis and depression. State Socialism, however compromised, existed as an alternative for Brecht. Hitler appears late in the text again, vigorous and raging:

It is poignant to encounter this final line in an age of reaction, with its growth of far-right movements. The wily postmodern right resembles Brecht’s depictions of Hitler as they too are both cunning bourgeois politicians and the tools of the capitalist classes. For Brecht, even if fascism were vanquished, means of terrible force could be resorted to again, especially in a system without clear prospects for growth.

Weak or small oppositions from the left (movements of the squares and left electoral struggles, for example) have produced no revolutionary organizations with carapaces hard enough to make for a combative politics of anti-capitalism. Instead the womb of late capitalist social relations today churns up a powerful center with a rightward drifting political scene. Brecht, by contrast, could look to the built-out Red Army and the way it could stand in for the international proletariat (Brecht urging a post-war GDR classroom: “Never forget that men like you got hurt / So you might sit there, not the other lot. / And now don’t hide your head, and don’t desert / But learn to learn and try to learn for what”). In the middle of War Primer, its peripatetic moment, a chorus-like voice of German troops emerges:

Brecht had a complex relationship to the Soviet Union, something one can sense here: the speakers are the repelled and defeated German soldiers. He was at odds with the Socialist Realism doctrine in the arts, yet he was also a Marxist realist against the Lukacsian grain who spent the war years in California before living out the end of his life in East Germany. For Brecht, the decisive turning of the tide for the Red Army was a triumph not merely in official doctrine, but for soldiers, workers, and peasants everywhere. It is an achievement of the text to make it seem as if people — like the ones in the candid portrait of men and women’s militancy — can alter their circumstances again even now.

A dispatch from the bad old days to be read again in the bad new ones, with their meme wars among e-militias, War Primer’s proverbial form focuses history’s “narrative wisdom into a single lapidary formulation” (Jameson). In the sea of digital memes, viral images plus ironic phrases, Brecht’s poems instead serve as aide-mémoire, “punctuating ‘representation’ with ‘formulation’” (Brecht). The quatrains find a balance of contrasts in a changing cast of dramatic utterances and photos; they never merge these differences between photos into each other, nor do the poems entirely separate them. War Primer reappears then at the right moment in terms of form, as captioning currently undergoes a transformation as visual practice. It offers examples and challenges to those occupying the virtual space of contemporary media, conscripting corporate images into today’s left of the meme wars. It reminds us of the necessity of peace as much as steely organizations, militant parties, and frontal combat with the right. War Primer is unmistakably trenchant in opposition to war. Yet only in fighting in the rubble of Stalingrad, Moscow, or the bulge at Kursk, did masses of men and women deal the revolutionary right its historic defeat. In the unprecedented future that lies ahead, people like them may well be called on to do something similar again.

Works Cited

Jameson, Fredric, “Proverbs and Peasant History” and “Representability of Capitalism,” Brecht and Method (New York and London: Verso, 1998).

Kuhn, Tom, “Poetry and Photography: Mastering Reality in the Kriegsfibel,” Bertolt Brecht: A Reassessment of his Work and Legacy, ed. Robert Gillett and Godela Weiss-Sussex (Amsterdam: Rodopi 2008).

Parker, Stephen, Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

Soldovieri, Stefan, “War-Poetry, Photo(epi)grammetry: Brecht’s Kriegsfibel,” A Bertolt Reference Companion, ed. Siegfried Mews (Westport: Greenport Press, 1997)

Willet, John, “Afterword,” War Primer, Bertolt Brecht (New York and London: Verso, 2017).

David Lau is a lecturer at UC Santa Cruz. His volumes of poetry are Virgil and the Mountain Cat, Bad Opposites, and Still Dirty. His poetry and essays have appeared in New Left Review, Boston Review, Literary Hub, and Boom: a Journal of California. He is editor of Lana Turner: a Journal of Poetry and Opinion.