Broken Windows at Blue’s: A Queer History of Gentrification and Policing

On September 29, 1982, over thirty New York City police officers raided Blue’s, a bar in Manhattan’s Times Square. The following year, activist James Credle testified at congressional hearings on police misconduct, describing the brutal beatings of the Black and Latino gay men and trans people who made up the bar’s main clientele. The event galvanized lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) activists for whom police violence was a primary concern. Although one mention of a rally made it into the New York Times, Credle noted in his testimony that the incident itself had been ignored by major media outlets, an insult certainly made worse by the fact that the bar sat across the street from the Times’s own headquarters.

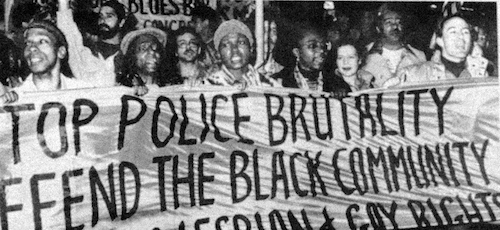

Blues Bar protest, Oct. 15, 1982. Image from Liberation News

Gay activist and journalist Arthur Bell wrote a front-page story about the raid for the alternative weekly the Village Voice. In it, he quoted Inspector John J. Martin, commanding officer of the Midtown South Precinct, who described Blue’s as “a very troublesome bar” with “a lot of undesirables” and “a place that transvestites are drawn to ... probably for narcotics use.” Bell also noted the striking contrast between the raid and another press-worthy event held that same night: a black tie dinner, $150 a plate, sponsored by the Human Rights Campaign Fund (HRCF), a gay and lesbian political action committee, at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel with a keynote by former vice president Walter Mondale.

Years earlier, Bell had written about a much more famous police raid and response, which had taken place at the Stonewall Inn bar on June 28,1969. At the time, police raids of gay bars were common, and bar owners often sought protection through payoffs to the police. On June 28, however, the Stonewall patrons and others socializing outside the bar responded to the unexpected raid with a three-day rebellion that is now credited with spurring a more militant and visible LGBT movement.

In the decade following the Stonewall uprising, police abuse remained a problem for many LGBT people, but it was joined by growing concerns about general street safety. In response, many activists attempted to convince the public that gay life was far from “undesirable” and could even be seen as a valuable asset in a city in which the discourses of crime and economic crises had become tightly intertwined. In September 1977, for example, the gay magazine Christopher Street featured a cover story titled “Can Gays Save New York City?” that included a picture of two men embracing a miniaturized image of Lower Manhattan and asked, “How many neighborhoods in Manhattan would be slums by now, had gay singles and couples not moved in and helped maintain and upgrade them?” The magazine often addressed itself to the question of how gay men were reshaping the landscape of New York, regularly featuring New Yorker–style cartoons that poked fun at gay men who were developing niche businesses or at the supposed value of gayness to new forms of industry. In another issue, the editors celebrated urban scholarship highlighting the leadership of gay men in “revitalization” efforts, describing their creativity, adaptability, ego, and openness to risk-taking as key features for achieving success in a speculation-based economy.

For many commentators, new gay investment in the central city was understood to be part of a broader process of middle-class reinvestment in urban areas — what became known as the “back-to-the-city” movement. Often called “gay gentrification,” the phenomenon of new, concentrated gay investment was debated not only by gay journalists but also by city boosters and developers, scholars, and activists, many of whom linked the rise of gay social movements with the growth of gay neighborhoods. These gay neighborhoods, they argued, provided a kind of protection for those escaping the presumed anti-gay sentiments of non-urban areas. Cast in such general terms, though, these arguments primarily described a professional class of white gay men, assumed, unlike LGBT people in general, to be free of the obligations of family, territorial, and suited to the so-called new service economy.

But as the raid on Blue’s attests, there were many other people — including many white gay men — pursuing same-sex intimacy, non-normative kinship arrangements, and gender expressions that did not conform to mainstream expectations who did not profit from restructuring real estate markets. Liberal and conservative policy makers alike condemned what they saw to be the erosion of traditional family values and gender roles as a sexual zeitgeist gone too far and among the key causes of the “social disorder” that threatened urban cores. They invoked still-popular “culture of poverty” arguments that blamed Black low-income mothers and praised new zoning restrictions that targeted public spaces and businesses in these areas. Disorder as a category would be crafted through the very strategies used to contain and curtail it, in policing philosophy as well as models of municipal governance, and in attacks on not only social uprisings but also the daily lives of those increasingly cast as a “permanent underclass.”

In fact, at the same time that gay people’s affirmative role in real estate was being praised by the mainstream and alternative press, journalists and social scientists were also publicizing theories about the need for police practice to target disorder and the “discovery” of an often amorphously defined sector of the supposedly intractable poor. In 1982, the year of the Blue’s raid, criminologists George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson introduced the ethos of “broken windows” policing to the broader public via the Atlantic magazine, and journalist Ken Auletta published The Underclass based on a series of articles from the New Yorker. Broken windows theory emphasizes the problem of disorderliness on residents’ sense of safety and in particular the effect of destabilizing, unfamiliar elements, including “loiterers,” “rowdy teenagers,” “drunks,” “prostitutes,” and the “mentally disturbed.” Similarly, Auletta explained that the contemporary underclass consisted of the “hard-core unemployed,” which he summarized in the pages of the New Yorker as “criminals, drug addicts, or pushers, alcoholics, [and] welfare mothers.”

The HRCF’s event committee for its fundraiser at the Waldorf Astoria included senators Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Edward Kennedy (who did not, however, appear in person). Unlike the politically conservative architects of broken windows theory, Moynihan and Kennedy were liberals. Yet their respective ideas about a culture of poverty and a permanent underclass were easy fits with broken windows theory, insofar as all three revolved around diagnosing cultural pathology and regulating the social norms of the poor. In these shared contexts, then, disorder functioned as a catchall for poverty in general as well as for specific forms of unregulated street life. It was also a convenient description for those seen as obstructions to the urban improvements promised by a new middle class.

Since then, gentrification has proven to be ongoing and global, and policing approaches based on broken windows theory — also known as “order maintenance” policing — have been central to the cycles of devalorization and revalorization that have reshaped New York City and cities around the world. In 1993, William J. Bratton was appointed New York City’s police commissioner for the first time. Empowered by a decade of broken windows policing in New York’s transit system (including under his own leadership), Bratton quickly crafted a city-wide police strategy of “zero tolerance” for “quality of life” infractions, escalating the enforcement and punishment of misdemeanor crimes, particularly in public spaces.

Bratton’s approach was first tested in Greenwich Village, home to the famed Stonewall riots and one of the world’s best-known gay enclaves. Among its key targets were nonresident LGBT people of color who enjoyed the neighborhood’s abundance of LGBT-oriented services and reputation as a safe haven for LGBT people. As the strategy expanded across the city, it was governed by the logic of its different spatial contexts: taking aim at homeless people and workers in the informal economy in tourist zones (such as Times Square); at unregulated street life in newly gentrified areas; and, in the form of “stop and frisk,” at Black and Latino men, especially in parts of the city devalued long enough to become new hot spots for speculative investment.

In this way, it is clear how queerness — both as an umbrella term for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identities and as a lens for examining the operation of power via normalization, stigma, and kinship regulation — offers a helpful analytic for understanding the intersection of gentrification and order maintenance policing. The celebration of gay investment alongside attacks like the one at Blue’s demonstrates the often bifurcated function of marginalized identity and social non-normativity in postwar urban development policy. Here certain lesbian and gay claims of vulnerability and calls for safety, especially those paired with or perceived as amenable to redevelopment, are celebrated at the same time that those who stand outside of white, middle-class heterosexuality (including many lesbians and gay men) continue to be targeted by police strategies that pave the way for that selective reinvestment. This framework also allows for a more complex play of identity in urban political economy more generally, refusing to substitute individual choice in the marketplace for a structural critique of capitalism or dismiss the functions of race, gender, or sexuality in ordering the city. Most important, it is an argument that has been developed by a variety of activists, then and now.

Times Square, 1982

The raid on Blue’s was violent and destructive. Bell, Credle, and other observers described the scene they encountered the next morning: blood pooled on the floor and streaked across the wall; furniture, liquor bottles, glasses, pinball machines, and mirrors smashed to fragments; and spent bullets scattered on the floor. Those present reported being beaten with nightsticks and called anti-gay and racist epithets as officers threatened to kill them and stole their money and identification. In turn, the police claimed that the raid was a response to a fight that got out of hand. Yet Bell noted in his coverage that, although the police reported that some officers had been injured, they had arrested none of the bar-goers.

Activists and journalists — mostly in the gay and leftist press — suggested that the raid had been part of an ongoing effort to “clean up” Times Square. This effort would have included Operation Crossroads, initiated by Mayor Edward Koch in 1978, which had tripled the police presence in the neighborhood and focused on “hustlers,” “prostitutes,” “drifters,” and “drug sellers.” That year, the city also passed a new zoning regulation restricting “adult physical culture” (primarily massage parlors). People familiar with the bar also pointed fingers at New York Times reporters, whom they suspected had called in complaints about patrons of Blue’s hanging out on the street.

Activist James Credle’s observation (described at this chapter’s beginning) — that the mainstream press had ignored the raid — can thus be understood as part of a broad indictment; it pointed not only to the paper’s failure to recognize the police violence experienced by the gay and trans people of color next door, but also to its literal investment in policing strategies like Operation Crossroads. Writers such as Sarah Schulman and Peg Byron explicitly named gentrification in their coverage of the incident. In fact, police efforts to “clean up” Times Square promised to raise the value not only of the Times headquarters but also, more importantly, of its biggest advertisers and, ultimately, to fuel the city growth machine. As John Logan and Harvey Molotch have shown, major city newspapers often serve as growth boosters across urban regions, advocating for development that will increase subscribers and, in turn, advertiser revenue. The New York Times has long applied this strategy.

True to form, in 1981, the paper had celebrated Times Square as undergoing a “revival,” in which the area was at last to be saved from “sin and decay” with the assistance of private funds, following an (albeit failed) Ford Foundation initiative (whose own offices were further east on 42nd Street). By the time of the Blue’s raid, the transformation of Times Square had reached a fevered pitch; no fewer than five theaters were destroyed in 1982 alone to clear the way for luxury hotel development. These projects were facilitated by popular claims about supposed new forms of disruptive, self-chosen poverty. Drawing on a colorful vocabulary and detailed descriptions, journalists and other writers generated categories of people (“bag ladies,” for example) and named them as the most difficult denizens of the broader Times Square area: “In the notorious section of midtown surrounding the Port Authority bus terminal, amid throngs of workers, transients, and tourists, lives a compact society of outsiders,” feminist Alix Kates Shulman wrote. “Hustlers, hookers, three-card monte players, con men, drug dealers, jackrollers (thieves who specialize in robbing the poor of their welfare funds) work over their marks between Times Square and the Stroll, that strip of Eighth Avenue serviced by prostitutes and pimps.”

It is thus no surprise that a policing theory targeting signs of so-called disorder would gain approval in the press, which, in turn, would help build popular consensus in support of it. While broken windows certainly had precedent in other forms of anti-poverty doctrine, racial segregation, and status-based policing, the theory would appeal to a broader political swath than the conservative criminologists who coined it. Developed out of local studies of police foot patrols, based particularly in nearby Newark, New Jersey, during the 1970s, the theory focused less on the immediate reduction of crime per se than on the perception of safety, under the assumption that certain environments cultivated future criminal opportunity. As Kelling and Wilson argued, cops working their beats, in collaboration with local residents, were best equipped to identify who belonged and who did not and to quell signs of disorder lest they lead to escalating crime.

Kelling and Wilson drew on the research of Philip Zimbardo to explain this causal relationship. In Zimbardo’s famous social psychology experiment, a run-down and seemingly abandoned car led anonymous bystanders to cause it even greater damage. Yet Kelling and Wilson interpreted abuse of the built environment narrowly: quality-of-life policing should target graffiti, per their theory, but not surrounding buildings dilapidated due to landlord neglect. The majority of the theory’s examples of disorder, moreover, are not physical but manifest instead in the status and practices of marginalized individuals, who are then considered eligible for arrest.

The emphasis on the primacy of an individual’s sense of safety or fear, the proposed solution of citizen-police collaboration, and the idea that signs of disorder might lead to bigger threats were, at the time, not only tenets of conservatism but consistent as well with the approach to inequality adopted by postwar liberal politics. The influence of social psychology and faith in the power of rational choice as well as the idea that liberal politics could coexist easily with greater police power bolstered rather than loosened the relationship between the police and the new middle-class communities moving into central city regions abandoned by capital years before. In the case of the new lesbian and gay movement, the social liberalism that celebrated sexual freedom would be understood by some to support place-based land claims, an argument that required separating the terms of sexual/kinship non-normativity from lesbian and gay identity formation. Moreover, gay and lesbian activists held a newly formed belief that individualized, violent threat might be made manifest and promised by the representational signs of the city.

Safe in the City

Prior to the late 1960s and early 1970s, the idea of a gay neighborhood as it is commonly held today did not exist, and LGBT people were most associated with areas that housed a range of other social outsiders — such as artists and bohemians, drug users, sex workers, and those made itinerant due to poverty, often in areas considered to be vice districts or skid rows. The risk of street violence was rarely understood as shared by all gay people; instead, police abuse stood at the fore, and activists — in some cases associated with War on Poverty programs — tied the problem of policing to street cleanups intended to facilitate new development.

They also fought criminalization and stigma, drawing, as historian Christopher Agee has shown, on the concept of the “harm principle” (arguing that acts that hurt no one should not be considered crimes) and fighting status-based anti-vagrancy laws, both of which disproportionately targeted homosexuals. And, like many participants in the Great Society, they drew on liberal psychology to emphasize the healthiness of prideful identification and increasingly framed “gay” as an affirmative identity rather than simply a stigmatized practice. But in the process of distinguishing homosexuality from categories of harm — those labeled as criminal, sick, or causing psychic damage — the racial and economic associations of those other stigmatized practices were left intact.

By the start of the 1970s, popular acceptance of homosexuality had grown, and realtors began marketing gay people as the ideal tenants of changing neighborhoods, focusing especially on middle-class white gay men as high-earning, risk-taking, and family-free. But, in an important distinction, the celebration of renters and owners did not include those whose displays of queerness primarily took the form of public intimacy, gender non-conformity, or participation in street-based economies. As one journalist explained in late 1969, vice districts that were associated with public and commercial sex, such as Times Square, were not considered to be gay neighborhoods since their “gay legions are transient rather than permanent.”

Gay neighborhoods emerged alongside a growing movement that had inherited from earlier activism commitments to fighting police abuse and arguing that homosexuality be designated as neither a crime nor an illness. But as the decade continued, vulnerability to violence as a general category was increasingly cast as a unifying gay experience writ large. In turn, on the streets, activism manifested increasingly in campaigns for self-protection (such as safe-streets patrols) that blurred the terms of gay community cohesion and crime control. In other words, in arguing that they were not criminals or safe from harm, many gay men and lesbians — in particular those who benefited from the protection of whiteness or class status — aligned themselves with dominant narratives about those who were. These assumptions shaped their sense of who did and did not belong in gay neighborhoods: the same determination at the core of Kelling and Wilson’s own solution.

And with time, these suppositions achieved the status of common knowledge. Aligned with the popular uptake of urban research — including public familiarity with theories of, for example, the culture of poverty, Black rage, and rational choice criminology — white gay activists turned to cooperative and crime of opportunity policing rather than anti-poverty solutions, deeming the latter impossible to realize. Even the very concept of homophobia would be ascribed to a uniform culture of racialized poverty. Moynihan’s use of the culture of poverty thesis described a Black propensity for violence and attributed it to inequality and emasculation resulting from female-headed households. At the same time, definitions of homophobia outlined a vulnerable masculinity that might take expression in violent behavior. Considered together, Black poverty — rather than the structural constraints upholding the ideals of the normative nuclear family or procreative sex — was seen as a risk to gay identity, which thus functioned, by default, as white, male, and middle-class, even as activists sought to expand the category of gay identity beyond these lines. As a result, the fight against crime was often expressed as a fight against homophobia, itself increasingly understood as the expression of disorder associated with those most targeted by police policy dedicated to normalization and control. And, borrowing from the feminist anti-rape movement, activists often found danger in the signs of potential threat — whether in the embodiment of those who seemed to be outsiders or in line with the race and class terms of a “homophobic” diagnosis — which aligned with a broken windows–style fixation on the outsider rather than the violent act itself.

By the end of the 1970s, gay activists were leaders in community-partnership policing models. While some were certainly influenced by the broad law-and-order politics set into motion by Richard Nixon and other conservative politicians of the era, mainstream lesbian and gay ideas of urban crime, safety, and the role of the police continued to borrow from liberal visions. These included the ongoing influence of racialized ideas of psychological injury and the values of self-help from the War on Poverty and other liberal programs of the period, but also from new municipal police policies. The growth of national gay anti-violence politics was anchored in anti-crime models based in New York and San Francisco. As Agee has shown, the emergence of a cosmopolitan liberalism in San Francisco merged the ethos of inclusiveness with a hard-nosed fight against crime. This followed the development of empirically oriented managerial growth politics: the eventual strategies adopted would privilege the localist visions of a professional class that supported stronger police discretion as part of community-based policing — the cornerstone of broken windows theory’s participatory, collaborative solutions.

As gay safety activism moved onto a national stage, activists sought partnership with other national — and even international — efforts dedicated to fighting crime. The crime victims' rights movement, for example, had gained prominence in the early 1980s and, along with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) of B’nai B’rith, become leaders in the fight for hate crime statutes (which further penalize crimes found to be motivated by bias). LGBT activists found common ground with the ADL’s fight against religious persecution, arguing that lesbians and gay men shared the experience of non-visible marginalized identities and that threats to both groups often manifested in attacks on the built environment or within neighborhoods that represented those targeted.

It is also worth noting that among the ADL’s leading projects during this period were campaigns combating US student activism against Zionism and supporting US–Israeli police training exchanges. The latter efforts were facilitated by the ADL’s affiliated William and Naomi Gorowitz Institute on Terrorism and Extremism. In 2010 the Gorowitz Institute honored William Bratton, noting the connection between his early training in hate crime policy in Boston and his later implementation of broken windows policing in New York. As mentioned above, broken windows theory first formalized in New York quality-of-life policing in the gay enclave of the West Village. Both gay and straight residents collaborated with one of the policy’s biggest advocates—the Guardian Angels, a controversial anti-crime vigilante group supported by then New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani — as they targeted loitering, noise, drugs, sex work, and gangs, and took aim at LGBT youth and trans women of color.

“Gay, Straight, Black, White, All United to Fight the Right!”

The activists who mobilized on behalf of Blue’s represented a broad range of organizations. This included members of Black and White Men Together (BWMT), Dykes Against Racism Everywhere (DARE), the Coalition against Racism, Anti-Semitism, Sexism, and Heterosexism (CRASH), Salsa Soul Sisters, All-People’s Congress, Harlem Metropolitan Community Church, Third World Lesbian and Gay Alliance, El Comité Homosexual Latinamericano, Lavender Left, and the New York Prostitutes Collective (which was associated with both Black Women for Wages for Housework and Wages Due Lesbians), among others. Many of these groups also joined the newly founded Coalition Against Police Repression. The raid in late September 1982 was followed by another police raid in early October, considered by activists to be retaliation by the police for the attention they had garnered. With momentum continuing to build, over 1,100 people turned out to the organizers’ biggest protest, on October 15, 1982. The issue was covered by the gay press nationwide, and San Francisco activists even held a solidarity rally.

The focus of the protests was twofold: most immediately, activists sought to link the attack on Blue’s to other challenges to gay and lesbian bars in the city as well as to new patterns of gentrification and policing. They highlighted, for example, how lesbian bars had been targeted for removal by the city’s administrative strategies; both the Duchess and Déjà Vu, the latter of which had a large lesbian of color clientele, had been denied liquor licenses despite a lack of official complaints. Activists also protested police sweeps that profiled trans women of color for suspected prostitution in Greenwich Village, especially near the piers at the end of historic Christopher Street and up the West Side to the meatpacking district. They connected the attacks on gay bars and trans women with the denial of public housing to nontraditional family units, the enforcement of rigid anti-immigration laws, and the criminalization of prostitution, all of which were understood to be part and parcel of the gentrification of the city more generally.

Activists’ second focus was to tie these issues to the risks of an ascendant Right on a local and national scale. They named the threat of Ronald Reagan’s proposed Family Protection Act, arguing that the ideal of the normative family was linked to efforts to “clean up” places like Times Square. And many activists, especially those associated with Left/ socialist political parties, put the blame for the attack on Blue’s squarely on newly elected mayor Edward Koch. Although a Democrat, Koch won the election with promises to use law-and-order and austerity tactics to facilitate the transformation of places such as Times Square. Like Reagan, his supposedly charismatic charm and populist appeal was part of the rise of neoliberal centrist coalitions in the early 1980s. In 1981, Koch praised Reagan at a press conference at the Waldorf Astoria, aligning himself against Jimmy Carter with his position on Israel and calling Reagan a “man of character.” In exchange, the White House approvingly acknowledged Koch’s lack of a strong opposition to massive federal cuts to city services.

In later years, Koch would occupy a contradictory place in the political estimations of the gay community: he was unforgivably slow to respond to AIDS but was also an active public supporter of anti-discrimination legislation. In this context, the attack on Blue’s and the political response to it presented an opportunity to mobilize those lesbians and gay men who had become complacent about the issues affecting the most marginalized LGBT people, their distance from these issues well represented by the Mondale-headlined fundraiser. Activists emphasized that the attack on Blue’s was more violent than the Stonewall raid had been, and that the targets of gentrification and policing who were not always LGBT-identified — such as sex workers, homeless people, and drug users — should also be included in LGBT political coalitions. Their approach contrasted with that of more mainstream gay organizations, who responded to the rise of the Right with solutions to reported heightening of street violence based in self-protection and “crime awareness.”

In the early 1980s, activists across the country adopted and refuted the merged terms of gay protection and gentrification. In San Francisco, Lesbians Against Police Violence (LAPV) staged a skit about the interaction of lesbian vulnerability, policing, and neighborhood transformation. Titled “Count the Contradictions,” it was organized as a sequence of scenes in a gentrifying neighborhood in which the realization of opportunity for some foreclosed it for others: white lesbians calling for police protection from random street harassment that increased violence against working-class Latino men; multiple-adult lesbian households outpricing single mothers; gay men’s desires for an affirmative, visible identity manifesting in private property; and gay developers’ claims of group identity excluding gay men without the ability to afford the rent. LAPV members performed on street corners and hosted discussions and reading groups that explored changing policing strategies in the context of capitalist development, locating the vexed terms of safety as the key ground for debate.

Years later, the formalization of quality-of-life policing in New York and its application in laws such as “sit/lie” ordinances (which prohibit sitting or lying down in public spaces) in San Francisco and other California cities would also meet creative responses from social movements. In Greenwich Village, for example, where Bratton’s new policy affected LGBT youth of color most directly, activists from groups such as Fabulous Independent Educated Radicals for Community Empowerment (FIERCE) fought quality-of-life policing in an attempt to stall the hyper-development of a long-gentrified area. Among their most innovative tactics were protests in which demonstrators simply enacted prohibited acts: eating or playing cards while seated on street corners, drawing graffiti (on disposable objects), listening to music and having fun. Activists also participated in community meetings, despite official regulations stipulating that only those with residential — as opposed to use — claims on the neighborhood could participate.

Conclusion

For decades, those who have engaged in critical debate about gentrification instead of celebrating the process as a natural achievement of the market have been divided into two main camps: those who emphasize the significance of individual consumer choice and those who highlight the global dynamics of uneven economic development. Examining the role of gay men as motors of gentrification has been a key way to explore moral imperatives within a consumer landscape; this has also been the case in discussions of artists and others seen as occupying ambiguous class positions in the urban context. But as Neil Smith once argued, it was capital moving “back to the city” rather than the origins or preferences of individual new residents that most determined people’s claims to place.

In this way, LGBT populations should not be understood as the vanguard of gentrification or as uniquely vulnerable to the violence of policing. Such arguments restrict themselves to the framework of consumer choice and distill police violence as motivated by individual responses to singular categories of alterity. These assumptions are central to liberal critiques of gentrification and policing that maintain both as open to remediation. Rather, the correlation between gay identity and gentrification is most secured by those who capitalize on what they claim to be essential characteristics or conditions that are celebrated by the market. To repeat, mainstream gay political claims in the city emerged by expanding the distance — conceptual and spatial — between affirmative gay identity and the broad matrix of so-called deviances often associated with racialized poverty. This was facilitated by the claim that policing should focus on behavior (such as loitering) rather than status (such as homosexual). But that strategy did little to assist those who remained locked within the stronghold of criminalization’s categorizations, releasing some without challenging one of their greater purposes — namely, to prime the city for private investment.

Here gay identity functions in opposition to disorder; the people marked for dispossession in the new economy may be targeted in the name of “gay safety.” This is the material of quality-of-life policing: Kelling and Wilson’s treatise is in many ways a rejection of the separation of status from behavior. As Allen Feldman writes, “Arrest is the political art of individualizing disorder.” These ideas are also in line with social science research and policy that treats poverty as a pathology that harms not only the individual but neighborhoods as well, justifying “cleanups” that provide pro ts to owners rather than resources to residents. Such research and policies underscore the central role liberal psychology has played in neoliberal policing that individualizes ideas of harm and protection. Today the idea of “safe space” so common in classroom and social service contexts can sometimes be, like broken windows theory, more about the perception of safety than anything else.

This analysis of the relationship between policing and gentrification has also been elaborated by activists such as James Credle, with whom I opened this essay and who was a member of Black and White Men Together (BWMT; later, Men of All Colors Together) in the 1980s. In general, radical anti-gentrification groups such as BWMT, DARE, LAPV, and CRASH fought gay participation in gentrification less by targeting individual consumer choice — DARE, for example, recognized the benefits of pooled resources among lesbians while warning against those who would capitalize on that shared identity for profit — and more by dedicating themselves to organizing around issues like policing (such as the raid on Blue’s) that facilitated gentrification on the ground.

This multi-issue and multi-scale tactic currently characterizes a new generation of activism against order maintenance policing as it has taken form in policies across the United States and the world: whether in heightened ticketing in Ferguson, Missouri; stop and frisk in New York and Baltimore; or police–community partnerships in Chicago and Milwaukee. Political scientist Cathy Cohen recently described some of this activism — notably led by Black youth, and that she groups as part of a broad “black lives movement” — as among the most interesting examples of radical queer politics today. Her contention is based not only on the significant proportion of LGBT and queer-identified people in the movement’s leadership, but also on the focus of these campaigns on how such policies seek to normalize and discipline kinship, gender, and everyday pleasures in ways inclusive of but not reducible to LGBT identity alone.

In many of these campaigns in recent years, activists have shown how the regulation of behavior deemed to be non-normative can be tightly entwined with real estate interests. For example, in Milwaukee, Dontre Hamilton was shot to death by a police officer who had responded to a call from Starbucks workers who had supposedly followed company protocol and reported Hamilton’s behavior as making them feel uncomfortable. Hamilton had been sleeping in Red Arrow Park, and the placement of the café there is an example of the kind of public–private partnerships that Wisconsin governor Scott Walker had so prized when he was Milwaukee County executive. In New York City, police killed Akai Gurley in a stairwell of the Louis H. Pink Houses in East New York, one of Brooklyn’s poorest neighborhoods and currently the site of rampant real estate speculation. The police cited the dangerous reputation of the complex, but little if any responsibility was assumed by the New York City Housing Authority, which failed to provide sufficient lighting in its stairwells. And Eric Garner was killed by police in New York after suspicion of selling “loosies” (single cigarettes) — exactly the type of minor violation targeted by quality-of-life laws.

In all of these cases, radical LGBT and queer activists were among those who organized in response, and they countered the claims of mainstream LGBT organizations that prioritize inclusion in the status quo over broad social and economic transformation. In the words of Cara Page of the Audre Lorde Project and Krystal Portalatin of FIERCE, the real threats are not those individuals whose lives are considered to be at a distance from dominant “norms,” but rather:

when banks are allowed to engage in predatory practices that target communities of color and force groups to remain in poverty; when Detroit can declare bankruptcy on a city of mostly black communities and then take away basic rights such as water; when corporations are allowed to abuse other countries and depress US economies; when the US military continues to back and support Israel’s oppression of Palestinian people and land.

In this way, activists continue to draw the connections between local and global acts of policing and dispossession, while tracing how the construction of social norms — and how they are made legible through the interplay of, in particular, race, gender, and sexuality — are central to this process. And, finally, they show how the promises of solidarity offer much more than those of safety, and provide a collective alternative to solutions defined within rather than against the market.

This essay is taken from Policing the Planet: Why The Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter, edited by Jordan T. Camp and Christina Heatherton.

Christina B. Hanhardt is an associate professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is the author of the book Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence (Duke, 2013).